ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN GOVERNMENT

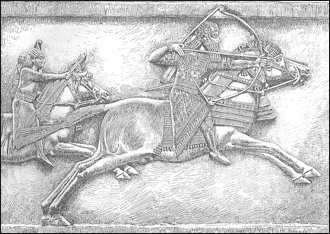

Bowing to the king in Assyria

The Mesopotamians arguably invented the centralized state and the developed kingship. Cities were political focal points as well as urban center and leadership was passed down by kingly dynasties. As Mesopotamian culture developed it city-states coalesced into kingdoms.

There were also many civil servants. One of the highest positions was the scribe, who worked closely with the king and the bureaucracy, recording events and tallying up commodities. Temples provided welfare service and protected widows and orphans. The earliest reforms protecting the poor, widows and orphans was found in Ur and date to around 2000 B.C.

Mesopotamians are said to have developed imperialism. The late second millennium B.C. has been called “the first international age.” It was a time when there was increased interaction between kingdoms. The Assyrians created a kingdom that embraced many smaller kingdoms made up a variety of different ethnic groups.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“At the Origins of Politics” by Giorgio Buccellati (2024) Amazon.com;

“Economic Complexity in the Ancient Near East: Management of Resources and Taxation (Third-Second Millenium BC)” by Jana Mynářová (Editor), Sergio Alivernini (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization” by Paul Kriwaczek (2010) Amazon.com;

“Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States” by James C. Scott (2018) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“For the Gods of Girsu: City-State Formation in Ancient Sumer” by Sébastien Rey (2016) Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

“Local Power in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia” by Andrea Seri (2011) Amazon.com;

“Writing, Law, and Kingship in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia” by Dominique Charpin, Jane Marie Todd (2010) Amazon.com;

“Temples of Enterprise: Creating Economic Order in the Bronze Age Near East”

by Michael Hudson (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Old Assyrian City-State and Its Colonies” by Mogens Trolle Larsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Ideology in Assyria” by Beate Pongratz-Leisten (2015) Amazon.com;

“Relations of Power in Early Neo-Assyrian State Ideology” by Mattias Karlsson (2016) Amazon.com;

“Royal Image and Political Thinking in the Letters of Assurbanipal (State Archives of Assyria Studies) by Sanae Ito (2024) Amazon.com;

“Grants, Decrees and Gifts of the Neo-Assyrian Period (State Archives of Assyria)

by L. Kataja and R. Whiting (1995) Amazon.com;

“Nippur IV: The Early Neo-Babylonian Governor's Archive from Nippur (Oriental Institute Publications) by Steven W. Cole (1996) Amazon.com;

“Legal and Administrative Texts from the Reign of Nabonidus” by Paul-Alain Beaulieu | (2000) Amazon.com;

Mesopotamian Theocratic Government

The conception of the state in Babylonia was intensely theocratic. The kings had been preceded by high-priests, and up to the last they performed priestly functions, and represented the religious as well as the civil power. At Babylon the real sovereign was Bel Marduk, the true “lord” of the city, and it was only when the King had been adopted by the god as his son that he possessed any right to rule. Before he had “taken the hands” of Bel, and thereby become the adopted son of the deity, he had no legitimate title to the throne. He was, in fact, the vicegerent and representative of Bel upon earth; it was Bel who gave him his authority and watched over him as a father over a son. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The Babylonian sovereign was thus quite as much a pontiff as he was a king. The fact was acknowledged in the titles he bore, as well as in the ceremony which legitimized his accession to the throne. But he continued to be supreme pontiff to the adopted son of the god of Babylon. Babylon had become the capital of the kingdom, and Marduk, its patron-deity, was, accordingly, supreme over the other gods of Chaldea. He alone could confer the royal powers that the god of every city which was the centre of a principality had once been qualified to grant. By “taking his hands” the King became his adopted son, and so received a legitimate right to the throne.

Sumer was a theocracy with slaves. Each city state worshiped its own god and was ruled by a leader who was said to have acted as an intermediary between the local god and the people in the city state. The leaders led the people into wars and controlled the complex water systems. Rich rulers built palaces and were buried with precious objects for a trip to the afterlife. A council of citizens may have selected the leaders.

Early Sumerians established a powerful priesthood that served local gods, who were worshiped in temples that dominated the early cities. Much of political and religious activity was oriented towards gods who controlled the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and nature in general. If people respected the gods and the gods acted benevolently the Sumerians thought the gods would provide ample sunshine and water and prevent hardships. If the people went against the wishes of the local god and the god was not so benevolent: droughts, floods, famine and locusts were the result. In Uruk kings took part n important religious rituals. One vase from Uruk shows a king presenting a whole set of gifts to a temple of the city goddess Inana. Kings supported temples and were expected to turn over some of the booty from wars and raids to temples.

Mesopotamian Leaders and City-State Governments

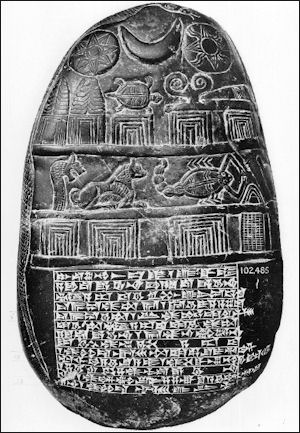

Kudurru of Gula-Eresh

Eblaite kings were responsible for looking after widows, orphans and the poor as well as hold together a strong and united kingdom. If they failed to look after the disadvantaged they were ousted by a group of elders. Citizens aired their grievances before the king in the audience court of the king's palace.

The early Mesopotamian city-states were ruled a council of elders that was led by a “ lugal” ("big man") who made decisions in times of crisis. Later on, when times of crisis were more prolong and continuous, the legal developed into a kings that like Egyptian rulers were elevated to god-like status and were said to have been "lowered from heaven.

In some Mesopotamia cities each quadrant was overseen by a “lugal” , a kind of ward boss. Rulers of relatively equal power often addressed one another as "brother." The more powerful often asked to be addressed by less powerful kings as "your father."

Some women did obtain positions of power. Cuneiform tablets at Cornell described a 21st century B.C. Sumerian princess in the city of Garsana that has made scholars rethink the role of women in the ancient kingdom of Ur. According to the Los Angeles Times: “ The administrative records show Simat-Ishtaran ruled the estate after her husband died. During her reign, women attained remarkably high status. They supervised men, received salaries equal to their male counterparts' and worked in construction, the clay tablets reveal. "It's our first real archival discovery of an institution run by a woman," said David Owen, the Cornell researcher who has led the study of the tablets. Because scholars do not know precisely where the tablets were found, however, the site of ancient Garsana cannot be excavated for further information.” [Source: Jason Felch, Los Angeles Times, November 3, 2013]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In the realm of politics, as early as 2700 B.C., statues of ancient Near Eastern Kings included inscriptions that cursed anyone who dared to desecrate their image. It was almost a rite of passage for conquering rulers or representatives of new dynasties to try to eliminate loyalty to their predecessors through the erasure of visual reminders of their reign. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 20, 2020]

Kings as Gods in Ancient Mesopotamia

Two views prevailed, however, as to his relation to the god. According to one of these, sonship conferred upon him actual divinity; he was not merely the representative of a god, but a god himself. This was the view which prevailed in the earlier days of Semitic supremacy. Sargon of Akkad and his son Naram-Sin are entitled “gods;” temples and priests were dedicated to them during their lifetime, and festivals were observed in their honor. Their successors claimed and received the same attributes of divinity. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Under the third dynasty of Ur even the local prince, Gudea, the high-priest of Tello, was similarly deified. It was not until Babylonia had been conquered by the foreign Kassite dynasty from the mountains of Elam that a new conception of the King was introduced. He ceased to be a god himself, and became, instead, the delegate and representative of the god of whom he was the adopted son. His relation to the god was that of a son during the lifetime of his father, who can act for his father, but cannot actually take the father's place so long as the latter is alive. Some of the earlier Chaldean monarchs call themselves sons of the goddesses who were worshipped in the cities over which they held sway. They thus claimed to be of divine descent, not by adoption, but by actual birth. The divinity that was in them was inherited; it was not merely communicated by a later and artificial process. The “divine right,” by grace of which they ruled, was the right of divine birth. At the outset, therefore, the Babylonian King was a pontiff because he was also a god. In him the deities of heaven were incarnated on earth. He shared their essence and their secrets; he knew how their favor could be gained or their enmity averted, and so mediated between god and man.

This deification of the King, however, cannot be traced beyond the period when Semitic rule was firmly established in Chaldea. It is true that Sumerian princes, like Gudea of Lagas, were also deified; but this was long after the rise of Semitic supremacy, and the age of Sargon of Akkad, and when Sumerian culture was deeply interpenetrated by Semitic ideas. So far as we know at present the apotheosis of the King was of Semitic origin. It is paralleled by the apotheosis of the King in ancient Egypt. There, too, the Pharaoh was regarded as an incarnation of divinity, to whom shrines were erected, priests ordained, and sacrifices offered.

Naram-Sin was a ruler of the Akkadian Empire, reigning from c. 2254–2218 B.C. He is addressed as “the god of Agadê,” or Akkad, the capital of his dynasty, and long lists have been found of the offerings that were made, month by month, to the deified Dungi, King of Ur, and his vassal, Gudea of Lagas. One of these goes: “I. Half a measure of good beer and 5 gin of sesame oil on the new moon, the 15th day, for the god Dungi; half a measure of good beer and half a measure of herbs for Gudea the High-priest, during the month Tammuz. II. Half a measure of the king's good beer, half a measure of herbs, on the new moon, the 15th day, for Gudea the Highpriest. One measure of good wort beer, 5 qas of ground flour, 3 qas of cones (?), for the planet Mercury: during the month of the festival of the god Dungi. III.… Half a measure of good beer, half a measure of herbs, on the new moon, the 15th day, for the god Gudea the High-priest: during the month Elul, the first year of Gimil-Sin, king [of Ur].”

Political Power in Mesopotamia

Assurbanipal chase Morris Jastrow said: In Babylonia and Assyria “the people, as a whole, had no share in the government, and, as we have seen, only a limited share in the religious cult, which was largely official and centered around the general welfare and the well-being of the king and his court. Slavery continued in force to the latest days, and, though slaves could buy their freedom and could be adopted by their masters, and had many privileges, even to the extent of owning property and engaging in commercial transactions, yet the moral effect of the institution in degrading the dignity of human life, and in maintaining unjust class distinctions was none the less apparent then than it has been ever since. The temples had large holdings which gave to the religious organisation of the country a materialistic aspect, and granted the priests an undue influence. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Political power and official prestige were permanently vested in the rulers and their families and attendants. We hear, occasionally, of persons of humble birth rising to high positions, but the division of the classes into higher and those of lower ranks was on the whole rigid. Uprisings were not infrequent both in Babylonia and Assyria, and internal dissensions, followed by serious disturbances, revealed the dissatisfaction of the majority with the yoke imposed upon them, which, especially through enforced military service and through taxes for the maintenance of temples, armies, and the royal court, must often have borne heavily on them. The cruelties, practised especially by the Assyrian rulers in times of war, must also have reacted unfavourably on the general moral tone of the population. Assyria was cruel toward her foes and, if Babylonia has a gentler record, it is because she never so greatly developed military prowess as did her northern cousin.

In both Babylonia and Assyria there was an aristocracy of birth based originally on the possession of land. But in Babylonia it tended at an early period to be absorbed by the mercantile and priestly classes, and in later days it is difficult to find traces even of its existence. The nobles of the age of Nebuchadnezzar were either wealthy trading families or officers of the Crown. The temples, and the priests who lived upon their revenues, had swallowed up a considerable part of the landed and other property of the country, which had thus become what in modern Turkey would be called wakf. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

In Assyria many of the great princes of the realm still belonged to the old feudal aristocracy, but here again the tendency was to replace them by a bureaucracy which owed its position and authority to the direct favor of the King. Under Tiglath-pileser III. this tendency became part of the policy of the government; the older aristocracy disappeared, and instead of it we find military officers and civil officials, all of whom were appointed by the Crown.

Ethics of Rulers and Leadership in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “The kings themselves, although not actuated, perhaps, by the highest motives, set the example of obedience to laws that involved the recognition of the rights of others. From a most ancient period there is come down to us a remarkable monument recording the conveyance of large tracts of land in northern Babylonia to a king of Kish, Manishtusu, (ca . 2700 B.C.), on which hundreds of names are recorded from whom the land was purchased, with specific descriptions of the tracts belonging to each one, as well as the conditions of sale. The king here appears with rights no more exclusive or predominant than those of a private citizen. Not only does he give full compensation to each owner, but undertakes to find occupation and means of support for fifteen hundred and sixty-four labourers and eighty-seven overseers, who had been affected by the transfer. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The numerous boundary stones that are come down to us (recording sales of fields or granting privileges), which were set up as memorials of transactions, are silent but eloquent witnesses to the respect for private property. The inscriptions on these stones conclude with dire curses in the names of the gods against those who should set up false claims, or who should alter the wording of the agreement, or in any way interfere with the terms thereon recorded. The symbols of the gods were engraved on these boundary stones as a precaution and a protection to those whose rights and privileges the stone recorded. The Babylonians could well re-echo the denunciations of the Hebrew prophets against those who removed the boundaries of their neighbours’ fields. Even those Assyrian monarchs most given to conquest and plunder boast, in their annals, of having restored property to the rightful owners, and of having respected the privileges of their subjects and dependents.

“For instance, Sargon of Assyria (721-705 B.C.), while parading his conquests in vain-glorious terms, and proclaiming his unrivalled prowess, emphasises the fact that he maintained the privileges of the great centres of the south, Sippar, Nippur, and Babylon, and that he protected the weak and righted their injuries. His successor Sennacherib claims to be the guardian of justice and a lover of righteousness. Yet, these are the very same monarchs who treated their enemies with unspeakable cruelty, inflicting tortures on prisoners, violating women, mutilating corpses, burning and pillaging towns.

Cylinder Nabonidus“More significant still is the attitude of a monarch like Hammurabi, who, in the prologue and epilogue to his famous Code, refers to himself as a “king of righteousness,” actuated by a lofty desire to protect the weak, the widow, and the orphan. In setting up copies of this Code in the important centres of his realm, his hope is that all may realise that he, Hammurabi , tried to be a “father” to his people. He calls upon all who have a just cause to bring it before the courts, and gives them the assurance that justice will be dispensed,—all this as early as nigh four thousand years ago!

“On a tablet commemorative of the privileges accorded to Sippar, Nippur, and Babylon—to which, we have just seen, Sargon refers in his annals—there are grouped together, in the introduction, a series of warnings, which may be taken as general illustrations of the principles by which rulers were supposed to be guided:

If the king does not heed the law, his people will be destroyed; his power will pass away.

If he does not heed the law of his land, Ea, the king of destinies, will judge his fate and cast him to one side.

If he does not heed his abkallu, his days will be shortened.

If he does not heed the priestess, his land will rebel against him.

If he gives heed to the wicked, confusion will set in.

If he gives heed to the counsels of Ea, the great gods will aid him in righteous decrees and decisions.

If he oppresses a man of Sippar and perverts justice, Shamash, the judge of heaven and earth, will annul the law in his land, so that there will be neither abkallu nor judge to render justice.

If the Nippurians are brought before him for judgment, and he oppresses them with a heavy hand, Enlil, the lord of lands, will cause him to be dispatched by a foe and his army to be overthrown; chief and general will be humiliated and driven off.

If he causes the treasury of the Babylonians to be entered for looting, if he annuls and reverses the suits of the Babylonians, then Marduk, the lord of heaven and earth, will bring his enemy against him, and will turn over to his enemy his property and possessions.

If he unjustly orders a man of Nippur, Sippar, or Babylon to be cast into prison, the city where the injustice has been done, will be made desolate, and a strong enemy will invade the prison into which he has been cast.

“In this strain the text proceeds; and while the reference is limited to the three cities, the obligations imposed upon the rulers to respect privileges once granted may be taken as a general indication of the standards everywhere prevailing. We must not fail, however, to recognise the limitation of the ethical spirit, manifest in the threatened punishments, should the ruler fail to act according to the dictates of justice and right. For all this, whether it was from fear of punishment, or desire to secure the favour of the gods, the example of their rulers in following the paths of equity and in avoiding tyranny and oppression must have reacted on their subjects, and incited them to conform their lives to equally high standards.”

Assyrian Rule

In Assyria, in contrast to Babylonia, the government rested on a military basis. It is true that the kings of Assyria had once been the high-priests of the city of Assur, and that they carried with them some part of their priestly functions when they were invested with royal power. But it is no less true that they were never looked upon as incarnations of the deity or even as his representative upon earth. The rise of the Assyrian kingdom seems to have been due to a military revolt; at any rate, its history is that of a succession of rebellious generals, some of whom succeeded in founding dynasties, while others failed to hand down their power to their posterity. There was no religious ceremony at their coronation like that of “taking the hands of Bel.” [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

When Esar-haddon was made King he was simply acclaimed sovereign by the army. It was the army and not the priesthood to whom he owed his title to reign. The conception of the supreme god himself differed in Assyria and Babylonia. In Babylonia, Bel-Marduk was “lord” of the city; in Assyria, Assur was the deified city itself. In the one case, therefore, the King was appointed vicegerent of the god over the city which he governed and preserved; in the other case the god represented the state, and, in so far as the King was a servant of the god, he was a servant also of the state.

See Separate Article: ASSYRIAN LAWS AND GOVERNMENT africame.factsanddetails.com

Legacy of Babylonian Rule

Even after the Babylonian rulers lost power it was not forgotten that Babylonia had once been the mistress of Western Asia, and it was, accordingly, the sceptre of Western Asia that was conferred by Bel Marduk upon his adopted sons. Like the Holy Roman Empire in the Middle Ages, Babylonian sovereignty brought with it a legal, though shadowy, right to rule over the civilized kingdoms of the world. It was this which made the Assyrian conquerors of the second Assyrian empire so anxious to secure possession of Babylon and there “take the hands of Bel.” [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Tiglath-pileser III., Shalmaneser IV., and Sargon were all alike usurpers, who governed by right of the sword. It was only when they had made themselves masters of Babylon and been recognized by Bel and his priesthood that their title to govern became legitimate and unchallenged. Cyrus and Cambyses continued the tradition of the native kings. They, too, claimed to be the successors of those who had ruled over Western Asia, and Bel, of his own free choice, it was alleged, had rejected the unworthy Nabonidos and put Cyrus in his place.

Cyrus ruled, not by right of conquest, but because he had been called to the crown by the god of Babylon. It was not until the Zoroastrean Darius and Xerxes had taken Babylon by storm and destroyed the temple of Bel that the old tradition was finally thrust aside. The new rulers of Persia had no belief in the god of Babylon; his priesthood was hostile to them, and Babylon was deposed from the position it had so long occupied as the capital of the world.

Bureaucracy and Censuses in Ancient Mesopotamia

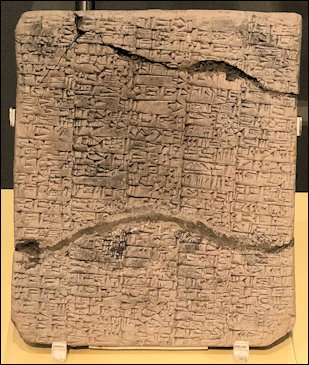

Babylonian tablet with administrative text

The Mesopotamians are also credited with inventing government bureaucracy. The day-to-day affairs of government were handled by scribes and palace officials. They made records of the tithes and transactions of farmers. Private ownership is the key-note of Babylonian social life. But the whole of this social life was fenced about by a written law. No title was valid for which a written document could not be produced, drawn up and attested in legal forms. The extensive commercial transactions of the Babylonians made this necessary, and the commercial spirit dominated Babylonian society. The scribe and the lawyer were needed at almost every juncture of life. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Like present-day governments, governments in the ancient world, whether Mesopotamia or Canaan, placed a great deal of emphasis on the need for statistical, especially demographic, information. One of the best ways of obtaining such information was by means of a census. Scholars have been bothered by certain aspects of the census as noted in the Bible (Ex. 30:11–16; Num. 1:1 19), and questioned the need on the part of the participants in the census for ritual expiation. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Documents discovered in the royal archives of Mari in northern Mesopotamia have greatly helped to clarify the problem. In one letter discovered in the archives the following order is given: "Let the troops be recorded by name" (G. Dossin, Archives royales de Mari, 1 (1950), no. 42, lines 22–24; cf. Num. 1:2). In other words, a list of names was to be prepared. Such lists are also available from many other sites in the Ancient Near East. The technical term for a census at Mari was tēbibtum, "purification" (according to other scholars, "expert counting"). [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

At Mari as in the Bible there appears to be a connection between census and purification. It is known that in Mesopotamia there existed a definite fear among the people of having their names put on lists. The similarity between the census and the books of life and death caused a feeling of discomfort about a census. There is much in common between the institution of the census in Mari and in Israel. The purposes of the censuses were similar: they served as military lists and for the division of property. So too, some of the technical terms associated with the census are similar: Hebrew pqd and Akkadian paqādum, "to count"; Hebrew kippurim and Akkadian ubbubum "purification." Censuses in Israel, as in Mari, were taken by writing down the names, as noted in Numbers 1:2: be-mispar shemot, "according to the number of the names." It is likely then that the reason for the expiation connected with the census in Israel was the same as in Mari. There is a reference to a book of life in the Bible (Ex. 32:32–33), when Moses, pleading for Israel after they sinned with the golden calf, says "Erase me from the book that You have written." The concept of a book of life and death is well known among Jews in the mishnaic period. Its antecedents go back to the biblical period.

Scribes in the Mesopotamian Bureaucracy

One of the highest positions in Mesopotamia society was the scribe, who worked closely with the king and the bureaucracy, recording events and tallying up commodities. The kings were usually illiterate and they were dependent on the scribes to make their wishes known to their subjects. Learning and education was primarily the provenance of scribes.

In ancient Mesopotamia writing — and also reading — was a professional rather than a general skill. Being a scribe was an honorable profession. Professional scribes prepared a wide range of documents, oversaw administrative matters and performed other essential duties.Some scribes could write very fast. One Sumerian proverb went: "A scribe whose hands move as fast the mouth, that's a scribe for you." Scribes were the only formally educated members of society. They were trained in the arts, mathematics, accounting and science. They were employed mainly at palaces and temples where their duties included writing letters, recording sales of land and slaves, drawing up contracts, making inventories and conducting surveys. Some scribes were women.

In ancient Mesopotamia scribes constituted a special class and occupied an important position in the bureaucracy. They acted as clerks and secretaries in the various departments of state, and stereotyped a particular form of cuneiform script, which we may call the chancellor's hand, and which, through their influence, was used throughout the country. In Babylonia it was otherwise. Here a knowledge of writing was far more widely spread, and one of the results was that varieties of handwriting became as numerous as they are in the modern world. The absence of a professional class of scribes prevented any one official hand from becoming universal. We find even the son of an “irrigator,” one of the poorest and lowest members of the community, copying a portion of the “Epic of the Creation,” and depositing it in the library of Borsippa for the good of his soul. Indeed, the contract tablets show that the slaves themselves could often read and write. The literary tendencies of Assur-bani-pal doubtless did much toward the spread of education in Assyria, but the latter years of his life were troubled by disastrous wars, and the Assyrian empire and kingdom came to an end soon after his death. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The scribes were a large and powerful body, and in Assyria, where education was less widely diffused than in Babylonia, they formed a considerable part of the governing bureaucracy. In Babylonia they acted as librarians, authors, and publishers, multiplying copies of older books and adding to them new works of their own. They served also as clerks and secretaries; they drew up documents of state as well as legal contracts and deeds. They were accordingly responsible for the forms of legal procedure, and so to some extent occupied the place of the barristers and attorneys of to-day. The Babylonian seems usually, if not always, to have pleaded his own case; but his statement of it was thrown into shape by the scribe or clerk like the final decision of the judges themselves.

Under Nebuchadnezzar and his successors such clerks were called “the scribes of the king,” and were probably paid out of the public revenues. Thus in the second year of Evil-Marduk it is said of the claimants to an inheritance that “they shall speak to the scribes of the king and seal the deed,” and the seller of some land has to take the deed of quittance “to the scribes of the king,” who “shall supervise and seal it in the city.” Many of the scribes were priests; and it is not uncommon to find the clerk who draws up a contract and appears as a witness to be described as “the priest” of some deity.

See Separate Article: CUNEIFORM (MESOPOTAMIAN WRITING): DEVELOPMENT, SCRIBES, PRODUCTION, SUBJECTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Welfare and Socialism in Ancient Mesopotamia

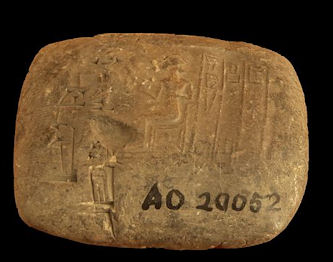

daily salary in Ur Some scholars have described the Mesopotamian system of government as a "theocratic socialism." The center of the government was the temple, where projects like the building of dikes and irrigation canals were overseen, and food was divided up after the harvest. Most Sumerian writing recorded administrative information and kept accounts. Only priests were allowed to write.

Some have called Sumer the epitome of the welfare city-state. Sam Roberts in the New York Times, “Work was a duty, but social security was an entitlement. It was personified by the Goddess Nanshe, the first real welfare queen immortalized in hymn as a benefactor who “brings the refugee to her lap, finds shelter for the weak.”... Nanshe, the Mesopotamian goddess, was hailed by some bards of Sumer for her compassion and, undoubtedly, denounced by others as a dupe." [Source: Sam Roberts, New York Times, July 5, 1992]

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: One of the most vivid glimpses into the mind of an ancient ruler was unearthed in 1928, at the royal cemetery of Ur, in modern-day Iraq. The so-called Standard of Ur, dating to around 2500 B.C., is a foot-and-a-half-long trapezoidal wooden box decorated with mosaics made of lapis lazuli, shell, and red limestone that depict a flourishing Mesopotamian city-state. On one side of the box, average citizens dutifully line up to offer produce, sheep, and other livestock as taxes to the king, who is shown with his retinue feasting on the revenues. On the opposite side, the king’s army, funded by tax levies, is seen smiting Ur’s enemies. Both scenes illustrate a king’s-eye view of a highly idealized government functioning with great efficiency thanks to what has become a universal human experience. [Source: Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: [Source: Eric A. Powell Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2021]

Taxes in Ancient Mesopotamia

Many taxes were in the form of tithes paid by farmers.Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica: “The state claimed certain proportions of all crops, stock, etc. The king's messengers could commandeer any subject's property, giving a receipt. Further, every city had its own octroi duties, customs, ferry dues, highway and water rates. The king had long ceased to be, if he ever was, owner of the land. He had his own royal estates, his private property and dues from all his subjects. The higher officials had endowments and official residences.[Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911]

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: A vast body of eclectic evidence reveals how rulers administered taxes on everything from crops to labor, how people complied with their mandate, and how taxes could contribute to the well-being of the state. But these artifacts also show that while the powerful had ambitious plans to extract revenue, at least in some cases, taxpayers themselves did not behave with the perfect compliance of the subjects depicted on the Standard of Ur. “Everybody gets taxed,” says University of Michigan historian Irene Soto Marín, who studies taxation in Roman-era Egypt. She points out that the archaeological record is replete with documents recording the typical person’s tax burden. “Many of the texts that survive from the ancient world aren’t literary works, but mundane tax receipts,” Soto Marín says. “They’re the most direct way to get insight into the policies of ancient states and the impact those policies had on people’s daily lives.” [Source: Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: [Source: Eric A. Powell Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2021]

Around 2112 B.C., the Sumerian king Ur-Namma (r. 2112–2095 B.C.) united the city-states of southern Mesopotamia into a short-lived kingdom known today as the Third Dynasty of Ur, or Ur III. More than 100,000 clay cuneiform tablets, many recording taxes paid to the royal household, date to this era. “It’s one of the most documented periods in the ancient world,” says Western Washington University Assyriologist Steven Garfinkle. “In some cases we can track a single sheep through the tax system across multiple tablets, all the way to the king’s kitchens.” The taxes the Ur III kings levied relied on the bala system, a local tax that was probably already more than 1,000 years old by that point. The rulers also collected direct payments from a new class of nobles empowered by the rise of the Ur III state — who may have even welcomed paying taxes. “These new local elites relied on the royal recognition of their property rights,” says Garfinkle, “and paying taxes to the king was one way to ensure the legitimacy of their new status.”

These newly powerful figures were able to pay their taxes by joining the king on annual raids against people living on the periphery of the Ur III state, especially to the east in present-day Iran. There they captured great quantities of sheep, slaves, and other plunder, part of which they then turned over to the king, who relied heavily on these payments. “We’re tempted to think of Ur III as this powerful centralized state,” says Garfinkle. “But close study of the tablets and the tax system shows that it was actually quite fragile and dependent on nearly constant warfare.”

A century after the kingdom’s founding, the power of the kings of Ur waned and they were no longer able to lead the raiding campaigns that had been so critical to their survival. Around 2004 B.C., the rulers of Elam, a land to the east of Mesopotamia that was one of the most frequent targets of the Ur III raids, turned the tables and deposed the last Ur III king, Ibbi-Sin, who was taken away to Elam in chains.

People in Babylonian and Assyrian Colonies and Conquered Lands

Among Assyrian and Babylonian officials we meet with many who bear foreign names, and among the gods whose statues found a place in the national temples of Assyria were Khaldis of Armenia, and the divinities of the Bedouin. The policy of deporting a conquered nation was dictated by the same readiness to admit the stranger to the rights and privileges of a homeborn native. The restrictions placed upon Babylonian and Assyrian citizenship seem to have been but slight. When Abraham was born at Ur of the Chaldees, Babylonia was governed by a dynasty of South Arabian origin whose names had to be translated into the Babylonian language. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Throughout the country there were colonies of “Amorites,” from Syria and Canaan, doubtless established there for the purposes of trade, who enjoyed the same rights as the native Babylonians. They could hold and bequeath land and other property, could buy and sell freely, could act as witnesses in a case where natives alone were concerned, and could claim the full protection of Babylonian law. The Amorites of Canaan may have been allowed to settle wherever they liked, and the origin of the title “district of the Amorites” may have simply been due to the tendency of foreign settlers to establish themselves in the same locality.

Amorites could rise to the highest offices of state. Not only could they serve as witnesses to a deed, to which all the other parties were native Babylonians, they could also hold civil and military appointments. On the one hand we find the son of Abi-ramu, or Abram, who is described as “the father of the Amorite,” acting as a witness to a contract dated in the reign of the grandfather of Hammurabi, or Amraphel; on the other hand, “an Amorite” has the same title of “servant” of the King as the royal judge Ibku-Anunit, and among the Assyrians of the second empire, who were slavish imitators of Babylonian custom and law, we meet with more than one example of a foreigner in the service of the Assyrian government.

Rights of Foreigners in Ancient Mesopotamian Colonies

One of these colonies, known as “the district of the Amorites,” was just outside the walls of Sippara. In the reign of Ammi-zadok, the fourth successor of Hammurabi, a dispute arose about the title to some land included within it, and the matter was tried before the four royal judges. The following record of the judgment was drawn up by the clerk of the court: “Twenty acres by thirteen of land in the district of the Amorites which was purchased by Ibni-Hadad, the merchant. Arad-Sin, the son of Edirum, has pleaded as follows before the judges: The building land, along with the house of my father, he did not buy; Ibku-Anunit and Dhab-Istar, the sons of Samas-nazir, sold (it) for money to Ibni-Hadad, the merchant. Iddatum and Mazitum, the sons of Ibni-Hadad the merchant, appeared before the judges; they lifted up (their hands) and swore that it had been put up for sale; it had been bought by Edirum and Sin-nadni-sû who handed it over to Samas-nazir and Ibku-Anunit, selling it to them for money. The estate, consisting of twenty-two acres of land enclosed by thirty other acres, as well as eleven trees [and] a house, in the district of the Amorites, bounded at the upper end by the estate of — — , and at the lower end by the river Bukai (?), is contracted in width, and is of the aforesaid nature.

Judgment has been given for Arad- Sin, the son of Edirum, as follows: At the entrance to Sippara the property is situated (?), and after being put up for sale was bought by Samas-nazir and Ibku-Anunit, to whom it was handed over; power of redemption is allowed (?) to Arad-Sin; the estate is there, let him take it. Before Urukimansum the judge, Sin-ismeani the judge, Ibku-Anunit the judge, and Ibku-ilisu the judge. The 6th day of the month Tammuz, the year when Ammi-zadok the king constructed the very great aqueduct (?) for the mountain and its fountain (?) for the house of Life.” If we may argue from the names, Arad-Sin, who brought the action, was of Babylonian descent; and in this case native Babylonians as well as foreigners could hold land in the district in which the Amorites had settled. The fact that Arad-Sin seems to have been a Babylonian, and that his action was brought before Babylonian judges, is in favor of the view that such was the case. Moreover, as Mr. Pinches has pointed out,

At any rate, in the eyes of the law, the native and the foreign settler must have been upon an equal footing; they were tried before the same judges, and the law which applied to the one applied equally to the other. It is clear, moreover, that the foreigner had as much right as the native to buy, sell, or bequeath the soil of Babylonia. Whether or not this right was restricted to particular districts, we do not know. In Syria, in later days, “streets,” or rows of shops in a city, could be assigned to the members of another nationality by special treaty, as we learn from I Kings xx. 34, and at the end of the Egyptian eighteenth dynasty we hear of a quarter at Memphis being given to a colony of Hittite merchants, but such special assignments of land may not have been the custom in ancient Chaldea.

The following lawsuit which came before the courts in the reign of Hammurabi shows that there were special judges for cases in which Amorites were concerned and that they sat at “the gate of Nin-Marki.” “Concerning the garden of Sin-magir which Nahid-Amurri bought for money. Ilu-bani claimed it for the royal stables, and accordingly they went to the judges, and the judges sent them to the gate of Nin-Marki and the judges of the gate of Nin-Marki. In the gate of Nin-Marki Ilu-bani pleaded as follows: I am the son of Sin-magir; he adopted me as his son, and the seal of the document has never been broken. He further pleaded that ever since the reign of the deified Rim-Sin (Arioch) the garden and house had been adjudged to Ilu-bani. Then came Sin-mubalidh and claimed the garden of Ilu-bani, and they went to the judges and the judges pronounced that ‘to us and the elders they have been sent and in the gate of the gods Marduk, Sussa, Nannar, Khusa, and Nin-Marki, the daughter of Marduk, in the judgment-hall, the disputants (?) have stood, and the elders before whom Nahid-Amurri first appeared in the gate of Nin-Marki have heard the declaration of Ilu-bani.’

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024