UPPER CLASSES AND RICH IN ANCIENT ROME

aristocratic boy

The upper classes and elite consisted of landowners, military officers, government officials and administrators and wealthy soldier-landowners who were similar to medieval knights. Together they made up less than 1 percent of the population. Rich Romans had land, slaves, livestock and wealth. They could easily be identified by their clothes. The historian Michael Grant said the standard of grand villas built in Pompeii "was never achieved again until the 19th century, To pay for their indulgences, many rich Romans, particularly in Italy, exploited the slaves, farmers and peasants under their control. One scholar wrote: "They were permitted to do a great deal — as long as they did nothing constructive.”

The historian William Stearns Davis wrote: “Great fortunes under the Empire fell into two general classes — those founded on commerce, and those founded on land. A good instance of the latter is here cited from Pliny the Elder. Isidorus must have been a great territorial lord — almost a petty prince upon his vast domains. It was estates like his — worked by cheap slave labor — which ruined the honest peasant farmers of Italy.”

On “A Wealthy Roman's Fortune,” Pliny the Elder (23/4-79 A.D.) wrote in “Natural History”, XXXIII.47: “Gaius Caecilius Claudius Isidorus in the consulship of Gaius Asinius Gallus and Gaius Marcius Censorinus [8 B.C.] upon the sixth day before the kalends of February declared by his will, that though he had suffered great losses by the civil wars, he was still able to leave behind him 4,116 slaves, 3,600 yoke of oxen, and 257,000 head of other kinds of cattle, besides in ready money 60,000,000 sesterces. Upon his funeral he ordered 1,100,000 sesterces to be expended. [Source: Pliny the Elder (23/4-79 A.D.), “Natural History,” XXXIII.47: “A Wealthy Roman's Fortune,” William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Patricians and Plebeians: The Origin of the Roman State” by Richard E. Mitchell (1990) Amazon.com;

“Money and Power in the Roman Republic” by H Beck, M Jehne, et al. (2016) Amazon.com;

“Leisure and Luxury in the Age of Nero: The Villas of Oplontis Near Pompeii” by Elaine K. Gazda, John R. Clarke , et al. (2016) Amazon.com;

“Constructing Autocracy: Aristocrats and Emperors in Julio-Claudian Rome”

by Matthew B. Roller (2016) Amazon.com;

“Patricians and Emperors: The Last Rulers of the Western Roman Empire”

by Ian Hughes MA (2020) Amazon.com;

"Roman Society: A Social, Economic, and Cultural History”

by Henry Boren (1991) Amazon.com;

“Roman Social Relations, 50 B.C. to A.D. 284" by Samsay MacMullen (1974) Amazon.com;

“The Satyricon” (Penguin Classics) by Petronius (Gaius Petronius Arbiter Amazon.com

“Luxus: The Sumptuous Arts of Greece and Rome” by Kenneth Lapatin (2015) Amazon.com;

“Living Theatre in the Ancient Roman House: Theatricalism in the Domestic Sphere”

by Richard C. Beacham, Hugh Denard Amazon.com;

“Roman Aristocrats in Barbarian Gaul: Strategies for Survival in an Age of Transition”

by Ralph Whitney Mathisen (2023) Amazon.com;

“Aristocrats and Statehood in Western Iberia, 300-600 C.E.” by Damián Fernández (2017) Amazon.com;

“Crassus: The First Tycoon” by Peter Stothard (2023) Amazon.com;

“Marcus Crassus and the late Roman Republic” by Allen Mason Ward (1977) Amazon.com;

“Roman Lives: A Selection of Eight Roman Lives” (Oxford World's Classics) by Plutarch (2009) Amazon.com;

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City” by Marisa Ranieri Panetta (2023) Amazon.com;

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Lifestyle of Rome's Upper Classes

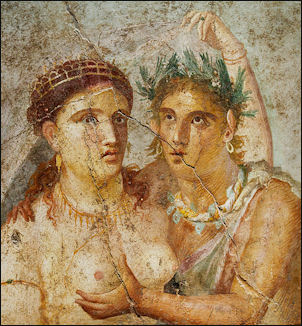

Aristocratic women lived a pampered lifestyle. They wore expensive clothes and sported elaborate hairdos that resembled beehives of curls. These women most likely spent their days gambling, gossiping, attending the theater and shopping. Cleopatra and Antony ate pearls. One patrician gave a jeweled bracelet to his pet eel. A fresco uncovered in a banquet room in Pompeii shows a upper class man have his hair teased and wine feed to him by three lovely bare-breasted women. The scenes look just like something taken out of films on Roman decadence such as Fellini's Roma and Penthouse's Caligula.

The upper class of Rome have been called "rentiers'', or people of means. They were the large landlords whose land wealth in the provinces had gained them admission to the 'Curia and entailed their residence in Rome; men of means, the scribes attached to the offices of the various magistrates, whose posts were bought and sold like those of the French monarchy under the ancien regime; men of means, no less, the administrators and shareholders of the tax-gathering societies whose tenders were guaranteed by capital funds and whose profits swelled their revenues; men of means, again, the innumerable functionaries punctually paid by the Exchequer, who impressed on every part of the imperial government the master's seal; men of means, the 150,000 paupers whom Annona fed at State expense, idlers chronically out of work and well satisfied to be so, who limited their toil to claiming once a month the provisions to which they had once for all established a right until their death. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Petronius wrote: The world entire was in the hands of the victorious Romans. They possessed the earth and the seas and the double field of stars, and were not satisfied. Their keels, weighed down with heavy cargoes, ploughed furrows in the waves. If there was afar some hidden gulf, some unknown continent, which dared to export gold, it was an enemy and the Fates prepared murderous wars for the conquest of new treasures. Vulgarised joys had no more charm, nor the pleasures worn threadbare in the rejoicings of the plebs. The simple soldier caressed the bronzes of Corinth.... Here the Numidians, there the Seres, wove for the Roman new fleeces, and for him the Arab tribes plundered their steppes.

One of Rome's most famous actors, a man named Aesop (not to be confused with the fable writer) once ate a pie, costing the equivalent of thousands of dollars, made of birds that "could imitate the human voice." His son Clodius, with equally expensive tastes, demanded that every meal he ate be season with a "powered gemstone." [People's Almanac]

Crassus, Rome's Richest Man

Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53 B.C.) has of been described at Rome’s richest man. Born into a wealthy family, he acquired his riches, according to Plutarch, through "fire and rapine." Crassus became so powerful that he financed the army that put down the slave revolt led by Spartacus. To celebrate Spartacus's crucifixion, Crassus hosted a banquet for the entire voting public of Rome (10,000 people) that lasted for several days. Each participant was also given an allowance of three months of grain. His ostentatious displays gave us the word crass.

Crassus made a fortune in real estate by controlled Rome's only fire department acquiring the land from property owners victimized by fire.. When a fire broke out, a horse drawn water tank was dispatched to the site, but before fire was put out, Crassus or one of his representatives haggled over the price of his services, often while the house was burning down before their eyes. To save the building Crassus often required the owner to fork over title to the property and then pay rent.

Crassus was most likely the largest property owner in Rome. He also purchased property with money obtained through underhanded methods. While serving as a lieutenant in the civil war of 88-82 he able to buy land formally held by the enemy at bargain prices, sometimes by murdering its owners. Crassius also opened a profitable training center for slaves. He purchased unskilled bondsmen, trained them and then sold them as slaves for a handsome profit.

Crassus was not unlike successful modern businessmen who contribute large sums of money to a political parties in return for favors or high level government positions. He gave loans to nearly every Senator and hosted lavish parties for the influential and powerful. Through shrewd use of his money to gain political influence he reached the position of triumvir, one of the three people responsible for controlling the apparatus of state.

After attaining riches and political power the only left for Crassus to do was lead a Roman army in a great military victory. He purchased an army and sent to Syria by Caesar to battle the Parthians. In 53 B.C. Crassus lost the Battle of Carrhae, one of the Roman Empire's worst defeats. He was captured by the Parthians, who according to legend, poured molten gold down his throat when they realized he was the richest man in Rome. The reasoning of the act was that his lifelong thirst for gold should quenched in death.

See Separate Article: CRASSUS — ANCIENT ROME'S RICHEST MAN europe.factsanddetails.com

Defining Who Is Rich in Ancient Rome

What weight could their modest little fortune of 400,000 sesterces carry, compared with the millions and tens of millions that were at the disposal of the real magnates of the city? Senators from the provinces, whose estates and enterprises were so extensive as to procure them a place among the "most illustrious" (clarissimi) and a seat in the Senate House, came to Rome not only to fulfil their civic functions or supervise the properties which they had been obliged to acquire in Italy, but first and foremost to render their name and the country of their origin illustrious by the magnificence of their Roman mansion and the distinction of the rank they had attained in the Urbs. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Now how could the capitalist with 400,000 compete with them?' or with the equites who had reached the highest posts open to them and grown fat as they mounted the successive rungs of the administrative ladder, handling matters of finance and of supply? Or how even compete with these liberti who, in nursing the wealth of the emperor and his nobles, had amassed great fortunes for themselves? Rome, mistress of the world, drained all its riches. Making due allowance for the difference of time and manners, I cannot believe that the concentrations of capital in Rome from the principate of Trajan onwards can have been much less than they are in our twentieth century among the financiers of "The City" or the bankers of Wall Street.

Some Roman capitalists owned many houses in different quarters of the metropolis. Martial directed this epigram against a certain Maximus: You have a house on the Esquiline and another on the Hill of Diana; the Vicus Patricius boasts a roof of yours. From one you survey the shrine of widowed Cybele; from another the Temple of Vesta; from here the new, from there the ancient Temple of Jove. Tell me where I can call upon you or in what quarter I may look for you. The man, O Maximus, who is.everywhere at home is a man without a home at all.

No one could reckon himself rich under 20,000,000. Pliny the Younger, the ex-consul and perhaps the greatest advocate of his day, whose will disclosed a sum closely approaching this, contended nevertheless that he was not rich, and makes the statement with evident sincerity. He writes in perfect good faith to Calvina, whose father owed him 100,000 sesterces, a debt which Pliny generously cancelled, that his means were very limited (modicae facilitates) and that, owing to the way his minor estates were being worked, his income was both small and fluctuating, so that he had to lead a frugal existence. It is true that a freedman like Trimalchio, whose estate Petronius estimated at 30,000,000, was better off than Pliny; and the unknown Afer whom Martial caricatures, whose income from real estate alone amounted to 3,000,000, was three times as wealthy. Nevertheless Pliny's fortune fifty times that of an eques was in the same bracket as theirs, and there was really no common measure between it and the incomes of the "middle classes." The petit bourgeois was literally crushed by the great, and his sole consolation was to see even these enormous fortunes of the wealthy overborne in their turn by the incalculable riches of the emperor.

Careers of the Nobles

The nobles inherited certain of the aristocratic notions of the old patriciate. These limited their business activities and had much to do with the corruption of public life in the last century of the Republic. Men in their position were held to be above all manner of work, with the hands or with the head, for the sake of gain. Agriculture alone was free from debasing associations, as it has been in England until recent times, and statecraft and war were the only careers fit to engage the energies of these men. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Even as statesmen and generals, too, they served their fellow citizens without material reward, for no salaries were drawn by the senators, no salaries attached to the magistracies or to positions of military command. This theory had worked well enough in the time before the Punic Wars, when every Roman was a farmer, when the farmer produced all that he needed for his simple wants, when he left his farm only to serve as a soldier in his young manhood or as a senator in his old age, and returned to his fields, like Cincinnatus, when his services were no longer required by his country. Under the aristocracy of later times, however, the theory subverted every aim that it was intended to secure. |+|

“Agriculture. The farm life that Cicero has described so eloquently and praised so enthusiastically in his Cato Maior would have scarcely been recognized by Cato himself and, long before Cicero wrote, had become a memory or a dream. The farmer no longer tilled his fields, even with the help of his slaves. The yeoman class had largely disappeared from Italy. Many small holdings had been absorbed in the vast estates of the wealthy landowners, and the aims and methods of farming had wholly changed. This is discussed elsewhere, and it will be sufficient here to recall the fact that in Italy grain was no longer raised for the market, simply because the market could be supplied more cheaply from overseas. The grape and the olive had become the chief sources of wealth, and Sallust and Horace complained that for them less and less space was being left by the parks and pleasure grounds. Still, the making of wine and oil under the direction of a careful steward must have been very profitable in Italy, and many of the nobles had plantations in the provinces as well, the revenues of which helped to maintain their state at Rome. Further, certain industries that naturally arose from the soil were considered proper enough for a senator, such as the development and management of stone quarries, brickyards, tile works, and potteries.” |+|

Equites: Roman Knights and Capitalists

Equites at a cavalry re-enactment

The name of knight (eques) had lost its original significance long before the time of Cicero. The equites had become the class of capitalists who found in financial transactions the excitement and the profit that the nobles found in politics and war. Under the Empire certain important administrative posts were turned over to the equites, and there came to be a regular equestrian cursus honorum, but the equites continued to be on the whole the business class. It was the immense scale of their operations that relieved them from the stigma that attached to working for gain just as in modern times the wholesale dealer may have a social position entirely beyond the hopes of the small retailer. From early times their syndicates had financed and carried on great public works of all sorts, bidding for the contracts let by the magistrates. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Though “big business” never exerted the power at Rome attributed to it in modern times, in the later years of the Republic the equites as a body exerted considerable political influence, holding in fact the balance of power between the senatorial and the democratic parties. As a rule they exerted this influence only so far as was necessary to secure legislation favorable to them as a class, and to insure as governors for the provinces men that would not look too closely into their transactions there. For in the provinces the knights as well as the nobles found their best opportunities. Their chief business in the provinces was collecting the revenues on a contract basis. For this purpose syndicates were formed, which paid into the public treasury a lump sum fixed by the senate, and reimbursed themselves by collecting what they could from the province. While the system lasted, the profits were far beyond all reason, and the word “publican” became a synonym for “sinner.” Besides farming the revenues, the equites “financed” provinces and allied states, advancing money to meet the ordinary or extraordinary expenses. Sulla levied a contribution of 20,000 talents (about $20,000,000) in Asia. |+|

“The money was advanced by a syndicate of Roman capitalists, and they had collected the amount six times over, when Sulla interfered, for fear that there would be nothing left for him in case of future needs. More than one pretender was set upon a puppet throne in the East in order to secure the payment of sums previously lent to him by the capitalists. The operations of the equites as individuals were only less extensive and less profitable. The grain in the provinces, the wool, and the products of mines and factories could be moved only with the money advanced by them. They ventured also to engage in commercial enterprises abroad that were barred against them at home, doing the buying and selling themselves, not merely supplying the money to others. They lent money to individuals, too, though at Rome money-lending was discreditable. The usual rate of interest was twelve per cent, but Marcus Brutus was lending money at forty-eight per cent in Cilicia, and trying to collect compound interest, too, when Cicero went there as governor in 51 B.C., and he expected Cicero to enforce his demands for him.” |+|

Honestiores

In the Roman empire of the A.D. second and third centuries a legal distinction arose which divided the citizen body into two classes: the honestiores and the humiliores, also called plebeii or tenuiores. To the first class belonged Roman senators and knights with their families, soldiers and veterans with their children, and men who held or had held municipal offices in towns and cities outside of Rome, with their descendants. All other citizens belonged to the second, and unless wealth or ability brought them into public office, they remained there. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The two highest groups among the honestiores were known as "orders" (ordines) and were composed respectively of senators and knights. The members of the lower or Equestrian Order had to possess a minimum of 400,000 sesterces. If they were honored by the confidence of the emperor they were then qualified to be given command of his auxiliary troops or to fulfill a certain number of civil functions reserved for them; they could become domanial or fiscal procurators, or governors of secondary provinces like those of the Alps or Mauretania. After Hadrian's time they could hold various posts in the imperial cabinet, and after Augustus they were eligible for any of the prefectures except that of praejectus urbi.

At the summit of the social scale was the Senatorial Order. A member of this order had to own at least 1,000,000 sesterces ($40,000). The emperor could at will appoint him to command his legions, to act as legate or proconsul in the most important provinces, to administer the chief services of the city, or to hold the highest posts in the priesthood. An ingenious hierarchy gradually established barriers between the different ranks of the privileged, and to make these demarcations more evident Hadrian bestowed on each variety its own exclusive title of nobility. Among the knights, "distinguished man" (vir egregius) served for a mere procurator; "very perfect man" (vir perfectissimus) for a prefect unless he were a praetor, who was. "most eminent" (vir eminentissimus), a title later restored by the Roman Church for the benefit of her cardinals; while the epithet "most famous" (vir clarissimus) was reserved for the senator and his immediate relatives.

Decadence of the Rich in A.D. 4th Century Rome

William Stearns Davis wrote: “The following was written only about a generation before Alaric plundered Rome in 410 CE. Ammianus Marcellinus, who observed Rome on a visit, saw the city as full of emptiness, shallowness, and as lacking of all real culture.”

On the Luxury of the Rich in Rome in A.D. 400, Ammianus Marcellinus (c.330-395 A.D.) wrote in “History”: “Rome is still looked upon as the queen of the earth, and the name of the Roman people is respected and venerated. But the magnificence of Rome is defaced by the inconsiderate levity of a few, who never recollect where they are born, but fall away into error and licentiousness as if a perfect immunity were granted to vice. Of these men, some, thinking that they can be handed down to immortality by means of statues, are eager after them, as if they would obtain a higher reward from brazen figures unendowed with sense than from a consciousness of upright and honorable actions; and they are even anxious to have them plated over with gold! [Source: Ammianus Marcellinus (c.330-395 A.D.), “History, XIV.16: The Luxury of the Rich in Rome, c. 400 A.D. William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 224-225, 239-244, 247-258, 260-265, 305-309]

“Others place the summit of glory in having a couch higher than usual, or splendid apparel; and so toil and sweat under a vast burden of cloaks which are fastened to their necks by many clasps, and blow about by the excessive fineness of the material, showing a desire by the continual wriggling of their bodies, and especially by the waving of the left hand, to make more conspicuous their long fringes and tunics, which are embroidered in multiform figures of animals with threads of divers colors.

“Others again, put on a feigned severity of countenance, and extol their patrimonial estates in a boundless degree, exaggerating the yearly produce of their fruitful fields, which they boast of possessing in numbers, from east and west, being forsooth ignorant that their ancestors, who won greatness for Rome, were not eminent in riches; but through many a direful war overpowered their foes by valor, though little above the common privates in riches, or luxury, or costliness of garments.

“If now you, as an honorable stranger, should enter the house of any passing rich man, you will be hospitably received, as though you were very welcome; and after having had many questions put to you, and having been forced to tell a number of lies, you will wonder — since the gentleman has never seen you before — that a person of high rank should pay such attention to a humble individual like yourself, so that you become exceeding happy, and begin to repent not having come to Rome ten years before. When, however, relying on this affability you do the same thing the next day, you will stand waiting as one utterly unknown and unexpected, while he who yesterday urged you to "come again," counts upon his fingers who you can be, marveling for a long time whence you came, and what you can want. But when at last you are recognized and admitted to his acquaintance, if you should devote yourself to him for three years running, and after that cease with your visits for the same stretch of time, then at last begin them again, you will never be asked about your absence any more than if you had been dead, and you will waste your whole life trying to court the humors of this blockhead.

“But when those long and unwholesome banquets, which are indulged in at periodic intervals, begin to be prepared, or the distribution of the usual dole baskets takes place, then it is discussed with anxious care, whether, when those to whom a return is due are to be entertained, it is also proper to ask in a stranger; and if after the question has been duly sifted, it is determined that this may be done, the person preferred is one who hangs around all night before the houses of charioteers, or one who claims to be an expert with dice, or affects to possess some peculiar secrets. For hosts of this stamp avoid all learned and sober men as unprofitable and useless — with this addition, that the nomenclators also, who usually make a market of these invitations and such favors, selling them for bribes, often for a fee thrust into these dinners mean and obscure creatures indeed.

Emperor Caracalla

“The whirlpool of banquets, and divers other allurements of luxury I omit, lest I grow too prolix. Many people drive on their horses recklessly, as if they were post horses, with a legal right of way, straight down the boulevards of the city, and over the flint-paved streets, dragging behind them huge bodies of slaves, like bands of robbers. And many matrons, imitating these men, gallop over every quarter of the city, with their heads covered, and in closed carriages. And so the stewards of these city households make careful arrangement of the cortege; the stewards themselves being conspicuous by the wands in their right hands. First of all before the master's carriage march all his slaves concerned with spinning and working; next come the blackened crew employed in the kitchen; then the whole body of slaves promiscuously mixed with a gang of idle plebeians; and last of all, the multitude of eunuchs, beginning with the old men and ending with the boys, pale and unsightly from the deformity of their features.

“Those few mansions which were once celebrated for the serious cultivation of liberal studies, now are filled with ridiculous amusements of torpid indolence, reechoing with the sound of singing, and the tinkle of flutes and lyres. You find a singer instead of a philosopher; a teacher of silly arts is summoned in place of an orator, the libraries are shut up like tombs, organs played by waterpower are built, and lyres so big that they look like wagons! and flutes, and huge machines suitable for the theater. The Romans have even sunk so far, that not long ago, when a dearth was apprehended, and the foreigners were driven from the city, those who practiced liberal accomplishments were expelled instantly, yet the followers of actresses and all their ilk were suffered to stay; and three thousand dancing girls were not even questioned, but remained unmolested along with the members of their choruses, and a corresponding number of dancing masters.

“On account of the frequency of epidemics in Rome, rich men take absurd precautions to avoid contagion, but even when these rules are observed thus stringently, some persons, if they be invited to a wedding, though the vigor of their limbs be vastly diminished, yet when gold is pressed in their palm they will go with all activity as far as Spoletum! So much for the nobles. As for the lower and poorer classes some spend the whole night in the wine shops, some lie concealed in the shady arcades of the theaters. They play at dice so eagerly as to quarrel over them, snuffing up their nostrils, and making unseemly noises by drawing back their breath into their noses: — or (and this is their favorite amusement by far) from sunrise till evening, through sunshine or rain, they stay gaping and examining the charioteers and their horses; and their good and bad qualities. Wonderful indeed it is to see an innumerable multitude of people, with prodigious eagerness, intent upon the events of the chariot race!”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024