ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DANCE

The ancient Egyptians were a dance-loving people. Dancers were commonly depicted on murals, tomb paintings and temple engravings. Ideographs show a man dancing to represent joy and happiness. Pictorial representations and written records from as early as 3000 B.C. are offered as evidence that dance has a long history in the Nile kingdom. According to the “International Encyclopedia of Dance”, “dance was part of the Egyptian ethos and featured prominently in religious ritual and ceremony on social occasions and in Egyptian funerary practices regarding the afterlife.”The study of ancient Egyptian dance is based mostly on identifying dance scenes from monuments, temples and tombs and translating and interpreting the inscriptions and texts that accompanied them. [Source: “ International Encyclopedia of Dance”, editor Jeane Cohen]

According to the “International Encyclopedia of Dance”, dances were performed “for magical purposes, rites of passage, to induce states ecstacy or trance, mime; as homage; honor entertainment and even for erotic purposes.” Dances were performed both inside and outside; by individuals pair but mostly by groups at both sacred and secular occasions.

Dance rhythms were provided by hand clapping, finger snapping, tambourines, drums and body slapping. Musicians played flutes, harps, lyres and clarinets, Vocalizations included songs, cries, choruses and rhythmic noises. Dancers often wore bells on their fingers. They performed nude, and in loincloths, flowing transparent robes and skirts of various shapes and sizes. Dancers often wore a lot of make-up, jewelry and had strange hairdos with beads, balls or cone-shaped tufts, Accessories included boomerangs and gavel-headed sticks. “ Ab” , the hieroglyph for heart, was a dancing figure.

The oldest depictions of dance comes from pottery from the predynastic period (4000 to 3200 B.C.) from the Naqada Ii culture that depicts female figures (perhaps goddesses or priestesses) dancing with upraised arms. Similar dancers are joined by men brandishing clappers in what is thought to represent mourners in a funeral procession. Some scholars believed that ballet moves such as the pirouette and arabesque originated in ancient Egypt.

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität wrote: “According to the Egyptian iconographical and textual sources, dance is performed by animals, human beings (dwarfs, men, women, and children appear in the reliefs), the bas of Pe, the deceased king or individual, the living king in a divine role, and gods and goddesses...According to ancient Egyptian sources, contexts in which dance occurs spontaneously, or is performed according to traditional ideas, include sunrise, banquets, funerals, the afterlife, joyousness, royal ceremonies, and religious festivals. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The most common noun for “dance” is jbAw, which was used continuously from as early as the Old Kingdom, where it is found in the Pyramid Texts, through the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.), where we find it featured in temple inscriptions. The determinative of the verb, and of the corresponding noun (“dancer”), is a man standing on one leg with the other leg bent at the knee. Nevertheless, the iconographical sources show both male and female dancers, and in a variety of contexts.

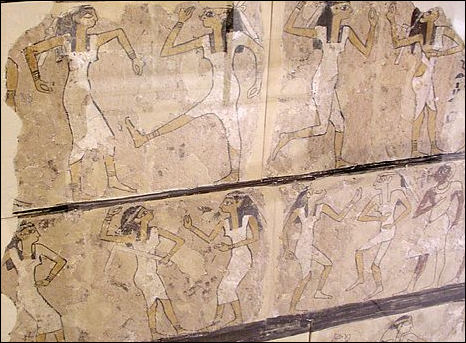

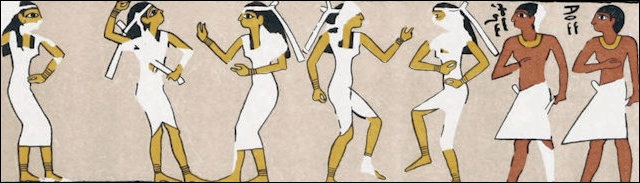

Without exception dancers who appear in pairs or groups are of the same gender. Their representation is abundant on reliefs and wall paintings in the tombs of private individuals from the Old Kingdom to the end of the New Kingdom. Dancers of non-Egyptian origin are a prominent feature in processions of the 18th Dynasty. A Ramesside ostracon bears a satirical illustration of dance. Textual sources for dance in religious ritual dominate in the Ptolemaic temples.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Dances” by Irena Lexová (1999) Amazon.com;

“Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2010) Amazon.com;

““Music and Musicians in Ancient Egypt” by Lise Manniche (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Music of the Most Ancient Nations - Particularly of the Assyrians, Egyptians and Hebrews” by Carl Engel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Love Poetry and Songs from the Ancient Egyptians” by Gilbert Moore (2015)

Amazon.com;

Hymns, Prayers and Songs: An Anthology of Ancient Egyptian Lyric Poetry”

by Susan Tower Hollis and John L Foster (1996) Amazon.com;

“Meditation Music of Ancient Egypt” by Gerald Jay Markoe (CD) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Festivals of Opet, the Valley, and the New Year: Their Socio-Religious Functions”

by Masashi Fukaya (2020) Amazon.com;

“Reliefs and Inscriptions at Luxor Temple, Volume 1: The Festival Procession of Opet in the Colonnade Hall” (1994) Amazon.com;

Types of Dance in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians word for dance was “in”. Types of dances for which there were specific words including striding dance (“hbi”), the acrobatic dance (“ksks”), the leaping dance (“trf “) and the pair dance.

Dances were performed at births, marriages, funerals, royal functions and ceremonies for the gods. Reliefs and murals depict, children, men, women, dwarfs, pygmies, kings, queens, animals such as baboons and ostriches and gods like Thoth, Horus, Isis and Isis all dancing. Hathor was the mistress of dance. Divine dwarfs performed the “dance of the gods.” Professional dancers were either priests or slaves who performed in temples or the homes of wealthy people. Priests performed dances in private called the "dance of the stars” in which the dancers moved from east to west across symbols of the planets and stars. There is evidence of dance instructions for girls as well as female dancers being members of the harems of kings and high officials.

dancing dwarf

Dances are thought to have been part of harvest festivals in which peasant sacrificed the first fruits to Min the god of Koptos and festivals of the great goddesses of pleasure Hathor and Bastet. In one dance, dancers held two short sticks in their hands. In one image of the harvest in the Old Kingdom wc see the workmen taking part in this dance, quick movements clapping their sticks together. Dancers were at the “Feast of Eternity" — that is the feast held in honour of the deceased; in fact the procession accompanying the statue of the deceased was generally headed by dancers. The accompanying plate shows us a feast of this kind. The girls, wearing nothing but girdles, stand close to the wreathed wine jars; they go through their twists and turns, clapping their hands to keep in time. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Sacred dances were directed to the goddesses — namely Hathor but also to Isis and Mut — and gods — particularly Amun but also to Min (god of fertility) and Maontus (god of war). These dances were featured in the Festival of the Erection of Djed and the month-long Opet Festival. There were dances to honor the king when he received foreign dignitaries and dances performed in association with the harvest and post circumcision initiation rites. There were also combat dances and dance to entertain the king and queen.

The mirror dance from the Old Kingdom featured four dancers organized in pairs “capturing the hand of Hathor” when the clappers clash. One boomerang dance featured young nude girls holding boomerangs organized in two concentric circles running in opposite directions. There were also special stick dances for boomerang-carrying men and one for dwarves.

The divine “god dance” performed by dwarves was greatly loved. If dwarves weren’t available chondrodystrophic cripples were used. Grotesque dwarf-figure toys and figures have been discovered. The dwarf gods Aha and Bes figure as musicians and singers in reliefs of royalist rituals. There is also some evidence that foreign “exotic” dancers — namely Libyans and Nubians — were in demand,. There are images of scantily-clad, black-skinned dancers at celebrations marking the arrival of the divine barks at Karnak. Libyan dancers are pictured doing a boomerang hunting dance with phallic shapes and ostrich feathers in their hair.

Egyptian Dance In Different Periods

In the Old Kingdom the dances tended to be formal and restrained. In the Middle Kingdom leaps and stamping were introduced. In the New Kingdom dancing became more graceful and fluid.

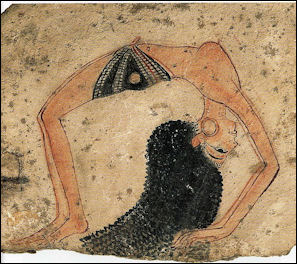

There are many depictions of dances from the Old Kingdom but the depiction vary little. The dances were usually performed by women or young girls. One early dance for which there are images shows a group dance by women with their arms raised above their head. Accompaniment is provided by women clapping and perhaps calling out. Some dancers performed in the nude and had unique ball-shaped hair styles. Pair dances, featuring men and women holding hands, are associated most with funerals. Images of women in loinclothes and braids doing deep backbend, high kicks and other precarious postures are thought to have been of acrobatic dancers or even erotic ones.

Middle Kingdom dances included acrobatic Hathor dances in which dancers laid on their stomachs are reached backs until their heads touched their feet; erotic danced by skirted quartets of young girls representing the union of the Sun god Ra with Hathor (“the mistresses of the sky”); large group dances with many men and women held in conjunction with funeral processions. Dances in reliefs and murals show men doing pirouettes and women mimicking the effects of the wind with their hands. One intriguing scene shows a man doing a squatting “Russian style” dance. Finger snapping was added to the array of rhythmic sounds.

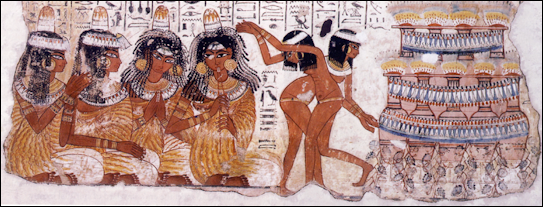

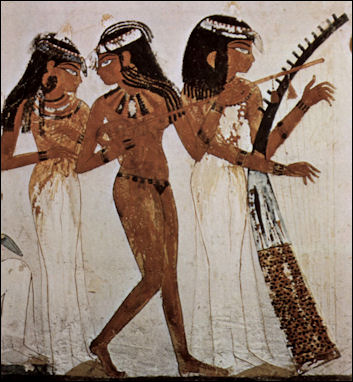

In the New Kingdom period dance scene show up frequently in banquet scenes and depict dance as much more joyous endeavor. Magdeg Saleh wrote in “International Encyclopedia of Dance”: “These charming scenes are radiant with clarity, harmony, grace, elegance and refinement — especially evident in the figures — fluid, sinuous curves and relaxed flow. They portray dancer-musicians in long, filmy gowns, delicately affecting head, arm, torso or leg gestures while playing the lute, flute, double oboe, lyre or tambourine...Many dancers are girls, very young and nude...some of them black. Movements are concentrated mainly on the upper body. Occasionally, clappers are used...One notable scene is interpreted as a belly dance, exalting fertility.”

In the New Kingdom acrobatic dances featured cartwheels and forward flips. Funeral dances featured robed and naked women banging on tambourines in an agitated way and thrusting forward their torsos. A Greek guest at a royal banquet in Memphis wrote: "two dancers, a man and a woman, went among the crowd and beat out the rhythm. Then each danced a solo veiled dance. Then they danced together, meeting and separating, then converging in successive harmonious movements. The young man's face and movements expressed his desire for the girl, while the girl continually attempted to escape him, rejecting his amorous advances. The whole performance was harmoniously coordinated, animated yet graceful, and in every way pleasing."

Tomb of the Dancers

Difficulty of Studying Ancient Egyptian Dance

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität wrote: “ “The study of dance in ancient Egypt presents problems of classification, representation, and interpretation. We do not possess sufficient information to construct a typology of dance in terms of distinctive movements and rhythms. Although 18 different verbs for “to dance” are attested according to the references given in the Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae, the terminology applied to dance escapes our comprehension, and the association between terms and selected movements is often obscure. Only a few names for body postures are attested. Extant artifacts (figurines in a dance posture) are sparse. The “frozen” postures and gestures depicted on reliefs do not allow for the reconstruction of a dancer’s movements or the composition and tempo of those movements. Nonetheless, some scholars have tried to deduce dance movements from gestures and body postures seen in Egyptian representations of dance. Postures have been interpreted as the dancer’s successive steps in a dance sequence, as if the artist tried to catch a certain moment of the performance, sometimes choosing to depict the extreme position of a movement, the body bent back, the legs spread in a split, and the arms stretched to the utmost. Ultimately, whether dance movements should be understood as synchronic or diachronic representations of actions remains an unsolved problem. According to pictorial representations, dancers were configured either in linear relationships—that is, dancing toward each other in opposite rows— or in pairs. Solo dancers are rarely depicted. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Aspects of tempo and rhythm are not easily interpreted. Textual “commentary” can sometimes be enlightening. In the tomb chapel of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan, for instance, the text adjoining a representation of dancers reads “wind”. Comments like this may indicate that the dance movements portrayed were performed with speed. An important aspect in regard to rhythm is the concept of “chironomy”—a memory aid through which rhythm is reflected by hand movements that count the beat. In the Old Kingdom clapping and percussion instruments were used to set the beat. In the New Kingdom, when there appears to have been a greater variety of instruments, new types of rhythm instruments may have influenced the beat and the tempo of a performance.

“The uncertain connection between dance and music renders the interpretation of reliefs and paintings difficult. In representations before the 18th Dynasty the dancers are not integrated in musical scenes; rather, they are depicted in a separate register. It is therefore not evident whether their dance is actually accompanied by the instrumental music. Even in depictions in which a musician is shown with a dancer, it is not clear whether the musician accompanies the dancer (musically) or whether the two are engaged in a dialog.

“The intended purpose of the representation of dance and its interdependence with the history of religion and the history of art complicates the exploration of developments in dance. The function of an image might have been that of a “picture-act” operating as a virtual performance. In a religious context, it appears that certain, select dance movements were typically displayed in the iconography. However, artistic conventions might have rendered the depicted body postures less concurrent with reality. Junker points out that, in the Giza mastaba of Kaiemankh, it is in accordance with artistic conventions for the expression of formal events that the musicians are depicted standing instead of sitting on the floor. In addition to their operationality as picture-acts, representations can be understood in an art-historical context—that is, in terms of their dependency on earlier or contemporary representations with regard to theme, composition, and style. These factors of “interpictoriality” are well demonstrated in the artistic development of the wall paintings in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.) tombs of Beni Hassan and in the Theban tombs from the time of Amenhotep II.”

Artifacts and Texts Associated with Dance in Ancient Egypt

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität wrote: “Artifacts associated with dance have survived as ceremonial objects and as gifts for the tomb owner. These valued objects possessed several layers of meaning. While musical instruments, dresses, mirrors, jewelry, headgear, ribbons, braid-weights, boomerangs, and sticks might be endowed with meaning based on their commissioning and design, the materials used in their production, methods of their use, and even possibly the professional experience of the associated musicians, they revealed symbolic performance-related power when employed in a dance context. This is especially clear with regard to multifunctional objects and parts of the human body. Hair, for example, appears to have taken on additional meaning when associated with dance, as is underscored by amagical text, according to which “the one who dances without hair” must suffer at the place of the crocodile (i.e., suffer a terrible fate). [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Literary evidence that the same complexity of meaning was valid for ceremonial objects is provided by the story of the birth of the royal children in Papyrus Westcar. In this narrative, a group of gods in the guise of traveling dancers reached the house where the royal children were to be born. There “they held out [to the distraught landlord] their necklaces and sistra.” Having thereby assured the landlord of their competence as midwives they were allowed to enter.

“A meaningful discussion of dance in ancient Egypt must include not only its consideration as an art form and as it is displayed in representations, but also its exploration in context, as performance. Common to the bulk of iconographical and textual sources for dance is its ritual significance. Dance is embodied knowledge, communicated and acted out by being performed as a dance. The particular dance executed is dependent upon the situation, and the dance is performed in relation to another person. Conceptualized as a ritual practice, dance can be characterized as the setting up of relationships between symbols by means of physical operations.”

Earliest Images of Ancient Egyptian Dance: Animals, Humans and Dwarves

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität wrote: “According to the Egyptian iconographical and textual sources, dance is performed by animals, human beings (dwarfs, men, women, and children appear in the reliefs), the bas of Pe, the deceased king or individual, the living king in a divine role, and gods and goddesses. Iconographical evidence for dancing animals appears during the 18th Dynasty. In the first hour of the Amduat, dancing apes (carrying strong religious power) welcome the sun god at sunrise and sunset. The imagined space that the animals create by jumping for joy at sunrise is the eastern horizon. At sunset, when the god enters the West, the apes are depicted dancing on a sandy terrestrial domain. On a satirical ostracon from Deir el-Medina a goat dances while a hyena plays the double oboe. Here, the animals represent human beings and shape a gendered “sensual” space. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Nebamun tomb fresco dancers and musicians

“The earliest known examples of a dancing human being come from the Badarian phase in plastic or incised decoration. In these examples ritual dancing is expressed by a typical posture: the arms are lifted upwards with incurving hands. According to Manniche the same position of hands and arms occurs in African fertility dances. It has been suggested that this posture represents a cow’s horns in a festive performance. The motif reached its peak during the Naqada II phase, where it is exhibited in clay figurines and on pottery vessels painted in the white cross-lined style. In the second half of the fourth millennium B.C. the motif is rare; more frequently seen are depictions of a dancer and musicians surrounded by boats, flora, and water-birds, indicating the Nilotic landscape.

“The dancing dwarf is situated in a multiplicity of contexts, the best known of which is a royal setting. Three dancers with braided hair depicted on an Early Dynastic macehead from Hierakonpolis resemble dwarfs. One of them holds a heart (jb) in his left hand. Morenz has suggested that this depiction is a cryptographic writing of “dance” (jbAw). The king depicted on the macehead implies a performance in a royal scenario. According to the Pyramid Texts, the deceased king dances in front of the throne in the role of the dwarf as “Dancer of God” (jbAw nTr). A dwarf who cheers up the king by dancing is also attested in the well-known letter of Pepy II to the governor of Elephantine, Harkhuf. Dancing dwarfs who entertain by comedic means are inserted in dance scenes in the mastabas of private individuals in Giza. A girl’s tomb in el-Lisht contained ivory carvings of nude dwarfs who could be turned either to the right or left on a game board. Masked representations of the god Bes carrying a tambourine or a pair of knives perform apotropaic dances. The dwarf Djeho who lived in the 30th Dynasty mentions on his sarcophagus dances that he performed on the occasion of religious festivals to honor Apis- Osiris and Osiris-Mnevis. According to Dasen the dwarf owes his role to his physical abnormality, which is not regarded as a deficiency but rather as a divine mark. In ancient Egypt the concept of divine as “generative,” or sometimes “dangerous,” is used to formulate borderlands. In a ritual environment, dwarfs bringing regeneration and repelling evil may explain their appearance in the role of “Dancer of God,” as burlesque actors, and as apotropaic dancers, shaping and protecting liminal spaces.”

Images of Dancers in Ancient Egyptian Tombs

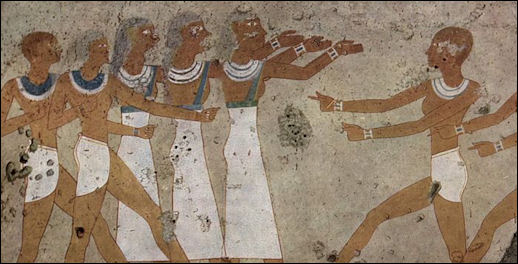

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität wrote: “From the 4th Dynasty to the end of the New Kingdom, dancers depicted in tombs of private individuals figure in three different contexts: the funerary rites, the banquet scenes, and the cult of Hathor. In reliefs and wall paintings of the funeral, they appear in the capacity of mourners and muu-dancers in processions accompanying the transport of the statue. Muu-dancers, recognizable by their papyrus-stalk garland or reed-crown, personify “the bas of Pe.” They are always male. From the 18th Dynasty on they are depicted without such headdresses. They are commonly shown with both fists placed on their chest (a gesture of veneration), with two fingers pointing to the ground, holding hands, or touching each other with one finger while holding the other hand straight. Dancing in groups of three, or in pairs, the muu hurry to meet the coffin (with its escort), follow it, and safeguard its journey. According to Altenmüller they function as “ferrymen” for the deceased. A passage in Sinuhe reads: “. . . with oxen dragging you and singers going before you. The dance of the Oblivious ones [the Muu] will be done at the mouth of your tomb- chamber”. It has also been proposed that the muu serve as guardians of liminal space. Performing in the necropolis as the bas of Pe, the muu- dancers come from the realm of the deceased forefathers. The imagined space they create can be defined as the (liminal) passageway leading in both directions from the realm of the living to that of the forefathers. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

dancing dwarf with a large penis

“In Old Kingdom scenes in the cult chambers of the mastabas from Saqqara, Dahshur, and Giza, dancers are shown in a row with both arms raised above their heads. Offering bearers are depicted in the same manner. To identify dancers in this formation and to distinguish them from offering bearers, the heel of the moving leg lifted from the ground is a reliable indicator. This standardized depiction of dancers appears first in representations from the 5th Dynasty. Already in the 6th Dynasty more extensive and varied body postures are portrayed. Occasionally a nude girl joins the dancing. Titles inform us about the social group of female dancers: “The singing by the harem (xnr) to the dance”. The dancers are subordinated to an overseer who can be either male or female. Sometimes the dancers are singing or playing musical instruments such as clappers, cymbals, drums, flutes, tambourines, and later even stringed instruments. Clapping hands, rattling jewelry, or snapping fingers indicate the rhythm. The costumes of the dancers change depending on the context and the fashion of the time. A short kilt and a garment of crossed bands that were knotted in the back were popular from the 5th to the end of the 6th Dynasty. In the 6th Dynasty pair-dancing appears. Van Lepp has interpreted its depicted gestures and body postures as the enacting of the funerary rites through dance In rites of passage the dance shapes a transitional space.

“The Coffin Texts articulate the idea that the deceased continue their existence among the living and may even dance among them: “Let him sing and dance and receive ornaments. Let him play draughts with those who are on earth, may his voice be heard even though he is not seen; let him go to his house and inspect his children for ever and ever”. Representations of dancing are requisite in banquet scenes. Kampp-Seyfried points out a shift in emphasis that took place toward the end of the 18th Dynasty: from this time onward, the living ones join the banquets of the deceased. Over time the representation of dancers in banquet scenes becomes increasingly detailed. In the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) female dancers are shown scantily dressed—perhaps wearing only a slim belt around their hips, bracelets, anklets, and sometimes a diaphanous robe. Their hair is long and loose, topped by a cone of ointment.”

Dance, Religion and Emotion in Ancient Egypt

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität wrote: “In Old, Middle, and New Kingdom tomb representations a dance with leaps and splits was performed by male or female dancers to honor the goddess Hathor. Scenes of this dance in the 6th Dynasty mastaba of Ankhmahor, for example, depict dancers who wear a long braid ending in a round weight. The latter consists of a ring or, as Hickmann has assumed, perhaps a rattling clay ball. In early representations the dancers hold clappers and a mirror. Later the broad collar and its counterpoise became the signifying attributes in the cultic dance for Hathor, such as we see in a representation in the Theban tomb of the vizier Antefoker. The inscription above the dancers who are positioned before the deceased’s wife Senet reads: “The doors of heaven are open. Behold, ‘The Golden One’ has come!”. The ritual objects used in the dance for Hathor produce the imagined space of a face-to-face encounter with the goddess. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Middle Kingdom literature and biographies testify to dance inspired by emotion. The protagonists in these examples are male. After Sinuhe has received good news from the king, who has just granted him permission to be buried in Egypt, he spontaneously performs a dance of joy: “I roved round my camp, shouting”, the 12th Dynasty Governor of Elephantine, Sarenput I, expresses joy about his promotion: “I danced like the stars of the sky”. He goes on to further highlight the interconnectedness of dancing and rejoicing: “My town was in a festive mood, my young people jubilating when the dancing was heard”. Two personifications of towns are depicted in the Karnak Temple, dancing in front of Thutmose III, who celebrates the “Feast of the White Hippopotamus”. In the Amarna tomb of Meryra II, jubilating and dancing men, women, and children celebrate the recipient of great honors upon his return to his house. On the pillars that flank the entrance to the mammisi of Edfu, a hymn of joy ends: “May the young women jubilate for him by dancing. Kamutef is his name”.”

“Gods emerge as dancers in the inscriptions from Late Period temples. A pillar fragment from the Ptolemaic mammisi of Edfu shows a newborn, unnamed god dancing on a lotus flower. On a Ptolemaic-Roman lintel in Dendara, the seven “Hathors” play the tambourine before Hathor and her son Ihi. The fifth of them is specified as “Hathor, Mistress of Kom el-Hisn, foremost of the place of inebriation [Dendara], Mistress of Dance,” and the seventh of them “dances for The Golden One”. In the pronaos of Dendara, Ihy himself bears the epithet “The one who dances for his mother”, and Hathor is the one “for whom the gods perform the jbAw- dance and for whom goddesses and musicians dance” Hathor-Tefnut herself dances in her temple at Philae, while the king dances for her in the role of Shu. A unique iconographic testimony to the king as performer is a depiction of the Roman emperor Trajan dancing for the goddess Menhyt-Nebtuu. The imagined space the gods create by dancing in the seclusion of the temples is their own ontological realm, the realm of the divine.

“According to Spell 835 from the Coffin Texts, “the deceased is promised power over gods who will serve him and not dance—that is, not be occupied with dance but instead be ready to serve the deceased. Magical papyri provide evidence for religious concepts associated with dancing. For example, in order to help a sick child, a magician draws an analogy to the dancing child-god Horus.”

Dance and Religious Festivals in Ancient Egypt

Erika Meyer-Dietrich of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität wrote: “Priests and priestesses, foreigners, gods, and the king in a divine role dance as celebrants in religious festivals. The instruments they carry were owned by the temple. The rank of such ceremonial dancers was apparently high. Eighth Dynasty king Neferkauhor appointed the second son of the vizier Shemai as a celebrant in order to dance and celebrate hymns before the god Min at Koptos. The most reported events at which ceremonial dance was performed were seasonal and religious festivals. In the Theban tomb of Kheruef, dancers at the Sed Festival of Amenhotep III are shown bent forward. Significantly, the text above the dancers links the dancing to mythological concepts of harvesting. [Source: Erika Meyer-Dietrich, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

dancer in an Ancient Egyptian costume

“From the time of Hatshepsut, dancers appear in the Opet-procession. They dance bent backward while entering Luxor Temple (south wall, 3rd reg). According to Wild the dancers belong to the temple of Amun. Temple personnel in priestly garments are frequently depicted as musicians and chironomists. In the scholarly discourse on dance in ancient Egypt their activity as dancers is subsumed under the heading “musicians.” The dance performed at festivals by Egyptian dancers required physical training and religious knowledge, because the dance expressed mythological acts and religious concepts. Possibly, the dancers were hired for the occasion or belonged to alternating groups of officiants. Ptolemaic-Roman papyri allow us our first glimpse of the working conditions of contracted dancers. Papyrus Cornell 26 informs us about the number of days a particular performance lasted and the date of the performance, as well as the payment, the condition, and the transport of professional dancers.

“Foreign dancers are attested as early as the Middle Kingdom. In the 18th Dynasty depictions of female Nubian dancers in a marshy environment appear on decorated objects, such as flute containers and spoons, as gifts for the New Year. At the same time male Nubians and Libyans are visible in representations of rituals performed in public venues. In the Opet-procession , these male dancers dance along the riverbank, accompanying the divine barque of Amun on its journey to Luxor. They are also part of the entourage in a Ptolemaic hymn that celebrates the goddess Hathor upon her return from her journey to Nubia. The text from the temple at Medamud praises Hathor, the returning “Eye of the Sun,” as “The Golden Goddess who is pleased by dances at night.” It begins: “Come, oh Golden One, who eats of praise, because the food of her desire is dancing”. The imagined space created by the dancers coming from the south is the far southeast region at dawn.

“Herodotus’ description of pilgrims on their way to Bubastis illustrates that the act of playing the flute and dancing, paired with raucous banter and the women’s exposure of their private parts, actually serves to define the route of the pilgrimage as a gendered liminal space.”

Theater and Drama in Ancient Egypt

Robyn Gillam of York University in Toronto wrote: “Drama is to be understood as a subset of performance involving verbal and physical interaction between two or more persons. Finding evidence for this activity in ancient Egyptian sources is challenging, but not without results. Dramatic texts appear to cluster between the 26th Dynasty and the Roman Period up to the second century CE and may point to the influence of Hellenic culture. [Source:Robyn Gillam, York University, Toronto, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Textual materials, as well as some archaeological remains, provide evidence for the existence of a full range of different types of performance throughout Egyptian Pharaonic culture. Performance may be defined as any activity acted out by embodied subjects before witnesses and is a form of behavior found in all human societies. It can range from a simple social interaction to a highly structured routine and encompass everything from playful or entertaining activities to highly portentous, effective ritual programs.

“Egyptian documents that show the best evidence for performances of dramatic characters are almost all connected with or part of ritual routines. Some of these routines appear not to involve interaction between two actors but between one actor and a statue or between one actor or actors and a dead body. From a modern perspective, these do not qualify as dramas, but it must be remembered that to the Egyptians, both statues and mummies could possess full subjectivity. It may also be argued that singers, readers, and storytellers “performed” literary, religious, and poetic texts for their listeners; but in the almost total absence of any direct evidence as to how this was achieved, they must be omitted from this discussion of dramatic material.”

Tomb of the Dancers dancers

Problems Defining and Finding Evidence of Ancient Egyptian Drama

Robyn Gillam of York University in Toronto wrote: “From our own culturally specific perspective, drama, a subset of performance, may be defined in a number of ways. A standard definition is that of a situation in which there is a conflict or interaction between two or more characters, which is resolved; and, by extension, any pre- structured or scripted situation where role- playing individuals take up these agonisticpositions. Early Greek theater, the only such form in the ancient Mediterranean world that is well documented and present for some of the same time period as Egyptian culture, made use of a protagonist (joined later by a deuteragonist and a tritagonist) and chorus. It involved the development of an argument (both in the sense of propositions and subject matter) relating to gods and heroes. Ethnographic evidence shows that similar forms have existed in other cultures , although there is almost no direct evidence for this kind of activity in Pharaonic Egypt. [Source: Robyn Gillam, York University, Toronto, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The best evidence for drama in the Egyptian record should demonstrate the presence of dialogue between living persons role-playing various characters in a situation deploying a narrative that is advanced by their interactions. Ideally, some kind of audience would be involved, but direct evidence for this is seldom forthcoming, except in the case of some processional festivals or public royal ceremonies. Unfortunately, the detection of drama in Egyptian sources relies on the discernment of some or (rarely) all of these criteria as well as the judgment of the individual researcher about the nature and purpose of the source.

“Poor rates of preservation for written documents in all but the later periods, as well as the restriction of writing to a minority literate class, mean that evidence for the more social, casual types of performance is extremely limited. Papyri originating from the New Kingdom workmen’s village at Deir el-Medina suggest the existence of staged political demonstrations, and assorted monumental and documentary sources point to the existence of work related performances such as those connected with the moving of large statues and blocks of stone . More indications can be found in the songs of laborers recorded in Old and Middle Kingdom tombs.

“Most evidence for Egyptian performance relates to highly structured ritual routines performed by and for the elite in connection with the installation and appearance of the king and the cult of the gods in formal temples. Such routines include the Sed (or Renewal) Festival, the appearance or coronation of the king, a variety of execration rites performed for the king and the gods, as well as the daily cult of the gods in their temples, the elaborate rites performed at royal and elite funerals such as the “Butite Burial”, the mummification ritual, and the Rite of Opening of the Mouth, which is aimed at ensouling cult and funerary images. While all such routines contain mythological allusions and often indicate that participants are to role-play various gods, any mythological narrative remains peripheral to their ritual or magically effective character, and the actions performed are mechanical rather than interactive. Furthermore, many of these ritual routines were performed in secret by highly trained, initiated practitioners.”

Activities That Might Qualify as Ancient Egyptian Drama

Robyn Gillam of York University in Toronto wrote: “There is, however, extremely limited evidence that dramatic performance, as defined above, may have existed in Egyptian culture. The Late Middle Kingdom Ramesseum Dramatic Papyrus preserves in tabular form a record of a divine narrative pertaining to the conflict of Horus and Seth, divided up into a series of sections in which protagonists are given dialogue. There are also sporadic indications of settings and props. Schematic drawings and labels seem to show that high ranking court officials role-play these characters. Very similar, but somewhat simpler in layout and design, is the much later text on the left side of the Shabaqo Stone. Eleven tableaux found on the inside of the outer wall of the temple of Horus at Edfu also present the same myth, combining pictures of the gods, dialogue, and narrative as in the Ramesseum Papyrus. “They also indicate the role of the king, royal children, and various priests in this routine. Although the dramatic character of this document has been questioned the recent identification of a Demotic text presenting dialogue and action for characters from the same myth makes it likely that narrative-based performances with interaction between characters existed. [Source: Robyn Gillam, York University, Toronto, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Tomb of the Dancers dancers

“Evidence for the selection of persons to play roles involving some kind of action and speech is indicated by the practice of selecting pre-pubescent girls to play the roles of the djeryt or “kites”, Isis and Nephthys, in mourning over their brother Osiris at state funerals and at the vigil for Osiris in the month of Khoiak, as celebrated in the later periods. While the role fulfilled by these young women is arguably of a ritual nature, it does have some dramatic aspects. The speeches and actions of these actors are recorded in the Bremner-Rhind Papyrus from the c. fourth century B.C. and are also indicated in the texts and representations in the Osirian chapels at Dendara of the mid first century B.C.. The Greek Serapeum Papyri of the second century B.C. indicate the high prestige and remuneration attached to the position of twin sisters who played this role at the funeral of the Apis bull.

“While almost all of this material relates to the myth of Horus and Seth, an inherently agonistic narrative, a Roman Period text from Esna relates to the birth of the divine king, as recorded in earlier texts and representations found in New Kingdom temples and Ptolemaic birth houses. This work does not include any pictures or explicit stage directions and has been put together from texts found in different parts of the temple by Serge Sauneron to include long, poetic speeches by the divine child and the gods who have created him and bestowed upon him divine attributes. Their speeches are interspersed with equally poetic hymns, which not only exalt the gods but comment on their actions. Sauneron’s reconstruction has been criticized, but the clear interactivity of the speeches of the characters makes its dramatic character hard to deny, even if there is no evidence for its application. The existence of utterances in the first person plural in the Edfu text as well as the reflexive character of the Esna hymns suggest the presence of a chorus and raise issues about the relationship of Egyptian dramatic performances to Greek theater, which can be attested in Egypt from the early Ptolemaic Period.

“Another significant element in this conclusion can be drawn from a comparison of the speeches of the characters in the Edfu and Esna texts with those in the Ramesseum Papyrus and on the Shabaqo Stone. The latter are so short and pithy as to not always be easily distinguishable from stage directions, while the former, especially the Esna texts, feature long, poetic passages that both apostrophize the gods and describe their actions and significance with vivid images and elaborate figures of speech. Although the content and imagery remain purely Egyptian, the stylistic features of these speeches may recall the works of Euripides, ever popular among the Greek-speaking community of Egypt, and even, especially in the case of Esna, the dense imagistic and rhetorical style of Silver Age Latin verse.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024