PAINTING IN ANCIENT EGYPT

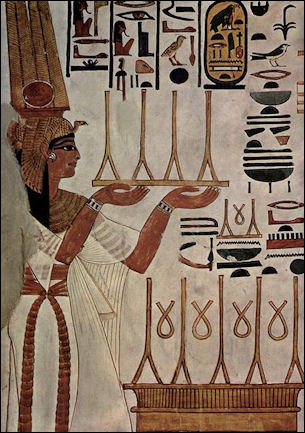

Nefertari tomb paintingThe Egyptians painted on papyrus rolls, tomb walls, coffin lids and a host of other surfaces. Egyptians used a variety of materials for pigments. They made yellow and orange pigments from soil and produced blue and red from imported indigo and madder and combined them to make flesh color. By 1000 B.C. they developed paints and varnishes using the gum of the acacia tree (gum arabic) as their base.

Described Egyptian painting French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero (1846-1916) wrote: "Their conventional system differed materially from our own. Man or beast, the subject was never anything but a profile relived against a flat background. Their object, therefore, was to select forms which presented a characteristic outline capable of being reproduced in pure line upon a plane surface.”

“The calm strength of the lion in repose, the stealthy and sleepy tread of the leopard, the grimace of the ape, the slender grace of the gazelle and the antelope, have never been better expressed than in Egypt. But it was not easy to project man — the whole man — upon a plane surface without some departure from nature. A man cannot be satisfactorily produced by means of mere lines, and a profile outline necessarily excludes too much of his person."

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture”

by Richard H. Wilkinson (1994) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Painting and Relief” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Wall Paintings” by Francesco Tiradritti and Sandro Vannini (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” Multilingual Edition by Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Egypt: Revised Edition” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen, Norbert Wolf (2018) Amazon.com;

“Principles of Egyptian Art” by H. Schafer and John Baines (1986) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of Egyptian Art” by Émile Prisse d'Avennes (1991) Amazon.com;

“Highlights of the Egyptian Museum” by Zahi Hawass (2011) Amazon.com;

“Hidden Treasures of Ancient Egypt: Unearthing the Masterpieces of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo” by Zahi Hawass (National Geographic, 2004) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

“Eternal Egypt: Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum”

by Edna R. Russmann (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt At The Louvre” by Guillemette & Marie-Helene Rutschowscaya & Christiane Ziegler (trans Lisa Davidson). Andreu (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Egypt and the Ancient Near East”

by New York The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Peter F Dorman, et al. (1988) Amazon.com;

Perspective and Unnatural Poses in Ancient Egyptian Art

The Egyptians never developed perspective. Human heads often looked like the heads of flounders and soles — profiles with two frontal eyes placed on them. The human body was also twisted in an awkward position in which the shoulder faced the viewer but the waist and legs faced sideways. Quantity — such as number of prisoners killed in a battle or animals killed on a hunting trip — was expressed with the items painted in long rows. Ordinary people and servants were generally depicted as considerably smaller than gods, pharaohs, and other important people.

Different points of view often appeared in the same picture. An image of fisherman might include a side view of the fishermen and a top view of the fish swimming in a pond. It was considered important to show all the important features of a person which some say is why individuals are drawn with combined front and side views. The head is usually a side profile with the eyes drawn as they appear from the front. The shoulders and skirts are also presented from a front view.

Reliefs and paintings were often shown in profile with the eyes, eyebrows, shoulder and upper torso present on one head. While unnatural, these perspectives have become conventions of Egyptian art. Dorthea Arnold, curator of Egyptian art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, told Smithsonian, "These artistic conventions set the way to show people: axial, not symmetrical, afrontal confrontation, a set number of poses. It was almost like a language. Yet it was elastic, capable of any number of variations within the formula. It showed how creative the artist could be within the canon."

See Separate Article: PERSPECTIVE, POSES, FLATNESS AND DIMENSIONS IN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN PAINTING africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Painting and Expression

Even though Egyptian artists had difficulty with perspective and certain aspects of the human form, they were able to express subtle expression and individuality. They were also very good and recording nature. They produced images of birds and animals that allow modern scientists to identify the species.

The pharaohs were central to Egyptian painting as they were to other art forms. In most cases only the pharaoh, his wife and the people who were conquered by him, or who worked for him were the only people portrayed in Egyptian art. There were set symbols. For example, figures spread out their arms flat like a diver doing a swan dive when they were grieving. A bull's tail hanging down the back of a pharaoh’s skirt symbolized victory.

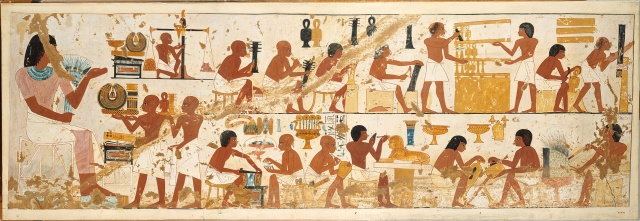

Ancient Egyptian tomb painting from 2500 B.C. graphically illustrated every day along the Nile. People are shown hunting, fishing, herding cattle, building boats, cultivating and irrigating their fields, harvesting crops, playing music, dancing, and making beer. Scribes were usually shown in a seated position like priests with a papyrus scroll and writing materials. Tombs of noblemen contained paintings with inventories of their possessions, to be taken with them to the afterlife.

New Kingdom Painting

Though the art of the New Kingdom was occupied chiefly with the decoration of large expanses of wall surface, yet it followed in a great measure the old paths. One innovation indeed we find — the artist was now allowed to represent a figure with that arm in advance which was nearest to the spectator. This was directly contrary to the ancient law of official art. But in other respects art rather retrograded than advanced, for the effort to keep to the old conventional style and to forbear following the ever-growing impulse in a more naturalistic direction, induced artists to lay more stress than was really needful on the stiffness and unnaturalness of the ancient style. We may remark, for instance, in the temple pictures of the New Kingdom, how, in the drawing of the hands, the points of the fingers are bent back coquettishly, and how the gods and the kings are made to balance whatever they present to each other on the edge of their hands. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

It was quite otherwise with art which was not officially recognised; the development of the latter we can admire in many pictures in the Theban tombs. In them we meet with fresh bright figures boldly drawn, though, as under the Old and the Middle Kingdom, amongst the servants and slaves. Asiatic captives may be represented according to the will of the artist, but their Egyptian overseer must stand there in stiff formality. The half-nude maiden who is serving the guests may be represented with her back to the spectator, with realistic hair, with arms drawn in perspective, and legs which set at nought every conventional rule, but the lady to whom she presents the wine must be drawn like a puppet of ancient form, for she belongs to the upper class.

In the picture of a feast we admire the freedom with which the singers and the dancing girls are drawn; the artist was evidently allowed a free hand with these equivocal characters; in fact the superstition of “good manners “did not here constrain him to do violence to his art. Fortunately official art was unable always entirely to withstand the influence of this freer tendency, and in pictures which otherwise follow the old rules we find little concessions to the newer style. This impulse was not only strictly forbidden, but repressed and stifled in the same way as the religious movement which stirred the people at the time of the 18th dynasty.

Once indeed an attempt was made to push forward this freedom in art and to replace the strict monumental style of old times by one more realistic. It is doubtless not accidental that this attempt at reforming art should coincide with the religious reform; the same king who, by inculcating his new doctrine, tried to remove the unnatural oppression which burdened the religion of the country, attempted also to relieve the not less unnatural tension under which art languished. A right conception lay at the root of both attempts, but neither had any permanent result. The violence of the proceedings of the monarch doubtless was the greatest impediment to them; on the one hand he desired entirely to exterminate the old gods, on the other hand he would have done away with all the dignity and restfulness of the old art, and allowed it even to verge upon caricature.

Reliefs in Ancient Egypt — Closer to Painting or Sculpture?

In Egypt we cannot, as we usually do now, reckon the art of relief as sculpture; it belongs from its nature to the art of painting or rather to that of drawing purely. Egyptian relief, as well as Egyptian painting, consists essentially of mere outline sketching, and it is usual to designate the development of this art in its various stages as painting, relief en creux (hollow relief) , and bas-relief If the sketch is only outlined with color, we now call it a painting, if it is sunk below the field, a relief en creux, if the field between the individual figures is scraped away, we consider it a bas-relief. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The style of drawing however is in all these cases exactly the same, and there is not the smallest difference in the way in which the figures are colored in each. At one time the Egyptian artist went so far as to seek the aid of the chisel to indicate, by modelling in very flat relief, the more important details of the figure; yet this modelling was always considered a sccondar) matter, and was never developed into a special style of relief.

Moreover the Egyptians themselves evidently saw no essential difference between painting, relief en creux, and bas-relief; the work was done most rapidly by the first method, the second yielded work of special durability, the third was considered a very expensive manner of execution. We can plainly see in many monuments how this or that technique was chosen with regard purely to the question of cost. Thus, in the Theban tombs, the figures which would strike the visitor first on entering are often executed in bas-relief, those on the other walls of the first chamber are often worked in relief en creux, while in the rooms behind they are painted.

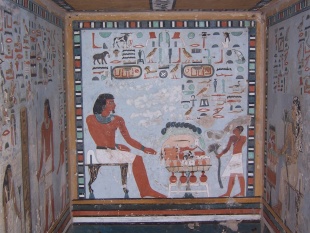

Ancient Egyptian Tomb Paintings

Tombs of kings, queens and nobles were typically decorated with murals with images of deities and people known to the deceased. Sometimes there were images of the daily lives of ordinary people. Images in tombs are often accompanied by texts from the “Book of the Dead” , which sometimes explain what is going on in the picture. Some of the greatest existing works of Egyptian art are the tomb paintings in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, particularly the tomb of Neferteri.

We are thankful to ancient Egyptian tombs and the ancient Egyptian belief that the afterlife was similar to life on earth and the deceased needed to bring things from their earthly life, including workers to perform chores, with them to the land of the dead. Artwork and grave goods that were entombed with the dead for these purposes has give us insights in the life of the ancient Egyptian and supplied us with wonderful works of art.

Heirakonpolis contains one of the oldest tomb painting. Created in 3200 B.C., it features stick-like figures. Some of the tombs have been dated to 5000 B.C..

The royal tombs were supposed to be decorated entirely in relief en creux, but it is seldom that this system of work is found throughout, for if the Pharaoh died before the tomb was finished, his successor generally filled up the remaining spaces cheaply and quickly with painting. When the details of a figure are worked out by the modeller, this is evidently considered a great extravagance, and is often restricted to the chief figure in a representation. Thus, for instance, in the tomb of Seti I., the face of this king alone is modelled, while his body and all the other numerous figures are given in mere outline. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TOMB PAINTINGS africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Palace Painting So Realistic the Bird Species In It Can Be Identified

An ancient Egyptian "masterpiece" painting of birds in a marsh is so detailed, scientists can tell exactly which species were painted more than 3,300 years ago. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The painting was discovered about a century ago on the walls of the palace at Amarna, an ancient Egyptian capital located about 186 miles (300 kilometers) south of Cairo. Although previous research has examined the mural's wildlife, the new study is the first to take a deep dive into the identity of all of the birds, some of which have unnatural markings. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, December 15, 2022]

Many of the birds depicted are rock pigeons (Columba livia), but there are also images showing a pied kingfisher (Ceryle rudis), a red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio) and a white wagtail (Motacilla alba), study co-researcher Christopher Stimpson, an honorary associate at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and study co-author Barry Kemp, professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Cambridge, wrote in a study published December 15 in the journal Antiquity. The team studied a facsimile (a copy) of the artwork and used previously published ornithological and taxonomic research papers to identify the birds.

The room, which today is known as the "Green Room," is painted with images of water lilies, papyrus plants and birds — a scene that may have created a serene atmosphere where the royal family could relax, the researchers said. It is "realistic to suggest that the calming effects of the natural environment were as important to the royal household then as it has increasingly been shown to be today," Stimpson and Kemp wrote in the study. It's possible that real plants were kept in their room along with perfume and that ancient Egyptians played music there. "A room adorned with, by any measure, a masterpiece of naturalistic art, and filled with music and perfumed by cut plants, would have made for a remarkable sensory experience," the researchers wrote.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Ancient Egyptian 'masterpiece' is so realistic, researchers identified the exact bird species it depicts” from Live Science livescience.com

Beautiful 2,200-Year-Old Painting Found Under Bird Poop at an Ancient Egyptian Temple

In 2022, researchers announced that they had uncovered a beautiful paintings of ancient Egyptian goddesses under layers of bird droppings at a temple in southern Egypt. In some of the images the goddesses were depicted as vultures. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, May 24, 2022]

Live Science reported: Archaeologists discovered 46 stunning depictions of goddesses in detailed and colorful frescoes created on the ceiling of a temple nearly 2,200 years ago. The temple is located at Esna, a city in southern Egypt that is about 60 kilometers (37 miles) south of Luxor (ancient Thebes). It is dedicated to Khnum, an ancient Egyptian god associated with fertility and water. Hieroglyphs on the temple show that it was used for nearly 400 years — between the time of pharaoh Ptolemy VI (reign 180 B.C. to 145 B.C.) and the Roman emperor Decius (reign A. D. 249 to 251), Christian Leitz, a professor and director of the Department of Egyptology at the University of Tübingen in Germany, told Live Science. Leitz is a member of the Egyptian-German team that is conserving and documenting the temple.

In October 2023, archaeologists announced that they had uncovered a New Year's scene from the Temple of Esna. Live Science reported: The paintings show the Egyptian deities Orion (also called Sah), Sothis and Anukis on neighboring boats with the sky goddess Nut swallowing the evening sky above them — a mythology that details the Egyptian New Year, according to a statement from the University of Tübingen in Germany, which jointly led the restoration with the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 19, 2023]

In the depiction, Orion represents the constellation of the same name, while Sothis represents Sirius, a star which was invisible in the night sky in ancient Egypt for 70 days of the year before becoming visible again in east, that day marking the ancient Egyptian New Year, Christian Leitz, an Egyptology professor at the University of Tübingen who is part of the team, said in the statement. The Nile seasonally flooded at this time, and the ancient Egyptians believed that about 100 days after the appearance of Sirius, the goddess Anukis was responsible for the receding of the Nile's flood waters. As the team finished cleaning the ceiling, they restored several other paintings. One of them — a representation of a lion's body with four wings and a ram's head — represents the "south wind," according to an inscription. In ancient Egypt, the south wind was associated with scorching heat and it's possible that the "lion represents the power of the heat," Leitz said.

See “Archaeologists had to remove two millennia of grime to reveal this ancient Egyptian artwork” in National Geographic N0 nationalgeographic.com

Painted Funerary Portraits from Roman-Era Egypt

Some of the greatest Roman-era paintings and works of art from Egypt were produced by Romanized Egyptians, who embalmed their dead, wrapped them as mummies, and painted portraits of the deceased on small wooden panels attached at the head of the shroud wrapped around the mummy wrappings. Sometimes these mummies were put on display before they were buried.

Barbara E. Borg of the University of Exeter in the UK wrote: “The term “painted funerary portraits” used here encompasses a group of portraits painted on either wooden panels or on linen shrouds that were used to decorate portrait mummies from Roman Egypt (conventionally called “mummy portraits”). They have been found in cemeteries in almost all parts of Egypt, from the coastal city of Marina el-Alamein to Aswan in Upper Egypt, and originate from the early first century AD to the mid third century with the possible exception of a small number of later shrouds. Their patrons were a wealthy local elite influenced by Hellenistic and Roman culture but deeply rooted in Egyptian religious belief. To date, over 1000 portraits, but only a few complete mummies, are known and are dispersed among museums and collections on every continent.” [Source: Barbara E. Borg, University of Exeter, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Fayum portrait

There is little archaeological evidence on the contexts in which the mummy portraits were found. Based on ones in which contetxs were reported: The variety of tomb types is remarkable—from simple sand pits to re-used older graves to magnificent new tombs built for an aspiring family—but one common feature seems to be the very simple form of deposition of the portrait mummies in entirely inconspicuous cavities or chambers and with only occasional, insignificant grave goods. This suggests that the costly and lavishly decorated mummies were mainly appreciated during the funerary ceremonies and festivals for the dead before burial.

Er-Rubayat in the oasis Faiyum some 50 kilometers south of Cairo is the place associated most with these portraits. However, as we know from sporadic additional information from other sites, the shallow sand pits in which he found the majority of the mummies were not the norm everywhere. At some places, e.g., at Saqqara, at er-Rubayat, or at Aswan, portrait mummies were buried in re-used rock-cut tombs from the Pharaonic Period. At Antinoopolis, the city founded by emperor Hadrian and named after his beloved Antinoos, and at Panopolis/Achmim, another site yielding a considerable number of portrait mummies, both tomb types were used.

See Separate Article: ROMAN-ERA EGYPTIAN MUMMY PORTRAITS africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024