ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN ECONOMICS

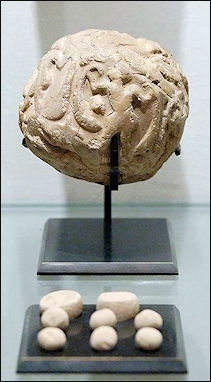

Accounting clay envelope Mesopotamia was the first place where crop surpluses were produced to such a degree that enough labor was freed that it could be harnessed to build cities and monuments, produce art and crafts and support merchants, temples and monarchs.

The Sumerian used the world’s first writing to record economic transactions and participate in a trade network that extended over thousands of miles. The Babylonians are credited with expanding commerce and developing an early banking system.

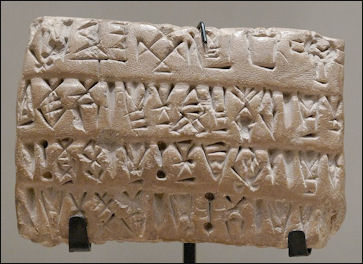

Most of the early writing was used to make lists of commodities. The writing system is believed to have developed in response to an increasingly complex society in which records needed to be kept on taxes, rations, agricultural products and tributes to keep society running smoothly.

The oldest examples of Sumerian writing were bills of sales that recorded transactions between a buyer and seller. When a trader sold ten head of cattle he included a clay tablet that had a symbol for the number ten and a pictograph symbol of cattle.

The Mesopotamians could also be described as the worlds first great accountants. They recorded everything that was consumed in the temples on clay tablets and placed them in the temple archives. Many of the tablets recovered were lists of items like this. Royal seals were affixed to products.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History” by Nicholas Postgate (1994) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society of Ancient” Mesopotamia (Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Records) by Steven Garfinkle and Gonzalo Rubio (2025) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society in Northern Babylonia (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta)

by A Goddeeris (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Economy” by M. I. Finley (1912-1986) and Ian Morris (1999) Amazon.com;

“Economic Complexity in the Ancient Near East: Management of Resources and Taxation (Third-Second Millenium BC)” by Jana Mynářová (Editor), Sergio Alivernini (Editor) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Woe; a Study of the Origin of Certain Banking Practices and of Their Effect on the Events of Ancient History Written in the Light of the Present Day” by David Astle | (1975) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy”

by Mario Liverani (2014) Amazon.com;

“Ledgers and Prices: Early Mesopotamian Merchant Accounts” by Daniel C. Snell (1982) Amazon.com;

“Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East” by Hans J. Nissen, Peter Damerow, Robert K. Englund (Author), Amazon.com;

“Selected Business Documents On the Neo-Babylonian Period” by Ungnad Arthur (2022) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Rental Houses in the Neo-Babylonian Period (VI-V Centuries BC)” by Stefan Zawadzki (2018) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

Industry, Resources and Business in Mesopotamia

Economic tablet from Susa Organized production of handcrafted goods was first developed in Mesopotamia. The Sumerians produced manufactured goods. The weaving of wool by thousands of workers is regarded as the for large-scale industry.

The Sumerians a developed sense of ownership and private property. It seems like many business transactions were recorded and the minutest amounts and smallest quantities were listed. Contracts were sealed with cylinder seals that were rolled over clay to produce a relief image.

There wasn't much in Ur and other cities in Mesopotamia except water from the Euphrates River and mud brick made from the dry earth. Prized materials such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, agate, carnelian all were imported.

See Naptu, Oil

See Separate Article: BUSINESS IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Herodotus on Babylonian Economic Activity

Herodotus wrote in 430 B.C.:“Among many proofs which I shall bring forward of the power and resources of the Babylonians, the following is of special account. The whole country under the dominion of the Persians, besides paying a fixed tribute, is parceled out into divisions, which have to supply food to the Great King and his army during different portions of the year. Now out of the twelve months which go to a year, the district of Babylon furnishes food during four, the other of Asia during eight; by the which it appears that Assyria, in respect of resources, is one-third of the whole of Asia. Of all the Persian governments, or satrapies as they are called by the natives, this is by far the best. When Tritantaechmes, son of Artabazus, held it of the king, it brought him in an artaba of silver every day. The artaba is a Persian measure, and holds three choenixes more than the medimnus of the Athenians. He also had, belonging to his own private stud, besides war horses, eight hundred stallions and sixteen thousand mares, twenty to each stallion. Besides which he kept so great a number of Indian hounds, that four large villages of the plain were exempted from all other charges on condition of finding them in food. I.193: But little rain falls in Assyria, enough, however, to make the corn begin to sprout, after which the plant is nourished and the ears formed by means of irrigation from the river. For the river does not, as in Egypt, overflow the corn-lands of its own accord, but is spread over them by the hand, or by the help of engines. [Source: Herodotus, “The History”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

“The whole of Babylonia is, like Egypt, intersected with canals. The largest of them all, which runs towards the winter sun, and is impassable except in boats, is carried from the Euphrates into another stream, called the Tigris, the river upon which the town of Nineveh formerly stood. Of all the countries that we know there is none which is so fruitful in grain. It makes no pretension indeed of growing the fig, the olive, the vine, or any other tree of the kind; but in grain it is so fruitful as to yield commonly two-hundred-fold, and when the production is the greatest, even three-hundred-fold. The blade of the wheat-plant and barley-plant is often four fingers in breadth. As for the millet and the sesame, I shall not say to what height they grow, though within my own knowledge; for I am not ignorant that what I have already written concerning the fruitfulness of Babylonia must seem incredible to those who have never visited the country. The only oil they use is made from the sesame-plant. Palm-trees grow in great numbers over the whole of the flat country, mostly of the kind which bears fruit, and this fruit supplies them with bread, wine, and honey. They are cultivated like the fig-tree in all respects, among others in this. The natives tie the fruit of the male-palms, as they are called by the Hellenes, to the branches of the date-bearing palm, to let the gall-fly enter the dates and ripen them, and to prevent the fruit from falling off. The male-palms, like the wild fig-trees, have usually the gall-fly in their fruit. I.194:

Babylon

“But that which surprises me most in the land, after the city itself, I will now proceed to mention. The boats which come down the river to Babylon are circular, and made of skins. The frames, which are of willow, are cut in the country of the Armenians above Assyria, and on these, which serve for hulls, a covering of skins is stretched outside, and thus the boats are made, without either stem or stern, quite round like a shield. They are then entirely filled with straw, and their cargo is put on board, after which they are suffered to float down the stream. Their chief freight is wine, stored in casks made of the wood of the palm-tree. They are managed by two men who stand upright in them, each plying an oar, one pulling and the other pushing. The boats are of various sizes, some larger, some smaller; the biggest reach as high as five thousand talents' burthen. Each vessel has a live ass on board; those of larger size have more than one. When they reach Babylon, the cargo is landed and offered for sale; after which the men break up their boats, sell the straw and the frames, and loading their asses with the skins, set off on their way back to Armenia. The current is too strong to allow a boat to return upstream, for which reason they make their boats of skins rather than wood. On their return to Armenia they build fresh boats for the next voyage. I.195:

Money in Mesopotamia

Among the Sumerians economic units of measure were the 1) gur, a unit of volume roughly equal to 26 bushels; 2) kug or ku, silver or money; and 3) gin or gig, a small axe head used as money roughly equal to a shekel. John Alan Halloran wrote in sumerian.org: “From the Ur III period we have tablets from different places and times that give the silver equivalents of different quantities of different commodities.During the Ur III period, the state was the main creditor. The state supplied so much land or so many animals to the individual, who then had to pay the state back. [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

Silver rings were used in Mesopotamia and Egypt as currency about 2000 years before the first coins were struck. Some archaeologists suggest that money was used by wealthy citizens of Mesopotamia as early as 2,500 B.C., or perhaps a few hundred years earlier. Historian Marvin Powell of Northern Illinois in De Kalb told Discover, "Silver in Mesopotamia functions like our money today. It’s a means of exchange. People use it for storage of wealth, and the use it for defining value."[Source: Heather Pringle, Discover, October 1998]

According to the Austrian Archaeological Institute, the earliest known coins were produced in about the seventh century B.C. in the kingdom of Lydia, in present-day Turkey, and in the ancient Greek cities of the nearby Ionian coast. The first coins were made of electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. Pure silver became standard in later centuries. The difference between the silver rings used in Mesopotamia and earliest coins first produced in Lydia in the 7th century B.C. was that the Lydian coins had the stamp of the Lydian king and thus were guaranteed by an authoritative source to have a fixed value. Without the stamp of the king, people were reluctant to take the money at face value from a stranger.

Archaeologists have had a difficult time sorting out information on ancient money because, unlike pottery or utensils, found in abundant supply at archeological sites, they didn't thrown them out.

See Separate Article: MONEY IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Modern Banking Began in Ancient Babylonian Temples

In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia gold, silver and other valuables were deposited in temples for safe-keeping. The history of banks can be traced to ancient Babylonian temples in the early 2nd millennium B.C.. In Babylon at the time of Hammurabi, there are records of loans made by the priests of the temple. Temples took in donations and tax revenue and amassed great wealth. Then, they redistributed these goods to people in need such as widows, orphans, and the poor. [Source: MessageTo Eagle March 7, 2016 Ancient History Facts]

After a thousand years, the priests who ran the temples had so much money that the concept of banking came up as an idea. Around the time of Hammurabi, in the 18th century B.C., the priests allowed people to take loans. Old Babylonian temples made numerous loans to poor and entrepreneurs in need. Among many other things, the Code of Hammurabi recorded interest-bearing loans.”

The text on a cuneiform tablet detailing a loan of silver, c. 1800 B.C., reads: “3 1/3 silver sigloi, at interest of 1/6 sigloi and 6 grains per sigloi, has Amurritum, servant of Ikun-pi-Istar, received on loan from Ilum-nasir. In the third month she shall pay the silver.” 1 sigloi=8.3 grams.

The loans were made at reduced below-market interest rates, lower than those offered on loans given by private individuals, and sometimes arrangements were made for the creditor to make food donations to the temple instead of repaying interest. Cuneiform records of the house of Egibi of Babylonia describe the families financial activities dated as having occurred sometime after 1000 B.C. and ending sometime during the reign of Darius I, show a “lending house” a family engaging in “professional banking.”

Property in Mesopotamia

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica:“The god of a city was originally owner of its land, which encircled it with an inner ring of irrigable arable land and an outer fringe of pasture, and the citizens were his tenants. The god and his viceregent, the king, had long ceased to disturb tenancy, and were content with fixed dues in naturalia, stock, money or service. One of the earliest monuments records the purchase by a king of a large estate for his son, paying a fair market price and adding a handsome honorarium to the many owners in costly garments, plate, and precious articles of furniture. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 ]

zavazi hematite

The Hammurbai Code “recognizes complete private ownership in land, but apparently extends the right to hold land to votaries, merchants (and resident aliens?). But all land was sold subject to its fixed charges. The king, however, could free land from these charges by charter, which was a frequent way of rewarding those who deserved well of the state. It is from these charters that we learn nearly all we know of the obligations that lay upon land. The state demanded men for the army and the corvee as well as dues in kind.

“A definite area was bound to find a bowman together with his linked pikeman (who bore the shield for both) and to furnish them with supplies for the campaign. This area was termed "a bow" as early as the 8th century B.C., but the usage was much earlier. Later, a horseman was due from certain areas. A man was only bound to serve so many (six?) times, but the land had to find a man annually. The service was usually discharged by slaves and serfs, but the amelu (and perhaps the muskenu) went to war. The "bows" were grouped in tens and hundreds. The corvee was less regular. The letters of Hammurabi often deal with claims to exemption. Religious officials and shepherds in charge of flocks were exempt. Special liabilities lay upon riparian owners to repair canals, bridges, quays, etc.

See Separate Article: PROPERTY, CONTRACTS AND BUSINESS LAWS IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ; ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN HOUSES africame.factsanddetails.com

Letters to Landlords in Babylonia

The following is a letter written by a Babylonian tenant to his landlord: “To my lord says Ibgatum, your servant. As, my lord, you have heard, an enemy has carried away my oxen. Though I never before wrote to you, my lord, now I send this letter (literally tablet). O my lord, send me a cow! I will lie up five shekels of silver and send them to my lord, even to you. O my lord, by the command of Marduk you determine whatever place you prefer (to be in); no one can hinder you, my lord. O my lord, as I will send you by night the five shekels of silver which I am tying up, so do you put them away at night. O my lord, grant my request and do glorify my head, and in the sight of my brethren my head shall not be humbled. As to what I send you, O my lord, my lord will not be angry (?). I am your servant; your wishes, O my lord, I have performed superabundantly; therefore entrust me with the cow which you, my lord, shall send, and in the town of Uru-Batsu your name, O my lord, shall be celebrated for ever. If you, my lord, will grant me this favor, send [the cow] with Ili-ikisam my brother, and let it come, and I will work diligently at the business of my lord, if he will send the cow. I am tying up the five shekels of silver and am sending them in all haste to you, my lord.” [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Ibgatum was evidently the lessee of a farm, and he does his best to get a cow out of his landlord in order to make up for the loss of his oxen. The 5 shekels probably represented the rent due to the landlord, and his promptitude in sending them was one of the arguments he used to get the cow. The word rendered “tie up” means literally “to yoke,” so that the shekels would appear to have been in the form of rings rather than bars of metal.

A letter in the collection of Sir Henry Peck, which has been translated by Mr. Pinches, is addressed to the landlord by his agent or factor, whose duty it was to look after his country estates. It runs as follows: “Letter from Daian-bel-ussur to Sirku my lord. I pray to-day to Bel and Nebo for the preservation of the life of my lord. As regards the oxen which my lord has sent, Bel and Nebo know that there is an ox [among them] for them from thee. I have made the irrigation-channel and wall. I have seen thy servant with the sheep, and thy servant with the oxen; order also that an ox may be brought up thence [as an offering?] unto Nebo, for I have not purchased a single ox for money. I saw fifty-six of them on the 20th day, when I offered sacrifice to Samas. I have caused twenty head to be sent from his hands to my lord. As for the garlic, which my lord bought from the governor, the owner of the field took possession of it when [the sellers] had gone away, and the governor of the district sold it for silver; so the plantations also I am guarding there [?], and my lord has asked: Why hast thou not sent my messenger and [why] hast thou measured the ground? about this also I send thee word. Let a messenger take and deliver [?] thy message.” Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024