ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUSIC

3.jpg)

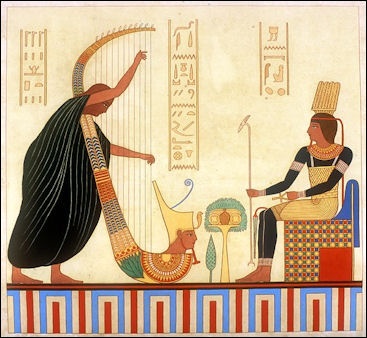

Harper playing before Shu Visitors to ancient Egypt often wrote about the abundance of music, dance, storytelling and songs in the kingdom and described feasts and ceremonies with musicians playing harps, lyres, tambourines, sistrums, “ mizmaar” (a reed flute), drums, lutes, cymbals and flutes. How Egyptian music sounded is not known.

Tomb paintings show musicians playing various instruments. One shows four women, thought to be professional entertainers, playing a harp, a lute, oboes and a lyre. The women appear to be dancing while they are playing. A small sculpture shows a musician kneeling as he plays a harp. Tomb paintings show the development of harps from something that resembled a hunter's bow to elaborate carved triangular instruments that resembled some kinds of modern harps.

Music was a key element in Egyptian religion. Some scholars believe it aimed to soothe the gods and encourage them to provide for their worshippers. Emily Teeter, an Egyptologist and research assistant at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago told Archaeology magazine: "For years people have debated what kind of music it was. But there's no musical notation left, and we're not sure how they tuned the instruments or whether they sang or chanted." Some scholars have suggested it may have sounded like rap because there was a string emphasis on percussion, and with this presumably rhythm. Images often show people stamping their feet and clapping. Examples of song lyrics are recorded on temple walls. Some of the songs were sung at at the Festival of Opet in Thebes when the cult images of the gods Amun, Mut, and Khonsu were brought by boat down the Nile and carried in a procession to renew the pharoah's divine essence. One lyric from the festival goes: “Hail Amun-Re, the primeval one of the two lands, foremost one of Karnak, in your glorious appearance amidst your [river] fleet, in your beautiful Festival of Opet, may you be pleased with it.” [Source: Julian Smith, Archaeology, Volume 65 Number 4, July/August 2012]

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote in her article:“Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt”: “It is almost certain that Egyptian music, if not already heptatonic and modal, became so in the New Kingdom under Asian influence. This is confirmed by allusions in late Greek authors such as Dio Cassius and by the study of the Siwa songs. It does not preclude, however, the survival of very ancient pentatonic or hexatonic melodies. [Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010]

A popular ancient Egyptian song went:

” There is a welcoming inn.

Its awning facing south;

There is a welcoming inn” .

Its awning facing north;

Drink sailors of the Pharaoh.

Beloved of Amun.

Praised of the gods.” ♀

The Egyptians had puppets: little movable figures made of gold and carried in sacred processions. The first dramas according to some scholars were plays that told of the pharaoh’s birth at his enthronement. Plays about resurrection were often performed at the pharaoh’s funeral.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Music of the Most Ancient Nations - Particularly of the Assyrians, Egyptians and Hebrews” by Carl Engel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Musical Aspects of The Ancient Egyptian Vocalic Language” by Moustafa Gadalla (2016) Amazon.com;

““Music and Musicians in Ancient Egypt” by Lise Manniche (1992) Amazon.com;

“Love Poetry and Songs from the Ancient Egyptians” by Gilbert Moore (2015)

Amazon.com;

“Echoes of Egyptian Voices: An Anthology of Ancient Egyptian Poetry” translated by John Foster (1992) Amazon.com;

The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry” by William Kelley Simpson, Robert K. Ritner, et al. (2003) Amazon.com;

“Writings from Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkerson (2016) Amazon.com;

“Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple” by David Klotz | (2006) Amazon.com;

Hymns, Prayers and Songs: An Anthology of Ancient Egyptian Lyric Poetry”

by Susan Tower Hollis and John L Foster (1996) Amazon.com;

“Meditation Music of Ancient Egypt” by Gerald Jay Markoe (CD) Amazon.com;

“Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2010) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Dances” by Irena Lexová (1999) Amazon.com;

Evidence of Music in Ancient Egypt

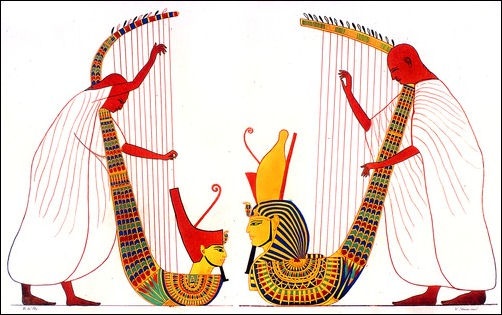

bow harp

Sibylle Emerit of the Institut français d'archéologie orientale wrote: “Iconographic, textual, and archaeological sources show that music played an essential role within ancient Egyptian civilization throughout all periods. Music was of utmost importance in rituals and festivals. Different forms of music with multiple functions existed for public or private representations, profane or sacred, interpreted by male or female musicians acting as professionals or amateurs. Consequently, from religious celebrations to entertainment, the range of types of music and musicians was very large. [Source:Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The sources concerning Egyptian music represent various types of iconographic, archaeological, and textual documents from different locations. They cover the entire Egyptian history, from the Predynastic to the Roman Periods, i.e., from 3100 B.C. to the fourth century CE. The principal information comes from representations on the walls of private tombs and temples. There are also numerous depictions of musical scenes on coffins, papyri, ostraca, and on objects like spoons, plates, and boxes, etc. In addition, many three-dimensional representations such as statues and statuettes, terracottas, and amulets of musicians are extant.

“Adding to the iconographic evidence are numerous, most often concise inscriptions in hieroglyphs, hieratic, Demotic, and Greek, which are found not only on papyri, stelae, statues, and musical instruments, but also as legends for the representations on the walls of tombs and temples. In the New Kingdom, the textual evidence is particularly rich: we have the so-called Harper’s Song, “love songs”, or certain “ritual texts,” which were supposed to be chanted and were often accompanied by one or several instruments. These sources allow the identification of the names of musical instruments, titles of musicians, and vocabulary of musical actions, which describe repertoires as well as techniques for playing. The translation of these terms remains, however, difficult since one lexeme can have several meanings and an object several names.

“Archaeology has also provided us with traces of various musical instruments, from the simple percussion object to the more complex cordophone. For most of these objects the provenance remains unknown since they entered the museums as early as thes econd half of the nineteenth century after having being purchased from the art market(Anderson 1976; Sachs 1921; Ziegler 1979).In spite of the richness of the documentation, our knowledge of Pharaonic music remains limited: without theoretical treaty, or musica lscore, it is indeed particularly difficult to do an archaeology of music.”

Musical Instruments in Ancient Egypt

Harpers

Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin wrote: “Almost all categories of instruments were represented in Mesopotamia and Egypt, from clappers and scrapers to rattles, sistra, flutes, clarinets, oboes, trumpets, harps, lyres, lutes, etc. ...In the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.), Egypt borrowed several instruments from Mesopotamia: the angular vertical harp, square drum, etc. The organ, invented in Ptolemaic Egypt, is first attested in its new, non-hydraulic form in the third century a.d. Hama mosaic.[Source: “Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt by Marcelle Duchesne Guillemin, World Archaeology, Volume 12, 1981 - Issue 3, Pages 287-297, published online: 15 July 2010 ^*^]

“Names of musical instruments are fairly well known owing to the hieroglyphic inscriptions accompanying the paintings, but they are rather vague : for instance the word mat designates the flute as well as the clarinet. No document has yielded any indication about the music, either theoretical or practical. Ancient music may have survived to some extent in that of the tribes of the Upper Nile or in oases such as that of Siwa. This might be suggested by some satirical songs dealing with animals, in the line of fables and scenes depicted on papyri and ostraca. They have been recorded by Hans Hickmann, a more positive contribution than the hypotheses he has put forward in numerous publications about the so-called chironomy and the play of musical instruments. Sachs’ early polyphonic theory, based on pictures of harpists, is without foundation, for it cannot be proved that both hands of the harpist struck any two strings simultaneously, while his further theory of the pentatonic basis of ancient oriental music has been disproved by the discovery of the heptatonic system in ancient Mesopotamia. ^*^

“The instruments may be classified following normal practice proceeding from the simplest to the most complex, into idiophones (clappers and the like), membranophones (drums), aerophones (flutes and reed instruments) and chordophones (string instruments). ^*^

See Separate Article: MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Musical Notation in Ancient Egypt

lute player

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “In the 1960s, Hans Hickmann claimed to have discovered a system of musical notation based on chironomy or gesticulations. Indeed, he saw in the variations of the positions of the hands and the arms of the singers depicted in music scenes in Old and Middle Kingdom private tombs a way to indicate to the musicians the musical intervals of fourth, of fifth, or octave. This idea met with a deep interest, but it is widely questioned today because this body language is not really codified suggested a system of musical notation indicated with dots and red crosses placed above a Demotic text dating from the first or the second century B.C., which was discovered in Tebtunis. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“These signs of an extreme simplicity could transcribe, according to her, a rhythmic punctuation intended to be played by a percussion instrument. She based this interpretation on the fact that this papyrus contains an Osirian liturgy and that drums could be used in this ritual context. However, this interpretation may be going too far, because research on text metrics shows that the literary and religious texts, intended to be recited, were composed in a rhythmic structure. Red dots aided the pupils in learning how to recite and to remember the scansion. According to the Deir el-Medina ostracon 2392, this recitation could be moreover accompanied by a musical instrument. The notation in P. Carlsberg 589 differs from the usual signs because apart from the dots also several crosses were inscribed over the text. Hoffmann interpreted these signs as an aid for the priest in charge of the declamation as to how to accentuate a group of words.

“It seems surprising that the Egyptian civilization, which developed an elaborate system of writing very early on, did not find a means to record music—but many cultures have lacked such a system. Musical notation is not indispensable for the transmission of musical knowledge. Its use matches a specific cultural need, such as, for example, the sharing of the musical pieces. In addition, the ancient Greek musical notation was invented at the end of the sixth century or at the beginning of the fifth century B.C., and several Greek musical papyri of Hellenistic and Roman time were discovered in Egypt. Apparently, the Egyptians did not adopt this technique for their own music.”

Musicians in Ancient Egypt

lute players

Every large household had its harem and the inmates were careful that music and song should never fail at any feast, secular or sacred. In the royal household moreover, where the musicians were very numerous. It is certainly not accidental that in the pictures of the Old Kingdom the women appear always to sing without, and the men with, instrumental accompaniment. Perhaps women's voices were considered pleasant to listen to alone, but the men's, on the other hand, were preferred with harps and flutes.

During the Old Kingdom instrumental music seems to have been performed mainly by men, and to have served as an accompaniment to the voices. The instruments commonly used at a concert of that time consisted of two harps, a large and a small flute; while close to each musician stood a singer, who also beat time by clapping his hands. On rare occasions the harp was employed alone to accompany singing, but at this earlier period flutes were never used alone. During the New Kingdom on the other hand women performers were more frequent, and female as well as male voices were combined with all manner of instruments. A large harp, two lutes (or a lute and a lyre) and a double flute were used at this later period as the usual accompaniment to the voices. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Women often sang as an accompaniment to the dances. It was the usual custom for singers to mark the time by clapping their hands; men waved their arms quickly when singing, while etiquette forbade the women to do more than move their hands, Even under the New Kingdom this custom of beating time was in use, more scope however was allowed in their manner of singing, and male and female voices were employed individually, or together with instruments. The blind, of whom there have always been many in Egypt, were much liked as singers; “the best school for female singers was at Memphis.

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “In Pharaonic society, both men and women could choose to devote themselves entirely to music. Among them were musicians of foreign origin, children, and dwarfs. From the beginning of the ancient Egyptian civilization, the musical art was also the privilege of some divinities. However, the iconography of musician gods developed especially in Greco- Roman temples. In this context, Hathor, Mistress of music, was depicted playing tambourine, sistrum, and menit-necklace, often in the form of the seven Hathors (goddesses of fate who are present at childbirth). Hathor’s son Ihy shakes the sistrum and menit for her. Meret, Mistress of the throat, was represented as a harp player. Bes and Beset were depicted dancing while playing trigon harp, lute, or tambourine. Priests and priestesses played the role of the gods in rituals. For example, in the Osirian liturgy, two young women were chosen to personify Isis and Nephthys and play tambourine for the god. Lastly, animals playing musical instruments are an iconographic theme known continuously from the Old Kingdom to the Roman Period(figs. 3 and 15). For instance, a monkey with adouble oboe, a crocodile with a lute, a lion with a lyre, and an ass with a harp are depicted in the Turin Erotic Papyrus. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

Organization of Musicians in Ancient Egypt

Musicians were under a superintendent, who may be regarded as a professional. A number of names of these ancient choir-masters have come down to us. Under the Old Kingdom we meet with a certain Ra'henem, the “superintendent of the singing," “who was also the superintendent of the harem. There were also three “superintendents of the royal singing “who were at the same time “superintendents of all the beautiful pleasures of the king" — their names were Snefrunofr, 'Et'e, and Re'mery-Ptah; the two last were singers themselves and boast that they “daily rejoice the heart of the king with beautiful songs, and fulfil every wish of the king by their beautiful singing. " At court they held a high position, they were “royal relatives," and priests of the monarch and of his ancestors. Under the New Kingdom we find H'at-'euy and Ta singers to Pharaoh, and Neferronpet the “superintendent of the singers to Pharaoh," who was at the same time “superintendent of the singers of all the gods," and therefore at the head of the musical profession in Egypt. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “The musicians’ titles reveal that their professions were more or less structured and organized into a hierarchy according to their musical specialty, the most complex body being the Hsw. Also, they indicate very often the name of the deity to which the musician plays and/or the place where he practices: usually in the palace or a temple. During their career, certain artists could attain high ranks, such as sHD (“inspector”), xrp (“director”), jmj-rA (“overseer”), jmj (“director”), and Hrj (“superior”). However, it is difficult to understand how these levels worked together and to which types of skills they referred. On the other hand, it is certain that these ranks were not purely honorary because their holders generally led a group of persons or oversaw the music in a precise area (palace, temple) or a whole region. Female musicians rarely reached this high level, but their hierarchical organization did not apparently follow the same pattern as that of the men, especially from the New Kingdom onwards when their number continually increased. Connected to the service of a temple, they were distributed within phyles as common priestesses. It is likely that they were subordinated to the wrt xnrt (the great one of the institution-kheneret) or to the Divine Adoratrices, but this link is not sufficiently explicit in the records. If most of the Hsyt, Smayt, and jHyt really were exercising their art, it seems certain that these titles also had a honorary character. Finally, from the New Kingdom onwards, there was a choir (šspt d-xnw) that brought together men as well as women. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“It is not unusual that a male musician or a female musician used several titles in connection with the music. For example, in the Old Kingdom, Temi was at the same time sbA and Hsw , whereas in the Third Intermediate Period, Henouttaoui was šmayt and wDnyt. Musicians’ titles also indicate that they often occupied other functions in Egyptian society. It was usually a position in the priestly hierarchy, but they could also attain offices in the royal administration. For example, in the Old Kingdom, Ptahaperef was “Inspector of the craftsmen of the palace” and Raur was “Overseer of linen”.”

Types of Musicians in Ancient Egypt

girl tuning a lute

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “One of the paradoxes of the ancient Egyptian documentation is that there is a discrepancy between the number of musical specialties expressed in the iconography and in the vocabulary. The iconographic sources allow the identification of at least 12 categories of artists: singers, harpists, players of lute, lyre, long flute, double clarinet, oboe, double oboe, trumpet, and tambourine, as well as percussionists and rhythmists. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The number of musicians’ titles is, on the other hand, more difficult to establish, because for some of them the translation is hypothetical (to the extent that it is even uncertain whether they are musicians), whereas the names of other professions remain unknown. Furthermore, if titles such as jHwy, “percussionist”, or Dd-m-šnb, “trumpet,” describe a single musical specialty, others such as Hsw, šmaw, and xnw/d-xnw indicate musicians who can play several instruments and, sometimes, who can also dance. Thus, the Hsw is above all a singer who can accompany himself by clapping in his hands or by playing a stringed instrument: harp, lute, or lyre. The lute can also be played by the dancer Tnf.

“The main function of a xnw/d-xnw is marking the cadence by clapping hands or with a percussion instrument; this rhythmist is also able to use his voice to punctuate its interventions, probably by the scansion. Finally, the šmaw strikes the cadence with his hands, sometimes by carrying out a dance step or by singing, using in exceptional cases a harp. The dividing line between music and dance is not always clear. An analysis of the terms related to the semantic field of music also reveals the importance of rhythm in the concept of this art in ancient Egypt. The titles Hsw, šmaw, xnw/d-xnw, or jHwy are used for men and women, but they do not cover exactly the same artistic activities and vary by gender. Other titles like Dd-m-šnb and sbA,“flutist,” are attested only for male musicians, whereas sxmyt, jwnty, and nbty are known only for female musicians.

“Through the contact with other antique cultures, new instruments were adopted in Egypt, giving birth to new musical specialties. For example, the introduction of the double oboe during the New Kingdom was followed by the creation of the title wDny, “double oboe player.” Some titles were increasingly fashionable, as Hsyt and šmayt, which developed especially from the New Kingdom onwards to become particularly popular in the Third Intermediate Period. Despite the evolution of musical tastes, it is necessary to underline the perpetuity of the harpist figure from the Old Kingdom to the Roman Period, whether in the iconography or through the title of Hsw, which remains the most common in the documentation.”

Music Training, Compositions and Performances in Ancient Egypt

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “Music was performed in several types of spaces, public and private: inside the temple, the palace, during religious processions, military parades, during burials to maintain the funerary cult, or also during private festivities. Access to these spaces reveals the status of the artists and the music. Musicians, such as singers, exercised their profession in practically all social spheres, whereas the musical practice of other artists was limited to a particular context or event, such as the military and royal context in which the trumpet was used. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Depending on the period, the orchestras’ composition evolved. In the Old Kingdom banquet scenes, the bands include singers, rhythmists, harpists, and long flute and double clarinet players. In the New Kingdom, new instruments appeared: tambourines, lutes, lyres, and double oboe enter henceforth the musical groups. Some artists played solo, such as harpists and lute players, whether it was to interpret the Harper’s Song or to play in front of a divinity. The trumpeter was the only musician to follow the sovereign to war, while in the royal escorts, drummer and rhythmists were also present. According to the context, music had different functions. For instance, in the temple ritual it was used to gladden the god and to pacify him, whereas in a funerary context it could help the rebirth of the dead. A few rural scenes also show singers and flutists entertaining the workers in the agricultural fields.

“The existence of a hierarchical organization of the musician’s profession raises the question of the training in their discipline. Although very rare, some documents allow us to assert that music schools existed and that some sort of institutional teaching was given within the court or the temples. In the Old Kingdom, several instructors are known with the title sbA, who taught music and dance. In the Middle Kingdom, Khesu the Elder is depicted in his tomb giving lessons to female musicians in sistrum playing and hand-clapping showed that part of the palace musicians belonged to the xntj-š group, which brought together royal attendants. Musicians were apparently recruited from among these people. The learning of music certainly began within the family. Indeed, by comparing titles, it is clear that it was not uncommon for numerous members of a lineage to all be musicians.”

Status of Musicians in Ancient Egypt

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “Several elements within the documentation allow us to understand the social and economic status of an individual and to recognize his uniqueness compared to other members of society. The status markers for musicians are of two kinds: archaeological remains and titulary. The nature of archaeological remains is related to the quantity of monuments and objects, which belonged to the musicians, or where the musicians are mentioned or represented. Indeed, a musician known by his inscribed tomb does not have the same economic and social status as the musician who could only erect a stela or statue in a sacred place. Nevertheless, most musicians did not possess a funeral chapel, but simply a monument or commemorative object with their name, such as a false-door, stela, rock inscription, statue, shabti, box with shabtis, libation basin, offering table, textile, or seal. Others are known only from the evidence in the tomb or on the stelae of a personality of high rank, their names being sometimes only enumerated in lists of temple employees, in letters, or official documents. The titulary of a musician reveals his social and economic status. It is composed of several elements including titles, epithets, and sentences of laudatory character, the names of the person, and affiliations. It therefore allows us to place the individual in an enlarged familial and social frame. It is not uncommon to see a musician involved in other functions in society that may have been a source of supplementary income or prestige. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ] “Sources show that the economic and social status of the musicians varied a lot according to individual and gender. From a quantitative point of view, the female musicians occupy a more important place in the iconographic and textual records. Some of them even belonged to the royal family. Since the Old Kingdom, the role of sacred musician, shaking sistra and menit-necklaces for the Hathor cult or other divinities, was devolved to queens and girls of royal blood. However their status and function cannot be compared to those of a musician who played music to earn his subsistence. Nevertheless, the male musicians’ social recognition seems superior to that of the female musicians because some male musicians possess their own tomb, which is a sign of royal favor. Thus, this privilege was not restricted to persons in charge of religious, administrative, political, or military tasks. The economic and social status of female musicians seems to rather be determined by that of their spouse, especially from the New Kingdom onwards. Often married to a high dignitary, they are represented or named with him on their monuments (be this tombs, stelae, or statues). Some objects, however, were dedicated by these women and used as memorial in places of pilgrimage, as Abydos. However, a prosopographical documentation is specific to the female musicians who lived during the 21th Dynasty: the sarcophagi from the Deir el- Bahari Cachette and the funerary papyri.

“Since the musician did not produce his subsistence, he was dependent on an employer, who was in charge of his living costs. Those who were attached to the palace or a temple were privileged and comparable to other “functionaries.” If a few musicians are known to us by a title or a name, we should be aware that a large part of the artists involved in the musical life in ancient Egypt definitely is not known to us. Most of them remained anonymous, because they could not afford to leave an epitaph, or their monuments did not survive the ages. That is what the “East Cemetery” of Deir el-Medina dating to the 18th Dynasty seems to testify. The study of the non-epigraphic material from these tombs, in which numerous musical instruments were discovered, reveals that the persons buried in this place belonged to a modest social class attached to the service of local noblemen. Among them were apparently musicians of both genders. It is probable that their function was not limited to music and that they also participated in domestic tasks.

“The Greek papyrological documentation of the Hellenistic and Roman Periods contains some examples of contracts for hiring musicians. It was possible to rent these artists to animate religious or private festivities. That is also shown in a Demotic papyrus of the first or second century CE in which the adversities of a poor talented harpist are related, who goes from place to place, begging for his meal in exchange of his art. This type of punctual hiring, which was certainly common previous to the Ptolemaic Period, reveals the precarious status of the itinerant musician compared to the one who was attached to the court or to the temple. We find an echo of this practice in the Papyrus Westcar where three goddesses, dressed as musicians/dancers-xnywt, offer their service to Redjedet to help her give birth.”

Clothing of Musicians in Ancient Egypt

Sibylle Emerit wrote: “Generally, musicians never wear ceremonial dress or distinguishing features connected to their profession, even when they perform their art. The only identifying feature is the particular instrument they hold. In P. Westcar, the husband of Redjedet identifies the goddesses as musicians/dancers-xnywt because they show him their sistrum and menit-necklaces. An unusual feature should be noted in Amarna: in the iconography,musicians are dressed with a hat of conical shape, a flounced skirt, and a short cape, but these clothes are probably linked to their foreign origin and are not stage clothes. [Source: Sibylle Emerit, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Certain musical specialties seem to be reserved for a particular ethnic group, as, for example, the barrel-shaped drum, which is usually struck by Nubians. This is not, however, a generality, because this instrument is also played by Egyptians. The Nubians are perfectly recognizable in the iconography whether it is by their facial features or the loincloths they wear.

An Egyptian Feast by Edwin Longsden

“Physical characteristics differentiate the Egyptian musician from the others in the iconography. In the Middle and New Kingdom, the harpists are often represented obese and old, whereas their eyes are generally closed. It has long been considered that these artists were blind; however, this characteristic is certainly more symbolic than real. In the 19th Dynasty funerary chapel of Reia, this is clearly an iconographic topos: when this overseer of the Hsw-singers is depicted playing the harp, he is blind, while in the other scenes of his tomb he is not and is depicted as an ordinary noble.”

Work and Drinking Songs in Ancient Egypt

One of the greatest pleasures of the fellahin in the 19th century, when working the shadoofs or water-wheels, was to drone their monotonous song; their ancestors also probably accompanied their work with the same unending sing-song. A happy chance has preserved two such songs for us. One, of the time of the 5th dynasty, was sung by the shepherd to his sheep when, according to Egyptian custom, he was driving them after the sower over the wet fields, so that they might tread in the seed into the mud. It runs somewhat as follows: “Your shepherd is in the water with the fish, He talks with the sheath-fish, he salutes the pike From the West I your shepherd is a shepherd from the West.” [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The meaning is that the shepherd is making fun of himself for having thus to wade through the puddles, where the fish call out good-day to him. Of the time of the 18th dynasty, however, we have the following little song, sung to the oxen by their driver, as he drove them ever round and round the threshing-floor:

Work for yourselves, work for yourselves. Ye oxen.

May you work for yourselves, The second grain for yourselves I The grain for your masters I "

There is also an ancient Egyptian drinking song which seems also to have been known to the Greeks. The latter relate that at a feast the figure of a mummy was carried round with the wine, in order to remind the guests of death, while in the enjoyment of this fleeting life; the subject-matter of our song agrees as nearly as possible with this custom. The oldest version that has come down to us is the “Song of the house of the blessed King 'Entuf, that is written before the harper "; “it was a song therefore that was written in the tomb of this old Theban monarch near the representation of a singer. It has also come down to us in two versions of the time of the New Kingdom, and must therefore have been a great favorite:

“It is indeed well with this good prince I The good destiny is fulfilled. The bodies pass away and others remain behind, Since the time of the ancestors. The gods (i. e. the kings) who have been beforetime, Rest in their pyramids, The noble also and the wise Are entombed in their pyramids. There have they built houses, whose place is no more. Thou seest what has become of them. I heard the words of Ymhotep and Hardadaf, Who both speak thus in their sayings: ' Behold the dwellings of those men, their walls fall down. Their place is no more. They are as though they had never existed. '

Opet Festival Songs

Tutankhamen scenes in the Temple of Luxor record the texts of three songs , chanted by priests and priestesses, accompanying the procession of cult images during the Opet Festival in Thebes. The First Song goes:

“Oh Amun, Lord of the Thrones of the Two[Lan]ds, may you live forever!

A drinking place is hewn out, the sky is folded back to the south;

a drinking place is hewn out, the sky is folded back to the north;

that the sailors of Tutankhamen (usurped by Horemheb), beloved of Amun-Ra-Kamutef,

praised of the gods, may drink.” [Source: John Darnell, Yale, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

John Darnell of Yale University wrote: “The directions, south and north, may allude to the southeast to northwest flight of the sun . The implied south to north journey of this song—like the actual return to Karnak from Luxor at the end of the Opet Festival—relates to the royal New Year’s Festival and the return of the wandering solar goddess from the south. The drinking place would be one of the booths that celebrants erected during nautical festivals. Such booths are consistent with the aspect of sexual union inherent in the Opet Festival; Neith probably appears in her role as “Lady of inebriation in the (season of) the fresh inundation waters”. The journey by land and a return by river—as the Opet Festival appears under Hatshepsut and Thutmose III—would thus evoke the dry period prior to the union of the god and returning solar goddess, the return to the north by river likewise emphasizing the returning flood. The journey to the south by land, and the towing of the barks against the current in the southerly riverine journey, also mirrored the nocturnal journey of the sun in the dry realms of the Land of Sokar. The sails of the barks appear to have been red in color, the return journey to Karnak thus evoking the red light of dawn, the veil of the new born solar deity.

“Second Song: Recitation:

“Hail, Amun, primeval one of the Two Lands, foremost one of Karnak,

in your glorious appearance amidst your [riverine] fleet,

on your beautiful Festival of Opet— May you be pleased with it.”

Third Song:: Recitation four times—Recitation for the bark:

“A drinking place is built for the party, which is in the voyage of the fleet.

The ways of the Akeru are bound up for you; Hapi is high.

May you pacify the Two Ladies, oh Lord of the White Crown/Red Crown.

It is Horus, strong of arm, who conveys the god with she the good one of the god.

For the king has Hathor already done the best of good things.”

The ways of Aker allude to the east/west axis of the solar journey, parallel to the first song’s “royal” south/north axis The songs associate the festival journey to the course of the sun , and at the same time allude to sexuality. The “best of good things” finds echoes in New Kingdom love poetry, a term for the consummation of sexual union. A further detail confirming the sexual aspect of the festival is a statement of a priest who bends forward and addresses the bark of Amun as it emerges from Luxor Temple at the end of the Opet Festival: “How weary is the cackling goose!”. This short statement alludes to the cry of creation uttered by the great cackler in the eastern horizon, appropriate to the smn-goose form of Amun as the deity prepares to sail to Karnak.”

female musicians

Music and Entertainment at an Ancient Egyptian Feast

During the performance of music and dancing at feasts, the guests in no way appear so engrossed in these pleasures as is required by etiquette at our musical soirees. On the contrary, they drink and talk, and busy themselves with their toilette. As I remarked above, the Egyptian idea of a social feast was that the guests should be anointed and wreathed by the attendants, that they should receive new necklets, and that lotus flowers and buds should be placed on the black tresses of their wigs. If we look at the feast represented in the accompanying plate/ or at any one of the many similar pictures “of the New Kingdom, we see how absorbed the women of the party are in their own adornment; they give each other their flowers to smell, or in their curiosity they take hold of their neighbour's new earrings. The serving boys and girls go round offering ointment, wreaths, perfumes, and bowls of wine. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Singers challenge the guests at the same time to “celebrate the joyful day” by the enjoyment of the pleasure of the present moment; the singers also continually repeat the same as the refrain to their song. They sing to the guests as they quaff the wine:

“Celebrate the joyful day! Let sweet odours and oils be placed for thy nostrils, Wreaths of lotus flowers for the limbs And for the bosom of thy sister, dwelling in thy heart Sitting beside thee.”

“Let song and music be made before thee. Cast behind thee all cares and mind thee of pleasure. Till Cometh the day when we draw towards the land That loveth silence." or:

“Celebrate the joyful day, with contented heart And a spirit full of gladness." or:

“Put myrrh on thy head, array thyself in fine linen Anointing thyself with the true wonders of God. Adorn thyself with all the beauty thou canst.

“With a beaming face celebrate the joyful day and rest not therein. For no one can take away his goods with him. Yea, no one returns again, who has gone hence."

The guests, hearing these admonitions to enjoy life while thcy may, before death comes to make an end of all pleasure, console themselves with wine, and finally, as was considered suitable at every feast, “the banquet is disordered by drunkenness. Even the ladies do not refrain from excess, for when they at last refuse the ever-offered bowl, they have already, as our picture shows, presumed too much on their powers. One lady squats miserably on the ground, her robe slips down from her shoulder, the old attendant is summoned hastily, but alas I she comes too late. ' This conclusion to the banquet is no exaggerated caricature. In other countries and in other ages it may also happen that a lady may drink more than she need, but in the Egypt of the New Kingdom, where this pitiful scene is perpetuated on the wall of a tomb, it was evidently regarded as a trifling incident, occurring at each banquet, and at which no one could take offence. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Tomb of the Singing Enchantress

In 2011, a team from Switzerland's Basel University headed by Elena Pauline-Grothe and Susanne Bickel discovered the tomb of a female singer dating back almost 3,000 years in Egypt's Valley of the Kings. The woman, Nehmes Bastet, was a singer for the supreme deity Amon Ra during the Twenty-Second Dynasty (945-712 B.C.), according to an inscription on a wooden plaque found in the tomb. She was the daughter of the High Priest of Amon. The discovery is important because "it shows that the Valley of the Kings was also used for the burial of ordinary individuals and priests of the Twenty-Second Dynasty. Until then the only tombs found in the historic valley were those linked to ancient Egyptian royal families. The singer’s presence there would appear to indicate that she was of very high status. [Source: AFP, January 16, 2012]

The four-by-two-and-half-meter burial chamber provides a rare glimpse into the life of an ancient Egyptian singer. Julian Smith wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The black coffin carved from sycamore wood and decorated with large yellow hieroglyphs on its sides and top. The hieroglyphs describe the tomb's occupant, named Nehemes-Bastet, as a "lady" of the upper class and "chantress [shemayet] of Amun," whose father was a priest in the temple complex of Karnak in Thebes. The coffin's color and hieroglyphs match a style that dates to between 945 and 715 B.C., at least 350 years after the tomb was built. The coffin shows that the burial chamber had been reused, a common practice at the time. “The only other artifact dating to the same period as the coffin was a wooden stele, slightly smaller than an iPad, painted with a prayer to provide for her in the afterlife, and an image that is believed to be of Nehemes-Bastet in front of the seated sun god Amun. The white, green, yellow, and red paints hadn't faded a bit. Bickel says.[Source: Julian Smith, Archaeology, Volume 65 Number 4, July/August 2012 ==]

“Nehemes-Bastet lived during the Third Intermediate Period, a time when Egypt was split by intermittent wars between the pharaohs in Tanis and the high priests of Amun in Thebes, who rivaled the traditional rulers in wealth and power. "It must have been a pretty unsettling period," says Emily Teeter, an Egyptologist and research assistant at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. "There was fighting among these factions around her time." ==

“Nehemes-Bastet was one of many priestess-musicians who performed inside the sanctuaries and in the courts of the temples. "The hypothesis is that these women would sing, act, and take part in festivities and big ritual processions that were held several times a year," Bickel says. The musical instruments that chantresses typically used were the menat, a multi-strand beaded necklace they would shake, and the sistrum, a handheld rattle whose sound was said to evoke wind rustling through papyrus reeds. Other musicians would have played drums, harps, and lutes during religious processions. ==

"It's interesting that in this period even a wealthy girl was buried with quite simple things," Bickel says, comparing Nehemes-Bastet's coffin and stele with the elaborate pottery, furniture, and food found in earlier tombs. "Her wooden coffin was certainly quite expensive," she says, but nonetheless, it lacked the elaborate inner coffins found in similar burials. More details on Nehemes-Bastet's daily life can be drawn from a wealth of paintings, texts, and reliefs carved on statues and stelae of the time, says Teeter. As a chantress, or singer, in the temple of Amun, she probably lived in the 250-acre Karnak temple complex located in Thebes. Her name, translated as "may Bastet save her," indicates that she was under the protection of the feline goddess and "divine mother" Bastet, the protector of Lower Egypt. Nehemes-Bastet's occupation, however, was to worship Amun, the king of ancient Egyptian gods.” ==

The title "Chantress of Amun" belonged to women of the upper classes, Teeter says. Genealogies show multiple generations of women held the title, with mothers probably teaching the profession to their daughters. "It was a very honorable profession," says Teeter. "These women were well respected in society, which is why [Nehemes-Bastet] was buried in the Valley of the Kings." As was the case with the priests, temple singers were paid from the income generated by the huge tracts of land that Amun "owned" across Egypt. Some priests and priestesses served in the temples only a few months out of the year before returning home. There's little information about what women like Nehemes-Bastet would have done while at home, Teeter says, but it probably wasn't too different from other women's traditional duties of the time: running the household, raising children, and supporting their husbands.” ==

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024