HAIR IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Images from Ancient Egyptians usually depict people as having black hair but that wasn’t always the case. The mummy of Ramses II has fine silky yellow hair. The mummy of the wife of King Tutankhamen has auburn hair. The tomb of the wife of Zoser, the builder of the first pyramid in Egypt, has a painting of her showing her with reddish-blond hair. Queen Hetop-Heres II, of the Fourth Dynasty, the daughter of Cheops, the builder of the great pyramid, is shown in the colored bas reliefs of her tomb to have been a distinct blonde. Her hair is painted a bright yellow stippled with little red horizontal lines.

According to Archaeology magazine: In a study of more than 100 skulls excavated from the site of Amarna, some 28 had remains of preserved hair, which is allowing a unique look into hairstyles and ethnicity in this part of ancient Egypt 3,300 years ago. Among them were several with extensions braided into the natural hair, including one on which there were approximately 70 extensions fastened in different places and layers. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2015]

The earliest combs are believed are believed to be fish bones. The earliest man-made combs were discovered in 6000-year-old Egyptian tombs. Some had single rows of teeth. Some had double rows of teeth.

Baldness was looked down upon. Chopped lettuce and ground-up hedgehog spines were applied to the scalp as a remedy for baldness. Other cultures have tried everything from camel dung to bear grease to achieve the same result. A male body from a working class cemetery in Hierakonpolis dated around 3500 B.C. had a sheepskin toupee used to hide a bald spot

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Historical Wig Styling: Ancient Egypt to the 1830s” by Allison Lowery (2019) Amazon.com;

“Construction of an Ancient Egyptian Wig in the British Museum” by J.Stevens Cox Amazon.com;

“Sacred Luxuries: Fragrance, Aromatherapy, and Cosmetics in Ancient Egypt”

by Lise Manniche and Werner Forman (1999) Amazon.com;

”A Catalogue of Egyptian Cosmetic Palettes in the Manchester University Museum Collection” by Julie Patenaude and Garry J. Shaw (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian Costume” by Mary Galway Houston (1920) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Jewelry” by Carol Andrews (1991) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“Healthmaking in Ancient Egypt: The Social Determinants of Health at Deir El-Medina

by Anne E. Austin (2024) Amazon.com;

“In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians” by Charlotte Booth (2019) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Hairstyles in Ancient Egypt

Egyptian men were usually clean shaven and sported both long and short hair styles. Men wore their hair long; boys had their heads shaved except for a lock of hair above their ear. A male body from a working class cemetery in Hierakonpolis dated around 3500 B.C. had a well trimmed beard.

Ancient Egyptians sported curls, braids, waves, twists, wigs and extentions, They dyed their hair and cut it short like U.S. Marines. Kozue Takahashi of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “Egyptians threaded gold tubes on each tress, or strung inlaid gold rosettes between vertical ribs of small beads to form full head covers. The also used combs, tweezers, shavers and hair curlers. Combs were either single or double sided combs and made from wood or bone. Some of them were very finely made with a long grip. Combs were found from early tomb goods, even from predynastic times. Egyptians shaved with a stone blade at first, later with a copper, and during the Middle Kingdom with a bronze razor.” [Source: Kozue Takahashi, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

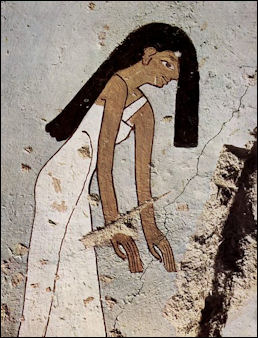

Women sometimes wore long things in their hair. A female body from a working class grave dated around 3500 B.C. had evidence of hair coloring (henna was used to color grey hair) and hair weaving (locks of human hair were tied to natural objects to produce an elaborate beehive hairdo). A grave in the worker’s cemetery at Hierakonpolis revealed a woman in her late 40s or early 50s with a Mohawk. Egyptians darkened grey hair with the blood of black animals and added false braids to their own hair.

Scholars often use hairstyles to date objects and even use them to determine foreign influences. .“There is evidence of influence from other cultures on Egyptian hairstyles. One example is the cultural union of the Roman Empire and the Egyptian empire. There is evidence of a female mummy wearing a typically Roman hairstyle yet the iconography on her death mask was plainly Egyptian. At Tell el-Daba in Egypt, there was a statue portrayed wearing a mushroom hairstyle that was typical of Asiatic males. There is a statue of young woman in the Ptolemaic period (304–30 B.C.) exhibiting a typical Nubian hairstyle consisting of five small clumps of hair. +\

Facial Hair and Artificial Beards in Ancient Egypt

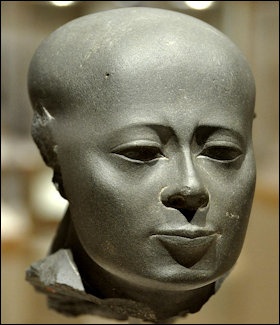

Egyptian men were generally clean-shaven and priests like the one above often shaved their heads

Cheryl Dawley of Minnesota State University, Mankato, wrote: “The Egyptians thought that an abundance of facial hair was a sign of uncleanliness and personal neglect. An exception to this was a man's thin mustache or goatee. There was no soap so an oil or salve was probably used to soften the skin and hairs of the area to be shaved. Tweezers with blunt or sharp ends were used for removing individual facial hairs.” [Source: Cheryl Dawley, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

In all epochs of Egyptian history it is very rarely we find that a gentleman wears even a small moustache, shepherds alone and foreign slaves let their beards grow — evidently to the disgust of all cleanly men. Yet in Egypt the notion that the beard was the symbol of manly dignity, had survived from the most primitive ages. If therefore on solemn occasions the great lords of the country wished to command respect, they had to appear with beards, and as the natural beard was forbidden, there was no other course but to fasten on an artificial one underneath the chin. This artificial beard is really the mere suggestion of a beard, it is only a short piece of hair tightly plaited, and fastened on by two straps behind the ears. ' Every one would willingly have done without this ugly appendage; men of rank under the Old Kingdom put it on sometimes when they appeared in their great wigs on gala days, but they often left it off even on these occasions, and scarcely ever did one of them allow it to be represented on his portrait statue; he felt that it was disfiguring to the beauty of the face. These straps do not always appear on the sculptures; in spite of their absence, we nuist always regard these beards as artificial, as the same person is represented sometimes with, sometimes without, a beard. Even some queens are shown with a beard that perhaps was made of a mixture of black sheep's wool and human hair. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

It was more common under the Middle Kingdom and was worn even by the officials of the nomes and of the estates, though very seldom by those of more ancient times. Under the New Kingdom again it was seldom worn, such as none of the courtiers of Akhenaten wear it; it was considered as a fashion of past days, and only appropriate for certain ceremonies. A longer form of the artificial beard belongs strictly to the royal dress, and though we find it occasionally worn by the nomarchs under the Middle Kingdom, it was as much an encroachment on the royal prerogative as the wearing of the Shendyt. Finally, the gods were supposed to wear beards of a peculiar shape; they were longer by two finger-breadths than those worn by men, they were also plaited like pigtails and bent up at the end.

Shaving in Ancient Egypt

Kozue Takahashi, of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “In ancient Egypt, men and women used to shave their heads bald replacing their natural hair with wigs. Egyptian women did not walk around showing their bald heads, they always wore the wigs. Head shaving had a number of benefits. First, removing their hair made it much more comfortable in the hot Egyptian climate. Second, it was easy to maintain a high degree of cleanliness avoiding danger of lice infestation. In addition, people wore wigs when their natural hair was gone due to old age. However, even though the Egyptians shaved their heads, they did not think the bald look was preferable to having hair.” [Source: Kozue Takahashi, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

“Priests were required to keep their entire bodies cleanly shaved. They shaved every third day because they needed to avoid the danger of lice or any other uncleanness to conduct rituals. This is the reason why priests are illustrated bald-headed with no eyebrows or lashes. +\

It has often been maintained that the ancient Egyptians shaved their heads most carefully, and wore artificial hair only. The following facts moreover are incontrovertible: we meet with representations of many smoothly shaved heads on the monuments, there are wigs in several museums," and the same person had his portrait taken sometimes with short, at other times with long hair. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Herodotus also expressly states of the Egyptians of his time that they shaved themselves from their youth up, and only let their hair grow as a sign of mourning. An unprejudiced observer will nevertheless confess, when he studies the subject, that the question is not so simple as it seems at first sight. The same Herodotus remarks, for instance, that in no other country are so few bald heads to be found, and amongst the medical prescriptions of ancient Egypt are a number of remedies for both men and women to use for their hair. Still, more important is it to observe that in several of the statues belonging to different periods little locks of natural hair peep out from under the edge of the heavy wigs. We must therefore conclude that when a man is said to be shaven we are as a rule to understand that the hair is only cut very short, and that those persons alone were really shaven who are represented so on the monuments, viz, the priests of the New Kingdom.

Hairstyles and Identify in Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, hair styles were often expressions of identity, religious position and class. Style and class were just as important in the afterlife. A study of 18 mummies by the University of Manchester revealed that many had their hair coated wtih a fatty substance. [Source: National Geographic]

Kozue Takahashi of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “For ancient Egyptians, appearance was an important issue. Appearance indicated a persons status, role in a society or political significance. Egyptian hairstyles and our hairstyles today have many things in common. Like modern hairstyles Egyptian hairstyles varied with age, gender and social status. [Source: Kozue Takahashi, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Children had unique hairstyles in ancient Egypt. Their hair was shaved off or cut short except for a long lock of hair left on the side of the head, the so-called side-lock of youth. This s-shaped lock was depicted by the hieroglyphic symbol of a child or youth. Both girls and boys wore this style until the onset of puberty. Young boys often shaved their heads, while young girls wore their hair in plaits or sometimes did up their hair in a ponytail style, hanging down the center of the back. Young girl dancers used to wear long thick braided ponytails. The edge of the tail was either naturally curled or was enhanced to do so. If the ponytail was not curled at the end, it was weighted down by adornments or metal discs. +\

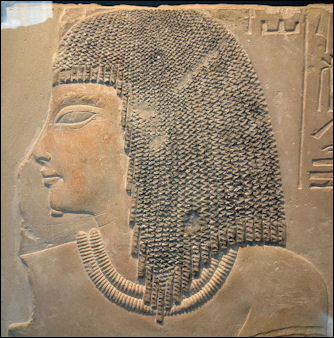

“Egyptian men typically wore their hair short, leaving their ears visible. Men often kept these hairstyles until their hair began to thin with advancing age. Another hairstyle for men was distinctive short curls covering the ears shaping a bend from temple to nape. It is doubtful that this hairstyle was natural. It was more likely a result of a process of hair curling that was done occasionally. +\

“Women's hairstyles were more unique than those of men. Women generally preferred a smooth, close coiffure, a natural wave and long curl. Women in the Old Kingdom preferred to have short cuts or chin length bobs. However, women in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) wore their hair long or touted a wig. Women tied and decorated their hair with flowers and linen ribbons. A stylized lotus blossom was the preferred adornment for the head. This developed into using coronets and diadems. Diadems made of gold, turquoise, garnet, and malachite beads were discovered on an ancient Egyptian body dating to 3200 B.C. Poorer people used more simple and inexpensive ornaments of petals and berries to hold their hair at the back. Children decorated their hair with amulets of small fish, presumably to protect from the dangers of the Nile. Children sometimes used hair-rings or clasps. Egyptians wore headbands around their heads or held their hair in place with ivory and metal hairpins. Beads might be used to attach wigs or hair extensions in place. +\

“Slaves and servants were not able to dress the same as Egyptian nobility. The way that they adorned their hair was quite different. Commonly, they tied their hair at the back of the head into a kind of loop. Another type of hairstyle was to tie it in eight or nine long plaits at the back of the head and to dangled them together at one side of the neck and face. +\

Wigs in Ancient Egypt

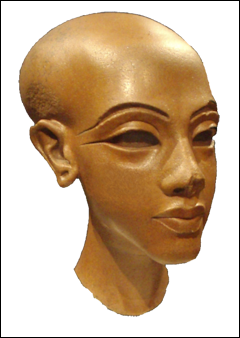

Wigs were popular in ancient Egypt as they were in ancient Mesopotamia, Crete, Persia and Greece. Egyptian ones were made from vegetable fiber such as linen, sheep wool, animal hair or human hair stiffened with beeswax. The earliest known ones date back to around 3000 B.C. Many ancient Egyptian wigs have survived in relatively good condition and several museums and universities have fine collections of them.

Wigs were worn at major festivals and events. Members of the upper classes possessed many wigs, elaborate double wigs with intricate braids and curls, curls kept in place with beeswax and hair bands ending in tassels. Most Pharaohs had short cropped hair. The head coverings you see on mummy cases and giant statues are the not headdresses or natural hair but wigs. Pharaohs wore false beards, with length indicating status. False beards were even popular with some Egyptian queens. During Nefertiti’s reign ordinary people started wearing wigs. A luxurious wig stiffened with beeswax was a powerful sexual symbol that linked the wearer to Hathor, the goddess of beauty.

Egyptian wigs tended to be helmet-like structures. Some were bright green, blue or red in color and some were adorned with precious metals and stones. Other were quite massive. One worn by Queen Isimkheb in 900 B.C., weighed so much she needed help from her attendants to stand up. Currently kept in the Cairo Museum, it was made entirely from brown human hair and held together by beeswax.

Cheryl Dawley of Minnesota State University, Mankato, wrote: “Wigs and hairpieces were also quite popular. They were quite elaborate and usually made of human hair. Other tools used in the beauty ritual that have been found include short fine tooth combs, hair pins, and a small bronze implement with a pivoting blade thought to be a hair curler.” [Source: Cheryl Dawley, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Kozue Takahashi, of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “Wigs were worn by men, women and children. They were adorned both inside and outside of the house. Egyptians put on a new wig each day and wigs were greatly varied in styles. The primary function of the wig was as a headdress for special occasions, such as ceremonies and banquets. [Source: Kozue Takahashi, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Wigs were curled or sometimes made with a succession of plaits. Only queens or noble ladies could wear wigs of long hair separated into three parts, the so-called goddress. However, they were worn by commoners in later times. During the Old and Middle Kingdom, there were basically two kinds of wig styles; wigs made of short or long hair. The former was made of small curls arranged in horizontal lines lapping over each other resembling roof tiles. The forehead was partially visible and the ears and back of the neck were fully covered. Those small curls were either triangular or square. The hair could be cut straight across the forehead or cut rounded. +\

“On the contrary, the hair from a long-haired wig hung down heavily from the top of the head to the shoulders forming a frame for the face. The hair was slightly waved and occasionally tresses were twisted into spirals. In the New Kingdom, people preferred wigs with several long tassel-ended tails, while shorter and simpler wigs became popular in the Amarna period. +\

Care of Wigs in Ancient Egypt

Wig cover from Tomb of

Three Minor Wives of Thutmose III

Kozue Takahashi, of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: ““Wigs were meticulously cared for using emollients and oils made from vegetables or animal fats. Those wigs that were properly cared for lasted longer than those without proper care. Although Egyptians preferred to wear wigs and took care of them, they also did take care of their natural hair. Washing their hair regularly was a routine for Egyptians. However, it is not known how frequently Egyptians washed their hair. [Source: Kozue Takahashi, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Wigs were scented with petals or piece of wood chips such as cinnamon. When wigs were not used, they were kept in special boxes on a stand or in special chests. When it was needed, it could be worn without tiresome combing. Wig boxes were found in tombs and the remnants of ancient wig factories have been located. Since it is believed that wigs were also needed for the afterlife, the dead were buried in the tombs with their wigs. +\

“Wigs were usually made from human hair, sheep's wool or vegetable fibers. The more it looked like real hair, the more expensive it was and the more it was sought after. Wigs of high quality were made only from human hair, while wigs for the middle class were made with a mix of human hair and vegetable fibers. The cheapest wigs were made fully from vegetable fibers. Both wig making specialists and barbers made the wigs and wig making was considered to be a respectable profession. It was one of the jobs available to women. People cut or shaved their hair by themselves or went to the barbers. A barbershop scene is depicted in the tomb of Userhet at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, where young men are forming a waiting line, sitting on the folding chairs and tripods while the barber is working. +\

Hair Treatments in Ancient Egypt

It is curious that, amongst this wig-wearing people, the doctor was especially worried about hair; men as well as women required of him that when their hair came out he should make it grow again, as well as restore the black color of youth to their white locks. We know not whether these Egyptian physicians understood this art better than their colleagues of modern times; at any rate they gave numberless prescriptions. For instance, as a remedy against the hair turning white the head was to be “anointed with the blood of a black calf that had been boiled with oil. " As a preservative against the same misfortune the “blood of the horn of a black bull," also boiled with oil, was to be used as an ointment. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

According to other physicians “the blood of a black bull that had been boiled with oil “was a real active expedient against white hair. In these prescriptions the black color of the bull's hair was evidently supposed to pass into the hair of the human being. We read also of the “fat of a black snake “being prescribed for the same object. When the hair fell out, it could be renewed by six kinds of fat worked up together into a pomade — the fat of the lion, of the hippopotamus, of the crocodile, of the cat, of the snake, and of the ibex. It was also considered as really strengthening to the hair to anoint it with the “tooth of a donkey crushed in honey. " On the other hand queen Shesh, the mother of the ancient King Pepe, found it advisable to take the hoof of a donkey instead of the tooth, and to boil it in oil together with dog's foot and date kernels, thus making a pomade. Those with whom this did not take effect might use a mixture of the excreta of gazelles, sawdust, the fat of the hippopotamus, and oil; or they might have recourse to the plant Degein, especially if they belonged to the community which believed in this plant as a universal remedy.

The physician however had not only to comply with the wishes of the lady who desired to possess beautiful hair herself, but unfortunately he had also to minister to the satisfaction of her jealousy against her rival with the beautiful locks. “To cause the hair of the hated one to fall out," take the worm 'an'art or the flower sepet, boil the worm or the flower in oil, and put it on the head of the rival. A tortoise-shell boiled, pounded, and mixed in the fat of a hippopotamus was an antidote against this cruel artifice, but it was necessary to anoint oneself with the latter “very very often “that it might be efficient.

Hair Dyes, Gels and Oils in Ancient Egypt

ancient Egyptian razor

Kozue Takahashi, of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: ““Egyptians used a material called henna (used for nails and lips, too) to dye their hair red. Scientific studies show that people used henna to conceal their gray hair from as early as 3400 B.C. Henna is still used today. There is a body of evidence from paintings that depict the existence of people with red hair, such as the 18th Dynasty Hunutmehet. She had distinctive red hair mentioned by Grafton Smith. [Source: Kozue Takahashi, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“Like today, ancient Egyptians were also facing the same problem of hair loss, and they wanted to maintain their youthful appearance as long as possible. There were many kinds of suggested remedies targeting primarily men. In 1150 B.C., Egyptian men applied fats from ibex, lions, crocodiles, serpents, geese, and hippopotami to their scalps. The fat of cats and goats was also recommended. Chopped lettuce patches were used to smear the bald spots to encourage hair growth. Ancient Egyptians also made use of something similar to modern aromatherapy. Fir oil, rosemary oil, (sweet) almond oil and castor oil were often used to stimulate hair growth. The seeds of fenugreek, that plant herbalists and pharmacologists still use today, was another remedy.” +\

According to Archaeology magazine: An analysis of 15 mummy hair samples shows just how important styling was more than 2,000 years ago. To understand how the complex hairdos were achieved and maintained after death, scientists studied coatings on the hair with electron microscopy and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. They found that the ancient Egyptians used a kind of fatty hair gel to keep their hair coiffed in both life and the afterlife. The absence of embalming materials in the hair suggests that it was covered during mummification. [Source: Archaeology magazine, January-February 2012]

Ancient Egyptian 'Hair Gel'

The ancient Egyptians styled their hair using a fat-based 'gel', an analysis of mummies announced in 2011 revealed. The researchers who did the study said that the Egyptians used the product to ensure that their hair stayed they way they wanted in both life and death. The study was led by Natalie McCreesh, an archaeological scientist from the KNH Centre for Biomedical Egyptology at the University of Manchester in Britain. Her team studied hair samples from 18 mummies. The oldest was around 3,500 years old, but most were excavated from a cemetery in the Dakhleh Oasis in the Western Desert, and date from Greco-Roman times, around 2,300 years ago. They include males and females ranging in age from 4 to 58 years old. Some were artificially mummified; others were preserved naturally by the dry sand in which they were buried. The results are published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.[Source: Jo Marchant, Nature, 19 August 2011]

Jo Marchant wrote in Nature: Microscopy using light and electrons revealed that nine of the mummies had hair coated in a mysterious fat-like substance. The researchers used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to separate out the different molecules in the samples, and found that the coating contained biological long-chain fatty acids including palmitic acid and stearic acid. McCreesh thinks that the fatty coating is a styling product that was used to set hair in place. It was found on both natural and artificial mummies, so she believes that it was a beauty product during life as well as a key part of the mummification process.

Jo Marchant wrote in Nature: Microscopy using light and electrons revealed that nine of the mummies had hair coated in a mysterious fat-like substance. The researchers used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to separate out the different molecules in the samples, and found that the coating contained biological long-chain fatty acids including palmitic acid and stearic acid. McCreesh thinks that the fatty coating is a styling product that was used to set hair in place. It was found on both natural and artificial mummies, so she believes that it was a beauty product during life as well as a key part of the mummification process.

“The resins and embalming materials used to prepare the artificially mummified bodies were not found in the hair samples, suggesting that the hair was protected during embalming and then styled separately. "Maybe they paid special attention to the hair because they realized that it didn't degrade as much as the rest of the body," says McCreesh. The product was found on both male and female mummies, showing that both sexes cared about their eternal hairdo.”

John Taylor, head of the Egyptian mummy collection at the British Museum in London, told Nature that Egyptian texts and art contain no mention of hair products, although ancient Egyptians are known to have used scented oils and lotions on their bodies. "The best clue comes from Egyptian wigs," says Taylor. "The hair is often coated with beeswax." Such wigs, which have been found in Egyptian tombs, would have been expensive and probably restricted to the nobility, says McCreesh. "The majority of the mummies I've looked at have their own hair," she says.

“The Egyptians might have also used beeswax on their own hair. The wax contains fatty acids such as palmitic acid, although McCreesh says that her results so far don't show any evidence of beeswax. "It was a fat, but we can't tell you what type of fat," she says. She points out that beeswax would be difficult to wash out of hair, compared to, say, animal fat. She now plans to analyse the samples further, to try to pin down the hair-gel recipe.

“The mummies' hairstyles varied, both long and short, with curls particularly popular; metal implements resembling curling tongs have been found in several tombs. Once the hair was styled, the fatty gunge would have held the individuals' curls in place. "You can almost imagine them when they were alive," says McCreesh, "tending their hair and putting their curls in."

Hair Extensions in Ancient Egypt

Wigs were very expensive. Hair extensions were a cheaper alternative and were often preferred because they could be tied up in the back. Sometimes they were used to enhance wigs as Egyptians regarded thick hair as the ideal. In 2014, scientists announced they had found an unmummified 3,300-year-old Egyptian with a complex hairdo that included 70 different extensions. [Source: Rachel Feltman, Washington Post, September 17, 2014 ==]

.jpg)

ancient Egyptian hair pieces The hairdo was likely styled after death, and was held in place with animal fat. Archaeologist Jolanda Bos told Live Science that the woman probably used extensions in her day-to-day life — but we just can't be sure. "Whether or not the woman had her hair styled like this for her burial only is one of our main research questions," said Bos. ==

Rachel Feltman wrote in the Washington Post: “This coiffed corpse is just one of many that Bos is studying, all found in the cemetery of an ancient city we now call Amarna. She's looking at their hair to learn more about their city. Variation in hair type indicates that it was an ethnically diverse area, and the different styling techniques — which include many extensions, sometimes from multiple hair donors, even though all styles were kept around 12 inches long or less — will help her understand their culture.” ==

Changing Hairstyles for Men in Ancient Egypt

As seen in monuments and temple and tomb images short hair was originally the fashion for all classes in the Old Kingdom; for the shepherd and the boatman as well as for the prince, and was even worn by those in court dress. At the same time the great lords possessed also a more festive adornment for their heads in the shape of great artificial coiffures. Amongst them we must distinguish two kinds of wigs, the one made in imitation of short woolly hair, the other of long hair. The former consisted of a construction of little curls arranged in horizontal rows lapping over each other like the tiles of a roof; as a rule very little of the forehead was visible, and the ears were quite covered as well as the back of the neck. The details vary in many particulars, though this description is correct as a whole. The little curls are sometimes triangular, sometimes square; the hair is sometimes cut straight across the forehead, sometimes rounded; in many instances the little curls begin up on the crown of the head, in others high on the forehead; other differences also exist which can be also strikes us as humorous that the shepherds, or servants adorned with this once noble head-dress. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

On the other hand the second wig — that of long hair — seems never to have been displaced from its exclusive position, although it was certainly a more splendid head-dress than the stiff construction of little curls. In the long-haired wig the hair fell thickly from the crown of the head to the shoulders, at the same time forming a frame for the face; while round the forehead, and also at the ends, the hair was lightly waved. The individual tresses were sometimes twisted into spiral plaits.

Today we still marvel at the ancient Egyptian wig-maker's art. A certain Shepsesre', who held the office of superintendent of the south in the Old Kingdom at the court of King 'Ess'e, must have been specially anxious to excel in this respect. He caused four statues to be prepared for his tomb each representing him in a special coiffure. In two he wears the usual wigs, in the third his hair is long and flowing like that of a woman, and in the fourth he wears a wig of little curls, which reaches down to the middle of his back. The latter must have been an invention on the part of the wig-maker, for it would be impossible ever to dress a man's natural hair in such a wonderful manner. The same might be said of the wig which became the ruling fashion under the 6th dynasty. This consisted of a senseless combination of the two earlier forms; the long-haired coiffure, the whole style of which is only possible with long tresses, being divided, after the fashion of the other, into rows of little curls, though its waving lines were retained.

The upper classes were not the only ones who followed to the vagaries of fashion. In the earliest times the master alone and one or two of his household officials wore this wig. By by the time of the 5th dynasty we have many representations of workmen in similar wigs. Under the Middle Kingdom there was little change in the fashion of wearing the hair. The men of the upper classes still seem to have kept to the two ancient forms of wig, while the lower classes let the hair grow freely;' neither did the fashion change immediately on the expulsion of the Hyksos.

Only with the rise of Egyptian political power. From the second half of the 18th dynasty, fashions evidently rapidly succeeded each other, and wc arc not always able, from the material at our command to say exactly how long one single fashion lasted. We may distinguish two principal coiffures, a shorter one often covering the neck, and a longer one in which the thick masses of hair hung down in front over the shoulders. Both occur in numerous more or less anomalous varieties. A simple form of the shorter coiffure is shown in the accompanying representation of the head of Chaemhet, the superintendent of granaries; straight hair hangs down all round the head, being cut even at the back. As a rule however men were not content with anything so simple; fashion demanded curly hair, or at least a fringe of little curls framing the face, and a single tress hanging down loosely at the back. The second coiffure, which covers the shoulders, does not differ much in its simplest form from the shorter one; generally however it is a far more stately erection. ' The ends of the hair as well as the hair round the face are also sometimes curled in a charming though rather unnatural manner, as we see in representations of several great men of the 18th and 19th dynasties. The hair which falls over the shoulders is twisted into little separate curls forming a pretty contrast to the rest of the hair, which is generally straight. Both forms of coiffure which we have described were worn by all men of rank of the 18th and 19th dynasties; we see that they were really wigs, and not natural hair, by the change of coiffure worn by one and the same person. They lasted on into the 20th dynasty, at which time we also find long freely-waving hair.

Changing Hairstyles for Women in Ancient Egypt

Under the Old Kingdom the women of all classes wore a large coiffure of straight hair, hanging down to the breast in two tresses. Many pictures prove to us that these wonderful coiffures also were not always natural, for occasionally we find not only the servants without them, but also the grown-up daughters and the mistresses themselves," while the head appears to be covered with short hair. In a few instances we find a shorter form of coiffure worn occasionally by ladies of high birth. The hair does not hang longer than to the shoulders, and under the wig in front the natural hair can generally be seen covering the forehead almost to the eyes. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

During the long period of the Middle Kingdom, fashion, as regards ladies' hair, remained wonderfully stationary, the only innovation we can remark is, that the ends of the two tresses were formed into a pretty fringe. " With the great changes which Egyptian dress underwent towards the middle of the 18th dynasty several new fashions in ladies' as well as men's coiffures arose contemporarily, and apparently followed the same course. These seem to have been due to the desire for a freer and less stiff arrangement of the hair. The heavy tresses which formerly hung down in front are now abandoned; and the hair is made to cover either the whole of the upper part of the body or it is all combed back and hangs behind. The details vary very much. Sometimes the hair falls straight down, sometimes it is twisted together in plaits, at other times it is curled. Some women wear it long, others short and standing out; some frame the face with wonderful plaits,' and others with short tresses. '' Nearly all, however, twist the ends of several plaits or curls together, and thus make a sort of fringe to the heavy mass of hair.

A more graceful head-dress is that worn by the girl playing a musical instrument, in the London picture so often mentioned; curly hair lightly surrounds without concealing the shape of the head, whilst a few curls hang down behind like a pig-tail. In very similar fashion a young servant has arranged her plaits; three thick ones form the pig-tail, and eight smaller ones hang down over each cheek.

All these coiffures were worn by the ladies of the 18th dynasty; later, especially under the 20th dynasty, ladies came back to the old manner of dressing their hair, and again allowed a heavy tress to fall over each shoulder. They turned aside indeed very much from the old simplicity, they crimped their hair, and those who could afford it allowed their wigs to reach to below the waist. ' I say ivigs, for most of these coiffures must have been artificial, as we see by the fact that short coiffures were also worn on various occasions by the same ladies. ' To one of these ladies belonged the wig in the Berlin Museum, the long curls of which appear now very threadbare. It is not composed of human hair, but of sheep's wool; and these cheap preparations were doubtless usually worn. This custom of wearing artificial hair strikes us as very foolish, though perhaps not so much so as another custom with which it is closely allied.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024