LANGUAGE IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE

Most of the Roman Empire probably spoke Greek or one of its variants rather than Latin, the language traditionally associated with the Romans. When Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, most people in Naples and Pompeii still spoke Greek as their first language. The four Gospels, which were written in the A.D. 1st century, and many famous Roman texts were written in Greek. In A.D. AD when the Roman Empire split into western and eastern (Byzantine) parts, Latin continued to be used as the official language but in time it was replaced by Greek as that language was already widely spoken among the Eastern Mediterranean nations as the main trade language.

Even Latin-speakers didn’t speak the what we regard as Latin today. Jamie Frater wrote for Listverse: “While it is true that the Romans did speak a form of Latin known as vulgar Latin, it was quite different from the Classical Latin that we generally think of them speaking (Classical Latin is what we usually learn at University). Vulgar Latin is the language that the Romance languages (Italian, French, etc.) developed from. Classical Latin was used as an official language only. In addition, members of the Eastern Roman Empire were speaking Greek exclusively by the 4th century, and Greek had replaced Latin as the official language. [Source: Jamie Frater, Listverse, May 5, 2008 ]

There were phrase books and learning materials for those who wished to learn Latin and use some phrases of it in particular situations. Gordon Gora wrote: “If one wished to speak Latin, there were tools to do so: colliquia. These text books not only taught Greek speakers Latin, they taught about a wide variety of situations and how to deal with them in a proper manner.” A few examples of these texts have survived. “There are two portions remaining from the original manuscripts that date from the second and sixth centuries. Some of these situations include one’s first visit to the public baths, what one should do if they arrive at school late, and how to deal with a drunk close relative. The texts were incredibly common and widely available to rich and poor alike. It is believed that the situations described were for role playing, which students would act out to get a feel for the material and speech.” [Source: Gordon Gora September 16, 2016]

On why Latin largely died out along the western Roman Empire, Dr Peter Heather wrote for the BBC: “Roman elites learned to read and write classical Latin to highly-advanced levels through a lengthy and expensive private education, because it qualified them for careers in the extensive Roman bureaucracy. The end of taxation meant that these careers disappeared in the post-Roman west, and elite parents quickly realised that spending so much money on learning Latin was now a waste of time. As a result, advanced literacy was confined to churchmen for the next 500 years.” [Source: Dr Peter Heather, BBC, February 17, 2011]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN LITERATURE: CLASSICS, BOOKS AND THE BOOK MARKET europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Language and Society in the Greek and Roman Worlds” by James Clackson (2015) Amazon.com;

“Law, Language, and Empire in the Roman Tradition” by Clifford Ando (2011) Amazon.com;

“Latin Language and Latin Culture: From Ancient to Modern Times” by Joseph Farrell (2001) Amazon.com;

“Latin: A Course in the Language and Civilization of Ancient Rome, Volume II

by John A Anderson, Frank J Groten, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“Learn Latin from the Romans: A Complete Introductory Course Using Textbooks from the Roman Empire” by Eleanor Dickey (2018) Amazon.com;

“Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction” by Benjamin W. Fortson IV Amazon.com;

“Names of the Ancient Romans: Origin and Development of the Tria Nomina System”

by Aleksandr Koptev (2025) Amazon.com;

“Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet From A to Z” by David Sacks (2004) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Writing in the Græco-Roman East” by Roger S. S Bagnall (2012) Amazon.com;

“Letter Writing in Greco-Roman Antiquity” by Stanley K. Stowers (1986) Amazon.com;

“Graffiti in Antiquity” by Peter Keegan (2014) Amazon.com;

“By Roman Hands: Inscriptions and Graffiti for Students of Latin (English and Latin Edition) by Matthew Hartnett (2012) Amazon.com;

“Graffiti and the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii”

by Kristina Milnor (2014) Amazon.com;

Ancient Peoples in their Own Words: Ancient Writing from Tomb Hieroglyphs to Roman Graffiti” by Michael Kerrigan (2019) Amazon.com;

“Inscriptions in the Private Sphere in the Greco-Roman World” by Rebecca Benefiel and Peter Keegan (2015) Amazon.com;

Latin, the Roman Language

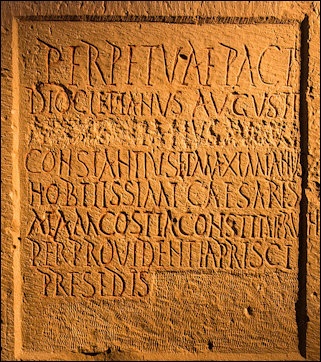

Yotvata inscription from the AD 3rd century

The language of the ancient Romans, Latin is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Classical Latin — originally spoken by the Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area around Rome, Italy — is considered a dead language as it is no longer used to produce major texts, while Vulgar Latin (f Latin spoken from the Late Roman Republic and afterwards) evolved into the Romance Languages. The expansion of the Roman Republic and Imperial Rome brought Latin to all the regions of the Roman Empire. [Source Wikipedia]

A good portion of the words found in English and many other languages are Latin in origin. "The Latin language," wrote T.R. Reid in National Geographic, "was thoroughly rational and pragmatic, a product of careful engineering. For that reason educators throughout the Western world have taught Latin for 2,000 years to help students learn the basic machinery of language." Latin structures such as ablative absolute are even helpful in learning Japanese.

The Roman spoke a language that differs from Latin taught in schools and used during mass in the Catholic church. Like other ancient languages, although we can read it we don’t known exactly what it sounded like. Up until the early 1960s, most American children were taught at least a little Latin in school. Latin words, abbreviations and expression found in English today include: alma mater, alter ego, antebellum, habeas corpus, ignoramuns, in extremis, ipso facto, persona non grata, per capita, prima facie, quid pro quo, sub rosa, vice versa, a.m., p.m., i.e., A.D., R.I.P., e.g., et al, ad infinitum, etc., etc.

Latin was less expressive and more difficult to play with than Greek. With its long monotonous syllables it required a special skill to produce poetry with life. Latin was better for expressing clear, precise thoughts rather than shades of meaning.

Indo-Europeans Languages in Italy

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “All of the languages spoken in prehistoric Italy, with the exception of Etruscan, are members of the Indo-European language family. Working backwards on the basis of similarities among words from different languages and dialects (the comparative method), scholars are able to reconstruct the bare bones of a language they call Proto-Indo-European (PIE). The people who spoke this language were on the move in the latter part of the third and the first half of the second millennia BC. These people, these speakers of PIE, come to us loaded with ideological signification. They are wrapped in the now discredited racist efforts of the Nazis and other groups who sought to make them the archetypal civilizers, the so-called Aryan people from whose bloodline the pure stock of Germany was supposed to descend. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Hence, when we find that leading scholars such as Massimo Pallottino, the dean of Italic prehistory, are more than a little wary about admitting to a massive influx of more advanced PIE-speaking people across the Alps in the Early to Middle Italic Bronze Age, we may suspect that (even if unconsciously) there is more involved in the decision than an impartial assessment of the evidence. Whenever the evidence can bear it, in fact, Pallottino and his school tend to favor a hypothesis of native development to explain and account for major innovations traceable in the archaeological record, as opposed to the influx of new and ethnically different kinds of people. Of course, even Pallottino, with his nativist bent, admits that prior to the Early Bronze Age the people of Italy were in all probability not speaking a dialect of Indo-European, and that the Indo-European language must have come into Italy from outside. ^*^

“The standard line posits a single large ingression of warlike Indo-European speakers, who both tamed and advanced the indigenous population, and whose language and cultural practices spread throughout the peninsula. Pallottino prefers a messier model. He argues that the various Italic dialects, Latin, Osco-Umbrian, and the rest, can not be direct descendants of a single Proto-Italic dialect of PIE. In other words, that Indo-European was introduced into Italy at various times and in various guises, by various different groups of people, who were not conquerors en masse but rather smaller groups who were peacefully absorbed into the existing culture. Burial practice is extremely important for deciding on this question.” ^

The Indo-European group of languages is a language family that originated in western and southern Eurasia. It includes most of the languages of Europe as well as ones from northern Indian subcontinent and Iran. English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Danish, Dutch, Spanish, Hindi, Farsi, Greek, Italian are all Indo-Europe languages. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, of which there are eight groups with languages still alive today: Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, and Italic. An additional six subdivisions are now extinct. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES europe.factsanddetails.com ; INDO-EUROPEANS factsanddetails.com

languages spoken in the Roman Empire

What Happened to Latin

The Latin language used to be spoken all over the Roman Empire. But no country officially speaks it now, at least not in its classic form. But that wasn’t always so. After the Roman Empire fell in the A.D. 5th century, Latin continued to be the lingua franca throughout much of Europe o4 hundreds of years after that. [Source Benjamin Plackett, Live Science, June 1, 2021]

Today, the Vatican and Catholic communities still deliver masses in Latin, but virtually no one in Italy or anywhere else uses Latin on a day-to-day basis. Tim Pulju, a senior lecturer in linguistics and classics at Dartmouth College, told Live Science, "Latin didn't really stop being spoken," Pulju told Live Science. "It continued to be spoken natively by people in Italy, Gaul, Spain and elsewhere, but like all living languages, it changed over time."

Latin changed in the many different regions of the old Roman Empire, and over time these differences grew to create new but closely related languages. "They gradually added up over the centuries, so that eventually Latin developed into a variety of languages distinct from one another, and also distinct from classical Latin," Pulju told Live Science. Those new languages are what we now refer to as the Romance languages, which include French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian and Spanish.

Latin is not a dead language but the Etruscan language, originally spoken in what is modern day Tuscany in Italy and spoken in the Roman ere. "After the Romans conquered Etruria, succeeding generations of Etruscans continued to speak Etruscan for hundreds of years, but some Etruscans, naturally, learned Latin as a second language; moreover, many children grew up bilingual in Etruscan and Latin," Pulju said. "Eventually, the social advantages of speaking Latin and having an identity as a Roman outweighed those of speaking and being Etruscan, so that over the generations, fewer and fewer children learned Etruscan." The end result is that the Etruscan language simply died.

Etruscan Language

Theresa Huntsman of Washington University in St. Louis wrote: “The Etruscan language is a unique, non-Indo-European outlier in the ancient Greco-Roman world. There are no known parent languages to Etruscan, nor are there any modern descendants, as Latin gradually replaced it, along with other Italic languages, as the Romans gradually took control of the Italian peninsula. The Roman emperor Claudius (r. 41–54 A.D.), however, took a great interest in Etruscan language and history. He knew how to speak and write the language, and even compiled a twenty-volume history of the people that, unfortunately, no longer exists today. [Source: Theresa Huntsman, Washington University in St. Louis, "Etruscan Language and Inscriptions", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

The Etruscans had a written languages but only fragments have been discovered. It was unlike any other language and to this day it remains undeciphered. About 10,000 Etruscans inscriptions have been found, most of them are tomb inscriptions related to funerals or dedicated to gods. They can be "read" in the sense that scholar can make out the specific letters, derived from Greek, but apart from about a few hundred names for places and gods they can not figure out what the inscriptions say.

In 1885 a stele carrying an inscription in a pre-Greek language was found on the island of Lemnos, and dated to about the 6th century B.C. Philologists agree that this has many similarities with the Etruscan language both in its form and structure and its vocabulary.

In 1964, archaeologists found three Rosseta-stone-like gold sheets with Etruscan writing and Phoenician writing in Pygi, Italy. The texts were determined to related to rituals but they failed to add much to the understanding of the Etruscan language. As of 2010, about 300 Etruscan words were known.

See Separate Article: ETRUSCAN'S UNUSUAL, MOSTLY-UNDECIPHERED LANGUAGE europe.factsanddetails.com

Evolution of the Latin Alphabet

The Romans devised the most widely used alphabet in the world today. Romans were reading the same upper case letters that we read today in 600 B.C. and developed lower case forms around A.D. 300. The only changes were made in the Middle Ages when the letter "J" (a consonant version of the letter "I") was added "V" was divided into "U," "V" and "W."

The Phoenician alphabet provided the basis for the Hebrew and Arabic alphabet as well as the Greek alphabet which gave birth to the Latin alphabet which beget the modern alphabet. The Phoenician alphabet had 22 letters, each for sound rather than a word or phrase. The Phoenician alphabet is the ancestor of all European and Middle Eastern alphabets as well as ones in India, Southeast Asia, Ethiopia and Korea. The English alphabet evolved from the Latin, Roman, Greek and ultimately the Phoenician alphabets. The letter "O" has not changed since it was adopted into the Phoenician alphabet in 1300 B.C.

Greek writing was passed on to the Etruscans who passed their writing on to the Romans. By the time the Romans were through little of the Greek alphabet was left. Like the Greek alphabet, the Latin alphabet had 24 letters, or signs. The Greek signs “z,” and “x” were dropped and then later placed at the end of the Latin alphabet. Some signs were added. Other signs were given different sounds. Others signs were changed. By the time all the changing was done the Latin alphabet had 26 letters and only about a half dozen vowels.

Initially there were no small letters, only capitals. There was a formal writing used for documents and flowing, cursive style used for informal writing.

Roman Inscriptions

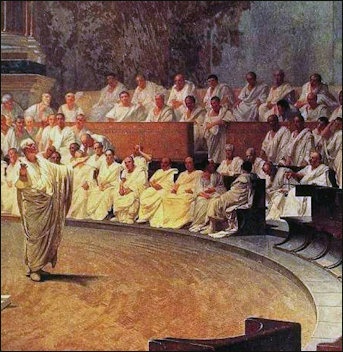

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In a number of civilizations, the written word has been seen as an art form in itself—calligraphy. One may, for example, see ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs or Arabic inscriptions as attractive and meaningful even without an understanding of their contents. In the classical world, the use of the Greek and Latin alphabets, derived originally from Phoenician characters, has been taken to be much more functional, and it is the reading of the surviving texts that has been regarded as all-important. There are many more extant examples of Roman inscriptions than earlier Greek and Hellenistic ones, but not all Roman inscriptions are in Latin. In fact, probably as many Roman inscriptions are in Greek as in Latin, for Greek was the common language in the eastern half of the empire, the other from Sardis in Asia Minor. .jpg)

inscriptions

In addition, many, principally official, inscriptions were put up in both languages. An example of a private bilingual inscription (in Latin and Greek) is the tombstone of a freedwoman (ex-slave) called Iulia Donata that forms part of the Cesnola Collection from Cyprus. Some Roman inscriptions, however, are written in other languages; there are examples of inscribed Palmyrene funerary stelae, dating from the second to third centuries A.D. Palmyrene is an ancient form of Aramaic. Many of these local languages eventually disappeared, but Hebrew, for example, continued to flourish during Roman times. [Source: Christopher Lightfoot, Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/insc/hd_insc.htm February 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Inscriptions are valuable historical documents, shedding light on the political, social, and economic realities of the past and speaking directly to the modern reader across time. Relatively few inscriptions survive from the Roman Republic; the vast majority belong to the Imperial period—that is, from the time of the first emperor Augustus (27 B.C.–14 A.D.) until the third century A.D. The number of inscriptions set up in the late Roman period (fourth–sixth century A.D.) was much reduced but still much larger than in the following early medieval period (the so-called Dark Age). It is impossible to estimate the number of surviving Roman inscriptions, although this must run into the hundreds of thousands, and, of course, archaeologists and chance finds are continually bringing yet more to light. This ever-growing corpus of epigraphical material provides information about many different aspects of life in the Roman world. The inscriptions are thus valuable historical documents, shedding light on the political, social, and economic realities of the past and speaking directly to the modern reader across time. \^/

“The variety of media used for inscriptions (stone, metal, pottery, mosaic, fresco, glass, wood, and papyrus) is matched by the diverse ways in which the inscriptions themselves were used. At one end of the scale were large, formal inscriptions such as dedications to the gods or emperors, publications of official documents such as imperial letters and decrees, and, on a smaller scale, the names and titles of rulers minted on coins along with their portraits or the discharge papers, known as military diplomata, of Roman soldiers that are found on portable bronze tablets. At the other end are casual inscriptions such as the graffiti that have been found on street walls at Pompeii and private correspondence such as the papyrus letter containing a mundane shopping list. \^/

“The largest group of Roman inscriptions comprises epitaphs on funerary monuments. The Romans often used such inscriptions to record very precise details about the deceased, such as their age, occupation, and life history. From this evidence, it is possible to build up a picture of the family and professional ties that bound Roman society together and allowed it to function. In addition, the language of Roman funerary texts demonstrates the human, compassionate side of the Roman psyche, for they frequently contain words of endearment and expressions of personal loss and grief. A good example of the various aspects of Roman funerary art is the marble funerary altar of Cominia Tyche. In addition to a fine portrait of the deceased, in which she is depicted with the elaborate hairstyle that was fashionable among the ladies of the imperial court in the late first century A.D., there is a Latin inscription that records her precise age at death as 27 years, 11 months, and 28 days. Furthermore, her grieving husband, a certain Lucius Annius Festus, wished her to be known as "his most chaste and loving wife," her qualities being emphasized by the use of superlatives in each case. \^/

“The most enduring legacy of Roman inscriptions, however, is not their content, regardless of how important that may be, but the lettering itself. For through the medium of carved inscriptions the Romans perfected the shape, composition, and symmetry of the Latin alphabet. Roman inscriptions thus became the model for all later writing in the Latin West, especially during the Renaissance, when the setting up of public inscriptions revived and the use of printing spread the written word farther than ever before. It was not just that the Latin language formed the basis of western European civilization, but it was also because the Latin alphabet was so clear, concise, and easy to read that it came to be adopted by many countries around the world. Those brought up in such a tradition perhaps find it hard to appreciate the beauty and grace of these letter forms, but at its best, as seen in innumerable ancient inscriptions in Rome and elsewhere around the ancient world, Latin may justly be described as calligraphy.

Writing Materials in Ancient Rome

For writing the Romans used different materials: first, the tablet (tabula), or a thin piece of board covered with wax, which was written upon with a sharp iron pencil (stylus); next, a kind of paper (charta) made from the plant called papyrus; and, finally, parchment (membrana) made from the skins of animals. The paper and parchment were written upon with a pen made of reed sharpened with a penknife, and ink made of a mixture of lampblack. When a book (liber) was written, the different pieces of paper or parchment were pasted together in a long sheet and rolled upon a round stick. When collected in a library (bibliotheca), the rolls were arranged upon shelves or in boxes. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

An iron stylus — a writing implement used to press letters into wax or clay tablets — dating to about A.D. 70 was unearthed from a trash dump of Londinium (Roman London) along a lost tributary of the Thames. It bears a personal message in Latin etched along its sides: “I have come from the City. I bring you a welcome gift with a sharp point that you may remember me. I ask, if fortune allowed, that I might be able (to give) as generously as the way is long (and) as my purse is empty.” The stylus is thought to have been a gift from a friend. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2019]

Usually only the upper surface of the sheet—formed by the horizontal layer of strips—was used for writing. These strips, which showed even after the process of manufacture, served to guide the pen of the writer. In the case of books where it was important to keep the number of lines constant to the page, lines were ruled with a circular piece of lead. The pen (calamus) was made of a reed brought to a point and cleft in the manner of a quill pen. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

For the black ink (atramentum) was occasionally substituted the liquid of the cuttlefish. Red ink was much used for headings, ornaments, and the like, and in pictures the inkstand is generally represented with two compartments, presumably one for black ink, one for red ink. The ink was more like paint than modern ink, and, when fresh, could be wiped off with a damp sponge. It could be washed off even when it had become dry and hard. To wash sheets in order to use them a second time was a mark of poverty or niggardliness, but the reverse side of schedae that had served their purpose was often used for scratch paper, especially in the schools.” |+|

Letters and Books in Ancient Rome

Letters were written on a wax-coated surface with a bone or metal stylus. Preserved items were written on parchment. Writing was done on papyrus or vellum with chiseled reed pens in the Mediterranean areas. In Britain it was done on wooden tablets with ink or carved with styluses. On other places people wrote on thin sheets of sapwood with styluses.

Roman books included picture puzzle books, military training manuals and wooden notebooks. The idea of pages didn't really take shape until the invention of parchment in the 2nd century. The Romans built great libraries with books they took from conquered territory and works they added themselves. By A.D. 350 there were 29 libraries in Rome. Literacy spread. The English historian Peter Salway has noted that England under Roman rule had a higher rate of literacy than any period until the 19th century.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN LITERATURE: CLASSICS, BOOKS AND THE BOOK MARKET europe.factsanddetails.com

Slave Shorthand from Ancient Rome

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Several years ago, Ryan Baumann, a digital humanities developer at Duke University, was leafing through an early 20th-century collection of ancient Greek manuscripts when he ran across an intriguing comment. The author noted that there was an undeciphered form of shorthand in the margins of a piece of papyrus and added a hopeful note that perhaps future scholars might be able to read it. The casual aside set Baumann off on a new journey to unlock the secrets of an ancient code. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 5, 2022]

Initially, Baumann told me, he thought that perhaps everything had been deciphered. “I thought to myself, ‘Well, it’s been about 100 years, maybe someone has figured it out!’ So, I looked into it, and to my delight, the system of ancient Greek shorthand does seem to have been largely figured out.” To his dismay, though, this century-spanning scholarly achievement has also been largely overlooked and underexplored. Very few people are interested in shorthand.

Why does this matter? Well, ancient Greek and Latin shorthand (also known as stenography or tachygraphy) were the bedrock of ancient writing and record keeping. The scripts that emerged in the first century B.C. allowed people to record things faster than “normal.” Just like today, said Baumann, stenography was “crucially important” for recording courtroom proceedings and political speeches, but dictation was also used to compose letters, philosophy, and narrative. Everything from ancient romance novels to foundational political theories were first transcribed in shorthand. Often this would have happened on erasable wax tablets (we have many examples from archaeological excavations), but shorthand was also used on papyri and parchment.

Though his primary training was in computer science, Baumann has been working with the Duke Collaboratory for Classics Computing since 2013 and on papyri since 2007. The Duke Collaboratory runs papyri.info, an open access online resource that gathers information about ancient Greek papyrus manuscripts and their contents. Duke is one of the foremost institutions in the world for working on ancient manuscripts — it not only has a remarkable collection, it is the home of numerous prominent manuscript experts. So, Baumann was in a position to think more about these ancient codes.

There are various different theories about where shorthand came from but most of the legends about its origins identify it as “slave knowledge.” Latin shorthand may have had its origins in Greek shorthand but the most popular theory, since the Christian writer Jerome in the fifth century, connects it to Tiro, the best known of the politician Cicero’s secretaries. According to tradition, it is Tiro who was responsible for inventing a multiple-thousand system of abbreviations — often referred to as Tironian Notes — that condensed spoken word into a terse system. There’s some evidence that elite authors thought shorthand was déclassé: Seneca described it as “slavish brands” devised by “the lowest quality slaves.”

Reading Scrolls

Mary Beard, a professor of classics at Cambridge University, wrote in the New York Times: The books Greeks and Romans read “were not “books” in our sense but, at least up to the second century. The “book rolls” “long strips of papyrus, rolled up on two wooden rods at either end. To read the work in question, you unrolled the papyrus from the left-hand rod, to the right, leaving a “page” stretched between the two. It was considered the height of bad manners to leave the text on the right hand rod when you had finished reading, so that the next reader had to rewind back to the beginning to find the title page, bad manners — but a common fault, no doubt, Some scribes helpfully repeated the title of the books a the very end, with just this problem in mind.”

“These cumbersome rolls made reading a very different experience than it is with the modern book,” Beard wrote. “Skimming, for example, was much more difficult, as looking back a few pages to check out the name you had forgotten (as it is on Kindle). Not to mention the fact that at some periods of Roman history, it was fashionable to copy a the text with no breaks between words, but as a river of letters. In comparison, deciphering the most challenging postmodern text (or “Finnegan’s Wake,” for that matter) looks easy.”

Bad Latin and Tattoos

Jack Malvern wrote in The Times: “The dead language has had a renaissance in tattoo parlours as people seek to emulate celebrities such as David Beckham and Angelina Jolie, but the yearning for classical language has come at a cost.David Butterfield, director of studies in classics at Queens' College, Cambridge, was delighted when he first noticed that Latin had become the lingua franca of skin decoration. He offered a translation service and supplemented his salary by charging small fees. However, he will announce in the next edition of Spectator Life magazine that he has decided ti stop, for fear of fuelling a terrible trend. [Source: Jack Malvern, The Times, March 28 2017]

.jpg)

“Although most people contracted him to ensure that their planned inscriptions were correct, Dr. Butterfield also had to let down gently those who were checking the ones they already had.

The lecturer, who has fielded about 1,500 inquiries since he began offering his services in 2007, said that although Latin lent gravitas, it was also tricky to get right. "When photographs were sent in for checking, it was often manifest that mistakes had been grafted in inch-high-letters," he said. "Latin is a language that leaves no wriggle room: when it is wrong, it is inescapably wrong, at best ungrammatical, atbworst gibberish."

“Asked whether he had to be diplomatic when telling people about indelible errors, he said: "It was never worthwhile beating unduly about the bush: if a woman has got a self-referential tattoo describing her in the gender of a man, that needs raising, howerver gently the news is passed on. I would give the most optimistic reading of how their Latin could be interpreted, perhaps suggesting that it would pass for a school-boy's Latin in medieval Castle."

“He noted that Beckham, who has ut amem et foveam (to love and cherish), had secured the correct translation, as had Jolie, whose belly is inscribed with quod me nutrit, me destruit (what nourishes me, destroys me). He said that many people had made the mistake of trusting online translation services. He saw one attempt to translate the biblical verse: "I walk through the valley of the shadow of death" that included English interspersed with the Latin: Ingredior per valley of umbra of nex. In other cases, a translation appeared to have been put through a spellchecker so that "Love is the essence of life" was not Amor est vitae essentia but "Amor est vital essentiaL"

Roman Names

Most Roman citizens had five names. The first three were like a surname, middle name, and last name. The last two usually revealed the person clan or place of origin. In ancient times people generally had only one name, which was given at birth. People with the same name were often differentiated from one another by identifying them as the son of someone (i.e. James, the son of Zeledee in the Bible) or linking them to their birthplace (i.e. Paul of Tarsus, also from the Bible).

The Romans developed surnames to link people with their family members and ancestors. With the fall of the Roman Empire, surnames disappeared until they were reappeared in the late Middle Ages. Romans liked names that began with the letter “C”: Caesar, Cicero, Cato, Claudius, Curio, Clodia, Clatulus, Catilibe, Caelius. C originally had the value of G and retains it in the abbreviations C and Cn. for Gaïus and Gnaeus. When they are Anglicized, these praenomina are often written with the C.

See Separate Article: NAMES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Vindolanda Tablets

In 1973 workers digging a drainage ditch at Vindolanda uncovered piles of Roman trash under a thick layer of clay. Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “The wet layer held everything from 1,900-year-old building timbers to cloth, wooden combs, leather shoes, and dog droppings, all preserved by the oxygen-free conditions. Digging deeper, excavators came across hundreds of fragile, wafer-thin wooden tablets covered in writing. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, September 2012 ]

These Vindolanda tablets were found mainly in a waterlogged rubbish heap at the corner of the fort commander's house. Dr More have been recovered from other parts of the site since. As of 2012, there were over 400 tablets, made of postcard-size pierces of wood between one and three millimeters thick. Letter writers wrote in ink before folding the leaf in half and writing the address on the back. In some cases, longer documents have been created by punching holes in the corner and tying several of these tablets together. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, November 16, 2012 |::|]

Adrian Goldsworthy wrote in National Geographic History:The trove held two types of tablets. One was a thin piece of wood covered in wax, which could be reused by melting the wax and smoothing it flat. While these sometimes preserve scratches made by the point of a stylus, the traces of successive messages often overlapped, creating a jumble of letters impossible to decipher. [Source Adrian Goldsworthy, National Geographic History, June 8, 2023]

The other type was meant for single use. Wood tablets were coated with only a thin layer of beeswax to prevent ink from spreading. Even in the case of the single-use tablets, the ink has often faded and become illegible. Sometimes scratches are visible, if only under a microscope or in an enlarged photograph. Sometimes there are just spaces, which means guessing how many letters might be missing and trying to deduce what the words might have been from the context. Deciphering the texts is a painstaking task, requiring an exhaustive knowledge of Latin—and all the slang and abbreviations employed by the Roman military.

See Separate Article: VINDOLANDA: ROMAN SOLDIER LIFE, TABLETS AND LETTERS europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024