FIRST CERAMIC FIGURINES

Venus of Dolni Vestonice Some of earliest known ceramics were found at Dolni Vestonice and Pavlove, hill sites in the Czech Republic that were the home of prehistoric seasonal camps. Thousands of fragments of human figures, as well as the kilns that produced them have been found in sites in Moravia in what is now Russia the Czech Republic. Some have been dated to be 26,000 years old. The figurines were made from moistened loess, a fine sediment, and fired at high temperatures. Predating the first known ceramic vessels by 10,000 years, the figurines, some scientists believe, were produced and exploded on purpose based on the fact that most of the sculptures have been found in pieces.

Some of the sculpture may represent the first example of portraiture (representation of an actual person). One such figure, carved in mammoth ivory, is roughly three inches high. The subject appears to be a young man with heavy bone structure, thick, long hair reaching past his shoulders, and possibly the traces of a beard. Particle spectrometry analysis dated it to be around 29,000 years old. [Source: Wikipedia]

The remains of a kiln was found on an encampment in a small, dry-hut, whose door faced towards the east. Scattered around the oven were many fragments of fired clay. Remains of clay animals, some stabbed as if hunted, and other pieces of blackened pottery still bear the fingerprints of the potter.

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Jomon Potteries in Idojiri Vol.1 B/W Edition: Tounai Ruins by Idojiri Archaeological Museum, Norio Yokogoshi, et al. (2015) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Japanese Arts: Jomon Pottery” (1968) by J Edward Kidder Amazon.com;

“Jomon Of Japan: The World's Oldest Pottery” by Douglas Moore Kenrick (1995) Amazon.com;

“Power of Dogu: Ceramic Figures from Ancient Japan” by Simon Kaner Amazon.com;

“Jomon Reflections: Forager Life and Culture in the Prehistoric Japanese Archipelago” (2003)

by Simon Kaner (Author), Tatsuo Kobayashi Amazon.com;

“Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilisation in China, Korea and Japan”

by Gina L. Barnes Amazon.com;

“Ancient Gold: The Wealth of the Thracians” by Ivan Marazov (1998) Amazon.com;

“Gold of the Thracian horsemen: Treasures from Bulgaria : Montréal, Palais de la civilisation” (1987) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Thrace and the Classical World: Treasures from Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece”

by Jeffrey Spier, Timothy Potts, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Ancient Thrace” by Julia Valeva, Emil Nankov. Denver Graninger (2020) Amazon.com;

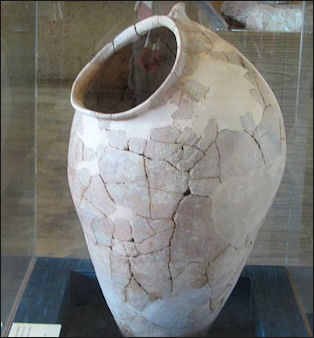

Early Pottery

The making of ceramic and clay vessels is both an important utilitarian craft and one of the oldest human arts. Earthenware pottery (pots made by firing clay in a kiln) was first developed in the Near East around 7000 B.C. Early pottery vessels were used primarily for storing liquids, grains and other items. Clay pots were used for cooking and storage. Nine thousand year old sites in Turkey with ancient pottery have yielded mostly bowls and cups. The Near East, the region between the eastern shores of the Mediterranean to present-day Afghanistan, was rich in clays, metal ores and iron-rich pigments. These allowed some of the earliest metalworking and pottery-making developments.

Potters first fired vessels in hearths, and afterwards in kilns. Kilns are special structures made of bricks or stones in which temperatures of at least 1,050̊C can be generated. Firing ceramics at high temperatures improves their durability and impermeability and creates greater opportunities for changing the surface color.

Early Pottery Making

The first pottery vessels were fashioned by hand from lumps of clay. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. With a potter’s wheel, the a lump of clay is spun around and round, shaped, usually into a vessel, with the hands and a variety of tools.

To make a pottery vessel, a potter must find the right clay, and purify and cure it to make it usable. Raw clays have traditionally been put into large vats to remove foreign matter such as sand and pebbles. When clay is washed these materials settle to the bottom while the clay remains suspended and is poured off. Clay washed in this manner is known as slip.

Common ways of decorating pottery included printing selected areas, covering the surfaces with a thin slip made of iron-rich red clay, and burnishing (compacting the surface with a hard, tool such as a pebble).

World's First Pottery from Japan?

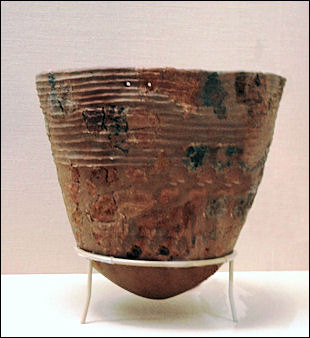

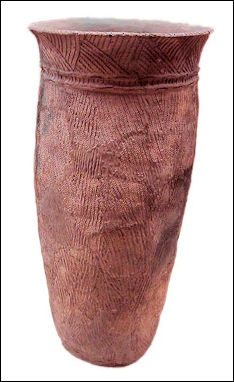

Jomon pottery from Japan has been dated to around 16,000 years ago (14,000 B.C.) and is regarded as the oldest in the world although of similar ages have been found in southern China, the Russian Far East, and Korea. Pottery is made by cooking soft clay at high temperatures until it hardens into an entirely new substance — ceramics. Some Jomon pottery was decorated with markings made by pressing various items including lengths of cord into the wet clay before firing. Pottery from Japan preceded ceramics from Mesopotamia by over two thousand years. Ancient pottery with similar styling and dates have been found in China and the Russian Far East. China now claims it is the home of the world's oldest pottery (See Below).

10,000-year-old Jomon pottery The earliest pieces of Jomon pottery were small rounded pots were plain or had bean, linear or fingernail applique decorations. Later cord-marked decorations appeared, from which the name “Jomon” (meaning “chord-marked”) is derived. Excavations have revealed pottery fragments from very small, rounded pots made by a hunter-gathering people living in the Kanto plain, where Tokyo is now located, that may be 16,000 years old. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

In 1998 small fragments were found at the Odai Yamamoto I site, which have been dated to the 14th millennium BC; subsequently, pottery of the same age was found at other sites such as Kamikuroiwa in Shikoku and Fukui Cave in northwestern Kyushu. Archaeologist Junko Habu claims that "The majority of Japanese scholars believed, and still believe, that pottery production was first invented in mainland Asia and subsequently introduced into the Japanese archipelago." However, at present it appears that pottery emerged at roughly the same time in Japan, the Amur River basin of far eastern Russia, and China. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Some early Jomon pottery is characterized by the cord-marking that gives the period its name and has now been found in large numbers of sites. The pottery of the period has been classified by archaeologists into some 70 styles, with many more local varieties of the styles. The antiquity of Jomon pottery was first identified after World War II, through radiocarbon dating methods. The earliest vessels were mostly smallish round-bottomed bowls 10–50 cm high that are assumed to have been used for boiling food and, perhaps, storing it beforehand. They belonged to hunter-gatherers and the size of the vessels may have been limited by a need for portability. As later bowls increase in size, this is taken to be a sign of an increasingly settled pattern of living. These types continued to develop, with increasingly elaborate patterns of decoration, undulating rims, and flat bottoms so that they could stand on a surface. +

Jomon Pottery from Japan

Hundreds of thousands of pieces of Jomon pottery have been found at archaeological excavation and building construction sites. Such massive amounts of pottery implies that the Jomon people engaged in the craft on an almost industrial scale and were more than simple hunters and gatherers.

Jomon Period rope

pottery from 5000 to 4000 BC Charles T. Keally wrote: “It is commonly thought that the oldest pottery in Japan is the linear-relief potsherds from the Fukui Cave site in northwestern Kyushu, dated about 10,000-10,500 B.C. In fact there are several sites, scattered all over the country except in Okinawa in the far south, that have yielded potsherds from strata dated around 11,000 B.C. — in Hokkaido in the far north (Higashi Rokugo 2); in Aomori at the northern end of the main island of Honshu (Odai Yamamoto I); in Ibaragi (Ushirono), Tokyo (Maeda Kochi) and Kanagawa (Kamino) in east-central Honshu; and in Nagasaki (Sempukuji) in northwestern Kyushu in western Japan. The ages of these sites rival anything on the continent. But more significant is the fact that pottery becomes common in Japanese sites from around 7500-8000 B.C., except in Hokkaido and Okinawa, and that is not true of continental sites. [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, t-net.ne.jp/~keally/jomon. ++]

The manufacture of pottery typically implies some form of sedentary life because pottery is heavy, bulky, and fragile and thus generally unusable for hunter-gatherers. However, this does not seem to have been the case with the first Jomon people, who perhaps numbered 20,000 over the whole archipelago. It seems that food sources were so abundant in the natural environment of the Japanese islands that it could support fairly large, semi-sedentary populations. The Jomon people used chipped stone tools, ground stone tools, traps, and bows, and were evidently skillful coastal and deep-water fishermen. [Source: Wikipedia]

Aileen Kawagoe wrote in Heritage of Japan: “Pottery was one of the most useful crafts for the Jomon, and this can be seen from the large numbers of pots and other clay vessels that they produced. Jomon women are thought to have produced pottery for household daily uses such as cooking and storage, but also for decoration and for special ceremonies. If you've ever tried to move a heavy terracotta flowerpot, you'll know that it's no fun lugging one of these around…especially on foot. The fact that the Jomon people made so many pots tells us one important thing, these hunter-gathering people couldn't have been wandering around all the time (i.e., they couldn't have been nomadic) and must have settled down somewhere at least for part of the year (they were sedentary or semi-sedentary)...From excavated finds, scholars believe that the earliest pottery in Japan was produced by riverside hunter fishers who had microlithic blade technology. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

20,000-Years-Old Pottery Found in a Chinese Cave

In June 2012, AP reported: “Pottery fragments found in a south China cave have been confirmed to be 20,000 years old, making them the oldest known pottery in the world, archaeologists say. The findings, which will appear in the journal Science, add to recent efforts that have dated pottery piles in east Asia to more than 15,000 years ago, refuting conventional theories that the invention of pottery correlates to the period about 10,000 years ago when humans moved from being hunter-gathers to farmers. [Source: Didi Tang, Associated Press, June 28, 2012]

“The research by a team of Chinese and American scientists also pushes the emergence of pottery back to the last ice age, which might provide new explanations for the creation of pottery, said Gideon Shelach, chair of the Louis Frieberg Center for East Asian Studies at The Hebrew University in Israel. "The focus of research has to change," Shelach, who is not involved in the research project in China, said by telephone. In an accompanying Science article, Shelach wrote that such research efforts "are fundamental for a better understanding of socio-economic change (25,000 to 19,000 years ago) and the development that led to the emergency of sedentary agricultural societies." He said the disconnection between pottery and agriculture as shown in east Asia might shed light on specifics of human development in the region.

Xianrendong cave pottery

“Wu Xiaohong, professor of archaeology and museology at Peking University and the lead author of the Science article that details the radiocarbon dating efforts, told The Associated Press that her team was eager to build on the research. "We are very excited about the findings. The paper is the result of efforts done by generations of scholars," Wu said. "Now we can explore why there was pottery in that particular time, what were the uses of the vessels, and what role they played in the survival of human beings."

“The ancient fragments were discovered in the Xianrendong cave in south China's Jiangxi province, which was excavated in the 1960s and again in the 1990s, according to the journal article. Wu, a chemist by training, said some researchers had estimated that the pieces could be 20,000 years old, but that there were doubts. "We thought it would be impossible because the conventional theory was that pottery was invented after the transition to agriculture that allowed for human settlement." But by 2009, the team — which includes experts from Harvard and Boston universities — was able to calculate the age of the pottery fragments with such precision that the scientists were comfortable with their findings, Wu said. "The key was to ensure the samples we used to date were indeed from the same period of the pottery fragments," she said. That became possible when the team was able to determine the sediments in the cave were accumulated gradually without disruption that might have altered the time sequence, she said.

“Scientists took samples, such as bones and charcoal, from above and below the ancient fragments in the dating process, Wu said. "This way, we can determine with precision the age of the fragments, and our results can be recognized by peers," Wu said. Shelach said he found the process done by Wu's team to be meticulous and that the cave had been well protected throughout the research.

The same team in 2009 published an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, in which they determined the pottery fragments found in south China's Hunan province to be 18,000 years old, Wu said. "The difference of 2,000 years might not be significant in itself, but we always like to trace everything to its earliest possible time," Wu said. "The age and location of pottery fragments help us set up a framework to understand the dissemination of the artifacts and the development of human civilization."

Very Old Pottery from the Russian Far East

Very old pottery has been found in Amur River basin of the Russian Far East that appears to be as old as that found in Japan. The oldest Russian Far East ceramics are accompanied by stone artifacts made in the blade technique characteristic of the late Paleolith era or Neolithic era. In an article entitled “On Early Pottery-Making in the Russian Far East," Irina Zhushchikhovskaya wrote: “Sites containing simple ceramics were discovered in the Amur River basin, the Primorie (Maritime) region, and on Sakhalin Island. These sites are widely dated from between 13,000 to 6000” before present (B.P.) “In the Russian Far East, the problem of pottery-making origins has been explored only recently."Source:“On Early Pottery-Making in the Russian Far East” by Irina Zhushchikhovskaya, Asian Perspectives, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Fall 1997), pp. 159-174, University of Hawai'i Press ==]

“Early ceramics assemblages from various regions in the northern part of the Sea of Japan basin and the Russian Far East are characterized by certain technological and morphological features. Two types of ceramic pastes can be distinguished, the first employing natural clay without artificial temper (Ustinovka-3, Almazinka) and the second using clay with plant fiber artificial temper (Gasya, Khummy, Yuzhno-Sakhalinskaya culture, Chernigovka-1). Not all of the pottery assemblages provide evidence of forming techniques.At least three can be identified: a moulding technique, perhaps in conjunction with the use of a paddle and anvil, slab construction and coiling. These features are similar to those described for early ceramics from otherregions of eastern Asia and elsewhere in the world. For example, a ceramic paste of untempered natural clay is typical for the earliest pottery of Japan (Vandiver 1991). ==

Xianrendong cave

“The early ceramic assemblages of the Russian Far East share many technological and morphological properties with early ceramics discovered in other regions of the world. This resemblance may be explained, in part, by the comparable level of pottery-making development that restricted the technological and morphological choice. Variability within these early ceramic traditions developed gradually, as skills and expertise improved. At the same time, it may be noted that regional differences appeared in the very earliest stages of pottery-making. Ceramic assemblages from the Russian Far East show evidence of partial moulds and possibly paddle and anvil techniques. In early Jomon assemblages, slab construction was employed, followed by coiling in later assemblages. ==

“The Russian Far Eastern early ceramic assemblages that represent a common pottery-making level are placed into a fairly wide temporal interval between 13,000 and 6000 B.P. This large interval may reflect the few radiocarbon dates yet available for these assemblages and the lack of other absolute dating methods. This article has shown that sites associated with early ceramics within each of the regions included here are consistently dated to a somewhat narrower interval of time. The lower Amur River basin is characterized by the oldest dates of the sites, ranging from 13,000 to 10,000 B.P. The sites from Primorie region occupy an intermediate position, between 8500 and 7500 B.P., and Sakhalin Island is characterized by the most recent sites, dated to 6500-6000 B.P. This chronological sequence possibly reflects the geographically uneven dynamics for the introduction of pottery-making in the territories of the Russian Far East. ==

“The lower Amur River basin may be interpreted as a region of the earliest ceramics. Radiocarbon dates for the lowest components of the Gasya and Khummy sites are close to the dates of the Jomon sites in Japan containing the most unadvanced pottery. The ages of the sites in the Primorie region associated with early ceramics tend to match dates for sites associated with early pottery from areas to the south and southeast in China (Jiao 1995; Wang Xiao Qing, 1995). ==

Comparing Very Old Pottery from the Russian Far East with Jomon Pottery

In “On Early Pottery-Making in the Russian Far East," Irina Zhushchikhovskaya wrote: My inspection of Incipient Jomon ceramics from Kiriyama-Wada and Jin located in Honsu and dated to approximately 12,000-10,000 B.P. suggests some trends involving the technology of paste among these early ceramics. The ceramics from the earliest sites (or components of sites) have a paste prepared of rough, unworked natural clay. The ceramics from later components is characterized by clay in which more of the large particles have been removed, producing a more plastic clay paste that is still untempered. [Source:“On Early Pottery-Making in the Russian Far East” by Irina Zhushchikhovskaya, Asian Perspectives, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Fall 1997), pp. 159-174, University of Hawai'i Press ==]

ossuary in the shape of a silo

“Plant fiber-tempering technologyoccurred in the pottery of the Initial and Earliest Jomon periods (Nishida 1987). This technology appeared in the early ceramics of North and Central America (Griffin 1965; Hoopes 1994; Reichel-Dolmatoff 1971; Reid 1984), Near East and Central Asia (Amiran 1965; Saiko 1982), and now for the materials from the Russian Far East. There is some evidence for the use of mould forming methods in ceramic assemblages from south and southeast China dated to 10,000-9000 B.P. (Wang Xiao Qing 1995). The use of moulds in the forming process was popular in several areas of Eurasia (Bobrinsky 1978). ==

“According to P. B. Vandiver, the earliest Japanese pottery was formed by a method similar to slab construction. Coiling was not employed in the initial stage of pottery production (Vandiver 1991). The combination of partial moulding and slab construction took place in some cases (Vandiver 1987). Similar examples of this technique were discovered in sites from south China dated between 9000 and 8000 B.P. A roundish stone or a basket may have been used as a mould to which pieces of clay were then applied (Wang Xiao Qing 1995). The coiling method for making pottery is widely represented amongarchaeological assemblages throughout the world. Obvious evidence for this method can be identified among later ceramics from Jomon sites in Japan. ==

“A relatively simple morphological pattern was a common characteristic of early ceramics. Nonetheless, vessels with a rectangular shape also occurred in early pottery-making. The box-shaped vessels associated with Sakhalin Island's Yuzhno-Sakhalinskaya culture are similar to those from sites in northern Japan dated to 13,000-10,000 B.P. (Suda 1995). ==

“A common trait of both the Russian Far Eastern and Japanese sites is the occurrence of early ceramics together with a lithic industry combining elements from the Late Paleolithic and Neolithic. This may reflect certain technical and social contexts linked to the first appearance of pottery in this part of the world. Because the first discoveries of early ceramics in East Asia occurred in theJapanese archipelago, initial conceptions about the origins of pottery-making emphasized this territory (Ikawa-Smith 1976; Serizawa 1976). The discovery of the new sites containing early ceramics in the Russian Far East indicates that the area of ceramic origins needs to be broadened to include the Sea of Japan basin as a whole (Zhushchikhovskaya 1995b). Clearly, this perspective will lead to more comparative and new field research on the origins of pottery-making." On Sakhalin Island however, the dates are more recent: “The most archaic pottery-making tradition in this region is connected with the sites of the Yuzhno-Sakhalinskaya archaeological culture (Golubev and Zhushchikhovskaya 1987). It is radiocarbon dated to approximately 6500-6000 B.P. The location of this archaeological culture is the southern portion of Sakhalin Island (Shubin et al. 1984)." ==

Ancient Metal Working

The Near East was rich in clays, metal ores and iron-rich pigments. These allowed some of the earliest metalworking and pottery-making developments. By 3500 B.C., in the Near east, metalworkers had developed a method of extracting metal from its ores. Copper, silver, lead and gold were all worked. Varna on the Danube had a thriving metal industry in 4000 B.C.

Because of the uneven availability of ore sources and the sophistication of the technology it helped some cultures gain an upper hand over others. It also meant that metal objects became greatly desired as works of art and metal for weapons

See Copper Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age

Cinnabar (Red Mercury) in Neolithic Times

Cinnabar on dolomite

Aileen Kawagoe wrote in Heritage of Japan: “Cinnabar refers to a common bright scarlet to brick-red form of mercury sulfide. The most common source ore for refining elemental mercury, it is a very toxic and in ancient times was used to make brilliant red or scarlet pigments. The word ‘cinnabar’ comes from the Persian word for ‘dragon’s blood’ and it is still ‘harvested’ and used for both practical and metaphysical purposes. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

“The earliest use of the cinnabar mineral is from the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük in Turkey (7000-8000 B.C.) where wall paintings included cinnabar’s vermillion. “The primary prehistoric use of the mineral was grinding it to create vermillion”, according to Cinnabar: History of Mercury Mineral Use. The article also puts the use of cinnabar as a pigment beginnning ~5300 B.C. Lead isotope analysis identified the provenance of these cinnabar pigments as coming from the Almaden district deposits[Iberian peninsula]. (see Consuegra et al. 2011).

“Also important locations, according to the above article, on the early cinnabar trail are: “The Neolithic Vinca culture (4800-3500 B.C.), located in the Balkans and including the Serbian sites of Plocnik, Belo Brdo, and Bubanj, among others, were early users of cinnabar, likely mined from the Suplja Stena mine on Mount Avala, 20 kilometers (12.5 miles) from Vinca. Cinnabar occurs in this mine in quartz veins; Neolithic quarrying activities are attested here by the presence of stone tools and ceramic vessels near ancient mine shafts.

Catherine’s Blog About Jewelry, Gemstones reported: “Theophrastus (372 BC- 288 B.C.), a Greek naturalist, mentions the use of cinnabar as early as the 6th century B.C. But early Chinese objects show traces as far back as the second millenium B.C. The Romans mined cinnabar ores for mercury near the Gulf of Trieste and in Almaden, Spain (home of the largest mercury mine in the world). Several of these mercury mines are still in use today, 2500 years later. According to Rome’s famous engineer, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (90-20 B.C.), miners of cinnabar ore quickly showed poisonous effects: tremors, extreme mood changes and loss of hearing progressing to severe mental derangement and death. The Romans solved the problem of toxicity by turning the cinnabar mines into penal institutions for criminals, slaves and other undesirables….

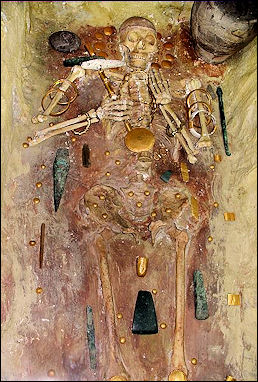

World’s Oldest Gold Artifacts, from Bulgaria

Bulgarian gold from Varna, 4600-4200 BC

The world's oldest known gold artifacts, a couple of 6000-year-old goat figures with holes punched in them, were not found in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley or Egypt, they were discovered in 1972 in a grave by a tractor operator laying some electric cable in northeastern Bulgaria. [Source: Colin Renfrew, National Geographic, July 1980]

The largest golden goat was about two-and-a-inches long. It was discovered along with about 2,000 other gold pieces (weighing more that 12 pounds) in 250 excavated graves in an ancient cemetery near the Black Sea town of Varna. The pieces included golden necklaces, breastplates, chains, bracelets, earrings, a hammer, and a bowl painted in gold.

The find was shocking. Most cultures still used stone tools in this period, a few had developed copper axes and awls, and the development was bronze was a thousand years away, and iron two thousand years. The gold pieces date back to at least 4000 B.C., and they may go as far back as 4600 B.C.

Tiny Bead from Bulgaria May Be World's Oldest Gold Artifact

In 2016, archaeologists announced that a 15-centigram gold bead found near the village of Yunatsite in southern Bulgaria may be the world’s oldest gold artifact. Angel Krasimirov of Reuters wrote: “It may be just a tiny gold bead — 4 mm (1/8 inch) in diameter — but it is an enormous discovery for Bulgarian archaeologists who say they have found Europe's - and probably the world's - oldest gold artifact. The bead, found at a pre-historic settlement in southern Bulgaria, dates back to 4,500-4,600 B.C., the archaeologists say, making it some 200 years older than jewelry from a Copper Age necropolis in the Bulgarian Black Sea city of Varna, the oldest processed gold previously unearthed, in 1972. "I have no doubt that it is older than the Varna gold," Yavor Boyadzhiev, associated professor at the Bulgarian Academy of Science, said. "It's a really important discovery. It is a tiny piece of gold but big enough to find its place in history." [Source: Angel Krasimirov, Reuters, August 10, 2016]

Bulgarian gold bull from Varna, 4600-4200 BC

“Boyadzhiev, believes the bead was made at the site, just outside the modern town of Pazardzhik, which he says was the first "urban" settlement in Europe, peopled by "a highly-cultured society" which moved there from Anatolia, in today's Turkey, around 6,000 B.C. "I would say it is a prototype of a modern town, though we can say what we have here is an ancient town, judged by Mesopotamian standards," Boyadzhiev said. "But we are talking about a place which preceded Sumer by more than 1,000 years," he added, referring to what is usually considered the first urban civilization, based in southern Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq.

“The gold bead, weighing 15 centigrams (0.005 ounce), was dug up two weeks ago in the remains of a small house that would have stood at a time when metals such as copper and gold were being used for a first time. The settlement unearthed so far is between 10 and 12 hectares (25-30 acres) and would have had a 2.8-metre-high (9-foot) fortress wall. Anything over 0.7-0.8 hectares is regarded as a town by researchers working in Mesopotamia, Boyadzhiev said. More than 150 ceramic figures of birds have been found at the site, indicating the animal was probably worshipped by the town's people. The settlement was destroyed by hostile tribes who invaded from the north-east around 4,100 B.C. The bead will be exhibited in the historical museum in Pazardzhik once it has been thoroughly analyzed and its age confirmed, a museum worker said.”

3,800-Year-Old Golden Cup Found in Italy

In 2012, archaeologists have dated a rare golden cup uearthed near the town of Montecchio Emilia in Northern Italy to about 1800 B.C., making it one of only three other similar golden cups discovered in Europe and Britain. According to Popular Archaeology: “The cup turned up during a survey of a gravel pit located along terraces adjacent to the Enza River. Previous surveys in nearby areas also revealed evidence of dwellings of the late-Neolithic and Bronze Ages (IV-III millennium B.C), terramara cremation urns from the mid-recent Bronze Age (XIV-XII centuries B.C.), and Etruscan graves. [Source: Popular Archaeology, October26, 2012 ||~||]

Gold from Varna necropilis “A recent report stated that “It had clearly been lifted up and partially moved by the plough quite some time ago. No structure, tomb or anything else that could be correlated to the original resting place of the cup was found: evidently, it must have been buried in a simple hole in the bare earth. It appears to have been smashed in ancient times, then later partially broken by a plough, which seems to have pulled out a small piece”. ||~||

“Archaeologists suggest that it might have served as a ritual cup, but the difficulty of its context when found has left archaeologists puzzled about the use, meaning and owners of the vessel. As reported, “No other elements – from strictly the same period as the Montecchio cup – were found in the gravel pit area: it thus must have been hidden away or placed there as a votive offering, although some information from the archives, presently under examination, might be able to link the cup to a finding of 13 gold objects, apparently from the Bronze Age, when a field in Montecchio was ploughed on January 18, 1782: unfortunately, the items were melted down. All that remains are lively descriptions from the period”. ||~||

Regarding the three other similar cups found in previous investigations, one was discovered in Fritzdorf, Germany in 1954 and is currently exhibited at the Landesmuseum in Bonn, Germany. The other two are exhibited at the British Museum and were found, respectively, in Rillaton (Cornwall) and Ringlemore (Kent) in the U.K. The U.K. cups differed from the Italian and German cups in that they featured a corrugated external surface. It is thought that there could be a trade system relationship that links the cups. According to Dr. Filippo Maria Gambari, Superintendent of the Archaeological Heritage of Emilia Romagna, “this find ideally links this area of Italy with the henges of the United Kingdom and the area of North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany)”. ||~||

“Scientists studying the vessel found in Italy hope that further testing and analysis will provide clues relating to the origin, purpose, and makers, including its possible relationship to the other cups and the trade relationships and systems that existed at the time of its manufacture. Says Gambari, “this research could change the well-established ideas of trade in Bronze Age Europe”.” ||~||

World's First Money

The worlds' first money, many scholars say, was circulated in the 7th century B.C. by the Lydians.. The thumb-nail-size coins were struck from lumps of electrum, a pale yellow alloy of gold and silver, that had washed down streams from nearby limestone mountains. The late Oxford scholar Colin Kray surmised that the Lydian government found the coins useful as standard medium of exchange and merchants liked them because they didn't have to do a lot of weighing and measuring. [Source: Peter White, National Geographic, January 1993]

Lydian gold coin of Croesus There is some debate as to where the world's first money came from. Some scholars say the world's oldest coins are spade money from Zhou dynasty China dated to 770 B.C. In the seventh century B.C. coins were minted in China with the names of towns printed on them. These coins were tiny, minted pieces of bronze shaped like knives and spades.

The Lydians lived on the west coast of Asia Minor near present-day Izmir, Turkey, They made thumb-nail-size coins under King Gyges in 670 B.C. What made the Lydian coins different from the Chinese coins were inscriptions of the king’s government — widely seen as endorsement of the money by the king. Some coins had portraits of Lydian King Gyges. These have been found as far east as Sicily. Others were struck in denominations as small as .006 of an ounce (1/50th the weight of a penny).

Electrum was panned from local riverbeds. First unearthed at the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the coins had many of the same features of modern coins: they were made of a precious metal, the were a specific measured size and they were stamped with images of rulers, animals and mythical beats.

The idea of coinage was so popular that it was adopted by several Greek city-states only a few decades after the first coins appeared in Lydia. The Greeks made coins of various denominations in unalloyed gold and silver and the stamped them with images of gods and goddesses.

Lydian Gold

The Lydians also likely produced the first pure gold and pure silver coins during the kingdom of Croesus (561-547 B.C.) The problem with the electrum coins is that the amount of gold varied and thus the value of the coins varied.. This problem was solved by producing pure or nearly pure gold and silver coins. The Lydians developed an innovative refining process for retrieving gold from the ore taken from the Pactolus River, which had a high copper and silver content: 1) they pounded the metal to increase its surface area. 2) Base metals like copper were removed through cupellation, melting lead with the metal, subject into bursts of hot air from bellows. The heat separates the gold and silver alloy from the molten mass of lead oxide that absorbed the copper. 3) hammered pieces of gold, with silver in the, were damped and mixed with salt and placed in a small earthenware container. 4) The container is heated at a high temperature for several days. The salt, moisture and earthenware surface react producing a corrosive vapor that penetrates the metal and removed the silver. 5) the pieces of pure gold are removed, melted and forged.

Lydian coin

Archeologist found a vase full of gold coins. But otherwise few gold items have been found at Lydian sites. Maybe the stiff was taken by Persians or other conquerors.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018