ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CITIES AND TOWNS

With few exceptions, villages, towns and cities were set up on the Nile, which was the main transportation route and the main source of water for drinking and agriculture. There were streets in the towns. They generally were not paved.

Cities and large towns had separate districts where glassware was produced, textiles were made, cattle were kept and pigs were slaughtered. The nicest neighborhoods were near the pharaoh’s or the governor’s palace. Agricultural fields were often mixed in with houses, which tended to clustered together so as not to waste land.

Large cities in the Near East in the third millennium B.C. had only around 20,000 people. Later they got bigger, Memphis, the capital for much of Egypt’s ancient history, covered 20 square miles at its largest in about 300 B.C. , with a population of around 250,000. Today most of it lies under the village of Mit Rahina and fields that surround it.

In towns and cities "granaries, breweries, carpenters and weavers shops were attached modular fashion to households." Smelly fish-processing and smokey bakeries were usually on the northwest, downwind side, of the households.

But unfortunately it is now almost impossible to form an exact picture of the appearance of an ancient Egyptian town, for nothing remains of the famous great cities of ancient Egypt except mounds — not even in Memphis nor in Thebes is there even the ruin of a house to be found, for later generations have ploughed up every foot of arable land for corn. The only ruins that remain are those of the city of Amarna, built for himself by the reformer Akhenaten, and destroyed by violence after his death; this city lay outside the arable country, and therefore it was not worth while to till the ground on which it had stood. We can still trace the broad street that ran the whole length of the town which was about 5.5 kilometers (three miles) long and 0.8 kilometers (half a mile) broad, and see that on either side of the street were large public buildings with courts and enclosures. It is impossible to trace how that part of the town occupied by the numerous small private buildings was laid out. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Towns and Cities” by Eric Uphill (2008) Amazon.com;

“Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province” by Naguib Kanawati and Alexandra Woods (2011) Amazon.com;

“Tell Dafana Reconsidered: The Archaeology of an Egyptian Frontier Town” by Francois Leclere and Jeffrey Spencer (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Cities of Ancient Egypt” by Steven R. Snape (2014) Amazon.com;

“Cities and Urbanism in Ancient Egypt” by Manfred Bietak, Ernst Cerny, Irene Forstner-Muller (2010) Amazon.com;

“Amarna: A Guide to the Ancient City of Akhetaten” by Anna Stevens (2021) Amazon.com;

“The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and Its People” by Barry Kemp Amazon.com;

“Thebes in Egypt: A Guide to the Tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor” by Nigel Strudwick (1999) Amazon.com;

“Abydos: Egypt's First Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris” by David O'Connor (2009) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Egyptian Urban Centers

Since the 1980s excavations have uncovered urban remains that have debunked conventional ideas that the Egypt of the pharaohs, in contrast to Mesopotamia, was somehow a civilization without cities. “We can now confirm that this was not the case,” Nadine Moeller, an Egyptologist at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, told the New York Times. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, July 1, 2008]

Moeller described the discovery of a large administration building and seven grain silos buried at the site of an ancient provincial capital on the Upper Nile. The partly preserved round silos, more than 3,500 years old, appear to be the largest storage bins known from early Egypt. Seal impressions and other artifacts associated with commodities put a somewhat older date for the central building, with at least 16 columns.

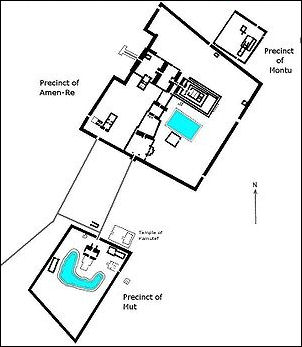

Karnak temple map “This is a really amazing site, at the cutting-edge of recent Egypt archaeology,” Stuart Tyson Smith of the University of California, Santa Barbara told the New York Times. “Digging into towns, you get the full range of life, not the very narrow view of society as seen from the top, from the rich and elite.” Mark Lehner, an Egyptologist who uncovered remains of settlements for workers who built the pyramids at Giza, said that at Dr. Moeller’s site he inspected layers of sediments showing occupation extending back 5,000 years to the dawn of Egyptian civilization and forward to the early Islamic period in the first millennium A.D. The silos are near temple ruins from about 300 B.C. “Where there are temples, we are learning, they were surrounded by towns which have usually been overlooked,” Dr. Lehner said.

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “The site of the recent discovery is at Tell Edfu, halfway between the modern cities of Aswan and Luxor (Thebes in antiquity). For much of Egyptian history, the central government was based in Memphis, in the north, or Thebes. The town at Tell Edfu was an important regional center with close ties to Thebes.Dr. Moeller and a team of European and Egyptian archaeologists began excavations near the temple there in 2005. They exposed a large courtyard surrounded by mud-brick walls. Underneath the courtyard, they came upon foundations of the first three of the seven silos. From artifacts, the archaeologists dated the silos to the 17th dynasty, 1630 to 1520 B.C.

These storage bins, presumably for barley and emmer wheat, which were used for food and as a medium of exchange, were built of mud brick, with diameters from 18 to 22 feet. If their height was greater than the diameter, as was the usual case, the silos probably stood at least 25 feet tall. “Their size was a surprise, nothing we had encountered before, certainly not in a town center,” Dr. Moeller said.

In the last three years, the team excavated the column bases and chambers of what they think was the town’s administrative center. The building layout suggests it may have been part of the governor’s palace, and artifacts mark it as the economic heart of town.

Seal impressions, which established the building’s existence in the 13th dynasty, 1773 to 1650 B.C., indicate their use in identifying different commodities. Some seals showed ornamental patterns of spirals and hieroglyphic symbols belonging to different officials. Archaeologists said this was evidence of the activities in the building like accounting and the opening and sealing of boxes and ceramic jars in the course of business transactions.

“The work at Edfu is important in that it allows us to examine ancient Egypt as an urban society,” said Gil Stein, director of the Oriental Institute. As a specialist in Mesopotamian archaeology, Dr. Stein noted the longstanding assumption that the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers was “a land of cities and Egypt was something else, because in Egypt we had not been looking at or for cities.”

Changing Location of Ancient Egyptian Royal Cities

It is probable that the great towns in ancient Egypt often changed their position, like the eastern towns of the Middle Ages. It was customary in the East that a mighty monarch should begin at his accession to “build a city; “he generally chose an outlying quarter of the town or a village near the capital as the site of his palace, and transferred to it the seat of his government. Occasionally this new place was permanent, but as a rule it was never finished, and disappeared a few generations later, after a successor had established a new residence for himself Thus the capital in the course of centuries moved hither and thither, and officially at least changed its name; this was the case with almost every great city of the East. A king might also choose a new plot of ground far from the capital without its becoming on that account more permanent. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

We know for certain that this was customary with the Pharaohs of the New Kingdom; Thebes was indeed maintained as the capital of the kingdom, on account of her great sanctuaries, but the king resided in some newly-founded city bearing the name of the founder. The new city was built “after the plan of Thebes “with granaries and storehouses, with gardens and tanks that it might be “sweet to live in," ' and the court poet sung of her glory in his “account of the victory of the lord of Egypt: “'

“His Majesty has built for himself a fortress, '

Great in victory' is her name.

She lies between Palestine and Egypt,

And is full of food and nourishment.

Her appearance is as On of the South,

And she shall endure like Memphis.

The sun rises in her horizon

And sets within her boundaries,'

All men forsake their towns

And settle in her western territory.

Amun dwells in the southern part, in the temple,

But Astarte dwells towards the setting of the sun,

And Wadjet on the northern sidc.

The fortress which is within her

Is like the horizon of heaven,

' Ramses beloved of Amun ' is god there,

And ' Mentu in the countries ' is speaker.

The ' Sun of the ruler ' is governor, he is gracious to Egypt,

And 'Favorite of Atum ' is prince, to whose dwelling all people go. "

In the same way we know that Amenemhat, a king of the Middle Kingdom, built a town for his residence in the Faiyum, and erected his pyramids close by. The last circumstance explains what otherwise would appear most strange.

We are accustomed to accept the Greek tradition that the kings of the pyramid age resided at Memphis, the city of the ancient temple of Ptah and of the famous citadel of the “white wall. " The temple of Ptah lay near the present village of Mitrahine, and the royal fortress must also have been in the same neighbourhood. If we go through the monuments of the Old Kingdom we see with astonishment that they never mention the town of Memphis.

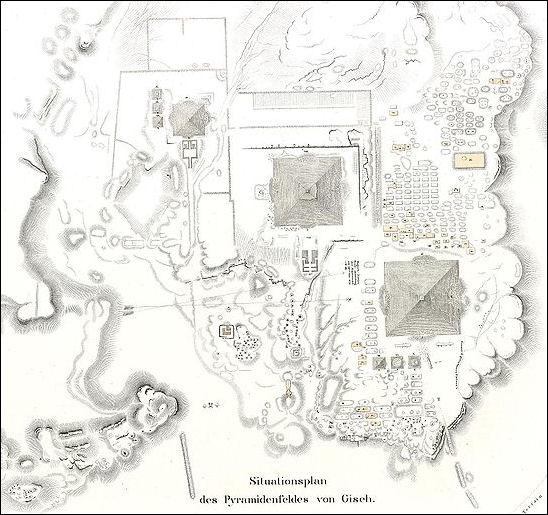

Pyramid layout near Memphis

Memphis

Memphis (18 miles southwest of Cairo) is oldest capital of ancient Egypt. Founded around 3000 B.C. by King Menes on land reclaimed from the Nile, it was selected as a site for the capital because it was located between Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt at a place where the Nile Valley narrows to less than a mile across, and travel between the northern and southern Egypt could be controlled.

Memphis was the capital for much of ancient Egypt’s history. The Great Pyramids of Giza are nearby. For a long time it was the administrative capital of the ancient Egyptian empire while Thebes was the religious center. The Pharaohs spent much of his time in Memphis and visited Thebes only during special religious ceremonies.

When Memphis was at its largest around 300 B.C. it covered 20 square miles and had a population of around 250,000. Today most of it lies under the village of Mit Rahina and fields that surround it. Memphis was once on the Nile but the now the river is some distance away. Nearly all of the great buildings that once stood in Memphis have been lost to time.

The original location of Memphis was probably different than its location later on. If we accept the general opinion that pyramid Pharaohs Khufu and Khafre resided at Memphis then we must also admit the strange fact that they built their tombs three miles from their capital, whilst the desert ground in the immediate neighbourhood was wholly bare of buildings. It is difficult to believe this; it is far more likely that the town of Khufu was in reality near his pyramid. The residence of Khafre and of Menkaure was also probably at Giza, that of the kings of the 5th dynasty at Abusir and to the north of Saqqara, whilst that of the Pharaohs of the 6th dynasty was close to the site of the later town of Memphis. In corroboration of this opinion we find that the oldest pyramid erected close to Memphis, the tomb of Pepi, was called Mennufer, the same name that Memphis bore later. The town of King Pepi probably bore the same name as his pyramid, and from that town the later town Mennufer — Memphis — was developed, which in the course of time grew to be a gigantic city with the famous temple, the “house of the image of Ptah," and the fortress of the “white wall. " Whilst the residences of the older kings have completely disappeared, leaving no trace except their pyramids, the residence of Pepi prospered on account of its vicinity to an important town. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The Memphis Museum contains a huge 30-foot-long reclining Colossus of Ramses the Great that weights 120 tons and is made of fine-grained limestone. Childless women still walk around the statue seven times in the belief it will make them pregnant. Some women reportedly have even climbed on statue and simulated the movements of love making. The Temple for Embalming the Sacred Apis Bull shows how to embalm a bull. Situated in a grove of palm trees is the Alabaster Sphinx of King Tuthmosis III. In the area is the necropolis of the Apis bulls (Serapeum), which contains 24 granite sarcophagi, each weighing over 60 tons.

Abydos in the New Kingdom

Abydos was another early city that declined and was reborn under Ahmose (1550-1525 B.C.) in the early New Kingdom. Cliffs around Abydos drops to the Nile flood plain and desert. New Kingdom sites include the remains of the last royal pyramid, built by Ahmose (1550-1525 B.C.), and remnants of a structures with scenes from Ahmose’s battle victories. In the a huge necropolis nearby archeologists discovered the Tablet of Abydos, which contains the names of Egyptian kings from Menes (the first great pharaoh) to Seti I. This long list of inscriptions helped scholars figure out the sequence of pharaohs starting with the first Egyptian kings.

The Temple of Seti I (1306-1290 B.C.) is one of the best preserved Pharaonic buildings in Egypt. Also known as El Balyana, it is painted and honors seven gods, including Orisis and the deified Seti I, and was constructed under Seti I and Ramses II. The Temple of Seti is best known for its detailed bas-reliefs and murals painted by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. The temple includes two hypostyle halls. The second one contains a forest of pillars and the best murals. A row of seven small chapels in the second hypostyle hall contains scenes of Seti I and various deities.

Abydos

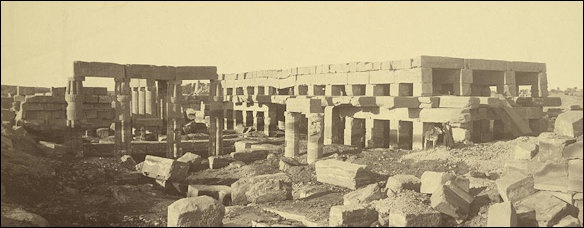

Thebes (Luxor): the Home of Ancient Egypt's Great Temples

Present-day Luxor (500 kilometers south of Cairo) was the site of ancient Thebes and is home to the greatest concentration of ancient monuments in Egypt: the magnificent temples of Karnak, Luxor and Hatshepsut , the Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens, the tomb of Tutankhamen, and the Colossi of Memnon, the giant broken statues of Ramses the Great that inspired Shelley's poem “Ozymandias”. From 2,100 to 750 B.C., Thebes was the religious capital of Pharonic Egypt and the center of Egyptian power. It embraced the area occupied by Karnak and Luxor. The priests who worked out of the temples became so powerful they were regarded as a threat to the pharaoh.

Thebes emerged as the main power center of Egypt at the dawn of the Middle Kingdom (2125 to 1520 B.C.) and became the capital of Egypt after the Hyksos were kicked out of Egypt. During the New Kingdom (1539 to 1075 B.C.) it was the center of Egypt. The pharaohs resided here and perhaps 1 million people lived in the area. The largest and most spectacular building were built during the reigns of Amenhotep III and Ramses II in the 14th and 13th century B.C. By Greco-Roman times it was already major tourist attraction. Pilgrims continued going to Karnak Temple to around A.D. 100.

Thebes (Waset, in ancient Egyptian) was the City of a Hundred Gates. It was the capital of Egypt beginning in the twelfth dynasty (1991 B.C.) and reached its zenith during the New Kingdom. Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “It was from here that Thutmose III planned his campaigns, Akhenaten first contemplated the nature of god, and Rameses II set out his ambitious building program. Only Memphis could compare in size and splendor but today there is nothing left of Memphis: It was pillaged for its masonry to build new cities and little remains. Although the mud-brick houses and palaces of Thebes have disappeared, its stone temples have survived.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Elaine Sullivan of UCLA wrote: “The ancient city of Thebes (or Waset as it was known in Egyptian) played an important role in Egyptian history, alternately serving as a major political and religious center. The city’s tombs, including those in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, are located on the west bank of the Nile, in the area’s limestone cliffs. The mortuary temples of many of the New Kingdom kings edge the flood plain of the Nile. The houses and workshops of the ancient Thebans were primarily located on the river’s east bank. Little remains of the ancient settlement, as it is covered by the modern city of Luxor. A series of important temples, composing the religious heart of Thebes, constitutes most of what remains today. To the south, close to the banks of the Nile, lies the Temple of Luxor. To the north, joined to Luxor by a sphinx- lined avenue, stand the temples of Karnak. Karnak can be divided into four sections: south Karnak, with its temple of the goddess Mut; east Karnak, the location of a temple to the Aten; north Karnak, the site of the temple of the god Montu; and main/central Karnak, with its temple to the god Amun-Ra.” [Source: Elaine Sullivan, UCLA, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Deir el-Medina lies on the western bank of the Nile, across from Luxor. According to Live Science: Beginning in 1922, around the same time that King Tut's tomb was found, the site was excavated by a French team. Known in the New Kingdom period as Set-Ma'at ("Place of Truth"), this was a planned community, a large neighborhood with rectangular gridded streets and housing for the workers responsible for building tombs for the Egyptian rulers. While the men would leave for days at a time to work on the tombs, women and children lived in the village of Deir el-Medina. An important feature of the site is the so-called Great Pit, an ancient dump full of pay stubs, receipts and letters on papyrus that have helped archaeologists better understand the lives of the common people. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science November 14, 2022]

Amara West, a Typical Ancient Egyptian Town

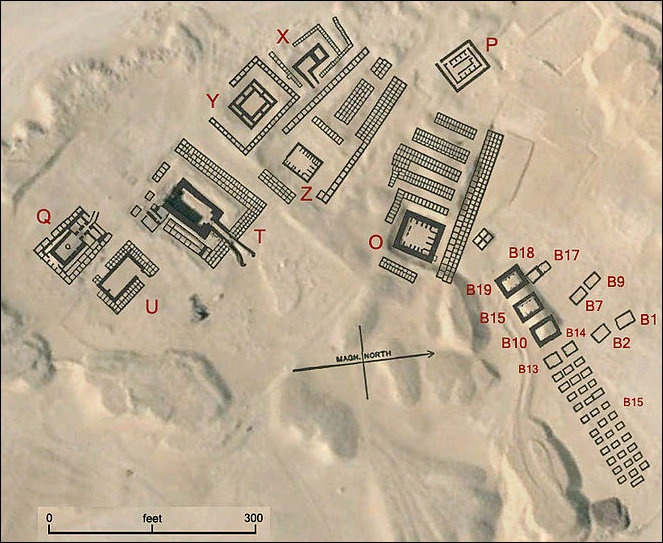

Amara West in present-day northern Sudan is a town of modest size compared to the royal residence towns of Tell el-Amarna or Qantir in Egypt proper, and once stood on an island in the Nile as it flows eastwards. According to the British Museum: “ A mudbrick town wall was built in the reign of Seti I, as shown by bricks bearing his stamped cartouche, measuring around 100m on each side. Three gates provided entrance to the town, the northeastern one leading into the stone cult temple. Perhaps commenced under Seti I, the decoration was undertaken under later kings, most notably Ramses II, Merenptah and near the end of Egyptian control of the area, Ramses IX. [Source: British Museum =]

“The temple, built from poor quality local sandstone is of typical plan for this era, with three cult chapels at the rear. It remains preserved, buried underneath spoil from the excavations of the 1940s, and at some point will require new epigraphic recording. The remainder of the walled town comprised densely packed mudbrick buildings, including large-scale storage, housing of varying grandeur (from 50 to 500m²) and structures of unclear function. =

“The Egypt Exploration Society excavators identified four phases of architecture, thought to span the 19th and 20th dynasties. The magnetometry survey of 2008 revealed the hitherto unknown western suburb, with a series of large villas. One of these was excavated in 2009, and featured rooms for large-scale grain-processing and bread cooking, as well as private areas with brick-paved floors and whitewashed walls. Near the southeastern corner of this building, we uncovered the remains of a circular building of unclear purpose, whose architecture clearly falls within a Nubian, not pharaonic, tradition, and thus might reflect the ethnic diversity of the population at Amara West. Further excavation in the western suburb in 2013 and 2014 has revealed additional villas and mid-sized houses, built over extensive rubbish deposits and probable garden plots. =

“There are few signs of Ramesside period buildings elsewhere on the island, although a group of small chapels and other buildings excavated by the EES outside the east wall of the town may hint at further suburb buried beneath the sand. Otherwise, much of the land was probably perfect for small-scale agricultural use, given the rich alluvial deposits left on its banks by the Nile channel each year.” =

Amarna

Amarna (Akhetaten, Tell el-Amarna)

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “Tell el-Amarna is the site of the late 18th Dynasty royal city of Akhetaten, the most extensively studied settlement from ancient Egypt. It is located on the Nile River around 300 kilometers south of Cairo, almost exactly halfway between the ancient cities of Memphis and Thebes, within what was the 15th Upper Egyptian nome. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Founded by the “monotheistic” king Akhenaten in around 1347 BCE as the cult center for the solar god, the Aten, the city was home to the royal court and a population of some 20,000-50,000 people. It was a virgin foundation, built on land that had neither been occupied by a substantial settlement nor dedicated to another god before. And it was famously short-lived, being largely abandoned shortly after Akhenaten’s death, some 12 years after its foundation, during the reign of Tutankhaten; a small settlement probably remained in the south of the city. Parts of the site were reoccupied during late antique times and are settled today, but archaeologists have nonetheless been able to obtain large expo sures of the 18th Dynasty city. Excavation and survey has taken place at Amarna on and off for over a century, and annually since 19.

See Separate Article: AMARNA: LAYOUT, BUILDINGS, AREAS, HOUSES, INFRASTRUCTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

Heliopolis — Ancient Egypt’s Mecca

For more than two millennia, Heliopolis was the center of Egyptian religion. Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: Ancient Egyptians believed the world began on a low hill just outside modern-day Cairo. There the sun rose for the first time and made order out of a roiling sea of elemental chaos. There the Egyptian creator, Atum, and sun god, Ra, first appeared, and there they held court for millennia. And there the Egyptians built their most enduring sacred site, a city known today by its Greek name, Heliopolis, or City of the Sun. At the center of the city, contemporaneous sources and recent archaeological excavations show, was the Temple of the Sun. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2019]

Heliopolitan Scheme and the Origin of Egypt’s First Gods, See ANCIENT EGYPTIAN RELIGION africame.factsanddetails.com and ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CREATION GODS AND MYTHS africame.factsanddetails.com

“Egyptians worshipped at Heliopolis over the course of countless lifetimes and thousands of years. The earliest known temples there date back nearly 4,600 years, to the first days of Egypt’s pyramids. Inscriptions reveal that generations of pharaohs bolstered their claim to have descended from Atum and Ra by building grand shrines there. At its peak around 1200 B. C. , the holy site was marked with dozens of colossal obelisks.

“Heliopolis was known far and wide in antiquity. Called On in Hebrew, the city is mentioned multiple times in the Old Testament. It also served as a reference point for other Egyptian sacred sites. Although Thebes, Egypt’s capital during the Middle and New Kingdoms (ca. 2030–1070 B. C. ), is now far better known, ancient Egyptian sources referred to it as the “Heliopolis of the South,” and its temples were modeled on those at Heliopolis. Even in its final centuries, Heliopolis was a popular destination supposedly visited by the Greek philosopher Plato, according to an account written four centuries later by the geographer and historian Strabo. Strabo also includes a first-person account of his own visit to the site’s nearly deserted ruins in his book Geographica.

“Both physically and theologically, Heliopolis was at the heart of Egyptian religion. It was both city and temple, every corner of it holy, but also filled with everyday activity. “You can compare it to the very center of Vatican City,” says archaeologist and University of Leipzig Egyptian Museum curator Dietrich Raue. “Everyone inside the city was somehow connected to the sun cult or temple. ”

“Yet today, Heliopolis is virtually unknown. After almost two and a half millennia of continuous worship there, the importance of its temples declined. By the second century B. C. , the city was abandoned, for reasons archaeologists are still trying to discern. It was subsequently plundered and stripped of anything that could be burned or reused. Beginning in the late Roman period, nearly all of its limestone architecture was carted away to build Cairo, leaving little to see above the surface. Over time, most of the city’s obelisks were removed, carried off first to decorate Alexandria, and then to Rome, Paris, London, and even New York. Only one still stands at the center of the site, a 68-foot-tall red granite monument erected by Senwosret I around 1950 B. C. that juts out of the ground in the impoverished Cairo neighborhood of Matariya like a hieroglyph-inscribed spike.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Eternal City” by Andrew Curry in Archaeology magazine archaeology.org

Important Towns in Upper (Southern) Egypt

The capital of this first province of Egypt was not Aswan, but the neighbouring town of 'Abu Simbel ("ivory town", Greek Elephantine). To the island on which this town was situated the Nubians of old brought the ivory obtained in their elephant hunts, in order to exchange it for the products of Egypt. Even in Roman times this town was important for commerce, as the place where the custom duties were paid. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Twenty-eight miles farther to the north on the east bank was the town of Kom Ombo, where stood the sanctuary of the crocodile god Sobek, and 14 miles beyond lay Chenu, the old Gebel Silsila at the point where the sandstone hills narrow the bed of the river before giving place to the limestone. Like Aswan, Gebel Silsila was important because of the great quarries close to the town. Gebel Silsila was the easiest point from Memphis or Thebes, where hard stone was to be obtained; and here were quarried those gigantic blocks of sandstone which we still admire in the ruins of the Egyptian temples.

Whilst the “land in front," or the first province, owed its importance to the quarries and to trade, that of the second province, called “the exaltation of Horus," was, as the name signifies, purely religious. Horus, in the form of the winged disk, here obtained his first victory over Set, and here therefore was built the chief sanctuary of this god. The present temple of Edfu is still dedicated to him; it is in good preservation and stands on the site of the ancient Debhot, but a building of Ptolemaic time has taken the place of the sanctuary erected by the old kings.

In the third nome, the shield of which bore the head-dress of the ram-headed god Khnum, two towns are worthy of mention: 1) Esna, the religious centre, where, as at Edfu, a late temple occupies the site of the old building; and 2) the town of Elkab, few towns have played such a leading part in Egypt as this great fortress, the governors of which during their time of office were equal in rank with the princes of the blood. Elkab was also important for the worship of the patron goddess of the south, Nekhbet, sometimes represented as a vulture, sometimes as a snake. Numerous inscriptions by pilgrims testify to the honour in which this goddess was held in old times, and even the Greeks resorted to Elkab in order to pray to her.

Karnak festival Hall

Karnak Settlements

Marie Millet of the Louvre and Aurélia Masson of the British Museum wrote: “At Karnak, in addition to the well known temples, there is another type of architecture: the settlements, “comprised mainly of mud brick buildings. “They are a testimony of the everyday life of the ancient Egyptians for which remains have been found throughout all of the temples of Karnak. Continuous occupation from the First Intermediate Period until the Late Roman Period is well attested at different locations in the complex of Karnak. Settlements are easily recognizable by their use of brick, especially mud-brick. The artifacts and organic remains found during new excavations of settlements give us a good idea of the inhabitants and their daily life. [Source: Marie Millet of the Louvre and Aurélia Masson of the British Museum, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Karnak is understood as the whole area occupied by the three temenoi: Montu, Amun-Ra, and Mut—by extension all of the current archaeological area. The notion of settlements can be defined by the construction material, the mud-brick, which was used for several types of buildings such as houses, workshops, and storehouses. .. We can find as many settlements outside the religious complex as inside. There are two categories of settlements, either they are associated with the town of Thebes (with regard to the “city of Thebes”) or they are linked to some institutional installations, cultic and royal (warehouses, workshops, priests’ houses, palaces, etc.). Both types can be found within the same settlement and, as they can show the same kind of architecture, it is sometimes hard to distinguish them. In the analysis of Karnak settlements, it would be helpful to erase the actual precinct walls to understand the topography throughout the evolution of the site .

“The southwest sector of the Amun Temple, which corresponds to the area of the Opet and Khons Temples and to the courtyard between the ninth and tenth pylons, was used for cultic activities from the middle of the 18th Dynasty until the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.). However, between the Middle Kingdom and the beginning of the 18th Dynasty, and later during the Roman and the Late Roman Periods, the architecture was civilian in nature. This was confirmed by excavations in the courtyard of the tenth pylon. Recently, excavations in front of the Opet Temple have provided new evidence for a settlement. A residential or artisanal quarter occupied this sector until the 13th Dynasty. Later it seems to have been associated with cultic buildings.”

See Separate Article: KARNAK TEMPLE: ARCHITECTURE, COMPONENTS, SETTLEMENTS, DECORATIONS AND GREAT HYPOSTYLE HALL africame.factsanddetails.com

Large Ancient Egyptian Town in the Middle of the Desert

A relatively large 218-acre town site at the end of an ancient road was found at the Kharga Oasis, a string of well-watered areas in a 60-mile-long north-south depression in the limestone plateau that spreads across the desert. John Noble Wilford wrote in New York Times, The oasis is at the terminus of the ancient Girga Road from Thebes and its intersection with other roads from the north and the south. A decade ago, the Darnells spotted hints of an outpost from the time of Persian rule in the sixth century B.C. at the oasis in the vicinity of a temple. “A temple wouldn’t be where it was if this area hadn’t been of some strategic importance,” Ms. Darnell, also trained in Egyptology, said in an interview. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, September 6, 2010]

Then she began picking up pieces of pottery predating the temple. Some ceramics were imports from the Nile Valley or as far away as Nubia, south of Egypt, but many were local products. Evidence of “really large-scale ceramic production,” Ms. Darnell noted, “is something you wouldn’t find unless there was a settlement here with a permanent population, not just seasonal and temporary.” It was in 2005 that the Darnells and their team began collecting the evidence that they were on to an important discovery: remains of mud-brick walls, grindstones, baking ovens and heaps of fire ash and broken bread molds.

Describing the half-ton of bakery artifacts that has been collected, as well as signs of a military garrison, Dr. Darnell said the settlement was “baking enough bread to feed an army, literally.” This inspired the name for the site, Umm Mawagir. The Arabic phrase means “mother of bread molds.”

In addition, Dr. Darnell said, the team found traces of what is probably an administrative building, grain silos, storerooms and artisan workshops and the foundations of many unidentified structures. The inhabitants, probably a few thousand people, presumably grew their own grain, and the variety of pottery attested to trade relations over a wide region. Umm Mawagir’s heyday apparently extended from 1650 B.C. to 1550 B.C., nearly a thousand years after the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza and another thousand before any previously known major occupation at Kharga Oasis.

“Now we know there’s something big at Kharga, and it’s really exciting,” Dr. Darnell said. “The desert was not a no man’s land, not the wild west. It was wild, but it wasn’t disorganized. If you wanted to engage in trade in the western desert, you had to deal with the people at Kharga Oasis.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024