ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S BIRTH

mosaic depicting the legendary birth of Alexander

Alexander was born in Pella, near the Aegean coast, on July 20, 356 B.C. to Philip II's forth wife Olmypias. He was taught warfare by his father, King Phillip II of Macedonia, religion by his mother Olympias and morality by Aristotle. His childhood was tough. He endured meals with little food and long marches. He excelled at everything he did, hung out with hard-drinking soldiers, horsemen and hunters and was inspired by Homer's tales.

Plutarch wrote: “Alexander was born the sixth of Hecatombaeon, which month the Macedonians call Lous, the same day that the temple of Diana at Ephesus was burnt; which Hegesias of Magnesia makes the occasion of a conceit, frigid enough to have stopped the conflagration. The temple, he says, took fire and was burnt while its mistress was absent, assisting at the birth of Alexander. And all the Eastern soothsayers who happened to be then at Ephesus, looking upon the ruin of this temple to be the forerunner of some other calamity, ran about the town, beating their faces, and crying that this day had brought forth something that would prove fatal and destructive to all Asia. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“Just after Philip had taken Potidaea, he received these three messages at one time, that Parmenio had overthrown the Illyrians in a great battle, that his race-horse had won the course at the Olympic games, and that his wife had given birth to Alexander; with which being naturally well pleased, as an addition to his satisfaction, he was assured by the diviners that a son, whose birth was accompanied with three such successes, could not fail of being invincible.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

ALEXANDER THE GREAT (356 TO 324 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S MARCH OF CONQUEST europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S APPEARANCE, CHARACTER, PERSONALITY AND HABITS factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S PERSONAL LIFE: WIVES, FRIENDS, LOVERS, CHILDREN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER BECOMES KING OF MACEDONIA AND THE ELIMINATION OF RIVALS AND THREATS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Philip II of Macedonia: Greater Than Alexander” by Richard A. Gabriel, Illustrated, (2010) Amazon.com;

“Philip II of Macedonia” by Ian Worthington (2010) Amazon.com;

“By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire” by Ian Worthington (2016) Amazon.com;

“Olympias: Mother of Alexander the Great” by Elizabeth D. Carney (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Daughter of Neoptolemus : A Biography of Olympias, the Mother of Alexander the Great” by Michael A. Dimitri (1993) Amazon.com;

"The Young Alexander: The Making of Alexander the Great" by Alex Rowson Amazon.com;

“Fire from Heaven” by Mary Renault (1969), Novel About Young Alexander, Amazon.com;

“Child of a Dream” by Valerio Massimo Manfredi (1998). Novel Amazon.com;

“Bucephalus: Warhorse of Alexander the Great” by Douglas A Dowell (2024), mainly for kids Amazon.com;

“The Horse in the Ancient World: From Bucephalus to the Hippodrome (Library of Classical Studies) by Carolyn Willekes (2016) Amazon.com;

“Rhetoric to Alexander” (Illustrated) by Aristotle and Aeterna Press (2015), of dubious origin Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Philip Freeman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Alexander of Macedon” by Peter Green (1974) Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Alexander” by Mary Renault (1975) Amazon.com;

Primary Sources:(Also available for free at MIT Classics, Gutenberg.org and other Internet sources):

“History of Alexander” by Quintus Curtius Rufus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica” by Arrian (Oxford World Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander” by Arrian Amazon.com;

“The Life of Alexander the Great” by Plutarch (Modern Library Classics) Amazon.com;

Philip II of Macedon, Alexander the Great’s Father

Philip II of Macedonia. Philip II of Macedon (reigned 359 to 336 B.C.), Alexander the Great's father, was the King of Macedonia and Olympias. He became king of Macedon in 359 B.C. at about the age of 23 and ruled for 23 years. An adept warrior, strategist and warrior, he transformed Macedonia from a loose confederation of tribes and cities into a powerful kingdom and introduced an agile cavalry and long pikes to warfare as he overhauled his army.

Philip II

Philip II was blinded by an enemy's arrow and was lamed in a battle. He enjoyed wine, lavish feasts and women. He had at least seven wives. Like many upper class Greek men, Philip was also reportedly a bisexual. He showed great courage in battle, was a shrewd politician and patronized the arts, filling his court with writers, artists, philosophers and actors.

Paul Halsall of Fordham University wrote: “Philip II of Macedon took a faction-rent, semi-civilized country of quarrelsome landed nobles and boorish peasants, and made it into an invincible military power. The conquests of Alexander the Great would have been impossible without the military power bequeathed him by his almost equally great father. At the very outset of his reign Philip had to confront sore perils in his own family and among the vassals of his decidedly primitive kingdom."

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the first half of the fourth century B.C., Greek poleis, or city-states, remained autonomous. As each polis tended to its own interests, frequent disputes and temporary alliances between rival factions resulted. In 360 B.C., an extraordinary individual, Philip II of Macedonia (northern Greece), came to power. In less than a decade, he had defeated most of Macedonia's neighboring enemies: the Illyrians and the Paionians to the west and northwest, and the Thracians to the north and northeast. Phillip II instituted far-reaching reforms at home and abroad. Innovations—improved catapults and siege machinery, as well as a new kind of infantry in which each soldier was equipped with an enormous pike known as a sarissa—placed his armies at the forefront of military technology. In 338 B.C., at the pivotal battle of Chaeronea in Boeotia, Philip II completed what was to be the last phase of his domination when he became the undisputed ruler of Greece. His plans for war against Asia were cut short when he was assassinated in 336 B.C. Excavations of the royal tombs at Vergina in northern Greece give a glimpse of the vibrant wall paintings and rich decorative arts produced for the Macedonian royal court, which had become the leading center of Greek culture." [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org]

For more on the battle See Separate Article: PHILIP II (ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S FATHER): HIS LIFE, LOVES, MURDER AND THE RISE OF MACEDON europe.factsanddetails.com

Olympias — Alexander the Great’s Mother

Olympias

Alexander was very close to his mother, Olympias, a princess from Epirus in northwest Greece. She was proud, strong-willed, superstitious, and religious. She boasted she was a member of the orgiastic, ecstatic Dionysus cult that specialized in handling snakes. Olympias could also be quite ruthless. After Phillip died she killed Philip's last wife Eurydice, and Eurydice's baby daughter, Europa “by dragging them over a bronze vessel filled with fire."

Olympias — Alexander the Great’s mother— was eldest daughter of Neoptolemus, king of Epirus, and the fourth wife of Philip II of Macedon. Her father claimed descent from Pyrrhus, son of Achilles. It is said that Philip fell in love with her in Samothrace, where they were both being initiated into the mysteries (Plutarch, Alexander, 2). The marriage took place in 359 B.C., shortly after Philip's accession, and Alexander was born in 356 B.C. She was extremely influential in Alexander's life and was recognized as de facto leader of Macedon during Alexander's conquests. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911; Wikipedia]

Philip III Arrhidaios — Alexander the Great's half-brother and successor — and his young warrior-queen wife Eurydice, were respectively killed and forced to commit suicide by Olympias. Additionally, Cleopatra, Philip II's last wife was either killed or forced to commit suicide by Olympias. .According to the 1st century AD biographer Plutarch, Olympias was a devout member of a orgiastic snake-worshiping cult of Dionysus, and he suggested that she slept with snakes in her bed.

Elizabeth Carney wrote in National Geographic History: Olympias was the first woman to participate actively in the political events of the Greek peninsula. Olympias as murderous, vengeful, and brave — much like her male kin — but history has not treated her as grandly. The violence of her husband and son, both responsible for hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of deaths, tends to be taken for granted — even celebrated — whereas both ancient and modern authors often fault Olympias, for not being nice. She wasn’t. But neither was Philip or Alexander. [Source: Elizabeth Carney, National Geographic History, December 4, 2019]

See Separate Article: OLYMPIAS — ALEXANDER’S THE GREAT'S MOTHER europe.factsanddetails.com

Alexander the Great’s Family Roots and His Father’s Vision

Plutarch wrote: “It is agreed on by all hands, that on the father's side, Alexander descended from Hercules by Caranus, and from Aeacus by Neoptolemus on the mother's side. His father Philip, being in Samothrace, when he was quite young, fell in love there with Olympias, in company with whom he was initiated in the religious ceremonies of the country, and her father and mother being both dead, soon after, with the consent of her brother, Arymbas, he married her. The night before the consummation of their marriage, she dreamed that a thunderbolt fell upon her body, which kindled a great fire, whose divided flames dispersed themselves all about, and then were extinguished. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

Alexander's family from the Nuremberg chronicles

“And Philip, some time after he was married, dreamt that he sealed up his wife's body with a seal, whose impression, as be fancied, was the figure of a lion. Some of the diviners interpreted this as a warning to Philip to look narrowly to his wife; but Aristander of Telmessus, considering how unusual it was to seal up anything that was empty, assured him the meaning of his dream was that the queen was with child of a boy, who would one day prove as stout and courageous as a lion. Once, moreover, a serpent was found lying by Olympias as she slept, which more than anything else, it is said, abated Philip's passion for her; and whether he feared her as an enchantress, or thought she had commerce with some god, and so looked on himself as excluded, he was ever after less fond of her conversation. Others say, that the women of this country having always been extremely addicted to the enthusiastic Orphic rites, and the wild worship of Bacchus (upon which account they were called Clodones, and Mimallones), imitated in many things the practices of the Edonian and Thracian women about Mount Haemus, from whom the word threskeuein seems to have been derived, as a special term for superfluous and over-curious forms of adoration; and that Olympias, zealously, affecting these fanatical and enthusiastic inspirations, to perform them with more barbaric dread, was wont in the dances proper to these ceremonies to have great tame serpents about her, which sometimes creeping out of the ivy in the mystic fans, sometimes winding themselves about the sacred spears, and the women's chaplets, made a spectacle which men could not look upon without terror.

“Philip, after this vision, sent Chaeron of Megalopolis to consult the oracle of Apollo at Delphi, by which he was commanded to perform sacrifice, and henceforth pay particular honour, above all other gods, to Ammon; and was told he should one day lose that eye with which he presumed to peep through that chink of the door, when he saw the god, under the form of a serpent, in the company of his wife. Eratosthenes says that Olympias, when she attended Alexander on his way to the army in his first expedition, told him the secret of his birth, and bade him behave himself with courage suitable to his divine extraction. Others again affirm that she wholly disclaimed any pretensions of the kind, and was wont to say, "When will Alexander leave off slandering me to Juno?"”

Alexander the Great as a Child

Plutarch wrote: “While he was yet very young, he entertained the ambassadors from the King of Persia, in the absence of his father, and entering much into conversation with them, gained so much upon them by his affability, and the questions he asked them, which were far from being childish or trifling (for he inquired of them the length of the ways, the nature of the road into inner Asia, the character of their king, how he carried himself to his enemies, and what forces he was able to bring into the field), that they were struck with admiration of him, and looked upon the ability so much famed of Philip to be nothing in comparison with the forwardness and high purpose that appeared thus early in his son. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“Whenever he heard Philip had taken any town of importance, or won any signal victory, instead of rejoicing at it altogether, he would tell his companions that his father would anticipate everything, and leave him and them no opportunities of performing great and illustrious actions. For being more bent upon action and glory than either upon pleasure or riches, he esteemed all that he should receive from his father as a diminution and prevention of his own future achievements; and would have chosen rather to succeed to a kingdom involved in troubles and wars, which would have afforded him frequent exercise of his courage, and a large field of honour, than to one already flourishing and settled, where his inheritance would be an inactive life, and the mere enjoyment of wealth and luxury.

“The care of his education, as it might be presumed, was committed to a great many attendants, preceptors, and teachers, over the whole of whom Leonidas, a near kinsman of Olympias, a man of an austere temper, presided, who did not indeed himself decline the name of what in reality is a noble and honourable office, but in general his dignity, and his near relationship, obtained him from other people the title of Alexander's foster-father and governor. But he who took upon him the actual place and style of his pedagogue was Lysimachus the Acarnanian, who, though he had nothing to recommend him, but his lucky fancy of calling himself Phoenix, Alexander Achilles and Philip Peleus, was therefore well enough esteemed, and ranked in the next degree after Leonidas.”

Olympias’s Upbringing of Alexander the Great

Olympia is thought to have spoiled Alexander royally and he idolized her in return. Richard Covington wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “From his father Alexander is believed to have inherited courage, quickness of decision and intellectual perceptiveness. His mother, who may have tried to turn their son against his father, gave him a will stronger than Philip’s, as well as fervent religiosity."

Elizabeth Carney wrote in National Geographic History: Since Philip was frequently absent on campaign, Olympias took on a greater role in raising her son, who probably knew his mother better than his father. Plutarch described Alexander’s relationship with Philip as competitive but affectionate. Philip treated Alexander like his heir. He left the 16-year-old in charge of Macedonia (with the assistance of his general Antipater) while Philip was off on campaign. [Source: Elizabeth Carney, National Geographic History, December 4, 2019]

Philip had only one other son (later known as Philip III Arrhidaeus) by another wife, and it became apparent that he was mentally disabled. Alexander appeared to be the likely heir, which made Olympias the most prestigious of Philip’s wives (there was no formalized chief wife). Since kings could have many sons and no formal rules for succession seem to have existed, mothers tended to become succession advocates for their sons, and Olympias became that for hers.[Source: Elizabeth Carney, National Geographic History, December 4, 2019]

By the end of his life, Alexander the Great was claiming that his real father was not Philip II of Macedonia, but the god Zeus. Alexander's desire to transcend the merely mortal echoes his mother’s belief in her family origins: According to the first-century A.D. historian Plutarch, Olympias told her son that he had been conceived when a thunderbolt — interpreted as Zeus — entered her womb. Alexander, by all accounts, went on to confirm it and took a highly dangerous journey across the Libyan desert during his invasion of Egypt. He visited the oracle of Ammon-Zeus at the remote oasis of Siwa, where a priest confirmed his divine parentage.

Alexander as a Youth

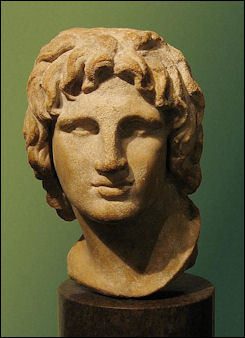

Alexander bust

Quintus Curtius Rufus wrote: By this time young Alexander was twelve years of Age, and began to take great delight in the feats of War, shewing most manifest signes of a Noble Heart, and an excellent apprehension. He was very swift of foot; and one day at a solemn game of Running, called The Olympic Race, being demanded by some of his Companions if he would run with them; Gladly, (said he) if there were Kings Sons to run with me. [Source: Quintus Curtius Rufus (Roman historian, probably A.D.1st century), “The Life and Death of Alexander the Great, King of Macedon,” translated by Robert Codrington (1602-1665), University of Michigan, Oxford University, 2007-10 quod.lib.umich.edu/]

As often as Tydings came that the King his Father had conquered any strong or rich Town, or obtained any notable Victory, he never seemed greatly joyful; but would say to his Play-Fellows, My Father doth so many great Acts, that he will leave no occasion of any remarkable thing for us to do: Such were his words, such was his talk: whereby it was easie to conjecture what a Man he would prove in his Age, who so began in his Youth. His delight was not set on any kinde of pleasure, or greediness of gain, but in the only exercise of Virtue, and desire of Honour: The more Authority that he received of his Father, the less he would seem to bear.

And although by the great increase of his Fathers Dominion, it seemed that he should have the less occasion of Wars; yet he did not set his delight in vain pleasure, or heaping up of treasure, but sought all the means he could to use the feats and exercises of War, coveting such a Kingdom, wherein for his Virtue and Prowess he might purchase Fame and Immortality. That hope never deceived Alexander, nor any other, that had either will or occasion to put the same in practise.

Alexander the Great Tames Bucephalus

When Alexander was twelve he mounted a wild horse that no one could break, causing Alexander's father to remark, "O my son, look out for a kingdom worthy of thyself, for Macedonia is not large enough to hold you." According to one story Alexander broke the horse after figuring out it reared when it saw its own shadow. Before he mounted him he calmly stroked the horse and pointed him towards the sun so he couldn't see his shadow. The horse, Bucephalas, was with Alexander on his march of conquest. When Bucephalas died at the age of 30 of battle wounds sustained fighting an elephant-mounted army in Pakistan he was given a royal funeral.

Alexander and Bucephalus

Plutarch wrote in “Life of Alexander”: “When Philonieus, the Thessalian, offered the horse named Bucephalus in sale to Philip [Alexander's father], at the price of thirteen talents, the king, with the prince and many others, went into the field to see some trial made of him. The horse appeared extremely vicious and unmanageable, and was so far from suffering himse lf to be mounted, that he would not bear to be spoken to, but turned fiercely on all the grooms. Philip was displeased at their bringing him so wild and ungovernable a horse, and bade them take him away. But Alexander, who had observed him well, said, "What a horse they are losing, for want of skill and spirit to manage him!" Philip at first took no notice of this, but, upon the prince's often repeating the same expression, and showing great uneasiness, said, "Young man, you find fault with your elders, as if you knew more than they, or could manage the horse better." "And I certainly could," answered the prince. "If you should not be able to ride him, what forfeiture will you submit to for your rashness?" "I will pay the price of the horse." [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46–120), “Life of Alexander,” John Langhorne and William Langhorne, eds., “Plutarch's Lives,” Translated from the Original Greek. Cincinatti: Applegate, Pounsford and Co., 1874, pp. 434-439]

“Upon this all the company laughed, but the king and prince agreeing as to the forfeiture, Alexander ran to the horse, and laying hold on the bridle, turned him to the sun; for he had observed, it seems, that the shadow which fell before the horse, and continually moved as he moved, greatly disturbed him. While his fierceness and fury abated, he kept speaking to him softly and stroking him; after which he gently let fall his mantle, leaped lightly upon his back, and got his seat very safe. Then, without pulling the reins too hard, or using either whip or spur, he set him a-going. As soon as he perceived his uneasiness abated, and that he wanted only to run, he put him in a full gallop, and pushed him on both with the voice and spur.

“Philip and all his court were in great distress for him at first, and a profound silence took place. But when the prince had turned him and brought him straight back, they all received him with loud acclamations, except his father, who wept for joy, and kissing him, said, "Seek another kingdom, my son, that may be worthy of thy abilities; for Macedonia is too small for thee..."

Aristotle and Alexander the Great

Aristotle tutored Alexander from age 13 to 16 beginning in 343 B.C., when Aristotle was in his early 40s. Up that time he had spent most of his life at Plato’s Academy in Athens. He was there from age 17 to 37. Aristotle left the Academy shortly after Plato died in 348 B.C. Aristotle lived until 322 B.C. This period in Athens, between 335 and 323 B.C., after teaching Alexander, is when Aristotle is believed to have composed many of his famous works.

Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “It was Philip’s idea" to hire Aristotle. "Alexander, was a bold, headstrong boy of unusual intelligence. There was a connection between the two families: Aristotle’s father had been a friend and court physician to Philip’s father, Amyntas III. There was also bad blood: Philip had razed Aristotle’s hometown of Stagira six years previously and sold most of its inhabitants into slavery. Nonetheless, the two men came to an agreement. Aristotle would instruct Alexander, and in return Philip would rebuild Stagira and resettle its citizens there. [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, June 2020]

Aristotle was well paid. Philip also helped Aristotle in his studies of nature by assigning gamekeepers to tag wild animals for him. After Alexander became king of Macedonia he gave Aristotle a lot of money so he could set up a school. While he was in Macedonia, Aristotle made friends with the general Antipater, who ran Macedonia while Alexander was on his campaign of conquest. The friendship was close enough that Antipater was the executor of Aristotle's will. Aristotle no doubt received some financial assistance from him as well.

Alexander had a deep love for Greek literature. He reportedly loved to recite passages from the plays of Euripides from memory. Plutarch wrote: "He regarded the Iliad as a handbook of the art of war and took with him on his campaigns a text annotated by Aristotle, which he always kept under his pillow together with a dagger." In the end Alexander proved more open minded than Aristotle, who tended to view non-Greeks as barbarians.

See Separate Article: ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND ARISTOTLE: TEACHING, INFLUENCES AND HOW THEY GOT TOGETHER europe.factsanddetails.com

Alexander Distinguishes Himself Early in Battle

from Philip II's tomb

The Battle of Chaeronea was fought in 338 B.C. near the city of Chaeronea in Boeotia, between Macedonia under Philip II and an alliance of city-states led by Athens and Thebes. The battle was the culmination of Philip's final campaigns in 339–338 BC and resulted in a decisive victory for the Macedonians and their allies. [Source Wikipedia]

The crucial phase of the Battle of Chaeronea was led by 18-year-old Alexander and his elite Companion cavalry unit. They found a break in the enemy line and went straight after the legendary crack Thebes unit, the Sacred Band, who had a reputation for fighting to the death of the last man and were buried, according to their code of honor, in a mass grave underneath a monumental lion.

Plutarch wrote: “While Philip went on his expedition against the Byzantines, he left Alexander, then sixteen years old, his lieutenant in Macedonia, committing the charge of his seal to him; who, not to sit idle, reduced the rebellious Maedi, and having taken their chief town by storm, drove out the barbarous inhabitants, and planting a colony of several nations in their room, called the place after his own name, Alexandropolis. At the battle of Chaeronea, which his father fought against the Grecians, he is said to have been the first man that charged the Thebans' sacred band. And even in my remembrance, there stood an old oak near the river Cephisus, which people called Alexander's oak, because his tent was pitched under it. And not far off are to be seen the graves of the Macedonians who fell in that battle. This early bravery made Philip so fond of him, that nothing pleased him more than to hear his subjects call himself their general and Alexander their king. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

For more on the battle See Separate Article: PHILIP II (ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S FATHER): HIS LIFE, LOVES, MURDER AND THE RISE OF MACEDON europe.factsanddetails.com

Alexander the Great Insulted By His Father

As for his father, Peter Green, a classic professor at the University of Texas, told Smithsonian magazine that Alexander and Philip II had a love-hate relationship marked by “an ambivalent blend of genuine admiration and underlying competitiveness." The fickleness of Philip and the jealous temper of Olympias led to a growing estrangement, which became complete when Philip married a new wife, Cleopatra, in 337 B.C. Alexander, who sided with his mother, withdrew, along with her, into Epirus, whence they both returned after the assassination of Philip, which Olympias is said to have countenanced. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911]

At the wedding between Philip and Cleopatra , the wine flowed freely for Philip and his guests. Elizabeth Carney wrote in National Geographic History: The uncle and guardian of the bride, a Macedonian general named Attalus, asked those assembled to join him in a toast that the new marriage might bring to birth a legitimate successor. Alexander sprang up enraged, demanded to know if Attalus was calling him a bastard, and threw a cup at him. Philip attempted to draw his sword on his own son and failed because he was so drunk he tripped, and Alexander mocked him. After this drunken brawl, Olympias and Alexander went back to Molossia.

Exactly what the drunken Attalus meant by his insult is unclear: He could have been charging Olympias with adultery or insinuating that Alexander, the son of a foreign woman, was therefore not legitimate. He simply could have meant that any child born of this new marriage to his niece would be more legitimate than Alexander. His exact meaning is difficult to ascertain, as is Philip’s reasoning for supporting Attalus’s very public insult of his current heir.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Alexander's birth, Flicker.com

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024