FAMILY LIFE IN ANCIENT ROME

The family was regarded by the early Romans as the most important and sacred of all human institutions. At its head was the household father (paterfamilias). He was supreme ruler over all the members of the household; his power extended to life and death. He had charge of the family worship and performed the religious rites about the sacred fire, which was kept burning upon the family altar. Around the family hearth were gathered the sons and daughters, grandsons and granddaughters, and also, the adopted children,—all of whom remained under the power of the father as long as he lived. The family might also have dependent members, called “clients,” who looked up to the father as their “patron”; and also slaves, who served the father as their master. Every Roman looked with pride upon his family and the deeds of his ancestors; and it was regarded as a great calamity for the family worship to become extinct. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Jana Louise Smit wrote for Listverse: “Roman families would be both recognizable and unrecognizable today. Their strict social classes and lawful human rights violations will make any rational person glad to be alive in the 21st century. On the other hand, their homelier moments are eternal. Like today, children played similar games, the whole family coddled pets, and they enjoyed the finer things in life.” [Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, August 5, 2016]

In attempt to boost the declining birth rate Augustus, in the A.D. 1st century, offered tax breaks for large families and cracked down on abortion. He imposed strict marriage laws and changed adultery from an act of indecency to an act of sedition, decreeing that a man who discovered his wife's infidelity must turn her in or face charges himself. Adulterous couples could have their property confiscated, be exiled to different parts of the empire and be prohibited from marrying one another. Augustus passed the reforms because he believed that too many men spent their energy with prostitutes and concubines and had nothing for their wives, causing population declines.

Under Augustus, women had the right to divorce. Husbands could see prostitutes but not keep mistresses, widows were obligated to remarry within two years, divorcees within 18 months. Parents with three or more children were given rewards, property, job promotions, and childless couples and single men were looked down upon and penalized . The end result of the reforms was a skyrocketing divorce rate.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MARRIED LIFE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT ROME: LAWS, TYPES, TRADITION factsanddetails.com ;

WEDDINGS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LOVE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

DIVORCE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME: STATUS, INEQUALITY, LITERACY, RIGHTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROLES AND VIEWS OF WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Roman Household: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Jane F. Gardner and Thomas Wiedemann (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Family in Ancient Rome”, Illustrated, (1987) by Beryl Rawson Amazon.com;

“The Roman Family” by Suzanne Dixon (1992) Amazon.com

“Marriage, Divorce, and Children in Ancient Rome” by Beryl Rawson (1996) Amazon.com;

”Patriarchy, Property and Death in the Roman Family” by Richard P. Saller (1994) Amazon.com

“The Censors as Guardians of Public and Family Life in the Roman Republic” by Anna Tarwacka (2024) Amazon.com;

“Augustus and the Family at the Birth of the Roman Empire” by Beth Severy (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Family” by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges (1830-1889) Amazon.com;

“Family and Familia in Roman Law and Life” by Jane F. Gardner (1998) Amazon.com;

“A Casebook on Roman Family Law” by Bruce W. Frier , Thomas A. J. McGinn, et al. | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Discovering the Roman Family: Studies in Roman Social History”

by Keith R. Bradley (1991) Amazon.com;

“The Imperial Families of Ancient Rome” by Maxwell Craven (2020) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Familias (Households) in Ancient Rome

family with slave making a sacrifice

“If by our word “family” we understand a group consisting of husband, wife, and children, we may acknowledge at once that it does not correspond exactly to any meanings of the Latin familia, varied as the dictionaries show these to be. Husband, wife, and children did not necessarily constitute an independent family among the Romans, and were not necessarily members even of the same family. The Roman familia, in the sense nearest to that of the English word “family,” was made up of those persons who were subject to the authority of the same Head of the House (pater familias). These persons might make a host in themselves: wife, unmarried daughters, sons, adopted sons, married or unmarried, with their wives, sons, unmarried daughters, and even remoter descendants (always through males), yet they made but one familia in the eyes of the Romans. The Head of such a familia—“household” or “house” is the nearest English word—was always sui iuris (“his own master,” “independent”), while the others were alieno iuri subiecti (“subject to another's authority,” “dependent”). [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The word familia was also very commonly used in a slightly wider sense to include, in addition to the persons named above, all the slaves and clients and all the property real and personal belonging to the pater familias, or acquired and used by the persons under his potestas. The word was also used of the slaves alone, and, rarely, of the property alone. In a still wider and more important sense the word was applied to a larger group of related persons, the gens, consisting of all the “households” (familiae) that derived their descent through males from a common ancestor. This remote ancestor, could his life have lasted through all the intervening centuries, would have been the pater familias of all the persons included in the gens, and all would have been subject to his potestas. Membership in the gens was proved by the possession of the nomen, the second of the three names that every citizen of the Republic regularly had. |+|

“Theoretically this gens had been in prehistoric times one of the familiae, “households,” whose union for political purposes had formed the State. Theoretically its pater familias had been one of the Heads of Houses from whom, in the days of the kings, had been chosen the patres, or assembly of old men (senatus). The splitting up of this prehistoric household in the manner, a process repeated generation after generation, was believed to account for the numerous familiae that, in later times, claimed connection with the great gentes. There came to be, of course, gentes of later origin that imitated the organization of the older gentes. The gens had an organization of which little is known. It passed resolutions binding upon its members; it furnished guardians for minor children, and curators for the insane and spendthrifts. When a member died without leaving heirs, the gens succeeded to such property as he did not dispose of by will and administered it for the common good of all its members. These members were called gentiles, were bound to take part in the religious services of the gens (sacra gentilicia), had a claim to the common property, and might, if they chose, be laid to rest in a common burial ground, if the gens maintained one. Finally, the word familia was often applied to certain branches of a gens whose members had the same cognomen. For this sense of familia a more accurate word is stirps. |+|

Men and Family Values in Ancient Rome

family tombstone

Ancient Rome was strongly patriarchal. Men had absolute power over the household and owned whatever property they lived on. At the head of the family the household father (pater familias) was supreme ruler over all the members of the household; his power extended to life and death. He had charge of the family worship and performed the religious rites about the sacred fire, which was kept burning upon the family altar. Sons needed approval from their fathers to marry, launch a business, and start a career. Their income belonged to their fathers. The stress and pressure that resulted from this arrangement no doubt encouraged sons to murder their fathers and fathers to disinherit their sons. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), \~]

Young men were allowed to, even encouraged, to visit prostitutes and have male lovers but once they got married they were expected to be devoted family men. Children often addressed their fathers as "Sir" and irregardless of whether they were male or female they were under the wing of their father as long as they there alive. Children who disappointed their fathers in some way were sometimes condemned to death by their fathers.

Mos maiorum is translated as "ancestral custom" or "way of the ancestors" and is often compared with the English "mores". Applied to private, political, and military life in ancient Rome, it was the core concept of Roman traditionalism and viewed as a dynamic complement to written law. The Roman familia ("household") and Roman society were was hierarchical. These hierarchies were traditional and self-perpetuating and mos maiorum justified them and gave them support. The pater familias, or head of household, held absolute authority over his familia, which was both an autonomous unit within society and a model for the social order, but he was expected to exercise this power with moderation and to act responsibly on behalf of his family. The risk and pressure of social censure if he failed to live up to expectations was also a form of mos. [Source Wikipedia]

Candida Moss wrote in Daily Beast: Roman law focused on the power and privileges invested in the pater familias (the citizen father and head of household), who were seen as the protectors of minors, their wives, and enslaved persons who lived in their home. Discipline began here: Roman law invested the pater familias with the power to administer punishment and justice within his own household. It was, University of Iowa ancient historian Sarah Bond told me, “quite literally the patriarchy” and “both the young and women were seen as vulnerable and often mentally incapable” of making their own financial decisions. If the father died, therefore, then a different male relative (usually an uncle) was appointed as a guardian (a tutor or curator). With a few exceptions, adult women as well as children needed the approval and support of their male tutor to take any kind of legal action of their own. Technically, their assets were the property of the tutor for as long as the tutelage continued. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 25, 2021]

The basis for this whole system, Bond said, was the power of the father as the supreme authority in the lives of women and children. The only way a woman could hope to gain any kind of personal legal status was through childbearing. The ius liberorum introduced by Augustus around the turn of the Era granted women who had had three children the opportunity to escape from the constant oversight of guardianship. For male children tutelage and curatorship ended when they became men in their teens, but could be extended until the age of 25. For female children it could continue in perpetuity.

Daily Life of Men and Women in Ancient Rome

In Trajan's Rome women spent most of their time indoors. If they were poor they attended to the work of the household, until the hour when they could go to the public baths which were reserved for them. If they were rich and had a large household staff to relieve them of domestic cares, they had nothing to do but go out when the fancy took them, pay visits to their women friends, take a walk, attend public spectacles, or later go out to dinner. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The men on the other hand rarely stayed at home.If they had to earn their bread, they hurried off to their business, which in all trade guilds began at dawn. Even if they were unemployed they were no sooner out of bed than they were in the grip of the duties inseparable from being a "client." For it was not only the freedmen who were dependent on the good graces of a patron. From the parasite do-nothing up to the great aristocrat there was no man in Rome who did not feel himself bound to someone more powerful above him by the same obligations of respect, or, to use the technical term, the same obsequium, that bound the ex-slave to the master who had manumitted him.

Patria Potestas: Authority of the Father

Augustus, a short but strong father figure with an out-of-control daughter

“The authority of the pater familias over his descendants was called usually patria potestas, but also patria maiestas, patrium ius, and imperium paternum. It was carried to a greater length by the Romans than by any other people, so that, in its original and unmodified form, the patria potestas seems to us excessive and cruel. As they understood it, the pater familias, in theory, had absolute power over his children and other agnatic descendants. He decided whether or not the new-born child should be reared; he punished what he regarded as misconduct with penalties as severe as banishment, slavery, and death; he alone could own and exchange property—all that those subject to him earned or acquired in any way was his; according to the letter of the law they were little better than his chattels. If his right to one of them was disputed, he vindicated it by the same form of action that he used in order to maintain his right to a house or a horse; if one of them was stolen, he proceeded against the abductor by the ordinary action for theft; if for any reason he wished to transfer one of them to a third person, it was done by the same form of conveyance that he employed to transfer inanimate things. The jurists boasted that these powers were enjoyed by Roman citizens only. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“But however stern this authority was theoretically, it was greatly modified in practice, under the Republic by custom, under the Empire by law. King Romulus was said to have ordained that all sons and all first-born daughters should be reared, and that no child should be put to death until its third year, unless it was grievously deformed. This at least secured life for the child, though the pater familias still decided whether it should be admitted to his household, with the resultant social and religious privileges, or be disowned and become an outcast. King Numa was said to have forbidden the sale into slavery of a son who had married with the consent of his father. But of much greater importance was the check put by custom upon arbitrary and cruel punishments. Custom, not law, obliged the pater familias to call a council of relatives and friends (iudicium domesticum) when he contemplated inflicting severe punishment upon his children, and public opinion obliged him to abide by its verdict. Even in the comparatively few cases when tradition tells us that the death penalty was actually inflicted, we usually find that the father acted in the capacity of a magistrate happening to be in office when the offense was committed, or that the penalties of the ordinary law were merely anticipated, perhaps to avoid the disgrace of a public trial and execution. |+|

“So, too, in regard to the ownership of property the conditions were not really so hard as the strict letter of the law makes them appear to us. It was customary for the Head of the House to assign to his children property, peculium (“cattle of their own”), for them to manage for their own benefit. Furthermore, although the pater familias theoretically held legal title to all their acquisitions, yet practically all property was acquired for and belonged to the household as a whole, and the pater familias was, in effect, little more than a trustee to hold and administer it for the common benefit. This is shown by the fact that there was no graver offense against public morals, no fouler blot on private character, than to prove untrue to this trust (patrimonium profundere). Besides this, the long continuance of the potestas is in itself a proof that its rigor was more apparent than real. |+|

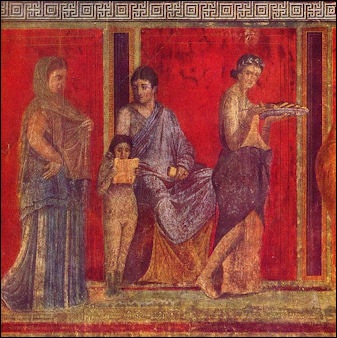

Dominica Potestas: Power of the Father Over His Children and Property

from the Villa de Misteri in Pompeii

Whereas the authority of the pater familias over his descendants was called patria potestas, his authority over his chattels was called dominica potestas. So long as he lived and retained his citizenship, these powers could be terminated only by his own deliberate act. He could dispose of his property by gift or sale as freely as we do now. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“He might “emancipate” his sons, a very formal proceeding (emancipatio) by which they became each the Head of a new House, even if they were childless themselves or unmarried or mere children. He might also emancipate an unmarried daughter, who thus in her own self became an independent familia, or he might give her in marriage to another Roman citizen, an act by which she passed, according to early usage, into the House of which her husband was Head, if he was sui iuris, or into that of which he was a member, if he was still alieno iuri subiectus. It must be noticed, on the other hand, that the marriage of a son did not make him a pater familias or relieve him in any degree from the patria potestas: he and his wife and their children were subject to the Head of his House as he had been before his marriage. On the other hand, the Head of the House could not number in his familia his daughter’s children; legitimate children were under the same patria potestas as their father, while an illegitimate child was from the moment of birth in himself or herself an independent familia. |+|

“The right of a pater familias to ownership in his property (dominica potestas) was complete and absolute. This ownership included slaves as well as inanimate things, for slaves, as well as inanimate things, were mere chattels in the eyes of the law. The influence of custom and public opinion, so far as these tended to mitigate the horrors of their condition, will be discussed later. It will be sufficient to say here that, until imperial times, there was nothing to which the slave could appeal from the judgment of his master. That judgment was final and absolute. |+|

Splitting Up a Household in Ancient Rome

Emancipation was not very common, and it usually happened that the household was dissolved only by the death of its Head. When this occurred, as many new households were formed as there were persons directly subjected to his potestas at the moment of his death: wife, sons, unmarried daughters, widowed daughters-in-law, and children of a deceased son. The children of a surviving son, it must be noticed, merely passed from the potestas of their grandfather to that of their father. A son under age or an unmarried daughter was put under the care of a guardian (tutor), selected from the same gens, very often an older brother, if there was one. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

from the Vasa dei Vettii in Pompeii

“It is assumed that Gaius was a widower who had had five children, three sons and two daughters. Of the sons, Aulus and Appius had married and each had two children; Appius then died. Of the daughters, Terentia Minor had married Marcus and become the mother of two children. When Gaius died, Publius and Terentia were unmarried. Gaius had emancipated none of his children. The following points should be noticed:

“1) The living descendants of Gaius were ten (3, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16); his son Appius was dead. 2) Subject to his potestas were nine (3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14). 3) His daughter Terentia Minor (10) had passed out of his potestas by her marriage with Marcus (9), and her children (15, 16) alone out of all the descendants of Gaius had not been subject to him.

“4) At his death were formed six independent familiae, one consisting of four persons (3, 4, 11, 12), the others of one person each (6, 7, 8, 13, 14). 5) Titus and Tiberius (11, 12) merely passed out of the potestas of their grandfather, Gaius, to come under that of their father, Aulus. 6) If Quintus (13) and Sextus (14) were minors, guardians were appointed for them, as stated above.

The patria potestas was extinguished in various ways: 1) By the death of the pater familias; 2) By the emancipation of a son or a daughter 3) By the loss of citizenship of a son or a daughter 4) If the son became a Flamen Dialis or the daughter a virgo vestalis 5) If either father or child was adopted by a third party 6) If the daughter passed by formal marriage into the power (in manum) of a husband, though this did not essentially change her dependent condition 7) If the son became a public magistrate. In this case the potestas was suspended during the period of office, but, after it expired, the father might hold the son accountable for his acts, public or private, while he held the magistracy.

Agnati

It has been remarked that the children of a daughter could not be included in the familia of her father, and that membership in the larger organization known as the gens was limited to those who could trace their descent through males to a common ancestor, in whose potestas they would be were he alive. All persons related to one another by such descent were called agnati, “agnates.” Agnatio was the closest tie of relationship known to the Romans. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“In the list of agnati were included two classes of persons who would seem by the definition to be excluded. These were 1) the wife, who passed by manus into the family of her husband, becoming by law his agnate and the agnate of all his agnates, and 2) the adopted son. On the other hand a son who had been emancipated was excluded from agnatio with his father and his father’s agnates, and could have no agnates of his own until he married or was adopted into another familia. |+|

“It is supposed that Gaius and Gaia have five children (Aulus, Appius, Publius, Terentia, and Terentia Minor), and six grandsons (Titus and Tiberius, the sons of Aulus, Quintus and Sextus, the sons of Appius, and Servius and Decimus, the sons of Terentia Minor). Gaius has emancipated two of his sons, Appius and Publius, and has adopted his grandson Servius, who had previously been emancipated by his father, Marcus. There are four sets of agnati: 1) Gaius, his wife, and those whose pater familias he is: Aulus, Tullia, the wife of Aulus, Terentia, Titus, Tiberius, and Servius, a son by adoption (1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 11, 12, 15). 2) Appius, his wife, and their two sons (5, 6, 13, 14). 3) Publius, who is himself a pater familias, but has no agnati at all. 4) Marcus, his wife, Terentia Minor, and their child Decimus (9, 10, 16). Notice that the other child, Servius (15), having been emancipated by Marcus, is no longer agnate to his father, mother, or brother, but has become one of the group of agnati mentioned above, under (1).

Cognati and Adfines

Cognati, on the other hand, were what we call blood relations, no matter whether they traced their relationship through males or through females, and regardless of what potestas had been over them. The only barrier in the eyes of the law was loss of citizenship, and even this was not always regarded. Thus, in the table last given, Gaius, Aulus, Appius, Publius, Terentia, Terentia Minor, Titus, Tiberius, Quintus, Sextus, Servius, and Decimus are all cognates with one another. So, too, is Gaia with all her descendants mentioned. So also are Tullia, Titus, and Tiberius; Licinia, Quintus, and Sextus; Marcus, Servius, and Decimus. But husband and wife (Gaius and Gaia, Aulus and Tullia, Appius and Licinia, Marcus and Terentia Minor) are not cognates by virtue of their marriage, though that made them agnates. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“ Public opinion strongly discountenanced the marriage of cognates within the sixth (later the fourth) degree, and persons within this degree were said to have the ius osculi, “the right to kiss.” The degree was calculated by counting from one of the interested parties through the common kinsman to the other. The matter may be understood from this table in Smith’s Dictionary of Antiquities under cognati, or from the one given here Cognates did not form an organic body in the State as the agnates formed the gens, but the twenty-second of February was set aside to commemorate the tie of blood (cara cognatio. On this day presents were exchanged and family reunions were probably held. It must be understood, however, that cognatio gave no legal rights or claims under the Republic.

“Persons connected by marriage only, as a wife with her husband’s cognates and he with hers, were called adfines. There were no formal degrees of adfinitas, as there were of cognatio. Those adfines for whom distinctive names were in common use were gener, son-in-law; nurus, daughter-in-law; socer, father-in-law; socrus, mother-in-law; privignus, privigna, step-son, step-daughter; vitricus, step-father; noverca, step-mother. If we compare these names with the awkward compounds that do duty for them in English, we shall have additional proof of the stress laid by the Romans on family ties; two women who married brothers were called ianitrices, a relationship for which we do not have even a compound. The names of blood relations tell the same story; a glance at the table of cognates will show how strong the Latin is here, how weak the English. We have “uncle,” “aunt,” and “cousin,” but between avunculus and patruus, matertera and amita, patruelis and consobrinus we can distinguish only by descriptive phrases. For atavus and tritavus we have merely the indefinite “forefathers.” In the same way the Latin language testifies to the headship of the father. We speak of the “mother-country” and “mother-tongue,” but to the Roman these were patria and sermo patrius. As the pater stood to the filius, so stood the patronus to the cliens, the patricii to the plebeii, the patres (senators) to the rest of the citizens, and Iuppiter (Jove the Father) to the other gods.

Family Cult

It has been said that agnatio was the closest tie known to the Romans. The importance they attached to the agnatic group is largely explained by their ideas of the future life. They believed that the souls of men had an existence apart from the body, but they did not originally think that the souls were in a separate spiritland. They conceived of the souls as hovering around the place of burial and requiring for its peace and happiness that offerings of food and drink be made to it regularly. Should the offerings be discontinued, the soul, they thought, would cease to be happy, and might even become a spirit of evil to bring harm upon those who had neglected the proper rites. The maintenance of these rites and ceremonies devolved naturally upon the descendants from generation to generation, whom the spirits in turn would guide and guard. Contact with Etruscan and Greek art and myth later brought in such ideas of a place of torment or possible happiness as Vergil gathers up in Book VI of the Aeneid. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The Roman was bound, therefore, to perform these acts of affection and piety so long as he himself lived, and was bound no less to provide for their performance after his death by perpetuating his race and the family cult. A curse was believed to rest upon the childless man. Marriage was, therefore, a solemn religious duty, entered into only with the approval of the gods, ascertained by the auspices. In taking a wife to himself the Roman made her a partaker of his family mysteries, a service that brooked no divided allegiance. He therefore separated her entirely from her father’s family, and was ready in turn to surrender his daughter without reserve to the husband with whom she was to minister at another altar. The pater familias was the priest of the household; those subject to his potestas assisted in the prayers and offerings, the sacra familiaria.

“But it might be that a marriage was fruitless, or that the Head of the House saw his sons die before him. In this case he had to face the prospect of the extinction of his family, and his own descent to the grave with no posterity to make him blessed. One of two alternatives was open to him to avert such a calamity. He might give himself in adoption and pass into another family in which the perpetuation of the family cult seemed certain, or he might adopt a son and thus perpetuate his own family. He usually followed the latter course, because it secured peace for the souls of his ancestors no less than for his own.

Family Recreation in Ancient Rome

Jana Louise Smit wrote for Listverse: “Downtime was a big part of Roman family life. Usually, starting at noon, the upper crust of society dedicated their day to leisure. Most enjoyable activities were public and shared by rich and poor alike, male and female—watching gladiators disembowel each other, cheering chariot races, or attending the theatre. [Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, August 5, 2016]

“Citizens also spent a lot of time at public baths, which wasn’t your average tub and towel affair. A Roman bath typically had a gym, pool, and a health center. Certain locales even offered prostitutes. Children had their own favorite pastimes. Boys preferred to be more active, wrestling, flying kites, or playing war games. Girls occupied themselves with things like dolls and board games. Families also enjoyed just relaxing with each other and their pets.

The Romans loved their bathes and much of Roman social life centered around them. Bathing was both a social duty and a way to relax. During the early days of Roman baths there were no rules about nudity or the mixing of the sexes, or for that matter rules about what people did when they were nude and mixing. For women who had problems with this arrangement there were special baths for women only. But eventually the outcry against promiscuous behavior in the baths forced Emperor Hadrian to separate the sexes. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Most Roman houses, large or small, had a garden. Large homes had one in the courtyard and this was often where the family gathered, socialized and ate their meals. The sunny Mediterranean climate in Italy was usually accommodating to this routine. On the walls of the houses around the garden were paintings of more plants and flowers as well as exotic birds, cows, birdfeeders, and columns, as if the homeowner was trying achieve the same affects as the backdrop on a Hollywood set. Poor families tended small plots in the back of the house, or at least had some potted plants.

Plutarch on Good Parenting

Plutarch wrote in “The Training of Children” (c. A.D. 110): “13. Moreover, I have seen some parents whose too much love to their children has occasioned, in truth, their not loving them at all. I will give light to this assertion by an example, to those who ask what it means. It is this: while they are over-hasty to advance their children in all sorts of learning beyond their equals, they set them too hard and laborious tasks, whereby they fall under discouragement; and this, with other inconveniences accompanying it, cause them in the issue to be ill affected to learning itself. For as plants by moderate watering are nourished, but with over-much moisture are glutted, so is the spirit improved by moderate labors, but overwhelmed by such as are excessive. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

“We ought therefore to give children some time to take breath from their constant labors, considering that all human life is divided betwixt business and relaxation. To which purpose it is that we are inclined by nature not only to wake, but to sleep also; that as we have sometimes wars, so likewise at other times peace; so some foul, so other fair days; and, as we have seasons of important business, so also the vacation times of festivals. And, to contract all in a word, rest is the sauce of labor. Nor is it thus in living creatures only, but in things inanimate too. For even in bows and harps, we loosen their strings, that we may bend and wind them up again. Yes, it is universally seen that, as the body is maintained by repletion and evacuation, so is the mind by employment and relaxation.

“Those parents, moreover, are to be blamed who, when they have committed their sons to the care of pedagogues or schoolmasters, never see or hear them perform their tasks; wherein they fail much of their duty. For they ought, ever and again, after the intermission of some days, to make trial of their children's proficiency; and not intrust their hopes of them to the discretion of a hireling. For even that sort of men will take more care of the children, when they know that they are regularly to be called to account. And here the saying of the king's groom is very applicable, that nothing made the horse so fat as the king's eye.

See Separate Article: CHILD REARING IN ANCIENT GREECE AND ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Augustus' Moral Legislation and Families

Along with attempts to restore the old Roman religion, Roman Emperor Augustus (ruled 27 A.D.–A.D. 14) wished to revive the old morality and simple life of the past. He himself disdained luxurious living and foreign fashions. He tried to improve the lax customs which prevailed in respect to marriage and divorce, and to restrain the vices which he felt were destroying the population of Rome. But it is difficult to say whether these laudable attempts of Augustus produced any real results upon either the religious or the moral life of the Roman people. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

In attempt to boost the declining birth rate Augustus offered tax breaks for large families and cracked down on abortion. He imposed strict marriage laws and changed adultery from an act of indecency to an act of sedition, decreeing that a man who discovered his wife's infidelity must turn her in or face charges himself. Adulterous couples could have their property confiscated, be exiled to different parts of the empire and be prohibited from marrying one another. Augustus passed the reforms because he believed that too many men spent their energy with prostitutes and concubines and had nothing for their wives, causing population declines.

Under Augustus, women had the right to divorce. Husbands could see prostitutes but not keep mistresses, widows were obligated to remarry within two years, divorcees within 18 months. Parents with three or more children were given rewards, property, job promotions, and childless couples and single men were looked down upon and penalized . The end result of the reforms was a skyrocketing divorce rate.

In passing these laws Augustus was prompted by the same impulse that had made him withdraw from the husband's administration any part of the dowry which was invested in land in Italy. In both cases his concern was to safeguard a woman's dowry the unfailing bait for a suitor so as to secure for her the chance of a second marriage. It turned out, however, as he ought to have foreseen, that his measures, comformable though they were to his population policy and socially unexceptionable, hastened the ruin of family feeling among the Romans. The fear of losing a dowry was calculated to make a man cleave to the wife whom he had married in the hope of acquiring it, but nothing very noble was likely to spring from calculations so contemptible. In the long run avarice prolonged the wealthy wife's enslavement of her husband.

While progressively lowering the dignity of marriage, this legislation succeeded in preserving its cohesion only up to the point where a husband, weary of his wife, felt sure of capturing, without undue delay, another more handsomely endowed. In these circumstances, the vaunted laws of Augustus must bear part of the responsibility for the fact, which need surprise no one, that throughout the first two centuries of the empire Latin literature shows us a great many households either temporarily bound together by financial interest or broken up sometimes in spite of, sometimes for the sake of, money.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024