ETHNICITY IN ANCIENT EGYPT

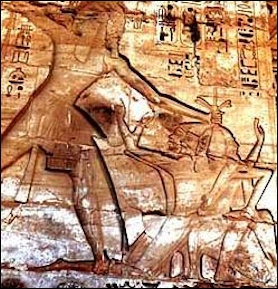

Sphinx of Taharqa, the Nubian pharaoh of Egypt

Robert Draper wrote in a National Geographic article about the black pharaohs of Nubia, “The ancient world was devoid of racism...Artwork from ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome show clear awareness of racial features and skin tone, but there is little evidence that darker skin was seen as a sign of inferiority, Only after the European powers colonized Africa in the 19th century did Western scholars pay attention to the color of Nubians’ skin." Some pharaohs had court dwarves and pet pygmies. Pygmies were often brought from sub-Saharan Africa to serve as temple dancers and acrobats in the service of Re, the Sun God.

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia and John Baines of Oxford University wrote: “As developed in the fields of anthropology and sociology, the concept of ethnicity offers one possible approach to analyzing diversity in the population of ancient Egypt. However, it is important that ethnicity not be elided with foreign-ness, as has often been the case in Egyptological literature. Ethnicity is a social construct based on self-image, and thus may be difficult to identify in the ancient sources, where a monolithic uniformity of “Egyptian” versus “other” prevails. A range of sources does suggest that ethnic difference operated within the indigenous population throughout Egyptian history, as would be expected in any complex society. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK; John Baines, Oxford University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Egyptological literature has tended not to distinguish between ethnicity and partly overlapping notions such as “foreignness,” focusing on the representation of generic foreigners in pictorial iconography, or on the movement of people through trade, migration, or conflict. Scholars have often adopted the Egyptians’ own ideological stance, by accepting and perpetuating the vision of a monolithic, definable Egyptian state and culture subject to “incursions” and threatened by other “races.” Some writers have seen a “dichotomy”between Egyptian concepts of inferior foreigners and the extensive evidence for political alliances, economic trade, immigration, and intermarriage with these same groups. Even writers engaged with anthropological and archaeological thinking about ethnicity limit discussion to the three broad groups of non-Egyptians (Nubians, Libyans, and Syro-Palestinians) commonly used as stereotypes in Egyptian art. The official record in Egypt does present ethnicity in this way, for purposes of rhetoric: foreign (as distinct from ethnic) groups are topoi for disorder, chaos, and otherness, while Egypt, as defined by its own elite, represents order, harmony, and the privileged vantage point. The ready availability of these topoi in Egyptian culture implies that the quality of being foreign was familiar and definable in Egyptian society. It may be reasonable to also extend this implication to ethnic groups within Egypt, even if they are less easily recognized in the ancient record, but one must also ask how far topos and reality coincided.

“The existence within Egypt of ethnic groups that were defined by social interaction, negotiation, and self-presentation has been little studied. The assumption that ethnic groups moved into Egypt from outside does not allow for ethnic differentiation within the indigenous or long-resident population of the Nile Valley and Delta or address the fate of immigrants and their descendants in Egyptian society. This question of their longer-term status has hardly been addressed in the modern literature. Moreover, regional or local identities may constitute a phenomenon comparable to ethnic identity, rather than cultural difference. The source material leaves both possibilities open, and draws attention to the range of elements that individuals and communities could bring to bear in defining ethnicity in opposition to a dominant cultural group. Many religious practices were strongly local, with emphasis placed on the cult of a specific town or nome in local hierarchies and on the use of personal names. Different dialects only become clear in Coptic, in which vowels are written, but such linguistic.”

“The dominant presentation of Egyptian monuments, which emphasizes uniformity among Egyptians and contrasts it with generally stereotyped diversity among foreigners, renders the identification of difference within ancient Egyptian society hard to identify. The concept of ethnicity offers one possible approach to analyzing differentiation, among ancient as well as modern populations, and a valuable corrective to the depicted uniformity, which, as scattered sources show, belies ancient realities. The essential limitation of the ancient material is its weak attestation of self-image vis-à-vis images of others or of “the other.” The sources therefore offer many ways of thinking about ethnically Egyptian dominance but few for thinking about how people related themselves to less general entities than the society as a whole, and still fewer for approaching diversity in the non-elite population. Comparative study shows that large-scale societies are rarely homogeneous in terms of ethnic self-definition, and we see no reason to suppose that Egypt was exceptional in this respect. Moreover, acculturation, as observed through the monumental and archaeological record, provides little guide to self-definition or to ascription of identity by others, which are the two essential aspects of social configuration addressed by the notion of ethnicity. People who are entirely acculturated, or who present minimal identifiers of difference, may possess a strong ethnic adherence. Given these difficulties, no full comprehension of such distinctions of identity in the ancient society can be achieved. Nevertheless, the indicators cited in this article suggest that any notion that the ancient Egyptian population was ethnically uniform in any period should be abandoned as a fiction projected by the dominant ideology and often largely accepted by Egyptologists.”

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

See Canaanites, History of Palestine, Libyans

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Foreigners in Ancient Egypt: Theban Tomb Paintings from the Early Eighteenth Dynasty” by Flora Brooke Anthony (2016) Amazon.com;

”The Role of Foreigners in Ancient Egypt: A Study of Non-Stereotypical Artistic Representations” by Charlotte Booth (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Iconography of Humiliation in New Kingdom Egypt: The Depiction and Treatment of Bound Foreigners” by Mark D. Janzen (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Society” by Danielle Candelora, Nadia Ben-Marzouk, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian State: The Origins of Egyptian Culture (c. 8000–2000 BC)” by Robert J. Wenke (2009) Amazon.com;

“Syro-Palestinian Deities in New Kingdom Egypt: The Hermeneutics of Their Existence” by Keiko Tazawa (2009) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Foreign And Animal Gods” by Lewis Spence (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Burden of Egypt” by John A. Wilson (1951) Amazon.com;

“Egypt: People, Gods, Pharaohs” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen (2009) Amazon.com;

“Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times” by Donald Redford Amazon.com ;

“Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, and Early Israel, 1300-1100 B.C.E.” by Ann E Killebrew Amazon.com;

“When Egypt Ruled the East” by George Steindorff and Keith C. Seele (1963) Amazon.com;

“Canaan and Canaanite in Ancient Egypt” by Alessandra Nibbi (1989) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile” by Marjorie M. Fisher, Peter Lacovara , et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Nubia — Fully Explained: A New History of the Nile Valley” by Adam Muksawa 2023) Amazon.com;

“The Mystery of the Land of Punt Unravelled” (2015) by Ahmed Ibrahim Awale Amazon.com;

Images, Texts and Artifacts Related to Ethnicity in Ancient Egypt

heads of foreigners from a royal statue, around 2900 BC

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia and John Baines of Oxford University wrote: “The interpretation of local or ethnic identities from material culture poses numerous problems. There were considerable regional differences in the production of art, forms of architecture, and burial practices, the extent of which varied from period to period. In most cases these probably do not relate to ethnicity, but an ethnic group often experiences some social pressure, such as status negotiation either within the group or in relation to outsiders, in order to differentiate itself through its material culture. In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.) and Second Intermediate Period, the distinctive burials and pottery assemblages of the Nubian C-Group, Pan-Grave, and Kerma cultures appear in cemeteries throughout Egypt. These burials disappear in the New Kingdom, in a development that may be due both to the Egyptian acculturation of these groups and to a broader trend for cultural homogeneity after the political reunification of Egypt, both within Egypt and progressively throughout the Nubian Nile Valley. Their disappearance does not in itself signify that the relevant ethnic groups ceased to distinguish themselves from the general Egyptian population. Thus the ethnonym “Medjay,” which is generally assumed to have designated the bearers of the Pan-Grave culture, remained the term for “policeman” throughout the New Kingdom, long after they had ceased to be archaeologically identifiable. Medjay may have constituted both a professional and an ethnic group within Egyptian society. Aspects of habitus, such as social uses of space or methods of food preparation, form another potential indicator of ethnic-group membership. For example, the prevalence of Nubian-form cooking pots at the Middle Kingdom Egyptian military settlement of Askut has been interpreted as an assertion of (female) Nubian ethnic identity in a context where (male) Egyptians were the dominant group. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, Norwich; John Baines, Oxford University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The existence of stereotypes for foreigners, especially in pictorial representation, may have made it possible for some elite individuals to present themselves with reference to their ethnic identity; however, scholars’ focus on identifying “foreigners” has meant that these individuals are often not considered as people displaying an ethnicity within Egyptian culture but as (recent) immigrants. One example from the 18th Dynasty is Maiherperi, who was given the rare privilege of burial in the Valley of the Kings, with high quality grave goods that must have been royal gifts. Maiherperi was a “child of the royal nursery” (Xrd n kAp) and held the title of “Fanbearer on the King’s Right,” probably under Thutmose III. In vignettes in his Book of the Dead papyrus, he is depicted with a dark brown skin color and, in one case, tightly curled, chin-length hair that conforms to the Egyptian topos for representing Nubians; his mummy wore a similarly styled wig. These features may depict an individual’s ethnic identity within the bounds of decorum and the Egyptian representational system, and Maiherperi himself may have had some control over how he was depicted, thus defining one element of difference about himself.

“A comparable example, also from the 18th Dynasty, is the stela of a man named Terer from el-Amarna. The stela shows Terer (perhaps Dalilu) and his wife Irbura, both of whom have names that are probably Canaanite. Terer/Dalilu is depicted with a stereotypical Near Eastern hairstyle, beard, and patterned kilt, and drinking through a straw. Irbura—for whom no equivalent female topos of an ethnic foreigner existed at the time—is shown in the manner of Egyptian women. Whether this couple were immigrants or belonged to a distinct ethnic group settled within Egypt cannot be established from the evidence of the stela alone. A different convention is visible on a late 12th-Dynasty stela from Dahshur, whose owner is captioned “The Nubian woman Ankhetneni” (NHsjt anxt-nnj) and wears a short wig. This is one of very few stelae belonging to women from the period, and its owner probably was of high status, perhaps a member of the royal court. As with Terer/Dalilu, even though Ankhetneni is shown with a distinctive, quite possibly Nubian wig type, it is impossible to say whether she was an ethnic Nubian.

“In a number of battle scenes from the Old Kingdom to the New Kingdom, the depiction of the young offspring of captured foreignersor immigrant groups, may reflect the enslavement of these groups. Although the scenes meet the requirements of state ideology, using the “foreigner” topos, they also suggest another form of settlement in Egypt that may have contributed to ethnic differentiation and the shaping of individual ethnic identities. Similarly, the ethnonym Aamu (aAmw), “Asiatic,” came to mean also “slave” in the Egyptian language.”

Ethnicity and Naming Practices in Ancient Egypt

Sea People

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia and John Baines of Oxford University wrote: “Personal names may give some insight into the configuration of ethnic groups in Egypt. Naming practices were complex, however, and many factors influenced the choice of name. The ascription of ethnicity by reference to personal names is far from straightforward, and from an early period, expressions like “Nubian” (NHsj) functioned both as identifiers and as personal names. As early as the Old Kingdom, a few subordinate figures in decorated tombs are captioned “Nubian” (Nhsj) and “Libyan” (7mHw). These may be instances of labeling rather than nomenclature, but at least one such figure has a name of un-Egyptian appearance. These people were presumably members of elite households—in some respects parallel with exotic individuals, such as dwarfs and hunchbacks, whom their patrons also displayed as members of their entourages. Whether these “Nubians” were immigrants or ethnic Nubians from groups resident in Egypt cannot be known. New Kingdom and later instances of the personal name Panehsy (PA-NHsj, literally “the Nubian”) occur so frequently as to suggest that not everyone bearing this name necessarily identified himself, or was identified by others, as Nubian (compare here the possible translation of the name of the 13th-Dynasty king Nehesy “[the] Nubian” as “the Fortunate One”). Moreover, Nubia itself was a large area within which several ethnic groups were almost certainly present. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, Norwich; John Baines, Oxford University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Personal names attested from the Middle Kingdom include numerous examples that are not of Egyptian type, many of them referring to specific ethnic or regional backgrounds or combined with designations such as aAm “Asiatic”. These form an appreciable percentage of the total number of names known from the period. Thomas Schneider posits that those who immigrated, whether voluntarily or through forced migration, became quite rapidly acculturated, and as he notes, names alone are not a good indication either of ethnicity or, where of purely Egyptian type, of complete assimilation. Ethnicity is thus very difficult to identify in available sources, and it could have endured for generations or centuries while remaining invisible to modern research.

“The fact that individuals with non-Egyptian personal names attained the highest ranks in Egyptian society, especially in the New Kingdom and later, may suggest that some of them were not foreigners or immigrants but members of resident ethnic groups, perhaps ultimately descended from immigrants. The case of Maiherperi, introduced above, also exemplifies the potential of personal names as evidence for ethnic group membership. Meaning “the Lion on the Battlefield” (MAj Hr Prj), Maiherperi’s name points to a change of status during life, because it is an epithet of praise relating to the king that has parallels in the names of other high officials with possible foreign origin or Nubian or Asiatic ethnicity, attested from the same generation. One such example is Paheqamen, “the Ruler Endures” (PA 1qA Mn), who was chief architect and chief of the treasury during the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. Paheqamen bore the alternate name Benya, which is non- Egyptian, perhaps Semitic; the names of his parents are also of Syro-Palestinian origin. Leahy describes Benya/Paheqamen’s Theban tomb inscriptions as “reticent” about his past, but like Maiherperi, Benya/Paheqamen was a “child of the royal nursery” (Xrd n kAp). Two men of the reign of Amenhotep III who were named Heqareshu and Heqaerneheh who bore the same title and are known from the First Cataract may have been of Nubian extraction . Their contemporary, the vizier Aperel, also bore the title and had a “foreign” name; although his tomb at Saqqara is known, it does not mention his parents. The presence of ethnic foreigners in the entourage of kings has many parallels in other cultures, especially as military personnel, and affiliation with the kap (nursery) may have been one mechanism to facilitate this. Members of ethnic groups settled in Egypt might also have found royal favor, although it is difficult to evaluate the significance of this when it occurs over a long period of time. Throughout the Ramesside Period, for instance, about a quarter of the individuals who bore the title “royal butler” have foreign- sounding names, and one—Ramessessemperre, also known as Benazu—has a double name, plus a father whose name is of Syro-Palestinian origin.

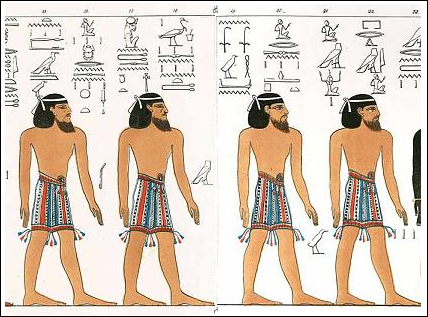

Canaanites from present-day Israel and Palestine

“Individual personal names cannot be taken as the sole direct evidence for ethnic identity. At Deir el-Medina in the New Kingdom, the presence of at least 17 individuals with possible Libyan names, such as Kel (with variants), has been interpreted as proof of an ethnic or immigrant community, but uncertainty surrounding the reading and interpretation of such names favors a cautious approach. Many of these people had parents or grandparents with Egyptian names, suggesting either that overt assimilation was reversed among later generations within ethnic groups or that the names came to be widely adopted. Similarly, the names of many New Kingdom royal women are non-Egyptian, and while some of these were foreign women who moved to Egypt for diplomatic marriages, others may have belonged to ethnic groups within the population of Egypt, and thus were not “foreign” at all.

“The Wilbour Papyrus from the reign of Ramesses V attests the widespread presence of people identified as Sherden, one of the ethnic groups associated with the “Sea Peoples,” settled in a region of Middle Egypt. Sherden also appear as witnesses in a document relating to the local Egyptian military in the reign of Ramesses XI, two generations later. From the same period come mentions in administrative documents of “foreigners” (probably to be read aAw), many of whom bear ordinary Egyptian names. This term seems to designate people who were not immigrants but were perhaps descended from them. Because it is unspecific, it does not have the appearance of an “ethnic” designation, but it might have been understood as such by the actors. Be that as it may, these people seem to belong to the ordinary population and not to form a category that is set apart in any functional way.

“The dynasties of kings with ethnic Libyan names who came to power in the Third Intermediate Period render visible the presence within Egypt of ethnic diversity. It has been suggested that these rulers, their associates, and their approach to political organization were distinctive due to their ethnic-group memberships, and that the retention of Libyan names may express a wish to assert Libyan ethnicity (on Libyan political structure). The question is to what extent membership of any of the various Libyan ethnic groups (Libu, Meshwesh, Tjemhu, etc.) was marked or recognized in Egyptian society, given that Libyans had been settled in the country for many generations. The attested iconographic topos for male Libyans as foreigners—beards, ostrich feather headbands, patterned garments—is attested mainly from the New Kingdom, when these people were depicted mainly as enemies. It was not deployed as a self-image for the ethnic Libyan rulers of the Third Intermediate Period, for example, but these rulers and other Libyan elites in Egypt used names and titles that identified them as Libyan. In this instance it seems that elements that had been integrated into Egyptian-language practices were appropriate markers for members of Egyptian society who exploited their ethnicity within the ruling group.

“In the Late Period (712–332 B.C.), internationalism, migration, and trade are especially well documented, and immigration from Thrace and the Greek cities of Anatolia was facilitated by the establishment of Naukratis (attributed to the reign of Psammetichus I) and the use of Greek mercenaries, first against Nubia (Psammetichus II) and later against Persian rule. The descendants of Greek immigrants took Egyptian names and operated within Egyptian cultural practices: a dark stone anthropoid sarcophagus is inscribed for the deceased Wahibraemhat, whose ethnic heritage emerges in the Greek names of his parents, Alexikles and Zenodote, transcribed into hieroglyphs. One of the possible markers of ethnicity—language difference—may have worked against acculturation for some ethnic groups, though such boundaries remain highly permeable. The Carian community established at Memphis, for instance, inscribed Carian and Egyptian in parallel on a series of sixth- century B.C. tombstones, which also combined Greek and Egyptian visual forms.”

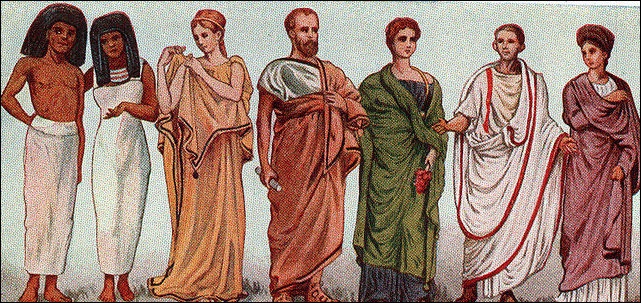

Nubians, Philistine, Amorite, Syrian and Hittite

Ethnicity in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia and John Baines of Oxford University wrote: “Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt, in 332 B.C., precipitated a period of mass immigration. Peaking in the third century B.C., immigration from the Mediterranean, the Black Sea coast, Asia Minor, and the Near East may have numbered into the hundreds of thousands and included foreign slaves and prisoners of war as well as economic migrants and military veterans. In Greek and Demotic sources, almost 150 different ethnic labels attest to the scale and geographic range of immigration and ethnic-group settlement. Many Greek-speaking immigrants did not remain separate from the existing population. Men like the Greek cavalry officer Dryton married into Egyptian families, and an Egyptian priest named Horemheb, who lived at Naukratis during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, seems to have had a Greek father and an Egyptian mother. Acculturation during the Ptolemaic Period thus operated in two directions: Greeks learned to speak Egyptian and adopted Egyptian practices and beliefs, while Egyptians acquired Greek literacy in order to succeed in the changing social and political climate. Examples of these processes are attested up to the highest levels in society, including a “Greek” chief financial officer named Dioskourides who was buried in an Egyptian sarcophagus (second century B.C.), as well as significant interaction between the indigenous Egyptian high priests of Memphis and the Ptolemaic ruling house. Other ethnic groups may have maintained more closed boundaries, such as Jewish communities, or the Persian residents implied by a third-century B.C. stela from Saqqara, inscribed in Demotic for a man named Khahap, “leader of the Medes”. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, Norwich; John Baines, Oxford University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Although the Ptolemaic administration did not define “Greek” and “Egyptian” in legal terms, Demotic documents of the period make use of the ethnic label “Greek” (Wjnn) or “Greek, born in Egypt” (Wjnn ms n Kmj) to help identify individuals, and perhaps to indicate an individual’s native language. Over time, increasing bilingualism, the process of acculturation across the permeable group boundaries, and the prevalence of Greek administrative and cultural institutions encouraged the formation of a social elite recognized as Greeks or Hellenes, which in some ways operated like an ethnic group. This “hellenized” group was not a legally defined category in Ptolemaic times, but as Goudriaan observed, its existence set a precedent that was exploited by the Roman administration, after the annexation of Egypt in 30 B.C..

“In Roman Egypt, “Egyptian” became a defined category for taxation purposes (Egyptians paid the poll tax at full rate), alongside categories for Roman citizens, Alexandrian citizens, citizens of the other Greek cities (Naukratis, Ptolemais, and later Antinoopolis), Jews, and metropolites. These last, who paid reduced poll tax, were residents of the nome capitals (metropoleis), and their status as members within the metropolite category had to be proved through paternal and maternal descent. Censuses carried out under Augustus may have identified the “hellenized” elites of the late Ptolemaic Period and codified their membership, thus turning a quasi-ethnic group into a hereditary status group. Other individuals in Roman Egypt may have self- identified as “Greeks,” but without metropolite (or gymnasial) membership, they would not have enjoyed any recognition as such for legal or taxation purposes. A collection of statutes known as the Gnomon of the Idios Logos underscores the Roman administration’s concern with status and group membership: according to one stipulation in the Gnomon, a child born to a Roman citizen and an Egyptian, as defined by Roman law, would inherit the status of the lower-ranking parent.

“Although Greek was the language of the imperial administration, the persistence of bilingualism in Roman Egypt is attested not only by the use of Demotic but also by the development of Coptic. As Jacco Dieleman observes, Greek was “the language of upward social mobility”; the Egyptian language, as well as other cultural forms, changed both in relation to it and depending on the circumstances and interests of individuals and of social groups. The indigenous language, which remained remarkably free of Greek loan-words in the Demotic script, was used for a rich vein of literary and religious texts. The Roman administration did not accept Demotic for official uses such as legal contracts, but more modest documentary texts reveal that even in “hellenized” areas like the Fayum, temple personnel used Demotic for administrative purposes among themselves. Colloquial, spoken Egyptian probably differed from Demotic in extent of Greek influence and in relation to the speech strategies that its users adopted. For bilingual Greek and Egyptian speakers, language will have been situational and so may have contributed to ethnic or cultural identity.

“As in earlier periods, naming patterns may also point to ethnic difference; however, factors such as gender influenced the choice of personal names. In the family of Soter from Thebes, dated to the first and second centuries CE, daughters tended to have Egyptian names while the sons bore Greek, or dual Greek and Egyptian, names. If these individuals were attested only in isolation, without information about their parents and siblings, the males might be taken for ethnic “Greeks” and the females for “Egyptians,” rather than members of an Egyptian family that aspired, for their men, to the advantages offered by the status of being “Greek”.

“By the Late Roman Period, the negotiation of ethnic and cultural group identities encompassed religious affiliation as well as factors such as language use, exemplified by the case of Philae (Syene). Blemmyes and Nubians in Greek and Demotic texts point to the activities of groups that were perceived as ethnic others, but on what basis they were perceived as such, and how these groups identified themselves, is unknown. The boundaries between the groups active in the region were as complex and changeable as the pattern of religious practice and language.”

Foreign Communities in The Ancient Egyptian Empire

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “More elusive communities comprised Egyptians who settled and lived in the Levant following the imperial expansion of the New Kingdom. A number of these individuals may have constituted an Egyptian “trading diaspora” involved in commerce and other activities. In other cases they were soldiers, administrators, or simply settlers whose culinary tastes (such as the consumption of Nile perch) and toilette customs make them visible in the archaeological record and distinguishable from the local, Levantine populations. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The Story of Sinuhe and The Tale of Woe , whether fictional in nature, reveal nevertheless the anxieties and expectations of exiles living outside the Nile Valley and the importance they attached to the precise adherence to Egyptian customs regard ing food and the care of the body. The adaptability exhibited by the inhabitants of the Nubian fortresses, surely related to the non-institutional nature of their activities (mainly trade), explains why the fortress dwellers thrived both when the Egyptian monarchy was strong and centralized and when it collapsed. This could also explain why the fortresses were often surrounded by non-walled settlements in which a mixed population of Nubians and Egyptians lived and traded: Egyptian “colonists” apparently had little to fear from their Nubian neighbors. The Semna dispatches as well as royal inscriptions record the arrival at the fortresses of small Nubian trading caravans, while the discovery of execration texts, accompanied by human sacrifices, close to the “open city” northeast of the fortress of Mirgissa provides some clues about a gloomier aspect of the trading activities, wherein bloody rituals were conducted to ensure protection from danger.

“Mention should additionally be made of the Middle Kingdom Egyptian fortresses in Nubia and of the Old Kingdom settlement at Balat, in the Dakhla Oasis. We observe that administrative practices and formal hierarchies were quite visible in these specialized communities when the central government was strong, and that, moreover, when the central government collapsed, these communities continued to thrive, revealing that, beyond the ir official function, their inhabitants enjoyed a high degree of autonomy, irrespective of any central instruction or support.”

Integration of Diverse Communities in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “The integration of different communities in cosmopolitan settings, such as capital cities and probably also in lesser cities” is an interesting topic. “One is reminded of the famous stela depicting an Asiatic soldier drinking beer in the company of his (apparently) Egyptian wife and young son. Some documents refer to Asiatics as prisoners of war or slaves in the hands of institutions. But in other instances they appear to have been well integrated in pharaonic society, married Egyptians, performed various trad es, bore Egyptian titles occasionally and displayed their foreign origin in their otherwise fully Egyptian monuments. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Thus, for instance, Perseneb, an attendant of the palace, bore an Egyptian name, but his grandmother, his two sisters, and other members of his household were presented in his monuments as Asiatics (aAmw ), while his niece bore a non-Egyptian name. The Wilbour Papyrus provides evidence of foreigners who had become soldiers a nd officials in the Egyptian army and who enjoyed considerable wealth as holders of substantial plots of land. There is, furthermore, evidence of military colonies where Asiatic soldiers were settled in Ramesside times, especially in Middle Egypt. We are, however, unaware of whether Asiatics living in Egyptian cities settled in separate neighborhoods or, on the contrary, whether they mingled with their Egyptian neighbors in the same urban sectors.

“Bietak has recently shown that Egyptians living in Avaris during the Hyksos Period occupied a particular area of the city, judging from the material evidence: neither toggle-pins nor intramural burials have been found there (two typical Canaanite ethnic markers), while these items were prese nt in neighboring quarters. It might then be inferred that this part of the city was inhabited by an Egyptian community. Other foreign settlers entering the Nile Valley seem to have preferred (or been forced into) a segregated life according to the funerary evidence.

“Such is the case regarding the Pan-Grave Nubian cemeteries, dating to the first centuries of the second millennium BCE, recovered in many localities of Upper Egypt. It does appear that people from different origins co existed at specific sites such as at harbors and mining centers. Slaves and serfs arrived in Egypt in substantial numbers during some periods. Usually employed in dome stic activities in private households or as specialized workers (weavers, cultivators, gardeners) in institutions, they may have constituted another social sector in cities and in the rural domains of the nobility. It is unknown to what extent the mix of s laves, soldiers, and traders from different countries may have contributed to create some sort of “creole” culture in those places. Their presence may have introduced foreign rituals and fashions that exerted some influence on their humbler Eg yptian neighbors, or conversely may have strengthened a sense of Egyptian-ness among the Egyptian population.”

Isis cult ceremony

Cult Centers Bring Diverse People Together in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: ““The importance of the cult of Hathor was, in fact, crucial to promoting trust and facilitating the coexistence of people from diverse origins working together at special sites, such as mines and harbors . The mining site of Serabit el-Khadim in Sinai reveals, for instance, that Egyptians, Canaanites, peoples from the eastern margins of the Delta, and Bedouin participated together in the exploitation and transport of the mineral ores. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Hathor’s sanctuary there has preserved abundant epigraphic, iconographic, and cult evidence of the interaction of these populations and thus helps balance the typical image of foreigners as a menace to Egypt or as poor, wandering nomads seeking to enter the Nile Valley. To the contrary, this small cosmopolitan micro-cosmos reveals that Canaanite warriors helped maintain the security of the site and that “marginal” populations were crucial in the organization of logistics (including caravans of donkeys); indeed a foreign leader is depicted with the paraphernalia proper to his rank, sitting on a donkey. Not surprisingly, it was at this cultural crossroad that a new form of writing, Proto-Sinaitic, flourished. Ultimately, the site of Serabit el-Khadim helps us understand how other specialized communities operated within Egypt, examples of which include Elephantine, Tell el-Dab aa, the Nubian fortresses of the Middle Kingdom, and other trading communities where peoples from diverse origins (Nubians, Asiatics, Libyans, Egyptians, desert dwellers) coexisted and worked together. Their cultural practices (burials) and markers (pottery, body ornaments, even cloth) attest their presence there and defy stereotypical interpretations of their roles. Not every Nubian living in Egypt was necessarily a mercenary, nor an Asiatic, slave, or trader.

“Other sorts of specialized communities provide evidence of their role and social composition with more administrative accuracy. The verso of papyrus British Museum 10068 lists people living in a “village” in the area of the Qurna temple of Sety I, the Ramesseum, and the mortuary temple of Ramesses III. Given the location of this settlement, it is likely that many (if not all) of the personnel recorded were at the service of these cult centers. Thus the document includes 25 wab-priests and seven god’s fathers, as well as several high officials (like Pwer ‛ o, the mayor of Western Thebes who played an important role in the tomb robbery affairs), craftsmen and laborers, herdsmen, cultivators, and “middle rank” citizens. In other words, officials with important duties at Thebes, members of the clergy, and crafts men and workers involved in the activities and supply of the temples occupied this area.”

Herodotus on People in the Nile Delta

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “All these are the customs of Egyptians who live above the marsh country. Those who inhabit the marshes have the same customs as the rest of Egyptians, even that each man has one wife just like Greeks. They have, besides, devised means to make their food less costly. When the river is in flood and flows over the plains, many lilies, which the Egyptians call lotus, grow in the water. They gather these and dry them in the sun; then they crush the poppy-like center of the plant and bake loaves of it. The root of this lotus is edible also, and of a sweetish taste; it is round, and the size of an apple. Other lilies grow in the river, too, that are like roses; the fruit of these is found in a calyx springing from the root by a separate stalk, and is most like a comb made by wasps; this produces many edible seeds as big as olive pits, which are eaten both fresh and dried. They also use the byblus which grows annually: it is gathered from the marshes, the top of it cut off and put to other uses, and the lower part, about twenty inches long, eaten or sold. Those who wish to use the byblus at its very best, roast it before eating in a red-hot oven. Some live on fish alone. They catch the fish, take out the intestines, then dry them in the sun and eat them dried. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Fish that go in schools are seldom born in rivers; they are raised in the lakes, and this is how they behave: when the desire of spawning comes on them, they swim out to sea in schools, the males leading, and throwing out their milt, while the females come after and swallow and conceive from it. When the females have grown heavy in the sea, then all the fish swim back to their own haunts. But the same no longer lead; now the leadership goes to the females. They go before in a school as the males had, and now and then throw off some of their eggs (which are like millet-seeds), which the males devour as they follow. These millet-seeds, or eggs, are fish. The fish that are reared come from the eggs that survive and are not devoured. Those fish that are caught while swimming seawards show bruises on the left side of their heads; those that are caught returning, on the right side. This happens because they keep close to the left bank as they swim seawards, and keep to the same bank also on their return, grazing it and keeping in contact with it as well as they can, I suppose lest the current make them miss their way. When the Nile begins to rise, hollow and marshy places near the river are the first to begin to fill, the water trickling through from the river, and as soon as they are flooded, they are suddenly full of little fishes. Where these probably come from, I believe that I can guess. When the Nile falls, the fish have dropped their eggs into the mud before they leave with the last of the water; and when in the course of time the flood comes again in the following year, from these eggs at once come the fish.

“So much, then, for the fish. The Egyptians who live around the marshes use an oil drawn from the castor-berry, which they call kiki. They sow this plant, which grows wild in Hellas, on the banks of the rivers and lakes; sown in Egypt, it produces abundant fruit, though malodorous; when they gather this, some bruise and press it, others boil after roasting it, and collect the liquid that comes from it. This is thick and useful as oil for lamps, and gives off a strong smell.

“Against the mosquitos that abound, the following have been devised by them: those who dwell higher up than the marshy country are well served by the towers where they ascend to sleep, for the winds prevent the mosquitos from flying aloft; those living about the marshes have a different recourse, instead of the towers. Every one of them has a net, with which he catches fish by day, and at night he sets it around the bed where he rests, then creeps under it and sleeps. If he sleeps wrapped in a garment or cloth, the mosquitos bite through it; but through the net they absolutely do not even venture.”

Herodotus on the Colchians

The Colchians are people from modern-day Georgia. Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “For it is plain to see that the Colchians [people from the west Caucasus) are Egyptians; and what I say, I myself noted before I heard it from others. When it occurred to me, I inquired of both peoples; and the Colchians remembered the Egyptians better than the Egyptians remembered the Colchians; the Egyptians said that they considered the Colchians part of Senusret' army. I myself guessed it, partly because they are dark-skinned and woolly-haired; though that indeed counts for nothing, since other peoples are, too; but my better proof was that the Colchians and Egyptians and Ethiopians are the only nations that have from the first practised circumcision. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“The Phoenicians and the Syrians of Palestine acknowledge that they learned the custom from the Egyptians, and the Syrians of the valleys of the Thermodon and the Parthenius, as well as their neighbors the Macrones, say that they learned it lately from the Colchians. These are the only nations that circumcise, and it is seen that they do just as the Egyptians. But as to the Egyptians and Ethiopians themselves, I cannot say which nation learned it from the other; for it is evidently a very ancient custom. That the others learned it through traffic with Egypt, I consider clearly proved by this: that Phoenicians who traffic with Hellas cease to imitate the Egyptians in this matter and do not circumcise their children.

“Listen to something else about the Colchians, in which they are like the Egyptians: they and the Egyptians alone work linen and have the same way of working it, a way peculiar to themselves; and they are alike in all their way of life, and in their speech. Linen has two names: the Colchian kind is called by the Greeks Sardonian ; that which comes from Egypt is called Egyptian.”

Nubia and Ethiopia

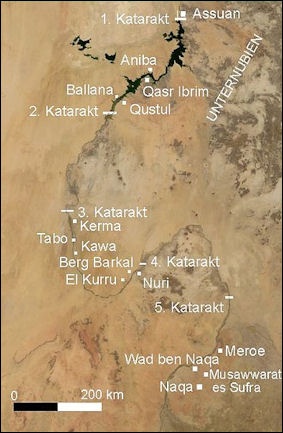

Nubia

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: Nubia was a region south of Egypt, which was divided by the Nile nearest the 2nd Cataract. The products of Nubia and Kush added greatly to the wealth of Egypt, particularly by providing gold, ivory, ebony, cattle, gums and semi-precious stones. Cattle were one of the major contributions made by Nubia suggesting that grasslands were more extensive in the time of the Old Kingdom. In addition, the Nile Delta below Memphis has always been one of great fertility, flanked on its eastern and western borders by wide meadowlands where goats, sheep and cattle were raised. The fertility of Nubia and it's products enriched both Egyptian and Nubian cultures which lived along the Nile. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

In some ancient texts Ethiopians are described as living south or Egypt rather than Nubians. It seems likely that the authors meant Nubians or were reporting on Nubians and Ethiopians are generally describing black Africans that lived south of Egypt. During the 25th Dynasty, Egypt was led by three Nubian list three Ethiopian kings form the twenty-fifth dynasty, Sabacon, Sebichos, and Taracos (the Tirhaka of the Old Testament).

The main accounts of Ancient Nubia and Ethiopia from classical sources are a text on the Aspalta as King of Kush, c. 600 B.C.; Herodotus, The Histories, c. 430 B.C., Book III; Strabo: Geography, A.D. 22, XVI.iv.4-17; XVII.i.53-54, ii.1-3, iii.1-11; Acts of the Apostles 8:26-39; Dio Cassius: History of Rome, c. A.D. 220, CE, Book LIV.v.4-6; Inscription of Ezana, King of Axum, c. A.D. 32; Procopius of Caesarea: History of the Wars, c. A.D. 550, Book I.xix.1, 17-22, 27-37, xx.1-13. There are also accounts by Pliny the Elder, Claudius Ptolemaeus, and the Periplus but they used the same source that Strabo did. There is also an account by Diodorus Siculus but is virtually the same as Strabo’s. [Source: Paul Halsall, Forham University]

Herodotus and Strabo on Nubia and Ethiopia

Herodotus wrote in Book 3 of “Histories”: “I went as far as Elephantine [Aswan] to see what I could with my own eyes, but for the country still further south I had to be content with what I was told in answer to my questions. South of Elephantine the country is inhabited by Ethiopians...Beyond the island is a great lake, and round its shores live nomadic tribes of Ethiopians. After crossing the lake one comes again to the stream of the Nile, which flows into it. ...After forty days journey on land along the river, one takes another boat and in twelve days reaches a big city named Meroë, said to be the capital city of the Ethiopians. The inhabitants worship Zeus and Dionysus alone of the Gods, holding them in great honor. There is an oracle of Zeus there, and they make war according to its pronouncements, taking it from both the occasion and the object of their various expeditions. . . .After this Cambyses [King of Persia] took counsel with himself, and planned three expeditions. One was against the Carthaginians, another against the Ammonians, and a third against the long-lived Ethiopians, who dwelt in that part of Libya which borders upon the southern sea. . . while his spies went into Ethiopia, under the pretense of carrying presents to the king, but in reality to take note of all they saw, and especially to observe whether there was really what is called "the table of the Sun" in Ethiopia. Now the table of the Sun according to the accounts given of it may be thus described: It is a meadow in the skirts of their city full of the boiled flesh of all manner of beasts, which the magistrates are careful to store with meat every night, and where whoever likes may come and eat during the day. The people of the land say that the earth itself brings forth the food. Such is the description which is given of this table. [Source: Herodotus, The History, trans. George Rawlinson (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862)

Strabo wrote in “Geography” (A.D. 22): “Egypt was from the first disposed to peace, from having resources within itself, and because it was difficult of access to strangers. It was also protected on the north by a harborless coast and the Egyptian Sea; on the east and west by the desert mountains of Libya and Arabia, as I have said before. The remaining parts towards the south are occupied by Troglodytae, Blemmyae, Nubiae, and Megabarae Ethiopians above Syene. These are nomads, and not numerous nor warlike, but accounted so by the ancients, because frequently, like robbers, they attacked defenseless persons. Neither are the Ethiopians, who extend towards the south and Meroë [ancient capital of Kush on the east bank of the Nile about 200 kilometers north-east of Khartoum in present-day Sudan] numerous nor collected in a body; for they inhabit a long, narrow, and winding tract of land on the riverside, such as we have before described; nor are they well prepared either for war or the pursuit of any other mode of life. [Source: Strabo, “The Geography of Strabo:” XVI.iv.4-17; XVII.i.53-54, ii.1-3, iii.1-11, translated by H. C. Hamilton, esq., & W. Falconer (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857), pp. 191-203, 266-272, 275-284]

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT SOURCES ON NUBIA AND ETHIOPIA africame.factsanddetails.com ; LIFE OF THE ANCIENT NUBIANS: LANGUAGES, RELIGION AND TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024