ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN COOKING

Akkadian feasting scene

''The common man in Mesopotamia at the time of Hammurabi ate very sparingly,'' William W. Hallo, the curator of the Yale Babylonian Collection, told the New York Times. ''Large portions of the population had a subsistence diet. These recipes are for fancy dishes, perhaps even intended for a deity in statue form.'' [Source: Chris King, New York Times, November 18, 2001]

Boiling the meat into stew with spices and other ingredients was the basic culinary technique. A few of the recipes are identified as vegetarian, though — an ancient precursor, perhaps, to the modern vegetarian who still eats fish or chicken — some of them contain meat. Garlic, coriander and mint appear in these recipes, as does cumin, a spice that has retained its ancient name to the present day.

Those who enjoy alcohol with their food will be glad to know that, according to Mr. Hallo, beer was a ''crucial component of Mesopotamian cuisine.'' One cylinder seal that has been dated as slightly more ancient than the Larsa recipes depicts beer drinkers tugging directly from the vats through lengthy straws.

Meats was often eaten at festival and after religious ceremonies. ''Large numbers of animals were slaughtered, ostensibly in honor of a deity,'' Mr. Hallo said. ''The priests would then serve the deity in the form of a statue, draw a curtain, and allow it to eat its fill. Then the curtain would be opened and the priests would eat what was left. And, since statues don't eat much in Mesopotamia, the priests and their favored retainers must have eaten pretty well.''

Mesopotamia had its share of legendary feasts. A banquet held in the ninth century B.C. by the Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II, according to records found inscribed on a brick, drew 69,574 guests. Over 10 days they consumed 25,000 lambs and sheep, 500 stags, 500 gazelles, 30,000 birds, 10,000 eggs, 10,000 loaves of bread and thousands of gallons of wine and beer.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Oldest Cuisine in the World” by Jean Bottéro (2002) Amazon.com;

“Authentic Garum Recipe: A Selection Of Historical Recipes From Ancient Mesopotamia And More” by Hans Gimse (2021) Amazon.com;

“Flavors of Mesopotamia Culinary Delights in the Cradle of Civilization”

by Oriental Publishing (2024) Amazon.com;

“Pickles: From Ancient Mesopotamia to Your Homemade Pickle Jar” by Barrett Williams, ChatGPT Amazon.com;

“Culinary Technology of the Ancient Near East From the Neolithic to the Early Roman Period” by Jill L. Baker (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Cooking: Palaeolithic and Neolithic Cooking”

by Ferran Adrià (2021) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Cookery, Recipes and History,” by Jane Renfrew (English Heritage, 2006) Amazon.com

“The Oldest Kitchen in the World: 4,000 Years of Middle Eastern Cooking Passed Down through Generations” (A Cookbook) by Matay de Mayee (2024) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

Babylonian Cooking

In the article on the Yale culinary tablets, AP reported: “Although damaged to different degrees, they provide cooking instructions for more than two dozen Mesopotamian dishes, among them stews of pigeon, lamb or spleen, a turnip dish and a kind of poultry pie. Written on the best-preserved of the tablets are 25 recipes, 21 for meat and 4 for vegetables. Instructions call for most of the food to be prepared with water and fats, and to simmer for a long time in a covered pot, Mr. Bottero said. [Source: The Associated Press, January 03, 1988]

course bread, probably the staple food

There are 35 recipes in all. Most are for more meat stews, part, which suggests that the recipes were designed for the upper classes, the only people that could afford meat.

The tablets ''have revealed a cuisine of striking richness, refinement, sophistication and artistry, which is surprising from such an early period,'' Jean Bottero, a French Assyriologist, wrote in Biblical Archaeologist magazine in March 1985. ''Previously we would not have dared to think a cuisine 4,000 years old was so advanced.''

Mr. Bottero, who is a gourmet cook, has expressed doubt, however, over the dishes' palatability for modern tastes. Mesopotamians ''adored their food soaked in fats and oils,'' he wrote. ''They seem obsessed with every member of the onion family, and in contrast to our tastes, salt played a rather minor role in their diet.''

Meats included stag, gazelle, kid, lamb, mutton, squab and a bird called tarru. Frequently mentioned seasonings included onions, garlic and leeks, while stews were often thickened with grains, milk, beer or animal blood. Salt was sometimes mentioned. Scholars have not been able to identify all the ingredients, including tarru and two seasonings called samidu and suhutinnu. ''What is striking about all this is the multiplicity of condiments that were added to one and the same dish and the care with which they were combined into a blend of often complimentary flavors,'' Mr. Bottero wrote in a 1987 issue of the Journal of the American Oriental Society. ''These combinations obviously presume a demanding and refined palate - even when far removed from ours - betraying an authentic preoccupation with the gastronomic arts.'' ''I thought Hallo said when Bottero “tried to cook some of these recipes, he said he wouldn't serve that food to his worst enemies.''

Yale Recipes

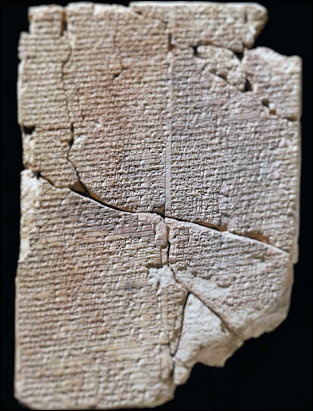

Laura Kelley wrote in Saudi Aramco World: “Tablet YBC 4644 has 25 recipes and two others, YBC 8958 and YBC 4648, contain 10 more. In addition to these sources, scholars generally acknowledge that there are two earlier recipes, one from Mari, Syria for a confection known as mersu, and the other probably from Uruk, also in Syria, for what has been interpreted as “court bouillon.”[Source: Laura Kelley, Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com /+/]

Yale recipe

“The Yale recipes were first translated by French historian Jean Bottéro and published in 1995 in Textes Culinaires Mésopotamiens. In Bottéro’s view, the dishes that can be discerned from the tablets are rich in meat and onions—particularly onions, which he calls the characteristic ingredient of the cuisine. He translated the recipes of YBC 4644 into 25 broths or porridges: 21 were meat- or fowl-based, and four were vegetable-based. All featured onions, garlic and leeks. /+/

“When I first read Textes Culinaires Mésopotamiens, I remember being disappointed that one of the greatest kingdoms on earth apparently had such dull food. Why, I wondered, when they had contact with civilizations all around western Asia, the Levant and North Africa, possibly even southern Asia, would they eat so many onions? Bottéro himself pronounced the food fit only for his worst enemies. /+/

“Although a pioneer in the interpretation of Mesopotamian cuisine, Bottéro did not claim certainty in many of his culinary translations, and some ingredients he left untranslated altogether. This makes reconstruction of actual recipes extraordinarily challenging. For example, one of the untranslated ingredients used in almost every recipe is samidu. Bottéro assumed that it was in the allium family, which includes onions, garlic, chives and leeks. Looking to modern languages, however, I found that in Hebrew and Syrian, semida means “fine meal” and, in Greek, semidalis is used to denote “the finest flour.” According to the University of Chicago’s Assyrian Dictionary, semidu is also defined as semolina.” /+/

Mesopotamian Ingredients

Laura Kelly wrote in Saudi Aramco World: “Several of the recipes feature an ingredient called kasû, which was interpreted as dodder, a parasitic weed of the genus Cuscuta. Puzzled by the use of a bitter weed in these dishes, I found an alternate meaning in a paper by Near Eastern scholar Piotr Steinkeller, who argued that kasû was probably wild licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra), and that it was used by the Mesopotamians both in cooking and in making beer. Also, mersu was interpreted as a cake because of the similarity between that word and marâsu, which means “to mix,” and because mersu was described as comprised of nuts and dates. Yet there is nothing to imply that mersu was a cake, let alone any instructions on how to make it.[Source: Laura Kelley, Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com Laura Kelley (laurakelley@silkroadgourmet.com) has long enjoyed food, travel and cultures. She is author of The Silk Road Gourmet, Vol. 1, Western and Southern Asia, available at www.silkroadgourmet.com]

lentils

On the Mesopotamia ingredients she deciphered, Kelly wrote in silkroadgourmet.com: “Andahsu = Wild tulip bulb. Multiple references to spring root vegetable and some statements about commonness in the north (Anatolia and Assyria) but uncommonness in the south. Not sure of the species of tulip that this refers to, but many are edible and have a distinct mildly bitter flavor. Possible also that it could refer to a wild crocus or lily bulb. [Source:Laura Kelly, silkroadgourmet.com, March 16, 2010, silkroadgourmet.com/tag/mesopotamia ]

“Halazzu = Carob Seeds. Halla: Refers to a plant that resembles the dung of birds in Assyrian. Zu or ze refers to the dung, but is also used in a prefix to denote plants or seeds. In old scholarly writings on the subject, there is a lot of reference to the “dove’s dung” mentioned in the Bible. It is possible also that the “ingredient” is a carob syrup or carob powder given Bottero’s statement about pressing or squeezing the unknown plant. However, this could also be his interpretation of the Akkadian word halasu which mean to crush or extract and is often found in reference to the making of seed-oil. Carob is widely enjoyed across Western Asia, Levant and Eastern Mediterranean today and imparts a sweet chocolate-like flavor to dishes.

“Zibu = Black Onion Seeds (nigella sativa) (Not black cumin (Carum bulbocastanum) which is from the N. India/Himalayas). “Black onion seeds” or kalonji as they are called in many places on the Indian Subcontinent are not really onion seeds at all, but flower seeds that impart a strong flavor reminiscent to onions by some people. These seeds have been used in Mesopotamian and Egyptian food and are still used widely in Indian, Persian and Turkish foods today. “Butumtu = Pistachio Nuts or Flour. Buttutu is Assyrian for Pistachio nuts. Butumtu is synonymous. In Textes Culinaire Mesopotamien (TCM), Bottero called these green or unripened wheat or barley, in The Oldest Cuisine in the World (OCW) he calls these husked lentils.

“Nuhurtu = Asafoetida. This is one undefined ingredient in Bottero’s work that really will impart a complex onion-like flavor to a dish. The principal reference is Thompson DAB, but his opinion is supported by many references to the medicinal use of the plant’s roots and resin (ref 1). It is also listed in the catalog of “trees” in Assurnasipal II royal garden at Kalhu. Since asafoetida plants grow quite large it is understandable that it was thought to be a tree.”

Mesopotamian Dishes

Laura Kelly wrote in silkroadgourmet.com: “Mersu = A confection with dates. It could also be simply a layer of pounded dates rolled into a sheet which is then covered with nuts, then rolled and sliced, or pounded dates rolled into balls and covered with chopped nuts. If one adds flour, it could possibly be something like the modern Iranian Ranginak in which dates stuffed with nuts are enclosed within a thin dough sandwich and sliced, or the Lebanese Ma’moul in which pounded date cores are rolled in a layer of semolina which is then covered with chopped nuts. Bottero called this a cake. [Source: Laura Kelly, silkroadgourmet.com, March 16, 2010, silkroadgourmet.com/tag/mesopotamia ]

Kelly wrote Saudi Aramco World: “A look at modern western Asian and Levantine cuisines hints that mersu could easily have been a date-nut roll, or a beautiful date “candy,” as well. Both sweets are based on pounded dates and chopped nuts or other fruit or nut toppings. Or, adding only some type of flour, mersu could resemble the modern Iranian dessert ranginak, which consists of dates stuffed with pistachios enclosed in a thin crust of dough. Or it could be like the modern Lebanese ma‘moul, which has a pounded-date center covered in a layer of semolina that is then covered in a layer of chopped pistachios. Looking to non-European cuisines shows us the many possible, culturally plausible variations for mersu other than “cake.” [Source: Laura Kelley, Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com ]

“Sebtu-rolls = Roasted Dill Seed. Dill (Anethum graveolens) was called sibetum in Assyrian (ref 1). Bottero states that these were probably grain rolls (small pieces of bread) eaten as a staple with meals. Several recipes state that these are roasted in an oven and scattered about the dish just before presentation. Both the etymology and the use make it unlikely that these were rolls of grain. I believe the confusion comes from the translation of the word “roll” which I take to mean seed (as opposed to dill weed). In Tablet B and C of the Yale collection Bottero mentions using dough to make sebtu rolls and bake them in the oven. My interpretation of this is that roasted dill seed is added to the dough for flavor.

Relief from Ashurbanipal's palace at Nineveh 7th century BC

Mesopotamian Recipes

Hand-size tablets describe recipes for spicy meat and vegetable stews of gazelle, kid, pigeon, partridge and turnip, as well as for pies and garnishes that suggest. John Lawton wrote in Aramco World: “The best preserved of the tablets measures a little more than 12 by 16 centimeters (4 ¾ by 6 ½ in.), and features 21 meat-based and four vegetable-based stews, identified very much as dishes are today by their main ingredient ("stew of stag"), their appearance ("glistening" or "crumbly") or their place of origin: An "Assyrian stew" comes from the northern part of the country, while an "Elamite stew" is borrowed from neighbors in what is now the southwestern corner of Iran. [Source: John Lawton, Aramco World, April 6, 2011 /~/]

“Telegraphic and concise, these recipes are not for the culinary amateur. Often just a few lines long, they summarize essential steps and ingredients, laconically ignoring quantities and cooking times, which their users were apparently expected to know from experience. A far cry from the cookbooks of today, they were not meant to guide the housewife, Bottéro believes, but mainly to standardize and even ritualize cooking procedures.” /~/

Laura Kelly wrote in Saudi Aramco World:“My current research, and kitchen experimentation by myself and others, is providing some revised interpretations of the Yale tablet recipes. In fact, I don’t think that any of the recipes on YBC 4644 represent either broths or porridges; rather, they are general guidelines for the flavors of dishes that range from stew-like koreshes, curries and soups to braised meats and dry pilafs. It all depends on the relative proportions of liquid and solid ingredients. As noted earlier, amounts of ingredients are almost always absent from these recipes, so the exact dish prepared is left up to the cook—who is assumed to have sufficient training to understand and use the recipes in this form. [Source: Laura Kelley,Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com /+/]

“For example, Recipe 19 on YBC 4644 is for halazzu, which is untranslated. I believe it to be a recipe for lamb or beef with carob: Halazzu was proposed as carob by several previous Assyriologists, and substituting “carob” for it in the recipe makes for a delicious stew or sauce. Recipe 20, called “salted broth,” I interpret as mutton with wild licorice and juniper; Recipe 23, for kanasu—another term left untranslated—I think is lamb with grain and mint. Lastly, I have found a delicious grain and herb pilaf in Recipe 25 by using the alternative definition of laptu, which Bottéro translated as “turnip” without mentioning that “barley” is an equally accepted translation among scholars. /+/

“In addition to new interpretations for recipes, I also found a rich source for other recipes in translations of texts about foods prepared as offerings for gods. According to Vanderbilt University scholar Jack M. Sasson, the intimate connection between the Mesopotamians and their deities makes it reasonable to assume a connection between foods offered to the gods and those enjoyed on home tables—or at least those served to the elite, for the elite also ate from the divine table, thus providing an added incentive to delight the palate. For instance, Marcel Sigrist’s translations of offerings at the Mesopotamian city of Nippur give several more ingredients for mersu, such as figs, raisins, minced apples, minced garlic, oil or butter, soft or hard cheese, and wine must or syrup. This widens the field of variation for the dish and allows cooks to mix and match combinations of ingredients. Also from the same paper is a recipe for a bread called ninda-gal that lists sumac, saffron and onion seeds as ingredients. In addition to being new sources for recipes, these offerings may also provide insight into some of the foods eaten by Mesopotamian people.” /+/

Assyrian banquet

Mesopotamian Cooking and Food Preparation

John Lawton wrote in Aramco World: Two tablets are “detailed and scrupulous in describing the various cooking operations. Unfortunately, they are full of breaks and illegible portions; few of the recipes are complete. They include mainly bird dishes, but also deal in detail with various cereal and vegetable side dishes. [Source: John Lawton, Aramco World, April 6, 2011 /~/]

“Preparation of these meals was complex, calling in different recipes for operations like mixing, sprinkling, slicing, squeezing, pounding, steeping, shredding, crumbling, straining and marinating. Along with the number of steps involved, this complexity implies the availability of a wide selection of kitchen implements and ample culinary installations - both features more likely to be found in a temple or palace than in a private household. /~/

“Heat for cooking was provided primarily by an oven - although grilled and roasted meat were also common. Bread and pastry were baked in the oven and pots were placed over the oven's opening to bring liquids to the boil. Two vessels were invented, or refined, by the Mesopotamians to allow cooking in a liquid medium: the metal cauldron, for quick, pre-cooking steps such as browning, and a closed clay pot for simmering. "All these details," says Bottéro, writing in a recent issue of The Journal of the American Oriental Society, "show how far the Babylonians had developed the art of cooking, clearly to satisfy refined and gastronomical concerns." /~/

“The Mesopotamians, for example, prepared a fermented sauce, which they called siqqu, from fish, shellfish and grasshoppers for both kitchen and table use. They also had knowledge of the lactic fermentation needed to make cream cheese. In their cooking, spices abound. No recipe contains fewer than three condiments, some contain as many as 10 - all added with care and combined into a blend of often complementary flavors. "These combinations," says Bottéro, "obviously presume a demanding and refined palate, betraying an authentic preoccupation with the gastronomic arts." /~/

Cooking Mesopotamian Recipes

Laura Kelly wrote in Saudi Aramco World:“These ancient recipes are a fascinating challenge for modern cooks—not only because they are a window into the food culture of ancient Mesopotamia, but also because they are actually little more than lists of ingredients, usually with scant information on the amounts of ingredients to use, their form, or even how to prepare the dishes. Although difficult for some to navigate, the recipes allow for a great deal of creativity in using what is on hand or in reinterpreting dishes with favorite local and personal flavors. (In medieval Europe, recipes were typically written like this, and outside the industrialized world they still are.) [Source: Laura Kelley,Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com /+/]

“Assisted by a small group of chefs and cooks from three continents, I recently explored these and other Mesopotamian recipes. I cooked a lamb and carob stew, lamb chops with carob sauce, hen with herbs (from YBC 8958), barley and herb pilaf and several mersu variations. Others cooked lamb with grain and mint (substituting barley for couscous or wheatberries, the most likely forms of emmer grain used in the recipe), several variations of lamb with licorice and juniper, and pork tenderloin with licorice and citron. /+/

“So how did these reinterpreted dishes taste? In a word—delicious. The flavors are unusual and complex, but enjoyable, tasting as if they could have been created by a skilled modern chef. Far from being suited to an enemy, these dishes are best shared with a dear friend.” /+/

John Lawton wrote in Aramco World: “The staff of the Frerch magazine Actuel carried imagination into practice recently to cook, photograph and eat the pie whose recipe is on page five. They called it "a real treat," but Bottéro, who has always refused to put the recipes to the test himself, is not impressed. For one thing, the Assyriologist-chef believes, the Mesopotamians' concept of good food was not only worlds away from ours in time, but also in taste. They liked their food soaked in fats and oils, seemed obsessed with every member of the onion family and may have used much less salt than we do today.” [Source: John Lawton, Aramco World, April 6, 2011 /~/]

3,700-Year-Old Mesopotamia Dishes

Listed below are translations of three of the world’s oldest known recipes, recorded 3,700 years ago by an Akkadian scribe. Elaborations have been added in brackets to enhance the meaning of the originals. “Kid Stew: Singe head, legs and tail over flame [before putting in pot]. Meat [in addition to kid] is needed, [preferably mutton to sharpen the flavor]. Bring water to boil. Throw in fat. Squeeze onion, samîdu [a plant probably of the onion family, and] garlic [to extract juices, add to pot with] blood and soured milk. [Add] an equal amount of raw šuhutinnu [another plant probably of the onion family] and serve. [Source: John Lawton, Aramco World, March/April 1988, on pages 4-13 /~/]

“Tarru-Bird Stew: [Besides the tarru birds, which may have been pigeon, quail or partridge,] meat from a fresh leg of mutton is needed. Boil the water, throw fat in. Dress the tarru [and place in pot]. Add coarse salt as needed. [Add] hulled cake of malt. Squeeze onions, samîdu, leek, garlic [together] and add to pot along with] milk. After [cooking and] cutting up the tarru , plunge them [to braise] in stock [from the pot]. Then place them back in the pot [in order to finish cooking]. To be brought out for carving. /~/

“Braised Turnips: Meat is not needed. Boil water. Throw fat in. [Add] onion, dorsal thorn [name of unknown plant used as seasoning], coriander, cumin and kanašû [a legume]. Squeeze leek and garlic and spread [juice] on dish. Add onion and mint.”

On a meat pie baked in an unleavened crust, made by a recipe on a cuneiform tablet produced around the same time as the recipes above, John Lawton wrote in Aramco World: "Carefully lay out the fowls on a platter; spread over them the chopped pieces of gizzard and pluck, as well as the small sêpêtu breads which have been backed in the oven; sprinkle the whole with sauce, cover with the prepared crust and send to the table...Stirred into the dough were various condiments and aromatic ingredients that enhanced the taste. The pie's filling was composed of small fowls - we don't know whether they were wild or domestic fowl, land-, water-or seabirds - cooked in a spicy sauce with their own gizzards and pluck, or livers, hearts and lungs. The result must have been a little like giblet gravy. And when the dish was served, it was garnished with small flat bread loaves that were also specially flavored - not too different from the bread stuffing we eat with fowl.” /~/

Scientifically Recreating the World’s Oldest-Known Recipes

In 2019, scientists recreated four ancient Mesopotamian dishes based on Yale tablets, three of which dated to around 1730 B.C., and a fourth from about 1,000 years later. Of the older three tablets, the most intact one lists the ingredients for 25 recipes of stews and broths; the other two contain an additional 10 or so recipes. These two have more detailed cooking instructions and presentation suggestions, but they are broken and therefore not completely readable. [Source: Ashley Winchester, BBC, November 5, 2019]

“They’re not very informative recipes — maybe four lines long — so you are making a lot of assumptions,” Pia Sorensen, a Harvard University food chemist told the BBC, She worked, with Harvard Science and Cooking Fellow Patricia Jurado Gonzalez, on perfecting the proportions of ingredients using a scientific approach with hypotheses, controls and variables. “All of the food materials today and 4,000 years ago are the same: a piece of meat is basically a piece of meat. From a physics point of view, the process is the same. There is a science there that is the same today as it was 4,000 years ago,” Jurado Gonzalez said.

Ashley Winchester of the BBC wrote: The food scientists used what they know about human tastes, preparation essentials that don’t drastically change over time, and what they hypothesised might be correct ingredient proportions to come up with their best guess as to the closest approximation of an authentic recipe. “This idea that we can be guided by what works — if it’s too liquidy, it’s going to be a soup. By looking at the material parameters, we can zoom in on what it is” — in most cases, a stew, Sorensen said.

Recreating Mesopotamian Lamb Stew and Tuh’u

Ashley Winchester on the BBC wrote: The lamb stew, me-e puhadi, is meant to be eaten with barley cakes crumbled into the liquid, as one might do today with bread to sop up a soup. The scholars’ resulting version of the dish offers a hearty taste and texture teased out from months of trial and error and by using the scientific method of variables and controls to unravel the recipe’s mysteries. They realised, for example, when the inclusion of soapwort, a perennial plant sometimes used as a mild soap, was a mistranslation: adding this ingredient in any measure made the resulting dish bitter, frothy and unpalatable. Similarly, levels of seasonings have a threshold: there is an amount of salt in any dish, whether 4,000 years ago or today, that will render it inedible, they said. [Source: Ashley Winchester, BBC, November 5, 2019]

Tuh’u red beetroots and is somewhat similar to borscht

Tuh'u Recipe:

Ingredients:

1 pound leg of mutton, diced

½ cups rendered sheep fat

1 small onion, chopped

½ teaspoons salt

1 pound beetroot, peeled and diced

1 cups rocket, chopped

½ cups fresh coriander, chopped

1 cups Persian shallot, chopped

1 teaspoons cumin seeds

1 cups beer (a mix of sour beer & German Weißbier)

½ cups water

½ cups leek, chopped

2 garlic cloves, peeled and crushed

For the garnish:

½ cups fresh coriander, finely chopped

½ cups kurrat (or spring leek), finely chopped

2 teaspoons coriander seeds, coarsely crushed

[Source: Food in Ancient Mesopotamia, Cooking the Yale Babylonian Culinary Recipes, co-author and translator Gojko Barjamovic.

Instructions: Heat sheep fat in a pot wide enough for the diced lamb to spread in one layer. Add lamb and sear on high heat until all moisture evaporates. Fold in the onion and keep cooking until it is almost transparent. Fold in salt, beetroot, rocket, fresh coriander, Persian shallot and cumin. Keep on folding until the moisture evaporates. Pour in beer, and then add water. Give the mixture a light stir and then bring to a boil. Reduce heat and add leek and garlic. Allow to simmer for about an hour until the sauce thickens.

Pound kurrat and remaining fresh coriander into a paste using a mortar and pestle. Ladle the stew into bowls and sprinkle with coriander seeds and kurrat and fresh coriander paste. The dish can be served with steamed bulgur, boiled chickpeas and bread.

Recipe for Ancient Mesopotamian Pigeon Stew

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: The earliest known recipes, by many centuries, are found on three tablets dating to the Old Babylonian period. Though seemingly simple, their minimal instructions could only have been followed by experienced chefs working for the highest echelons of society. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

One tablet features 25 recipes for stews and soups, both meat and vegetarian, including some directions — though no measurements or cooking times — for an amursanu-pigeon stew:

Split the pigeon in half — add other meat.

Prepare the water, add fat and salt to taste;

Breadcrumbs, onion, samidu, leeks, and garlic

(first soak the herbs in milk).

When it is cooked, it is ready to serve.

“With the exception of amursanu, which is probably a type of pigeon, and samidu, an unknown spice, the ingredients are certainly recognizable. But the dish would, in fact, be impossible to replicate, says Benjamin Foster, curator of the Yale Babylonian Collection. “People often think that because they can cook Arab or Persian food that they can make this stuff, but they don’t know how much regional cooking was changed by the Muslim conquests. If you cook these up using modern Near Eastern ingredients, it is pure fantasy — but often delicious.”

Mesopotamian-Style Fowl

Laura Kelly wrote in Saudi Aramco World: “Ingredients from the tablet: pigeon, salt, water, fat, vinegar, semolina, leek, garlic, shallots, tulip bulb, yogurt or sour cream, and “greens.” As with all Mesopotamian recipes, how these are put together, and in what quantities, is up to you. For this substitute Cornish game hen for pigeon.

2 Cornish game hens, cleaned and salted inside and out

4 cups water

2 cups chicken stock

1 cups pomegranate vinegar

3 tablespoons butter

¼ teaspoon asafetida

2 teaspoons dried mint

2 tablespoons coriander seed

1 teaspoons cumin seeds

1 large Sri Lankan cinnamon stick

1 handful baby arugula, chopped

½ yellow onion

1 leek, white and green parts, well cleaned

10-11 garlic cloves peeled

½ cups lightly drained yogurt

3 handfuls of fresh mint leaves

1 handful of fresh sage

Water to moisten herbs; More pomegranate vinegar to rinse hens; 1-3 tsps. semolina to thicken sauce. [Source: Laura Kelley,Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com /+/]

“Clean and dry fowl and salt liberally, inside and out. Set aside. Prepare water, stock and vinegar in a large stockpot or kettle large enough to hold the hens. Add butter, asafetida, mint and arugula, and heat over a high flame, stirring occasionally. When the water has come to a boil, add the hens and return to a boil. Reduce heat a bit and cook uncovered over medium heat for 5 minutes. Then reduce heat till liquid just bubbles. Cover and cook for 5 minutes. /+/

“In a food processor, pulse together the onion, leek, 6 to 7 cloves of garlic and lightly drained yogurt until it is a small dice or mince. Add it to the water and chickens, and continue to cook for another 5 to 10 minutes; do not overcook. Total cooking time for hens in the pot is 15 to 20 minutes. When done, remove birds from the pot and set aside until cool enough to handle. /+/

“Preheat broiler to high. While cooling the hens, take the stock you used to cook the hens and pour it into a clean saucepan. If you are using a cup or two of stock to make couscous, barley or some other grain, do so now and pour off about one-third to one-half of the stock that remains. Heat to a steady low boil, stirring constantly, and cook uncovered to reduce, stirring occasionally. /+/

“Pulse the mint and sage (or other herbs you choose) with the remaining garlic in the food processor a few times until nicely minced and add a teaspoon or so of water to moisten them. Divide hens in two, down the spine, by slicing with a large, sharp knife or cleaver. Pour pomegranate vinegar over the hens, inside and out, to wash away herbs from cooking and set aside. Rub both sides of the hens with the mint and sage herb mixture until an even coating is achieved and set aside. Continue to cook stock until it starts to thicken. Add semolina to facilitate this process; stir until dissolved. /+/

“Place hens rib side down on a lightly sprayed baking sheet. Cook under the preheated broiler flame 4 to 5 minutes per side. Watch constantly and be careful not to burn the hens. Turn baking sheet as necessary to ensure even cooking. When done, remove from heat and let rest 5 to 10 minutes while finishing the sauce. If desired, strain the sauce. (I did not, preferring a more rustic presentation.) I served the dish in a shallow bowl, adding a layer of roasted barley and herb pilaf and sauce beneath the hen and a bit of sauce on the fowl. /+/

Roasted Barley and Herb Pilaf

Laura Kelly wrote in Saudi Aramco World:“Yale Babylonian Collection 4644, Recipe 25: Ingredients from the tablet: water, fat, roasted barley, mix of chopped shallots, arugula, and coriander, semolina, blood, mashed leeks and garlic. 1 c. whole barley, cleaned 2 c. water; 1 c. prepared stock; 2 tsps. of butter; 1 tsp. salt; ¼ tsp. asafetida; 1 tsp. ground coriander; 3 shallots, peeled; 1 handful of baby arugula; 2 tsps. semolina; 2 tsps. blood (optional, if available); 1 leek, white and green parts, well cleaned; 4-5 garlic cloves, peeled. [Source: Laura Kelley,Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com /+/]

“Preheat broiler to the highest setting. Spread the cleaned barley on a baking sheet to form a single layer of grain. Place barley under broiler flame and leave for a few minutes until it starts to smoke and color. Stir lightly and turn pan if necessary until most barley is tan in color. Be careful not to burn the grain. Properly roasted barley will taste nutty. When done, remove from flame and let cool. /+/

“Add water and prepared stock to a medium saucepan. You may season the stock any way you wish, or use the cooking stock from another recipe. (I used the stock from the hen recipe above.) Add butter, salt, asafetida and ground coriander, and continue to heat. /+/

“In a food processor, pulse shallots and arugula once or twice. Then add the semolina and blood, and pulse one or two more times. Add this mixture to the heating, water and stir. When just short of a boil, add the barley and stir well. Bring back to a boil. Then reduce heat, cover and cook over a medium-low flame until about three-quarters done—20 to 30 minutes. /+/

“As the barley is cooking, pulse leeks and garlic two to four times until minced but not mushy. Add this to the barley and stir once or twice—not too much or barley will be soggy. Partially re-cover saucepan and continue to cook, checking frequently. It should be done or nearly done within 10 minutes. /+/

At least one modern cook has tried to recreate one of the recipes. Alexandra Hicks, an officer of the American Herb Society and a food historian at the University of Michigan, prepared a stew of kippu, a type of fowl, for 150 guests at a meeting of the American Oriental Society, Mr. Hallo said. ''The results,'' Mr. Hallo told the New York Times, ''were adjudged to be not only historic but also, what shall we say, delicious.'' [Source: Chris King, New York Times, November 18, 2001]

Chris King wrote in the New York Times, “Certain key elements to a helpful recipe were not provided, such as the amounts of the ingredients or how long any stage of the dish should simmer before proceeding to the next step. It is presumed that oral tradition filled in those gaps. Scholars also are left to guess how to translate many of the ingredients, though various fowl seemed to be favored, and it is known from other contemporary texts that sheep and pigs also found their way into Mesopotamian pots.

''Unfortunately,'' Mr. Hallo chuckled, ''we're not quite sure what 'kippu' means. There are many candidates. We didn't think it was cormorant, so we decided on chicken.'' Though kippu was likely fowl, it could not have been turkey. According to Andrew F. Smith, a food historian who is writing ''a history of turkey as a cultural artifact,'' domesticated turkey was introduced to the Near East via Spain following Hernando Cortés's expedition in the Americas — some 34 centuries after the Larsa recipes were inscribed.

''Delights From the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine” was written by Nawal Nasrallah, a former professor of English literature who fled Iraq after the Iran-Iraq war in 1990. She traces Iraqi cookery back to the dawn of recorded history and the civilization that sprang up about 6000 B.C. in the Fertile Crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, where Sumerian mythology placed the mythical mound of creation and a tree of life in a garden that became known as Eden, and incorporated recipes from the 3,700-year-old Yale culinary tablets. [Source: Ralph Blumenthal, New York Times, April 2, 2003]

Pickled locusts and boiled heads of sheep aside, Ms. Nasrallah found a wealth of recipes for no fewer than 300 types of bread, 100 kinds of soup, medieval sandwiches that existed long before the Earl of Sandwich, and a fried eggplant casserole, al-buraniya, which she calls ''the mother of all moussakas.'' Her recipes include a flatbread described ''as ancient as the Sumerian civilization itself.''

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and Yale University

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024