BANQUETING IN ANCIENT ROME

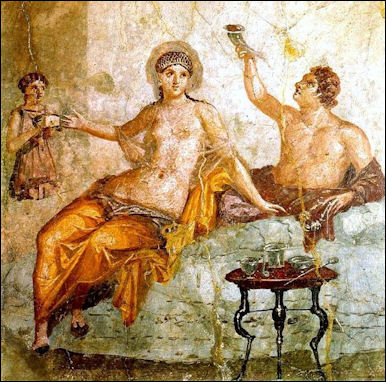

Herculaneum fresco of a banquet Silvia Marchetti of CNN wrote: Members of the Roman upper classes regularly indulged in lavish, hours-long feasts that served to broadcast their wealth and status in ways that eclipse our notions of a resplendent meal. “Eating was the supreme act of civilisation and celebration of life,” said Alberto Jori, professor of ancient philosophy at the University of Ferrara in Italy. [Source: Silvia Marchetti, CNN, December 25, 2023]

Katharine Raff of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The festive consumption of food and drink was an important social ritual in the Roman world. Known in general terms as the convivium (Latin: "living together"), or banquet, the Romans also distinguished between specific types of gatherings, such as the epulum (public feast), the cena (dinner, normally eaten in the mid-afternoon), and the comissatio (drinking party). Public banquets, such as the civic feasts offered for all of the inhabitants of a city, often accommodated large numbers of diners. In contrast, the dinner parties that took place in residences were more private affairs in which the host entertained a small group of family friends, business associates, and clients. “ Roman literary sources describe elite private banquets as a kind of feast for the senses, during which the host strove to impress his guests with extravagant fare, luxurious tableware, and diverse forms of entertainment, all of which were enjoyed in a lavishly adorned setting. [Source: Katharine Raff, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org]

The historian William Stearns Davis wrote:“The Romans laid a vast stress upon the joys of eating. Probably never before or since has greater effort been expended upon gratifying the palate. The art of cooking was placed almost on a level with that of sculpture or of music. It is worth noticing that the ancient epicures were, however, handicapped by the absence of most forms of modern ices, and of sugar. The menu here presented was for a feast given by Mucius Lentulus Niger, when, in 63 B.C., he became a pontifex. There were present the other pontifices including Julius Caesar, the Vestal Virgins, and some other priests, also ladies related to them. While this banquet took place under the Republic, it was probably surpassed by many in Imperial times.

Giorgio Franchetti, a food historian and scholar of ancient Roman history, and “archaeo-cook” Cristina Conte. have tracked down ancient recipes and records on banqueting. They wrote “Dining With the Ancient Romans,” and organize dining experiences at archaeological sites in Italy that give guests a taste of what eating at a Roman banquet is like.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome” by Patrick Faas and Shaun Whiteside (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Satyricon” (Penguin Classics) by Petronius (Gaius Petronius Arbiter Amazon.com

“Dining Posture in Ancient Rome: Bodies, Values, and Status” by Matthew B. Roller Amazon.com;

“A Taste of Ancient Rome” by Ilaria Gozzini Giacosa, Anna Herklotz (1992) Amazon.com

“The Routledge Handbook of Diet and Nutrition in the Roman World” by Paul Erdkamp and Claire Holleran (2018) Amazon.com;

“Galen on Food and Diet” by Mark Grant (2002) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Cookery Book: A Critical Translation of the Art of Cooking, for Use in the Study and the Kitchen” by Elisabeth Rosenbaum (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Roman Cooking: Ingredients, Recipes, Sources” by Marco Gavio de Rubeis (2020) Amazon.com;

“Tasting Rome: Fresh Flavors and Forgotten Recipes from an Ancient City: A Cookbook”

by Katie Parla and Kristina Gill (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Cuisine and Food Culture in Ancient Rome” by Rowan J Trhymden (2025) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Rome Olive Guide: Olive Trees, Fruit, Oil & Recipes” by Pliny, Columella, et al. | (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Cookbook from Ancient Rome: Classic Recipes Reimagined for Today” by Lily Heritage (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Classical Cookbook” by Andrew Dalby and Sally Grainger (2012) Amazon.com;

“Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome: An Exploration of Culinary History in an Ancient Roman Cookbook” by Apicius, translated by Joseph Dommers Vehling (2023) Amazon.com;

“In Ancient Rome (Food and Feasts)” by Philip Steele (1994) Amazon.com;

“Food in Roman Britain” by Joan P. Alcock (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Resilience of the Roman Empire: Regional Case Studies on the Relationship Between Population and Food Resources” by Dimitri Van Limbergen, Sadi Maréchal, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Food Provisions for Ancient Rome: A Supply Chain Approach” by Paul James (2020) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis”

by Peter Garnsey (1988) Amazon.com;

“Brill’s Companion to Diet and Logistics in Greek and Roman Warfare (Brill's Companions to Classical Studies: Warfare in the Ancient Mediterranean World”

by John F. Donahue and Lee L. Brice (2023) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Great Success: Sustaining the Roman Army on Campaign” by Alexander Merrow , Agostino von Hassell, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Intoxication in the Ancient Greek and Roman World” by Alan Sumler (2023) Amazon.com;

Paintings and Archaeological Evidence of Roman Banquets

Archaeological evidence of Roman housing has shed important light on the contexts in which private banquets occurred and the types of objects employed during such gatherings. Paintings from Pompeii show banqueting scenes. From the attention that banquets and dinner-parties get in written texts is presumed they were importants parts of Roman life. Dr Joanne Berry wrote for the BBC: “ Guests reclined on couches padded with cushions and draperies and were served food and drinks by slaves (usually depicted as smaller in scale, to suggest their status, in paintings). [Source: Dr Joanne Berry, Pompeii Images, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]|

“Examples of wooden couches have been found in several of the excavated houses of Pompeii, and there are also many masonry couches in the gardens, for use when dining outside. Dinner-parties could be an opportunity for the rich elite to display their wealth, for example by providing entertainment in the form of dancers, acrobats and singers or by using an expensive dinner service.” In one Pompeii wall-painting, “a slave holds out a drinking cup to one of the diners. Occasional silver services, such as the famous vessels discovered in the House of Menander, have been excavated at Pompeii, but in general most vessels that might have been used for dining were made from bronze and glass.”

In June 2018, archaeologists discovered a painted tomb in excellent condition from the 2nd century B.C. with images of a banquet with exceptionally executed figures in Cumae in the region of Naples, Priscilla Munzi, CNRS researcher at the Jean Bérard Center (CNRS-EFR), and Jean-Pierre Brun, professor at the Collège de France, are overseeing the excavations of a Roman-era necropolis there. Popular Archaeology reported: A naked servant carrying a jug of wine and a vase is still visible; the banquet’s guests are thought to have been painted on the side walls. Other elements of the banquet can also be distinguished. In addition to the excellent state of conservation of the remaining plaster and pigments, such a décor in a tomb built in that period is rare; its “unfashionable” subject matter was in vogue one or two centuries earlier. This discovery is also an opportunity to trace artistic activity over time at the site. [Source Popular Archaeology, September 25, 2018]

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

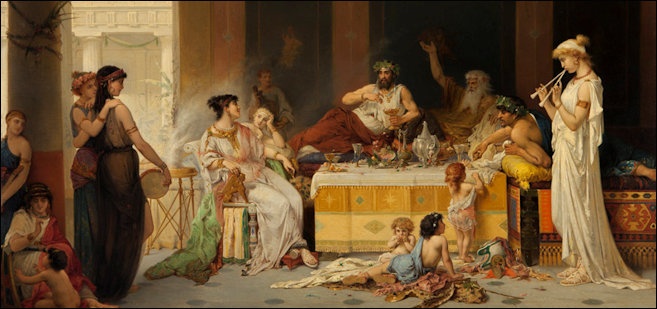

Elaborate Banquet in Ancient Rome

Banquet in Nero's palace

Roman banquets sometimes lasted for ten hours. They were held in dining rooms decorated with frescos of Helen of Troy and Castor and Pollox. Slaves cooked the meal and beautiful women served the dishes. Prostitutes, jugglers, musicians, acrobats, actors and fire-eaters entertained guests between courses. Masseuses washed their feet with perfumed water.

Banquets were regarded as demonstrations of wealth and position. Spending the equivalent of thousands of dollars was not uncommon. Feasting was so popular that satires were written about it and laws were passed outlawing the consumption of particularly rare delicacies and hosting especially large banquets. Police had stake-outs set up in the markets to prevent extravagant purchases. Menus had to be approved by local officials. In some places dining rooms were required to have windows so inspectors could check the proceedings

Describing a lavish feast, Petronius wrote in Satyricon: “Spread around a circular tray were the twelve signs of the Zodiac, and over each sign the chef had put the most suitable food, Thus, over the sign of Aries were chickpeas, over Taurus a slice of beef, a pair of testicles and kidneys over Gemini, a wreath of flowers over Cancer, over Leo an African fig, virgin sowbelly on Virgo, over Libra a pair of scales with tartlet in one pan and cheesecake in the other, over Scorpio a crawfish, a lobster on Capricorn, on Aquarius a goose, and two mullets over Pisces. The centerpiece was a clod of turf with grass still green surmounted by a fat honeycomb. With some reluctance we began attacking this wretched fare." Petronius slit his own throat and bled to death while eating a feast with friends.

Pliny described the gourmet Marcus Gabius Apicus as "the greatest spendthrift of all." He said he squandered most of his large fortune on feasts and then, anticipating a need to economize, committed suicide with poison. In A.D. 20 Apicus hosted a legendary banquet that cost between 60 million and 100 million sesterces ($15 million). There is no record of what was eaten but he was left with only 10 million sesterces afterwards. It was after this feast that he committed suicide. According to a 16th century manuscript: "Six hundred thousand spent, and but/ Ten thousand left to feed his gutt." Fearing for want of food and dye," Despairing, he did poyson buy:/ Never was known such gluttonye."

Elagabulus and the Banquets of Rome’s Filthy Rich

Little need be said of the banquets of the vulgar nobles in the last century of the Republic and of the rich parvenus who thronged the courts of the earlier emperors. They were arranged on the same plan as the dinners we have described, differing from them only in the ostentatious display of furniture, plate, and food. So far as particulars have reached us they were, judged by the canons of today, grotesque and revolting rather than magnificent. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

re-enacting a Roman banquet

“Couches made of silver, wine instead of water for the hands, twenty-two courses to a single cena, seven thousand birds served at another, a dish of livers of fish, tongues of flamingoes, brains of peacocks and pheasants mixed up together, strike us as vulgarity run mad. The sums spent upon these feasts do not seem so fabulous now as they did then. Every season in our great capitals sees social functions that surpass the feasts of Lucullus in cost as far as they do in taste and refinement. As signs of the times, however, as indications of changed ideals, of degeneracy and decay, they deserved the notice that the Roman historians and satirists gave them.

The teenage emperor Elagabulus hosted a famous feast which featured camels’ feet, honeyed dormice, the brains of 600 ostriches, conger eels fattened on Christian slaves, and caviar from fish caught by the emperor's private fishing fleet. Guests were also given a dish with a sauce made by a chef who had to eat nothing but that sauce if the emperor didn't like it.

Elagabulus reportedly came to the banquet on a chariot pulled by naked women and is said to have liked to mix gold and pearls with peas and rice. He ate and drank from bejeweled gold plates and goblets. Guests at his banquets were given free slaves and homes and live versions of the animals they had just eaten. His idea of a practical joke was to play a game and give the winner a prize of dead flies, or to drug guests’ wine and have them wake in a room filled with lions and leopards. These excesses exhausted Rome's treasury and Elagabulus soon met his end, assassinated in a latrine.

Food and Wine at an Elaborate Roman Banquet

Silvia Marchetti of CNN wrote: Game meat such as venison, wild boar, rabbit and pheasant along with seafood like raw oysters, shellfish and lobster were just some of the pricey foods that made regular appearances at the Roman banquet. What’s more, hosts played a game of one-upmanship by serving over-the-top, exotic dishes like parrot tongue stew and stuffed dormouse. “Dormouse was a delicacy that farmers fattened up for months inside pots and then sold at markets,” Jori said. “While huge quantities of parrots were killed to have enough tongues to make fricassee.” [Source: Silvia Marchetti, CNN, December 25, 2023]

Among the unusual recipes prepared by Conte is salsum sine salso, invented by the famed Roman gourmand Marcus Gavius Apicius. It was an “eating joke” made to amaze and fool guests. The fish would be presented with head and tail, but the inside was stuffed with cow liver. Clever sleight of hand, combined with shock factor, counted for a lot in these competitive displays. Wine wasn’t always drunk straight but spiked with other ingredients. Water was used to dilute the alcohol potency and allow revelers to drink more, while seawater was added so that the salt preserved wine barrels coming from faraway corners of the empire. “Even tar was a common substance mixed with the wine, which over time blended with the alcohol. The Romans could hardly taste the nasty flavour,” Jori said.

Katharine Raff of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “A proper Roman dinner included three courses: the hors d'oeuvres (gustatio), the main course (mensae primae), and the dessert (mensae secundae). The food and drink that was served was intended not only to satiate the guests but also to add an element of spectacle to the meal. Exotic produce, particularly those from wild animals, birds, and fish, were favored at elite dinner parties because of their rarity, difficulty of procurement, and consequent high cost, which reflected the host's affluence. Popular but costly fare included pheasant, thrush (or other songbirds), raw oysters, lobster, shellfish, venison, wild boar, and peacock. Foods that were forbidden by sumptuary laws, such as fattened fowl and sow's udders, were flagrantly consumed at the most exclusive feasts. In addition, elaborate recipes were invented—a surviving literary work, known as Apicius, is a late Roman compilation of cookery recipes. These often required not only expensive ingredients and means of preparation but also elaborate, even dramatic, forms of presentation. [Source: Katharine Raff, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

“At the Roman banquet, wine was served throughout the meal as an accompaniment to the food. This practice contrasted with that of the Greek deipnon, or main meal, which focused on the consumption of food; wine was reserved for the symposium that followed. Like the Greeks, the Romans mixed their wine with water prior to drinking. The mixing of hot water, which was heated using special boilers known as authepsae, seems to have been a specifically Roman custom. Such devices (similar to later samovars) are depicted in Roman paintings and mosaics, and some examples have been found in archaeological contexts in different parts of the Roman empire. Cold water and, more rarely, ice or snow were also used for mixing. Typically, the wine was mixed to the guest's taste and in his own cup, unlike the Greek practice of communal mixing for the entire party in a large krater (mixing bowl). Wine was poured into the drinking cup with a simpulum (ladle), which allowed the server to measure out a specific quantity of wine.” \^/

Describing the Bill of Fare of a Great Roman Banquetin 63 B.C. Macrobius wrote in Saturnalia Convivia, III.13: “Before the dinner proper came sea hedgehogs; fresh oysters, as many as the guests wished; large mussels; sphondyli; field fares with asparagus; fattened fowls; oyster and mussel pasties; black and white sea acorns; sphondyli again; glycimarides; sea nettles; becaficoes; roe ribs; boar's ribs; fowls dressed with flour; becaficoes; purple shellfish of two sorts. The dinner itself consisted of sows' udder; boar's head; fish-pasties; boar-pasties; ducks; boiled teals; hares; roasted fowls; starch pastry; Pontic pastry.” [Source: Macrobius, “Saturnalia Convivia, III.13:” The Bill of Fare of a Great Roman Banquet, 63 B.C., William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

Roses of Heliogabalus (Elagabulus)

Roman Banquet Tableware and Vessels

Katharine Raff of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “A decadent meal required an elaborate table service comprising numerous vessels and utensils that were designed to serve both functional and decorative purposes. The most ostentatious tableware was made of costly materials, such as silver, gold, bronze, or semi-precious stone (such as rock crystal, agate, and onyx). However, even a family of moderate means likely would have owned a set of table silver, known as a ministerium. Major collections of silver tableware, such as those found at Pompeii, Moregine (a site on the outskirts of Pompeii), Boscoreale, and Tivoli, reflect the diversity in the shapes and sizes of vessels and utensils used. [Source: Katharine Raff, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

“A complete table service included silver for eating (argentum escarium) and silver for drinking (argentum potorium). Silver for food included large serving trays and dishes, and individual bowls and plates, as well as spoons, which were the primary eating utensil used by the Romans. The spoon came in two popular forms: the cochlear, which has a small, circular bowl and a pointed handle that was used for eating shellfish, eggs, and snails; and the ligula, which has a larger, pear-shaped bowl. Knives and forks were less commonly used, although examples have survived. Among the drinking silver, cups came in a variety of forms, the most popular of which had their origins in Greek types, such the scyphos and the cantharus, both of which are two-handled drinking cups. In numerous cases, silver drinking cups have been found in pairs. It is possible that they were intended for use in convivial rituals, such as the drinking of toasts. \^/

“The most ornate silver cups were decorated with reliefs in repoussé, which frequently depict naturalistic floral and vegetal motifs, animals, erotic scenes, and mythological subjects. Imagery associated with Dionysos, the Greek god of wine, intoxication, and revelry, was popularly used on objects designed for serving and imbibing wine. This pair of cups, both of which depict cupids dancing and playing instruments, would have been especially suitable for a drinking party because their subject matter evoked the rites of Dionysos. Dionysiac imagery was also employed in other banqueting accoutrements, such as a bronze handle attachment for a situla (bucket-shaped vessel) in the form of a mask of a satyr or Silenos. \^/

“Similar types of tableware were made of less costly materials, yet they exhibit a high level of craftsmanship. Glass had become especially fashionable and was more readily available in the Roman world following the rapid development of the Roman glass industry in the first half of the first century A.D.. New techniques allowed glassmakers to create vessels in a variety of styles, such as monochrome glass, polychrome mosaic glass, gold-band glass, and colorless glass, which mimicked the appearance of costly rock crystal vessels. Cameo glass, which was made by carving designs into layered glass, was especially prized among the elite for its delicately carved imagery, which was similar to that found on silver and gold tableware. \^/

Roman banquet

“Vessels made of terracotta were another affordable alternative. Terra sigillata, a type of mold-made pottery known for its lacquerlike red glaze, was widely popular. Terra sigillata vessels from Arretium (modern Arezzo, Italy), known as Arretine ware, were renowned for their relief decoration, which was typically produced using stamps of different figures and motifs. The terra sigillata industry also flourished in the provinces, particularly in Gaul, where plain and decorated vessels were mass-produced and exported to diverse parts of the empire.” \^/

Roman Banquet Dining Room and Entertainment

Katharine Raff of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The dining room was one of the most important reception spaces of the residence and, as such, it included high-quality decorative fixtures, such as floor mosaics, wall paintings, and stucco reliefs, as well as portable luxury objects, such as artworks (particularly sculptures) and furniture. Like the Greeks, the Romans reclined on couches while banqueting, although in the Roman context respectable women were permitted to join men in reclining. This practice set the convivium apart from the Greek symposium, or male aristocratic drinking party, at which female attendees were restricted to entertainers such as flute-girls and dancers as well as courtesans (heterae). [Source: Katharine Raff, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

"A dining room typically held three broad couches, each of which seated three individuals, thus allowing for a total of nine guests. This type of room is commonly described as a triclinium (literally, "three-couch room"), although dining rooms that could accommodate greater numbers of couches are archaeologically attested. In a triclinium, the couches were arranged along three walls of the room in a U-shape, at the center of which was placed a single table that was accessible to all of the diners. Couches were frequently made of wood, but there were also more opulent versions with fittings made of costly materials, such as ivory and bronze. \^/

“The final component of the banquet was its entertainment, which was designed to delight both the eye and ear. Musical performances often involved the flute, the water-organ, and the lyre, as well as choral works. Active forms of entertainment could include troupes of acrobats, dancing girls, gladiatorial fights, mime, pantomime, and even trained animals, such as lions and leopards. There were also more reserved options, such as recitations of poetry (particularly the new Roman epic, Virgil's Aeneid), histories, and dramatic performances. Even the staff and slaves of the house were incorporated into the entertainment: singing cooks performed as they served guests, while young, attractive, and well-groomed male wine waiters provided an additional form of visual distraction. In sum, the Roman banquet was not merely a meal but rather a calculated spectacle of display that was intended to demonstrate the host's wealth, status, and sophistication to his guests, preferably outdoing at the same time the lavish banquets of his elite friends and colleagues.” \^/

glass from Pompeii

Many banquets lasted eight or ten hours. They were divided into acts, as it were: in the interval after the entrees a concert was accompanied by the gesticulations of a silver skeleton; after one roast there was an acrobatic turn and Fortunata danced the cordex; before dessert there were riddles, a lottery, and a surprise when the ceiling opened to let down an immense hoop to which little flasks of perfume were attached for immediate distribution. It was very generally felt that no dinner party was complete without the buffooneries of clowns, antic tricks of wantons around the tables, or lascivious dances to the clatter of castanets, for which Spanish maidens were as renowned in Rome as are the Aulad Nail among the Arabs of Algeria today. Pliny the Younger found nothing amusing in such entertainments: "I confess I admit nothing of this kind at my own house, however I bear with it in others." The Pantagruelian feast which such interruptions helped the diners to digest often ended in an orgy whose indecency was aggravated by the incredible lack of embarrassment displayed. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Banquet of Trimalchio from the Satyricon

The following is a excerpt from the comic romance “Satyricon” probably composed during the reign of Nero (A.D. 37-68). The depiction of Trimalchio, the fictitious, uncouth former slave, who has nothing good about him except his money, and who is surrounded by sycophants, flatterers and people expected to serve or amuse him, is regarded as “one of the most clever and unsparing delineations in ancient literature.”

Petronius Arbiter (A.D. c.27-66) wrote in “Satyricon“:“At last we went to recline at table where boys from Alexandria poured snow water on our hands, while others, turning their attention to our feet, picked our nails, and not in silence did they perform their task, but singing all the time. I wished to try if the whole retinue could sing, and so I called for a drink, and a boy, not less ready with his tune, brought it accompanying his action with a sharp-toned ditty; and no matter what you asked for it was all the same song. [Source: Petronius Arbiter (A.D. c.27-66), “The Banquet of Trimalchio” from the “Satyricon,” William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

“The first course was served and it was good, for all were close up at the table, save Trimalchio, for whom, after a new fashion, the place of honor was reserved. Among the first viands there was a little ass of Corinthian bronze with saddle bags on his back, in one of which were white olives and in the other black. Over the ass were two silver platters, engraved on the edges with Trimalchio's name, and the weight of silver. Dormice seasoned with honey and poppies lay on little bridge-like structures of iron; there were also sausages brought in piping hot on a silver gridiron, and under that Syrian plums and pomegranate grains.

“We were in the midst of these delights when Trimalchio was brought in with a burst of music. They laid him down on some little cushions, very carefully; whereat some giddy ones broke into a laugh, though it was not much to be wondered at, to see his bald pate peeping out from a scarlet cloak, and his neck all wrapped up and a robe with a broad purple stripe hanging down before him, with tassels and fringes dingle-dangle about him.”

See Separate Article: SATYRICON europe.factsanddetails.com

Drinking at a Roman Banquet

A first libation inaugurated the meal. After the hors d'oeuvre a honey wine (mulsum) was served. Between the other courses the ministratores, while replenishing the guests' supply of little hot rolls, solicitously filled their drinking cups with every sort of wine, from those of Marseilles and the Vatican not highly esteemed up to the "immortal Falernian." Wine blent with resin and pine pitch was preserved in amphorae whose necks were sealed with stoppers of cork or clay and provided with a label (pittacium) stating the vintage. The amphorae were uncorked at the feast, and the contents poured through a funnel strainer into the mixing-bowl (crater a) from which the drinking-bowls were filled.[Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Anyone who drank these heavy wines neat was considered abnormal and vicious, a mark for contumely. It was in the cratera that the wine was mixed with water and either cooled with snow or in certain circumstances warmed. The proportion of water was rarely less than a third and might be as high as four-fifths. The commissatio that followed dinner was a sort of ceremonial drinking match in which the cups were emptied at one draught. It was the exclusive right of the master of ceremonies to prescribe the number of cups, imposed equally on all, and the number of cyathi that should be poured into each, which might vary from one to eleven. He also determined the style in which the ceremony should be performed: whether a round should be drunk beginning with the most distinguished person present (a summo), whether each in turn should empty his cup and pass it to his neighbour with wishes for good luck, or whether each should drink the health of a selected guest in a number of cups corresponding to the number of letters in his tria nomina of Roman citizen.

We may well wonder how the sturdiest stomachs could stand such orgies of eating, how the steadiest heads could weather the abuses of the commissationes !Perhaps the number of victims was sometimes smaller than the number of invited guests. There were often, in fact, many called but few chosen at these ostentatious and riotous feasts. Out of vanity, the master of the house would invite as many as possible to dine; then from selfishness or miserliness he would treat his guests inhospitably. Pliny the Elder criticises some of his contemporaries who "serve their guests with other wines than those they drink themselves, or substitute inferior wine for better in the course of the repast." Pliny the Younger condemns severely a host at whose table "very elegant dishes were served up to himself and a few more of the company; while those placed before the rest were cheap and paltry. He had apportioned in small flagons three different sorts of wine," graduated according to the social status of his friends. Martial reproaches Lupus because his mistress "fattens, the adultress, on lewdly shaped loaves, while black meal feeds your guest. Wines of Setia are strained to inflame your lady's snow; we drink the black poison of Corsicanjar."

Finally Juvenal devotes more than a hundred lines to the kind of dinner Virro would offer a poor client. This low-born upstart "himself drinks wine bottled from the hills of Alba or Setia whose date and name have been effaced by the soot which time has gathered on the aged jar"; for him "a delicate loaf is reserved, white as snow and kneaded of the finest flour," for him the huge lobster, garnished with asparagus... a mullet from Corsica... the finest lamprey the Straits of Sicily can purvey... a goose's liver, a capon as big as a house, a boar piping hot, worthy of Meleager's steel... truffles and delicious mushrooms... apples whose scent would be a feast, which might have been filched from the African Hesperides.

Round him the while his humble guests must be content with the coarse wine of this year's vintage, "bits of hard bread that have turned mouldy," some "sickly greens cooked in oil that smells of the lamp," "an eel, first cousin to a water-snake... a crab hemmed in by half an egg... toadstools of doubtful quality... and a rotten apple like those munched on the ramparts by a monkey trained by terror of the whip." In vain Pliny the Younger protested against "this modern conjunction of self-indulgence and meanness... qualities each alone superlatively odious, but still more odious when they meet in the same person." Evidence from many sources places it beyond doubt that these practices were widespread. They had at least the advantage of limiting the damage wrought by gluttony at dinner parties.

Vomiting, Pissing and Farting at a Roman Banquet

Silvia Marchetti of CNN wrote: Gorging for hours on end also called for what we would consider untoward social behavior in order to accommodate such gluttonous indulgences. “They had bizarre culinary habits that don’t sit well with modern etiquette, such as eating while lying down and vomiting between courses,” Franchetti said. These practices helped keep the good times rolling. “Given banquets were a status symbol and lasted for hours deep into the night, vomiting was a common practice needed to make room in the stomach for more food. The ancient Romans were hedonists, pursuing life’s pleasures,” said Jori, who is also an author of several books on Rome’s culinary culture. [Source: Silvia Marchetti, CNN, December 25, 2023]

It was, in fact, customary to leave the table to vomit in a room close to the dining hall. By using a feather, revelers would tickle the back of their throats to stimulate the urge to regurgitate, Jori said. In keeping with their high social status, defined by not having to engage in manual labor, guests would simply return to the banquet hall while slaves cleaned up their mess. Gaius Petronius Arbiter’s literary masterpiece “The Satyricon” captures this typical social dynamic of Roman society in mid first century AD with the character of wealthy Trimalchio, who tells a slave to bring him a “piss pot” so he can urinate. In other words, when nature called, revelers didn’t necessarily go to the bathroom; often the WC came to them, powered again by slave labor.

Martial tells of more than one who simply clicked his fingers for a slave to bring him "a necessary vase" into which he "remeasured with accuracy the wine he had drunk from it," while the slave "guides his boozy master's drunken person." Finally it was not infrequent during the cena to see priceless marble mosaics of the floor defiled with spitting. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

It was also considered normal to break wind while eating, because it was believed that trapping gas inside the bowels could cause death, Jori said. Emperor Claudius, who reigned from 41 AD to 54 AD, is said to have even issued an edict to encourage flatulence at the table, based on writings in the “Life of Claudius” by Roman historian Suetonius.Food leftovers and meat and fish bones were thrown on the floor by guests. To get a sense of the scene, consider one mosaic found in a Roman villa in Aquileia, which depicts fish and food leftovers scattered on the floor. The Romans liked to decorate banquet hall floors with such images in order to camouflage real food strewn on the floor. This trompe-l’oeil tactic, or the “unswept floor” effect, was a clever mosaic technique.

mosaic with items thrown on the floor during a banquet

Vomitorium

A vomitorium is not a room where ancient Romans went to throw up lavish meals so they could return to the table and stuff themselves some more. They were actually part of theaters, so named because it discouraged the audience after a performance. At the 8000-seat marble amphitheater in Aphrodisias in Asia Minor, audiences watched masked and robed actors perform dramas about conspiring slaves and two-timing wives. When the show was over the audience was discouraged out of a gate called the vomitorium .

At the first theaters wooden benches were set up, but later they were replaced by stone or marble seats. The first theaters had a circular orchestra for singers and dancers. This followed the tradition of the early Dionysus festivals when the merrymakers danced around a maypole, altar or image of a god. Theaters built later on had a “ vomitorium”. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Stephanie Pappas wrote in Live Science: As far as pop culture is concerned, a vomitorium is a room where ancient Romans went to throw up lavish meals so they could return to the table and feast some more. It's a striking illustration of gluttony and waste, and one that makes its way into modern texts. Suzanne Collins' "The Hunger Games" series, for example, alludes to vomitoriums when the lavish inhabitants of the Capitol—all with Latin names like Flavia and Octavia—imbibe a drink to make them vomit at parties so they can gorge themselves on more calories than citizens in the surrounding districts would see in months. [Source Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, August 28, 2016]

But the real story behind vomitoriums is much less disgusting. Actual ancient Romans did love food and drink. But even the wealthiest did not have special rooms for purging. To Romans, vomitoriums were the entrances/exits in stadiums or theaters, so dubbed by a fifth-century writer because of the way they'd spew crowds out into the streets. "It's just kind of a trope," that ancient Romans were luxurious and vapid enough to engage in rituals of binging and purging, said Sarah Bond, an assistant professor of classics at the University of Iowa.

The Roman writer Macrobius first referred to vomitoriums in his "Saturnalia." The adjective vomitus already existed in Latin, Bond told Live Science. Macrobius added the "orium" ending to turn it into a place, a common type of wordplay in ancient Latin. He was referring to the alcoves in amphitheaters and the way people seemed to erupt out of them to fill empty seats.

At some point in the late 19th or early 20th century, people got the wrong idea about vomitoriums. It seems likely that it was a single linguistic error: "Vomitorium" sounds like a place where people would vomit, and there was that pre-existing trope about gluttonous Romans.

Classically trained poets and writers at the time would have been exposed to a few sources that painted ancient Romans as just the sort of people who would vomit just to eat more. One source was Seneca, the Stoic who lived from 4 B.C. to A.D. 65 and who gave the impression that Romans were an emetic bunch. In one passage, he wrote of slaves cleaning up the vomit of drunks at banquets, and in his Letter to Helvia, he summarized the vomitorium idea succinctly but metaphorically, referring to what he saw as the excesses of Rome: "They vomit so they may eat, and eat so that they may vomit."

Why Roman Men Reclined at a Banquet and Didn't Pick Up Dropped Food

Silvia Marchetti of CNN wrote: Bloating was reduced by eating lying down on a comfortable, cushioned chaise longue. The horizontal position was believed to aid digestion — and it was the utmost expression of an elite standing. “The Romans actually ate lying on their bellies so the body weight was evenly spread out and helped them relax. The left hand held up their head while the right one picked up the morsels placed on the table, bringing them to the mouth. So they ate with their hands and the food had to be already cut by slaves,” Jori said. Lying down also allowed feast goers to occasionally doze off and enjoy a quick nap between courses, giving their stomach a break.[Source: Silvia Marchetti, CNN, December 25, 2023]

The act of reclining while dining, however, was a privilege reserved for men only. A woman either ate at another table or knelt or sat down beside her husband while he enjoyed his meal. An ancient Roman fresco of a banquet scene at Casa dei Casti Amanti in Pompeii, for example, depicts a man reclining while two women kneel on either side of him. One of the women tends to the man by helping him hold a horn-shaped drinking vessel called a rhyton. Another fresco from Herculaneum, displayed at Naples’ National Archaeological Museum, depicts a woman seated close to a man who is lying down while also raising a rhyton. Men’s horizontal eating position was a symbol of dominance over women. Roman women established the right to eat with their husbands at a much later stage in the history of ancient Rome; it was their first social conquest and victory against sexual discrimination,” Jori explained.

The Romans were also very superstitious. Anything that fell from the table belonged to the afterworld and was not to be retrieved for fear that the dead would come seek vengeance, while spilling salt was a bad omen, Franchetti said. Bread had to be solely touched with the hands and eggshells and mollusks had to be cracked. Were a rooster to sing at an unusual hour, servants were sent to fetch one, kill it and serve it pronto. Feasting was a way to keep death at bay, according to Franchetti. Banquets ended with a binge-drinking ritual during which diners discussed death to remind themselves to fully live and enjoy life — in short, carpe diem. In keeping with this world view, table objects, such as salt and pepper holders, were shaped as skulls. According to Jori, it was customary to invite beloved dead ones to the meal and serve them platefuls of food. Sculptures representing the dead sat at the table with the living.

Perhaps in the ultimate symbol of excess, the epicure Apicius allegedly committed suicide because he had gone broke after throwing too many lavish banquets. He left behind, however, a gastronomic legacy, including his famous Apicius pie made with a mix of fish and meat such as bird interiors and pig’s breasts. A dish that might struggle to entice at modern feasting tables today.

Ton of Cattle Bones Found in Cornith: Sign of Annual Feasts?

In 2013, archaeologist said that a metric ton of cattle bones found in an abandoned theater in Corinth may have been the remnants of large annual feasts. Stephanie Pappas wrote in LiveScience: “The huge amount of bones — more than 1,000 kilograms (2,205 pounds) — likely represent only a tenth of those tossed out at the site in Peloponnese, Greece, said study researcher Michael MacKinnon, an archaeologist at the University of Winnipeg. “What I think that they’re related to are episodes of big feasting in which the theater was reused to process carcasses of hundreds of cattle,” MacKinnon told LiveScience. He presented his research Friday (Jan. 4) at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America in Seattle. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, LiveScience Senior Writer, January 9, 2013 ||*||]

“A theater may seem an odd place for a butchery operation, MacKinnon said, but this particular structure fell into disuse between A.D. 300 A.D. and A.D. 400. Once the theater was no longer being used for shows, it was a large empty space that could have been easily repurposed, he said. The cattle bones were unearthed in an excavation directed by Charles Williams of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. They’d been discarded in that spot and rested there until they were found, rather than being dragged to the theater later with other trash, MacKinnon said. “Some of the skeletal materials were even partially articulated [connected], suggesting bulk processing and discard,” MacKinnon said. ||*||

“MacKinnon and his colleagues analyzed and catalogued more than 100,000 individual bones, most cattle with some goat and sheep. The bones of at least 516 individual cows were pulled from the theater. Most were adults, and maturity patterns in the bones and wear patterns on the teeth showed them all to have been culled in the fall or early winter. “These do not appear to be tired old work cattle, but quality prime stock,” MacKinnon said. It’s impossible to say how quickly the butchering episodes took place, MacKinnon said, though it could be on the order of days or months. The bones were discarded in layers, likely over a period of 50 to 100 years, he said. ||*||

“The periodic way the bones were discarded plus the hurried cut marks on some of the bones suggest a large-scale, recurring event, MacKinnon said. He suspects the cattle were slaughtered for annual large-scale feasts. Without refrigeration, it would have been difficult to keep meat fresh for long, so may have been more efficient for cities to take a communal approach. “What goes around comes around, so maybe we’ll do it this year and next year, it’s the neighbor’s turn to do it,” MacKinnon speculated. “Neighborhoods might sponsor these kinds of things, so people do it to curry favor.” The next step, MacKinnon said, is to look for other possible signs of ancient feasting at different sites. “Maybe there are some special pots, or maybe we’ll find big communal cauldrons or something,” he said. “Something that gives a material record of a celebration.”“ ||*||

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024