STONE AGE MAN TO THE BEGINNING OF CIVILIZED MAN

Stone Age Man

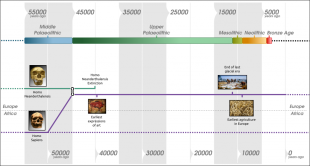

The jump from stone-age man (primitive man, early modern man or Cro-Magnon Man, whatever you want to call him) to civilized man is defined by some as taking place with the invention of agriculture around 10,000 to 8000 B.C., and by others with the development of writing around 3200 B.C. Yet others say it took place with the invention of metal tools (beginning with copper ones) around 4500 B.C.

Around 10,000 to 8,000 B.C. at sites scattered around the world, but mostly in the Near East, the cultivation of previously wild plants and the domestication of previously wild animals for work and food took place. Development of pottery vessels and cloth took place around the same time or not long afterwards. Among the results of these advancements were huge increases in the human population and control by mankind over the Earth.

The Neolithic period (from about 9500 to 6000 B.C.) was one in which people began using of polished stone tools and started shifting to agriculture from hunting and gathering. The shift from the nomadic life to one involving living in villages and farming is sometimes called the Neolithic Revolution, a term coined by the Australian archaeologist V. Gordon Childe. There is a debate among archaeologists as to what caused the Neolithic Revolution. The conventional view for a long time had been that change began taking place about 11,400 years ago when the last ice age came to an end and agriculture became possible, perhaps even necessary for survival. Some archaeologists disagree with this view and believe changes came about as human cognition and psychology changed.

The world population around 10,000 B.C. was between 5 million and 10 million. By 3000 B.C. It was 100 million. Archaeologists have estimated that no more than 20,000 people and maybe as few as 1,600 people lived in France at one time during Paleolithic times. Anthropologist J. Lawrence Angel discovered that 30,000 years ago men averaged 5 feet 11 and women averaged 5 foot 6. In Greco-Roman times men were 5 foot 6 and women were 5 foot 0. In 1960, American men were 5 foot 9. Angel also estimated that on average men lived to be 33.3 years old and women 28.7 years old during paleolithic times and that men had lost an average of 2.2 teeth when died: 3.5 teeth in 6,500 B.C.; 6.6 missing in Roman times.

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity” by David Graeber and David Wengrow Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Humans at the End of the Ice Age: The Archaeology of the Pleistocene—Holocene Transition” by Lawrence Guy Straus, Berit Valentin Eriksen (1996) Amazon.com

“Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age” by Erella Hovers, Steven Kuhn (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Mesolithic Europe” by Liv Nilsson Stutz, Rita Peyroteo Stjerna, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000–5000 BC” by Steven Mithen (2006) Amazon.com;

“Coastal Landscapes of the Mesolithic: Human Engagement with the Coast from the Atlantic to the Baltic Sea” by Almut Schülke (2020) Amazon.com;

“Mesolithic Europe” by Geoff Bailey and Penny Spikins (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe” by Andre Debenath , André Debénath , et al. Amazon.com

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013) Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Iberia: Genetics, Anthropology, and Linguistics” by Jorge Martínez-Laso, Eduardo Gómez-Casado (2000) Amazon.com;

“The British Palaeolithic: Human Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World” by Paul Pettitt, Mark White Amazon.com;

How Did Civilization Come About?

Matti Friedman wrote in Smithsonian magazine: How did civilization come about? Why, after millions of years of hunting and gathering and wandering in small bands, did people settle down and begin to raise crops and animals, eventually creating governing hierarchies, organized religions, urban architecture and the other advances that led to the industrial and technological societies of today? [Source: Matti Friedman, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2023]

Scholars still debate how and why the shift occurred, but many point to a crucial change 10,000 or so years ago, when people living in the area of eastern Turkey or northern Syria identified useful mutations in grains and figured out how to raise the crops they wanted instead of just collecting whatever happened to grow. The domestication of plants meant higher yields, which meant more people could live together and plan their futures, leading to the first permanent villages and towns, then to administrations in charge of managing harvests, then to systems of writing, engineering, trade, kingdoms, empires, democracies, bureaucracies and the IRS. Because this transformational leap took place at least 5,000 years before the advent of recorded history, we can’t know with confidence exactly what happened.

The Near East, the region between the eastern shores of the Mediterranean to present-day Afghanistan, is regarded as the cradle of pre-Mesopotamia culture. It was where agriculture began, the first animals were domesticated and the first villages were founded. Around 10,000 B.C. the Near East was largely occupied by nomads who hunted gazelle, goats, sheep and cattle and gathered grasses, cereals and fruits. At the end of the ice age it was originally thought the climate in the Near East was warmer and drier but in fact it was wetter. The landscape in the region was very different that it is today. Hills that are now barren and rocky may have been covered with dense forest. Herds of gazelles and other wild animals roamed about, Rivers and lakes teemed with ducks and geese and migratory birds. There were no towns or agricultural areas, Fruits and nuts and grains like barley and wheat grew wild. Humans were hunter-gatherers who migrated to where they could find food. They still used stone tools and live in primitive shelters or caves.

Neolithic Period

The Neolithic period (from about 10,000 to 6000 B.C.) was one in which people began using of polished stone tools and started shifting to agriculture from hunting and gathering. The shift from the nomadic life to one involving living in villages and farming is sometimes called the Neolithic Revolution (See Below). The Near East, the region between the eastern shores of the Mediterranean to present-day Afghanistan, is regarded as the cradle of pre-Mesopotamia culture. It was where agriculture began, the first animals were domesticated and the first villages were founded.

The jump from hunter-gatherers (stone-age man (primitive man, early modern man or Cro-Magnon Man) to more "civilized" man (farmers) is defined by some as taking place with the invention of agriculture around 10,000 to 8000 B.C., and by others with the development of writing around 3200 B.C. Yet others say it took place with the invention of metals tools (beginning with copper ones) around 4500 B.C.

Around 10,000 B.C. the Near East was largely occupied by nomads who hunted gazelle, goats, sheep and cattle and gathered grasses, cereals and fruits. At the end of the ice age it was originally thought the climate in the Near East was warmer and drier but in fact it was wetter. The landscape in the region was very different that it is today. Hills that are now barren and rocky may have been covered with dense forest. Herds of gazelles and other wild animals roamed about, Rivers and lakes teemed with ducks and geese and migratory birds. There were no towns or agricultural areas, Fruits and nuts and grains like barley and wheat grew wild. Humans were hunter-gatherers who migrated to where they could find food. They still used stone tools and live in primitive shelters or caves.

Around 10,000 to 8,000 B.C. at sites scattered around the world, but mostly in the Near East, the cultivation of previously wild plants and the domestication of previously wild animals for work and food took place. Development of pottery vessels and cloth took place not long afterwards. Among the results of these advancements were huge increases in the human population and control by mankind over the Earth.

The Neolithic Period was preceded by the Paleolithic Period. Te Paleolithic Period (about 3 million years to 10,000 B.C.) — also spelled Palaeolithic Period and also called Old Stone Age — is a cultural stage of human development, characterized by the use of chipped stone tools. The Paleolithic Period is divided into three period: 1) Lower Paleolithic Period (2,580,000 to 200,000 years ago); 2) Middle Paleolithic Period (about 200,000 years ago to about 40,000 years ago); 3) Upper Paleolithic Period (beginning about 40,000 years ago). The three subdivisions are generally defined by the types of tools used — and their corresponding levels of sophistication — in each period. The period is studied through archaeology, the biological sciences, and even metaphysical studies including theology. Archaeology supplies sufficient information to provide some insight into the minds of Neanderthals and early Modern Man (i.e. Cro Magnon Man) who lived during this time.

See Separate Article: PALEOLITHIC PERIOD europe.factsanddetails.com

Paleolithic to Chalcolithic Periods in the Near East (Middle East)

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: Here we “provide an overview of ancient Near Eastern history as reconstructed out of the researches of historians and archaeologists, first, from the Paleolithic to the Chalcolithic (Copper) periods. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

300,000 to 70,000 years ago

Lower Paleolithic

Nomadic Life

Pebble tools

Man discovers fire (200,000)

Bifacial tools Tabunian Cave on Mount Carmel;

Yarbrud in Syria

70,000 to 35,000 years ago

Middle Paleolithic

Nomadic Life

Mousterian flaked flints

Neanderthal Man, Galilee, Palestine; Mount Carmel, Palestine

35,000 years ago to 12,000 B.C.

Upper Paleolithic

Nomadic Life

Blade industries

"tepee" type dwellings, figurines, bone and ivory jewelry Wadi en-Natuf, Palestine; Shanidar, Iraq; Zawi Chemi, Iraq; Karim Shahir, Iraq

12,000 to 10,000 B.C.

Mesolithic

Hamlet Life

Natufian micro-flints, new weapons and tools, primitive agriculture, rock drawings and wall paintings, beginnings of sea travel, Wadi en-Natuf, Palestine; Deir Tasi, Egypt; Jarmo, Iraq; Tell Hassuna, Iraq

10,000 to 4,500 B.C.

Neolithic

Village Life

Extensive agriculture, domestication of animals, extensive trade, early shrines Jericho, Palestine; Deir Tasi, Egypt; Jarmo, Iraq; Tell Hassuna, Iraq

4,500 to 3,300 B.C.

Chalcolithic

Citys /States and Kingdoms

Copper and stone tools, pottery of varied styles, beginning of ziggurats, development of writing and mathematics, cylinder seals used, time of the "Flood", Egyptian nomes unite to form upper and lower Egypt

al Badari, Egypt; el Amrah, Egypt; Tepe Gawra, Iraq; Tell Halaf, Iraq; Eridu, Iraq; Beer-sheba, Palestine; Dead Sea Region

See Separate Article: STONE AGE PALESTINE africame. factsanddetails.com

Accelerated Evolution

The conventional wisdom for a long time was that humans had mastered their environments so well starting around 10,000 years ago, when agriculture was invented, it was no longer necessary to evolve. University of Michigan paleoanthropologist Milford Wolpoff told the Los Angeles Times, “People thought that with technology and culture there’d be no reason for physical things to make any difference. If you can ride a horse, it doesn’t matter if you can runs fast.”

But it turns nothing could be further from the truth: the speed of evolution for mankind is speeding up not slowing down, with some scientists estimating the pace is 100 times more than it was 10,000 years ago if no other reason than that there are many more people living in the world today. Wolpoff said, “When there’s more people, there are more mutations. And when there’s more mutations there’s more selection.”

In 2007, scientists compared 3 million genetic variants in the DNA of 269 people of African, Asian, European and North American descent and found 1,800 genes had been widely adopted in the last 40,000 years. Using more conservative methods, researchers came with 300 to 5000 variants, still a significant numbers. Among the changes that have occurred in the last 6,000 to 10,000 has been the introduction of blue eyes. That long ago nearly every one had brown eyes and blue eyes were non existent. Now there are half a billion people with them.

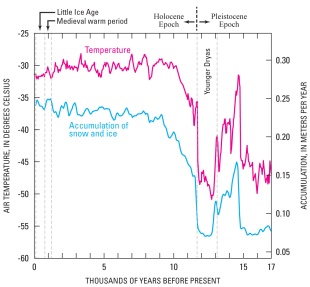

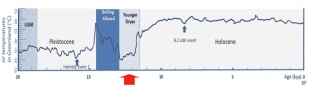

Younger Dryas Period (10,900 to 9600 B.C.)

The Younger Dryas, which began around 12,900 and lasted for 1,300 years, was a major cooling (stadial) event which temporarily marked a return to glacial conditions, during a time of climatic warming after maximum glaciation during the last and current Ice Age. The period before it — the Bølling–Allerød Interstadial (also known as the Late Glacial Interstadial — lasted from 14,670 to 12,900 years ago. The Younger Dryas was the most severe and longest lasting of several interruptions to the warming of the Earth's climate. The end of the Younger Dryas marks the beginning of the current Holocene epoch. [Source: Wikipedia]

The change during The Younger Dryas period was relatively sudden and took place over decades, resulting in a decline of temperatures in Greenland by 4–10 °C (7.2–18°F), and advances of glaciers and drier conditions over much of the temperate Northern Hemisphere and climatic changes around the globe. A number of hypotheses have been made to explain the cause. The one with the most support from scientists is that the ocean currents in Atlantic Ocean which bring warm water northward was disrupted by an influx of fresh, cold water from North America into the Atlantic. However, there are issues with theory an even the person who first suggested it — Wallace Broecker — stated in 2010 that "The long-held scenario that the Younger Dryas was a one-time outlier triggered by a flood of water stored in proglacial Lake Agassiz has fallen from favor due to lack of a clear geomorphic signature at the correct time and place on the landscape". A volcanic event has been proposed and there is more recently and there is evidence of high levels of volcanism in ice cores and cave deposits. immediately before the beginning of the Younger Dryas.

Some have theorized the Younger Dryas was caused by a comet impact. In 2009, after an article appeared in Science, suggesting the hypothesis, the New York Times reported: “ The hypothesis has been regarded skeptically, but its advocates now report perhaps more convincing residue of impact: a thin layer of microscopic diamonds found in rocks across America and in Europe. “We’re up over 30 sites, as far west as offshore California, as far east as Germany,” said Allen West, a retired geology consultant who is one of the scientists working on the research. [Source: New York Times, January 1, 2009]

“The meteors would have been smaller than the six-mile-wide meteor that struck the Yucatán peninsula 65 million years ago and led to the mass extinctions of the dinosaurs. The killing effects of the hypothesized bombardment 12,900 years ago would have been more subtle. Climatologists believe that the direct cause of the 1,300-year cold spell, known as the Younger Dryas, was a sudden rush of fresh water from a giant lake in central Canada to the North Atlantic. Usually a surface current of warm water flows northward in the Atlantic toward Greenland and Europe, then cools and sinks, returning south in the deep ocean. But the fresh water, which is less dense, blocked the sinking of the cold, salty water in the North Atlantic, disrupting the currents. That sudden change in plumbing has long been known, but what caused it has never been satisfactorily explained.

See Did a City-Destroying Meteor Inspire the Sodom and Gomorrah Story? Under SODOM AND GOMORRAH factsanddetails.com

Younger Dryas Period Impact on Humans

There is a lot of archaeological evidence of people all around the globe from the period before and at the beginning of the Younger Dryas period. Afterwards there less evidence of human activity and entire communities — such as the Clovis People along with their advanced tool-making and spearpoints — disappeared.

According to one theory, the Younger Dryas event (c. 10,900 to 9600 B.C.) inspired the development of agriculture. The Younger Dryas produced a sudden drought in the Levant (present-day Israel, Jordan and Lebanon). This could have threatened wild cereals, which were out-competed by dryland scrub. It is presumed that local population had become largely sedentary. To preserve their sedentary way of life they cleared the scrub and planting seeds obtained from elsewhere, originating agriculture. This theory is controversial and hotly debated in the scientific community.

Graham Hancock is a major proponent of Younger Dryas theory, arguing that human hunter-gatherer society as it existed 12,900 years was severely stressed and many people have had a hard time getting enough to eat. According to The Telegraph: the survivors fanned out across the earth to pass on their secrets to our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Hancock believes the Younger Dryas civilisation was the origin of agriculture, architecture, and many of the world’s myths. Its messengers were remembered as gods or giants — Prometheus, Quetzalcoatl. They inspired the legend of Atlantis. And you can still see the monuments their visits inspired, like the Great Sphinx of Giza or the Cuicuilco pyramid in Mexico, which Graham believes are much, much older than the scientific consensus allows. [Source: Sam Kriss, The Telegraph, November 16, 2022]

His lost Ice Age civilisation is advanced, but not too advanced. They might have solved the longitude problem, but they didn’t necessarily have metal tools. “I don't make outrageous claims like microchips or building spaceships or flying to the moon.” He intensely dislikes the people who do make such claims; whenever he talks about them, his usual affability vanishes. “I’m so pissed at the f — ing ancient-aliens lobby. They’ve turned this entire field into a laughing stock.”

Neolithic Revolution Theory

Charles C. Mann wrote in National Geographic, "V. Gordon Childe, an Australian transplant to Britain, was a flamboyant man, a passionate Marxist who wore plus fours and bow ties and larded his public addresses with noodle-headed paeans to Stalinism. He was also one of the most influential archaeologists of the past century. A great synthesist, Childe wove together his colleagues' disconnected facts into overarching intellectual schemes. The most famous of these arose in the 1920s, when he invented the concept of the Neolithic Revolution. [Source:Charles C. Mann, National Geographic, June 2011]

In today's terms, Childe's views could be summed up like this: Homo sapiens burst onto the scene about 200,000 years ago. For most of the millennia that followed, the species changed remarkably little, with humans living as small bands of wandering foragers. Then came the Neolithic Revolution?"a radical change," Childe said, "fraught with revolutionary consequences for the whole species." In a lightning bolt of inspiration, one part of humankind turned its back on foraging and embraced agriculture. The adoption of farming, Childe argued, brought with it further transformations. To tend their fields, people had to stop wandering and move into permanent villages, where they developed new tools and created pottery. The Neolithic Revolution, in his view, was an explosively important event?"the greatest in human history after the mastery of fire."

Civilized Man in Ur in early Mesopotamia

Of all the aspects of the revolution, agriculture was the most important. For thousands of years men and women with stone implements had wandered the landscape, cutting off heads of wild grain and taking them home. Even though these people may have tended and protected their grain patches, the plants they watched over were still wild. Wild wheat and barley, unlike their domesticated versions, shatter when they are ripe — the kernels easily break off the plant and fall to the ground, making them next to impossible to harvest when fully ripe. Genetically speaking, true grain agriculture began only when people planted large new areas with mutated plants that did not shatter at maturity, creating fields of domesticated wheat and barley that, so to speak, waited for farmers to harvest them.

Rather than having to comb through the landscape for food, people could now grow as much as they needed and where they needed it, so they could live together in larger groups. Population soared. "It was only after the revolution — but immediately thereafter — that our species really began to multiply at all fast," Childe wrote. In these suddenly more populous societies, ideas could be more readily exchanged, and rates of technological and social innovation soared. Religion and art — the hallmarks of civilization — flourished.

Childe, like most researchers today, believed that the revolution first occurred in the Fertile Crescent, the arc of land that curves northeast from Gaza into southern Turkey and then sweeps southeast into Iraq. Bounded on the south by the harsh Syrian Desert and on the north by the mountains of Turkey, the crescent is a band of temperate climate between inhospitable extremes. Its eastern terminus is the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in southern Iraq — the site of a realm known as Sumer, which dates back to about 4000 B.C. In Childe's day most researchers agreed that Sumer represented the beginning of civilization. Archaeologist Samuel Noah Kramer summed up that view in the 1950s in his book History Begins at Sumer.

There is a debate among archaeologists as to what caused the Neolithic Revolution. The conventional view for a long time had been that change began taking place about 11,400 years ago when the last ice age came to an end and agriculture became possible, perhaps even necessary for survival. Some archaeologists disagree with this view and believe changes came about as human cognition and psychology changed.

Hunter-Gatherers Versus and Farmers

Gideon Lewis-Kraus wrote in The New Yorker:“The consensus version of the story begins with the appearance of the first anatomically modern humans, about two hundred thousand years ago. For approximately a hundred and ninety thousand years, or about ninety-five per cent of our existence as a species, we lived in small bands of hunter-gatherers, following migratory herds and foraging for wild nuts and berries. These cohorts were small enough, and the demands of resource procurement and allocation were sufficiently minor, that decisions were face-to-face affairs among intimates. Despite the lurking menace of large cats, these early hunter-gatherers didn’t have to work particularly hard to fulfill their caloric needs, and they passed their ample leisure hours cavorting like primates. The order of the day was an easy egalitarianism, mostly for want of other options. [Source: Gideon Lewis-Kraus, The New Yorker, November 8, 2021]

“Twelve thousand years ago, give or take, the static pleasures of this long, undifferentiated epoch gave way to history proper. The hunter-gatherer bands lucky enough to find themselves on the flanks of the Zagros Mountains, or the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, began herding and farming. The rise of agriculture allowed for permanent settlements, which, growing dense, became cities. Urban commerce demanded division of labor, professional specialization, and bureaucratic oversight. Because wheat, unlike wild berries or the hindquarters of an aurochs, was a storable, countable good that appeared on a routine schedule, the selfish administrators of inchoate kingdoms could easily collect taxes, or tributes. Writing, which first emerged in the service of accounting, abetted the sort of control and surveillance upon which primitive racketeers came to depend. Where hunter-gatherers had hunted and gathered only enough to meet the demands of the day, agricultural communities created history’s first surpluses, and the extraction of tributes propped up rent-seeking élites and the managerial pyramids — not to mention standing armies — necessary to maintain their privilege. The rise of the arts, technology, and monumental architecture was the upside of the creation and immiseration of a peasant class.

“From roughly the Enlightenment through the middle of the twentieth century, these developments — which came to be known as the Neolithic Revolution — were seen as generally good things. Societies were categorized by evolutionary stage on the basis of their mode of food production and economic organization, with full-fledged states taken to be the pinnacle of progress.

Did the Neolithic Revolution Bring About Bad Things

Gideon Lewis-Kraus wrote in The New Yorker: It is also possible to think that the Neolithic Revolution was, all in all, a bad thing. In the late nineteen-sixties, ethnographers studying present-day hunter-gatherers in southern Africa argued that their “primitive” ways were not only freer and more egalitarian than the “later” stages of human development but also healthier and more fun. Agriculture required much longer and duller working hours; dense settlements and the proximity of livestock, as well as monotonous diets of cereal staples, encouraged malnutrition and disease. The poisoned fruit of grain cultivation had, in this telling, led to a cycle of population growth and more grain cultivation. Agriculture was a trap. Rousseau’s thought experiment, long written off by conservative critics as romantic nostalgia for the “noble savage,” was resuscitated, in modern, scientific form. It might have taken three or four decades for these insights to make their way to ted stages, but the paleo diet became a fundamental requirement of any self-respecting Silicon Valley founder. [Source: Gideon Lewis-Kraus, The New Yorker, November 8, 2021]

In his book “Sapiens”, Yuval Noah Harari concludes that everything was more or less O.K. until about twelve thousand years ago, when we first beat our swords into plowshares; this innocent decision, which must have seemed a good idea at the time, heralded an era of administrative hierarchy, state-sanctioned violence, and the unchecked proliferation of carbohydrates. Harari takes rather literally Rousseau’s thought experiment that we were born free and rushed headlong into our chains. (“There is no way out of the imagined order,” Harari writes. “When we break down our prison walls and run towards freedom, we are in fact running into the more spacious exercise yard of a bigger prison.”)

Drawing on new archeological findings, and revisiting old ones,David Graeber and David Wengrow, in their book: “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity”, argue that the granaries-to-overlords tale simply isn’t true. Rather, it’s a function of an extremely low-resolution approach to time. Viewed closely, the course of human history resists our favored schemata. Hunter-gatherer communities seem to have experimented with various forms of farming as side projects thousands of years before we have any evidence of cities. Even after urban centers developed, there was nothing like an ineluctable relationship between cities, technology, and domination.

Achievements of Pre-Agricultural People

Gideon Lewis-Kraus wrote in The New Yorker:“Pre-agricultural people erected great testaments to their ways of life in the absence of those structural supports — at Göbekli Tepe, also in Turkey, as well as on the Ukrainian steppe and in the Mississippi Delta. And post-agricultural societies could maintain systematic achievements without administrators to run them. “It turns out that farmers are perfectly capable of co-ordinating very complicated irrigation systems all by themselves,” Graeber and Wengrow say. “Urban populations seem to have a remarkable capacity for self-governance in ways which, while usually not quite ‘egalitarian,’ were likely a good deal more participatory than almost any urban government today.”[Source: Gideon Lewis-Kraus, The New Yorker, November 8, 2021]

Ancient emperors mostly “saw little reason to interfere, as they simply didn’t care very much about how their subjects cleaned the streets or maintained their drainage ditches.” About eight thousand years ago, the villagers of Tell Sabi Abyad, in present-day Syria, saw to a variety of complex tasks — pasturing the flocks; sowing, harvesting, and threshing grain; weaving flax; making beads; and carving stones — that presumably required extensive inter-household coöperation, yet everyone lived in uniform dwellings. Though writing wasn’t invented for another three thousand years, a scheme of geometric tokens, stored and archived in a central if nondescript depot, had been put in place to monitor resource administration. The archeological remains of the village, remarkably preserved by a catastrophic fire that baked its structures of mud and clay, show no signs of caste division or a presiding authority.

“Graeber and Wengrow hope that, once we grasp how ancient mega-sites (in Ukraine or in Jomon-era Japan) could grow large and manifold without a literate bureaucracy, or the way early literate societies (Uruk, in Mesopotamia) might have managed the trick of participatory self-governance, we might renew and expand our own cramped notions of what’s politically tenable. We could come to detach progress from obedience. As they put it, “Humans may not have begun their history in a state of primordial innocence, but they do appear to have begun it with a self-conscious aversion to being told what to do. If this is so, we can at least refine our initial question: the real puzzle is not when chiefs, or even kings and queens, first appeared, but rather when it was no longer possible to simply laugh them out of court.”

“Graeber and Wengrow’s dearest aspiration is to quicken that laughter once again. “Nowadays, most of us find it increasingly difficult even to picture what an alternative economic or social order would be like,” they write. “Our distant ancestors seem, by contrast, to have moved regularly back and forth between them. If something did go terribly wrong in human history — and given the current state of the world, it’s hard to deny something did — then perhaps it began to go wrong precisely when people started losing that freedom to imagine and enact other forms of social existence.”

Natufian Culture (12,500-9500 B.C.)

The Natufian culture refers to most hunter-gatherers who lived in modern-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria approximately 11,500 to 15,000 years ago. They were among the first people to build permanent houses and cultivate edible plants. The advancements they achieved are believed to have been crucial to the development of agriculture during the time periods that followed them.

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica: the Natufian culture os a “Mesolithic culture of Palestine and southern Syria dating from about 9000 B.C.. Mainly hunters, the Natufians supplemented their diet by gathering wild grain; they likely did not cultivate it. They had sickles of flint blades set in straight bone handles for harvesting grain and stone mortars and pestles for grinding it. Some groups lived in caves, others occupied incipient villages. They buried their dead with their personal ornaments in cemeteries. Carved bone and stone artwork have been found. [Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica ]

Europe in the Middle Neolithic Period

A study, published in Nature Scientific Reports by a team of scientists and archeologists from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rechovot and the University of Copenhagen, rejects the long-held “core region” theory that argues that the Natufian culture spread from the Mount Carmel and Galilee region and suggest instead the Natufian’s had far more diverse and complex origins. Daniel K. Eisenbud, Jerusalem Post, December 7, 2017]

Daniel K. Eisenbud wrote in the Jerusalem Post: “According to the researchers, the study is based on evidence from a Natufian site located in Jordan, some 150 km. northeast of Amman. The site, called Shubayqa 1, was excavated by a University of Copenhagen team led by Dr. Tobias Richter from 2012-2015. The excavations uncovered a well-preserved Natufian site, which included, among other findings, a large assemblage of charred plant remains. The botanical remains, which are rare in many Natufian sites in the region, enabled the Weizmann-Copenhagen team to obtain the largest number of dates for any Natufian site yet in either Israel or Jordan.

See Separate Article: NATUFIANS (12,500-9500 B.C.): THE FIRST FARMERS? europe.factsanddetails.com

Natufians and the Debunking of Neolithic Revolution Theory

Charles C. Mann wrote in National Geographic, In the Levant — the area that today encompasses Israel, the Palestinian territories, Lebanon, Jordan, and western Syria — archaeologists had discovered settlements dating as far back as 13,000 B.C. Known as Natufian villages (the name comes from the first of these sites to be found), they sprang up across the Levant as the Ice Age was drawing to a close, ushering in a time when the region's climate became relatively warm and wet. [Source: Charles C. Mann, National Geographic, June 2011]

Although the Natufians lived in permanent settlements of up to several hundred people, they were foragers, not farmers, hunting gazelles and gathering wild rye, barley, and wheat. "It was a big sign that our ideas needed to be revised," says Harvard University archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef.

Natufian villages ran into hard times around 10,800 B.C., when regional temperatures abruptly fell some 12̊F, part of a mini ice age that lasted 1,200 years and created much drier conditions across the Fertile Crescent. With animal habitat and grain patches shrinking, a number of villages suddenly became too populous for the local food supply. Many people once again became wandering foragers, searching the landscape for remaining food sources.

Some settlements tried to adjust to the more arid conditions. The village of Abu Hureyra, in what is now northern Syria, seemingly tried to cultivate local stands of rye, perhaps replanting them. After examining rye grains from the site, Gordon Hillman of University College London and Andrew Moore of the Rochester Institute of Technology argued in 2000 that some were bigger than their wild equivalents — a possible sign of domestication, because cultivation inevitably increases qualities, such as fruit and seed size, that people find valuable. Bar-Yosef and some other researchers came to believe that nearby sites like Mureybet and Tell Qaramel also had had agriculture.

If these archaeologists were correct, these protovillages provided a new explanation of how complex society began. Childe thought that agriculture came first, that it was the innovation that allowed humans to seize the opportunity of a rich new environment to extend their dominion over the natural world...The Natufian sites in the Levant suggested instead that settlement came first and that farming arose later, as a product of crisis. Confronted with a drying, cooling environment and growing populations, humans in the remaining fecund areas thought, as Bar-Yosef puts it, "If we move, these other folks will exploit our resources. The best way for us to survive is to settle down and exploit our own area." Agriculture followed. [Source: Charles C. Mann, National Geographic, June 2011]

Europe in the Late Neolithic Period

The idea that the Neolithic Revolution was driven by climate change resonated during the 1990s, a time when people were increasingly worried about the effects of modern global warming. It was promoted in countless articles and books and ultimately enshrined in Wikipedia. Yet critics charged that the evidence was weak, not least because Abu Hureyra, Mureybet, and many other sites in northern Syria had been flooded by dams before they could be fully excavated. "You had an entire theory on the origins of human culture essentially based on a half a dozen unusually plump seeds," ancient-grain specialist George Willcox of the National Center for Scientific Research, in France, says. "Isn't it more likely that these grains were puffed during charring or that somebody at Abu Hureyra found some unusual-looking wild rye?"

See Separate Article: NATUFIANS (12,500-9500 B.C.): THE FIRST FARMERS? europe.factsanddetails.com

Between the Natufians (12,500-9500 B.C.) and Halaf Period (6500–5500 B.C.)

The Khiamian Period (c. 10,200 – c. 8,800 B.C., also referred to as El Khiam or El-Khiam) is a period of the Near-Eastern Neolithic, marking the transition between the Natufian and the Pre-Pottery Neolithic. Some sources date it from about 10,000 to 9,500 B.C., The Khiamian is named after the site of El Khiam, situated on banks of the Dead Sea, where researchers have recovered the oldest chert arrows heads, with lateral notchs, the so-called "El Khiam points", which has served to identify sites in Israel, (Azraq), Sinai (Abu Madi), and to the north as far as the Middle Euphrates (Mureybet). [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Khiamian is regared as a time without any major technical innovations. However, for the first time houses were built on the ground level, not half buried as was previously done. Otherwise, members of this culture were still hunter-gatherers. Agriculture was still rather primitive. Relatively new discoveries in the Middle East and Anatolia show that some experiments with agriculture had taken place by 10,900 B.C. and wild grain processing had occurred by 19,000 B.C. at Ohalo II. According to Jacques Cauvin, the Khiamian was the beginning of the worship of the Woman and the Bull, found in later following periods in the Near-East, based on the appearance of small female statuettes, as well as by the burying of aurochs skulls.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN, around 8500-5500 B.C.) is the name of the early Neolithic Period in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent. The domestication of plants and animals was evolving at this time, possibly triggered by the Younger Dryas drought around 11,000 years ago. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture came to an end around the time of the 8.2 kiloyear event, a cool spell that lasted several hundred years and peaked around on 6200 B.C.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN, around 8500-5500 B.C.) Period is divided into three periods 1) Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA 8500 B.C. - 7600 B.C.); 2) Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB 7600 B.C. - 6000 B.C.) and 3) Pre-Pottery Neolithic C culture (culture continued a few more centuries at 'Ain Ghazal in Jordan).

Around 8000 B.C. during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) the world's first town Jericho appeared in the Levant. PPNB differed from PPNA in showing greater use of domesticated animals, a different set of tools, and new architectural styles.

Halaf and Ubaid Periods (6500–4000 B.C.) and the Origins of Irrigation

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In the period 6500–5500 B.C., a farming society emerged in northern Mesopotamia and Syria which shared a common culture and produced pottery that is among the finest ever made in the Near East. This culture is known as Halaf, after the site of Tell Halaf in northeastern Syria where it was first identified. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Halaf Period (6500–5500 B.C.)", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“In the period 5500–4000 B.C., much of Mesopotamia shared a common culture, called Ubaid after the site where evidence for it was first found. Characterized by a distinctive type of pottery, this culture originated on the flat alluvial plains of southern Mesopotamia (ancient Iraq) around 6200 B.C. Indeed, it was during this period that the first identifiable villages developed in the region, where people farmed the land using irrigation and fished the rivers and sea (Persian Gulf). Thick layers of alluvial silt deposited every spring by the flooding rivers cover many of these sites. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Ubaid Period (5500–4000 B.C.)", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Some villages began to develop into towns and became focused on monumental buildings, such as at Eridu and Uruk. The Ubaid culture spread north across Mesopotamia, gradually replacing the Halaf culture. Ubaid pottery is also found to the south, along the west coast of the Persian Gulf, perhaps transported there by fishing expeditions. \^/

The Samarra culture is a Copper Age culture in northern Mesopotamia that existed roughly dated from 5500 to 4800 B.C.. Partially overlaping with the Hassuna and early Ubaid periods, . Samarra its is associated most with the sites of of Samarra, Tell Shemshara, Tell es-Sawwan and Yarim Tepe. At Tell es-Sawwan, evidence of irrigation—including flax—establishes the presence of a prosperous settled culture with a highly organized social structure. The culture is primarily known for its finely made pottery decorated with stylized animals, including birds, and geometric designs on dark backgrounds. This widely exported type of pottery, one of the first widespread, relatively uniform pottery styles in the Ancient Near East, was first recognized at Samarra. The Samarran Culture was the precursor to the Mesopotamian culture of the Ubaid period.

Choga Mami a Samarran site in Diyala Province, Iraq about 110 kilometers northeast of Baghdad, shows some of world’s earliest evidence of irrigation. The first canal irrigation operation dates to about 6000 B.C.. The site,, has been dated to the late 6th millennium B.C., was occupied in several phases from the Samarran culture through the Ubaid. Buildings were rectangular and built of mud brick, including a guard tower at the settlement's entrance. Irrigation supported livestock (cattle, sheep and goats) and arable (wheat, barley and flax) agriculture. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: EARLY HISTORY OF MESOPOTAMIA: BEFORE SUMER africame.factsanddetails.com

What Caused Human Societies to Develop

Gideon Lewis-Kraus wrote in The New Yorker:“If cities didn’t lead to states, what did? Not any singular arrow of history, according to Graeber and Wengrow, but, rather, the gradual and dismal coalescence of otherwise unrelated, parallel processes. In particular, they think it involved the extension of patriarchal domination from the home to society at large. Their account of how household structures were transformed into despotic regimes requires some unconvincing hand-waving, but throughout they emphasize that any given process can be historically contingent without being simply inexplicable. The guiding principle of “The Dawn of Everything” is that our remote ancestors — not to mention certain present-day Indigenous groups long dismissed as living relics of superannuated barbarians — must be viewed as self-conscious political actors. Historical ruptures cannot be reduced to technological novelties or geographical constraints, even if those factors played crucial roles. They arose from our own choices and actions. [Source: Gideon Lewis-Kraus, The New Yorker, November 8, 2021]

“Graeber and Wengrow point to moments in the distant past in which they see instances of deliberate refusal: communities that weighed the advantages and disadvantages of one ostensibly evolutionary step or another (pastoralism, royal domination) and decided that they liked their current odds just fine. The communities that built Stonehenge had once adopted ways of cultivating cereal from Continental Europe, but recent research suggests that they returned to hazelnut collection around 3300 B.C. Various ecological theories have been floated to explain the sudden collapse, around 1350 A.D., of the brutal dynasty of Cahokia (in present-day Illinois), then the largest city in the Americas north of Mexico, but Graeber and Wengrow propose that the proto-empire’s subjects — who lived under constant surveillance and the threat of mass executions — simply defected en masse. Land wasn’t scarce, and they just walked away.

“Where some groups adopted and abandoned different arrangements over time, others maintained a repertoire of assorted practices to suit fluctuating purposes. Modern ethnographic treatments of Indigenous communities describe an astonishing level of social plasticity (available to us, perhaps, in the highly etiolated form of Burning Man and other “temporary autonomous zones”). In a 1903 essay, the anthropologists Marcel Mauss and Henri Beuchat described the routine organizational reversals in Inuit communities. These groups spent their summers fishing and hunting in small cohorts under the possessive — and coercive — authority of a single male elder. Graeber and Wengrow describe how then, as the winter brought an influx of walruses and seals to the shore, “the Inuit gathered together to build great meeting houses of wood, whale rib and stone,” where “virtues of equality, altruism and collective life prevailed. Wealth was shared, and husbands and wives exchanged partners.” It’s impossible to say whether such practices were designed or preserved to diminish the threat of permanent domination, but that was one of their effects.

Image Sources: Wikipedia Commons, except Paleolithic map from Palomar College

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024