WAR AND EARLY MODERN HUMANS

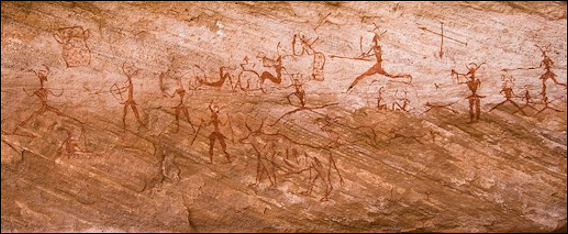

Saharan art Warfare — defined as organized group combat as opposed to acts of individual violence — is thought to have evolved around the time agriculture and villages developed, with idea that it became necessary when there was turf to defend, covet and fight over. Dr. Steven A LeBlanc of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard and author of a book called “Constant Battles,” told the New York Times, “War is universal and goes back deep into human history” and it is a myth that once people were “sublimely peaceful."

A site in northern Iraq, dated to 10,000 years ago, contains maces and arrowheads found with skeletons and defensive walls — thought to evidence of early warfare. Forts, dated to 5000 B.C., have been found in southern Anatolia. Other early evidence of war includes: 1) a battle scene, dated to between 4300 and 2500 B.C., with groups of men firing bows and arrow at each other in a rock painting in Tassili n’Ajjer, a Saharan plateau in southeastern Algeria; 2) a pile of decapitated human skeletons, dated to 2400 B.C., found at the bottom of a well near Handan, China, 250 miles southwest of Beijing; 3) paintings, dated to 5000 B.C., of an execution, found in a cave in Remigia cave, and a clash between archers from Morella la Vella in eastern Spain.

E. O. Wilson wrote: “Tribal aggressiveness goes back well beyond Neolithic times, but no one as yet can say exactly how far. It could have begun at the time of Homo habilis, the earliest known species of the genus Homo, which arose between 3 million and 2 million years ago in Africa. Along with a larger brain, those first members of our genus developed a heavy dependence on scavenging or hunting for meat. And there is a good chance that it could be a much older heritage, dating beyond the split 6 million years ago between the lines leading to modern chimpanzees and to humans. [Source: E. O. Wilson, Discover, June 12, 2012 /*/]

“Archaeologists have determined that after populations of Homo sapiens began to spread out of Africa approximately 60,000 years ago, the first wave reached as far as New Guinea and Australia. The descendants of the pioneers remained as hunter-gatherers or at most primitive agriculturalists, until reached by Europeans. Living populations of similar early provenance and archaic cultures are the aboriginals of Little Andaman Island off the east coast of India, the Mbuti Pygmies of Central Africa, and the !Kung Bushmen of southern Africa. All today, or at least within historical memory, have exhibited aggressive territorial behavior. *\

“History is a bath of blood,” wrote William James, whose 1906 antiwar essay is arguably the best ever written on the subject. “Modern man inherits all the innate pugnacity and all the love of glory of his ancestors. Showing war’s irrationality and horror is of no effect on him. The horrors make the fascination. War is the strong life; it is life in extremis; war taxes are the only ones men never hesitate to pay, as the budgets of all nations show us.” *\

RELATED ARTICLES:

STONE AGE AND BRONZE AGE WEAPONS AND FORTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

STONE AGE AND BRONZE AGE VIOLENCE AND MASS MURDER europe.factsanddetails.com

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Warfare in Neolithic Europe: An Archaeological and Anthropological Analysis” by Julian Heath (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Shepherd Protects Their Flock: Looking at Warfare from the Neolithic to Sumerians” (2021) by Chris Flaherty Amazon.com;

“Practice and Prestige: An Exploration of Neolithic Warfare, Bell Beaker Archery, and Social Stratification from an Anthropological Perspective” by Jessica Ryan-despraz (2022) Amazon.com;

“Emergent Warfare in Our Evolutionary Past” by Nam C Kim, Marc Kissel (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Warfare: Prehistories of Raiding and Conquest” by Elizabeth N. Arkush and Mark W. Allen (2008) Amazon.com;

“Warrior Scarlet” by Rosemary Sutcliff (1958) Novel Amazon.com;

“After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations” by Eric H. Cline (2024) Amazon.com;

“Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States” by James C. Scott (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution” by Susan Meyer (2016) Amazon.com;

“Constant Battles: The Myth of the Peaceful, Noble Savage” by Steven Le Blanc and Katherine E. Register (2003) Amazon.com;

“Warless Societies and the Origin of War” by Raymond C. Kelly (2000) Amazon.com;

“Massacres: Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology Approaches” by Cheryl P. Anderson and Debra L. Martin (2018) Amazon.com;

“War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage” by Lawrence H. Keeley (1997) Amazon.com;

“Arrowpoints, Spearheads, and Knives of Prehistoric Times” by Thomas Wilson (2022) Amazon.com

Early Evidence of Warfare — Jebel Sahaba in Sudan

The earliest evidence of war comes from a cemetery in the Nile Valley in Sudan. Discovered in the mid-1960s and dated to 13,400 years ago, the cemetery contains 61 skeletons, 24 of which were found near projectiles regarded as weapons and 20 of which had wounds. The victims died at a time the Nile was flooding, causing a severe ecological crisis. The site, known as Site 117, is located at Jebel Sahaba in Sudan. The victims included men, women and children who died violently. Some were found with spear points in near the head and chest that strongly suggest they were not offerings but weapons used to kill the victims. There is also evidence of clubbing — crushed bones an the like. Since there were so many bodies, one archaeologist surmised, "It looks like organized, systematic warfare." [Source: History of Warfare by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

According to Reuters: “Hunter-gatherers lived in the Nile Valley at the time, before the advent of agriculture. They hunted mammals such as antelope, caught fish and collected plants and roots. Their groups were small, perhaps not exceeding a hundred. While it is difficult to know why they fought, it came during a time of climate change in the region from a dry period to a wetter one along with severe Nile flooding episodes, possibly triggering competition among rival clans for resources and territory. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, May 28, 2021]

Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In the early 1960s, archaeologists from around the world descended on the Upper Nile Valley. They were scrambling to excavate ahead of the construction of the Aswan High Dam, which would submerge dozens of archaeological sites. While excavating the remains at Jebel Sahaba, the late archaeologist Fred Wendorf of Southern Methodist University noticed unmistakable signs of violence — broken bones, smashed skulls, and stone projectiles embedded in the people’s bones or lying near their bodies. He concluded that they were victims of a battle or massacre. At the time, the idea of organized warfare in the distant past was revolutionary. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2022]

“Prevailing archaeological doctrine in the peace-and-love era of the 1960s held that war and violence were modern inventions,” says Christopher Knüsel, a physical anthropologist at the University of Bordeaux. “There was a long period when archaeologists said warfare didn’t happen in prehistory.” For decades after their discovery, scholars pointed to the skeletons of Jebel Sahaba as the earliest evidence of violence, and even warfare, in deep prehistory. But at the time of the dig, the science of physical anthropology — the investigation of human bones for clues to how people lived and died — was in its infancy, and no comprehensive analysis of the remains was undertaken.

Jebel Sahaba — Evidence of Continual Warfare, Not Just One Battle

In 2014, 50 years after the original excavation at Jebel Sahaba, Isabelle Crevecoeur, an archaeologist with the French National Center for Scientific Research, decided to take a fresh look at the remains found there as part of her research on the causes of the millennia-long shift from hunting and gathering to herding and farming in the Nile Valley. Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology Magazine: She thought one way to shed light on this question might be to reexamine the bones from Jebel Sahaba, now housed in the British Museum. “There was a lot of fantasy around this cemetery,” Crevecoeur says. She and a team of physical anthropologists examined each skeleton and identified more than 100 previously undiscovered signs of trauma or violence, including evidence of arrow strikes. “Methods have really advanced, especially the way we look at cut marks and trauma,” says Daniel Antoine, curator of bioarchaeology at the British Museum. Until recently, researchers weren’t even certain what arrow strikes look like on bone, but new 3-D imaging techniques have made it possible to identify them. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2022]

The team’s findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports in May 2021, suggest that the cemetery wasn’t a mass grave resulting from a single battle, but something perhaps grimmer: evidence of decades of continual violence among neighboring groups in the form of frequent raids, sneak attacks, and ambushes. Crevecoeur identified numerous skeletons with both healed and unhealed wounds — people who had survived one violent encounter, only to be slain months or years later. On a battlefield, the dead are mostly people in the prime of their lives — for example, young men defending their village. But the Jebel Sahaba skeletons belong mostly to the very young and very old. Crevecoeur suggests that young, healthy people are absent because they would have been more likely to survive an ambush, escape an attack, or recover from their wounds. Equally grim are the individual wounds, including fractured hands and forearms perhaps incurred as people died trying to ward off blows. Some skeletons have evidence of arrow strikes and blows to their backs, as though the people had been struck down while attempting to flee.

Observed osseous lesions on JS 14l Center: schematic scheme of JS 14's skeletal preservation; Grey parts represent preserved bones; star = blunt force trauma, full star = unhealed puncture, open circle = perforations, yellow diamond = embedded artefact in a puncture, dash = drags traces of projectile impacts, line = cutmark. Box no. 1: lesions of the frontal bone on JS 14. Left: superior view of the frontal bone with, below, the magnification in frontal view of the red box showing the blunt force trauma and the embedded lithic (white oval) with hinge fractures; Right: left lateral view of the frontal bone displaying the projectile perforation. Red and white stars are reference points for the magnified area; a = hinge fractures at the level of the entrance of the projectile; b = crushing fractures on the border of the perforation; c = endocranial view of the internal beveling. Box no. 2: Projectile impact marks on the left femur of JS 14. Left: anterior view of the preserved part of the left femur. a = close up on the two set of drag marks located on the antero-lateral side of the shaft. White star put as reference point for the magnified area. b = detailed view of the superior drag revealing the wide flat bottom of the groove and the parallel microstriations (magnification ×245).

Reuters reported: The extensive and indiscriminate violence affected men and women equally, with children as young as 4 also wounded. “"It appears that one of the main lethal properties sought was to slash and cause blood loss," Crevecoeur said. While spears and arrows can be delivered from a distance, there also was evidence of close combat with numerous instances of parry fractures — blows to the forearm sustained when the arm is raised to protect the head — and broken hand bones. “"Unlike a specific battle or short war, violence appears to have unfortunately been a regular occurrence and part of the daily fabric of their lives," said study co-author Daniel Antoine, acting head of the Department of Egypt and Sudan and curator of bioarchaeology at the British Museum in London. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, May 28, 2021]

When their analysis was complete, the team found that more than 60 percent of the skeletons had visible signs of trauma. “That’s off the scale,” says Knüsel. “This suggests there’s something really unusual happening.” Crevecoeur thinks she knows what. Around 13,000 years ago, the once-lush Nile Valley began to dry up. Within a few millennia, it was essentially a desert oasis hundreds of miles long. For the first time, people living along the river had to compete for resources. “It’s not difficult to imagine a long-lasting climate of tension between groups,” Crevecoeur says.

Her findings echo discoveries elsewhere in the world that suggest violence was far more common in prehistory than once thought."We believe our findings have important implications to the debate about the causes and form of warfare," Crevecoeur said. "What is certain is that acts of violence are recorded since hundreds of thousands of years ago, and are not restricted to our species — for example, also Neanderthals. But their motives are probably as complex and varied as we can imagine." “Science is constantly evolving, and these multiple violent events highlight that violence’s cause is more complex than a single battle,” says Antoine. “As long as we curate the dead with care, respect, and dignity, these bodies are windows into the past other sources can’t address.”

Inter-Group Warfare in Nataruk, Kenya 10,000 Years Ago

Nataruk, a 10,000-year-old site in Kenya, contains the earliest known evidence of inter-group conflict. Nikhil Swaminathan wrote in Archaeology magazine: Organized aggression is typically associated with disputes over ownership of land or possessions. But the 10,000-year-old remains of 27 individuals discovered at what was once the southwestern edge of Kenya’s Lake Turkana suggest that this may not always have been the case. The unburied bodies, found at a site called Nataruk, were of hunter-gatherers and were unaccompanied by evidence of settlements or valuables. Instead, they paint a picture of pure carnage: The bones of 21 adults and six children show lesions most likely resulting from arrows and clubs. Weapons found at the site were made from obsidian sourced from afar, indicating the attackers were not local. [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

“The deaths at Nataruk are testimony to the antiquity of inter-group violence and war,” lead author Marta Mirazon Lahr, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement. She told Smithsonian, “What we see at the prehistoric site of Nataruk is no different from the fights, wars and conquests that shaped so much of our history, and indeed sadly continue to shape our lives.” [Source: Sarah Kaplan, Washington Post, April 1, 2016 \=]

Mirazon Lahr believes that people have always been prepared to fight for what they want, and that the formation of groups results in cultural divisions, thereby justifying warfare. These preconditions for battle “have existed for a very long time,” she says, “independent of the development of farming, material wealth, civilizations, and social hierarchies.” Within this context, the simple choice to hunt or feast on the beach at Nataruk, a plum spot on a lake almost fully encircled by mountains, where animals came for food and water, could have sealed the deceased’s fate.

The remains were discovered entirely by accident. Mirazon-Lahr had planned to explore a sediment layer dating to the time when the first Homo sapiens lived in the area, but her team first found 12 skeletons emerging from the ground due to erosion.Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine:“Archaeological evidence of prehistoric warfare is hard to find, and mostly comes from much later villages or settlements. This had previously led researchers to believe that sedentism was a prerequisite for organized conflict. What is interesting about the incident at Nataruk is that it appears to have occurred between groups of hunter-gatherers, and the discovery is upending assumptions about what provokes violence between groups of people. According to Mirazon-Lahr, the area around Lake Turkana was an excellent hunting ground 10,000 years ago — a paradise, in effect. The attackers were probably not starving and probably did not go to war as a last resort. Lake Turkana is surrounded by mountains, which might have allowed one group of people to control access to the area near Nataruk. The critical issue was not sedentism, thinks Mirazon-Lahr, but differences in wealth. “In the world of hunter-gatherers,” she says, “wealth is probably defined as access to the best hunting grounds.”

Evidence of Inter-Group Warfare in Nataruk, Kenya

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: The massacre took place roughly 10,000 years ago, but the victims’ bones weren’t buried; they lay on the ground at the site of Nataruk near the shore of Kenya’s Lake Turkana. Ten of the skeletons show signs of violent deaths: heads had been smashed with clubs, an obsidian arrow tip was embedded in the top of one skull, and another person’s face has a deep cut that may have come from a club inset with obsidian blades. Mirazon-Lahr believes the attack was not the result of a chance encounter between bands of hunters because the wounds were caused by fragile weapons that would have had little use in hunting.[Source: Zach Zorich, May-June 2016]

Sarah Kaplan wrote in the Washington Post: “The skeletons told an alarming tale: One belonged to a woman who died with her hands and feet bound. The hands, chest and knees of another were fragmented and fractured — likely evidence of having been beaten to death. Stone projectiles protruded ominously from skulls; razor-sharp obsidian blades glittered in the dirt. [Source: Sarah Kaplan, Washington Post, April 1, 2016 \=]

“The scattered, scrambled remains of 27 men, women and children seemed to illustrate that conflict is not simply a symptom of our modern sedentary societies and expansionist ambitions. Even when we existed in isolated bands roaming across vast, unsettled continents, we showed capacity for hostility, violence and barbarism. One of the members of the “Nataruk Group” was a pregnant woman; inside her skeleton, scientists found her fetus’s fragile bones.” \=\

Is War Inevitable?

Harvard sociobiologist E. O. Wilson wrote: “Our bloody nature, it can now be argued in the context of modern biology, is ingrained because group-versus-group competition was a principal driving force that made us what we are. In prehistory, group selection (that is, the competition between tribes instead of between individuals) lifted the hominins that became territorial carnivores to heights of solidarity, to genius, to enterprise—and to fear. Each tribe knew with justification that if it was not armed and ready, its very existence was imperiled. [Source: E. O. Wilson, Discover, June 12, 2012 /*/]

“Throughout history, the escalation of a large part of technology has had combat as its central purpose. Today the calendars of nations are punctuated by holidays to celebrate wars won and to perform memorial services for those who died waging them. Public support is best fired up by appeal to the emotions of deadly combat, over which the amygdala—a center for primary emotion in the brain—is grandmaster. We find ourselves in the “battle” to stem an oil spill, the “fight” to tame inflation, the “war” against cancer. Wherever there is an enemy, animate or inanimate, there must be a victory. You must prevail at the front, no matter how high the cost at home. /*/

“Any excuse for a real war will do, so long as it is seen as necessary to protect the tribe. The remembrance of past horrors has no effect. From April to June in 1994, killers from the Hutu majority in Rwanda set out to exterminate the Tutsi minority, which at that time ruled the country. In a hundred days of unrestrained slaughter by knife and gun, 800,000 people died, mostly Tutsi. The total Rwandan population was reduced by 10 percent. When a halt was finally called, 2 million Hutu fled the country, fearing retribution. The immediate causes for the bloodbath were political and social grievances, but they all stemmed from one root cause: Rwanda was the most overcrowded country in Africa. For a relentlessly growing population, the per capita arable land was shrinking toward its limit. The deadly argument was over which tribe would own and control the whole of it. /*/

Saharan rock art

Universality of Conflict?

E. O. Wilson wrote: “Once a group has been split off from other groups and sufficiently dehumanized, any brutality can be justified, at any level, and at any size of the victimized group up to and including race and nation. And so it has ever been. A familiar fable is told to symbolize this pitiless dark angel of human nature. A scorpion asks a frog to ferry it across a stream. The frog at first refuses, saying that it fears the scorpion will sting it. The scorpion assures the frog it will do no such thing. After all, it says, we will both perish if I sting you. The frog consents, and halfway across the stream the scorpion stings it. Why did you do that, the frog asks as they both sink beneath the surface. It is my nature, the scorpion explains. [Source: E. O. Wilson, Discover, June 12, 2012 /*/]

“War, often accompanied by genocide, is not a cultural artifact of just a few societies. Nor has it been an aberration of history, a result of the growing pains of our species’ maturation. Wars and genocide have been universal and eternal, respecting no particular time or culture. Archaeological sites are strewn with the evidence of mass conflicts and burials of massacred people. Tools from the earliest Neolithic period, about 10,000 years ago, include instruments clearly designed for fighting. One might think that the influence of pacific Eastern religions, especially Buddhism, has been consistent in opposing violence. Such is not the case. Whenever Buddhism dominated and became the official ideology, war was tolerated and even pressed as part of faith-based state policy. The rationale is simple, and has its mirror image in Christianity: Peace, nonviolence, and brotherly love are core values, but a threat to Buddhist law and civilization is an evil that must be defeated. /*/

“Since the end of World War II, violent conflict between states has declined drastically, owing in part to the nuclear standoff of the major powers (two scorpions in a bottle writ large). But civil wars, insurgencies, and state-sponsored terrorism continue unabated. Overall, big wars have been replaced around the world by small wars of the kind and magnitude more typical of hunter-gatherer and primitively agricultural societies. Civilized societies have tried to eliminate torture, execution, and the murder of civilians, but those fighting little wars do not comply. /*/

Population Pressures and War

world population

E. O. Wilson wrote: ““The principles of population ecology allow us to explore more deeply the roots of mankind’s tribal instinct. Population growth is exponential. When each individual in a population is replaced in every succeeding generation by more than one—even by a very slight fraction more, say 1.01—the population grows faster and faster, in the manner of a savings account or debt. A population of chimpanzees or humans is always prone to grow exponentially when resources are abundant, but after a few generations even in the best of times it is forced to slow down. Something begins to intervene, and in time the population reaches its peak, then remains steady, or else oscillates up and down. Occasionally it crashes, and the species becomes locally extinct.[Source: E. O. Wilson, Discover, June 12, 2012 /*/]

“What is the “something”? It can be anything in nature that moves up or down in effectiveness with the size of the population. Wolves, for example, are the limiting factor for the population of elk and moose they kill and eat. As the wolves multiply, the populations of elk and moose stop growing or decline. In parallel manner, the quantity of elk and moose are the limiting factor for the wolves: When the predator population runs low on food, in this case elk and moose, its population falls. In other instances, the same relation holds for disease organisms and the hosts they infect. As the host population increases, and the populations grow larger and denser, the parasite population increases with it. In history diseases have often swept through the land until the host populations decline enough or a sufficient percentage of its members acquire immunity. /*/

“There is another principle at work: Limiting factors work in hierarchies. Suppose that the primary limiting factor is removed for elk by humans’ killing the wolves. As a result the elk and moose grow more numerous, until the next factor kicks in. The factor may be that herbivores overgraze their range and run short of food. Another limiting factor is emigration, where individuals have a better chance to survive if they leave and go someplace else. Emigration due to population pressure is a highly developed instinct in lemmings, plague locusts, monarch butterflies, and wolves. If such populations are prevented from emigrating, the populations might again increase in size, but then some other limiting factor manifests itself. For many kinds of animals, the factor is the defense of territory, which protects the food supply for the territory owner. Lions roar, wolves howl, and birds sing in order to announce that they are in their territories and desire competing members of the same species to stay away. /*/

War, Territory and Resources

E. O. Wilson wrote: “Humans and chimpanzees are intensely territorial. That is the apparent population control hardwired into their social systems. What the events were that occurred in the origin of the chimpanzee and human lines—before the chimpanzee-human split of 6 million years ago—can only be speculated. I believe that the evidence best fits the following sequence. The original limiting factor, which intensified with the introduction of group hunting for animal protein, was food. Territorial behavior evolved as a device to sequester the food supply. Expansive wars and annexation resulted in enlarged territories and favored genes that prescribe group cohesion, networking, and the formation of alliances. [Source: E. O. Wilson, Discover, June 12, 2012 /*/]

“For hundreds of millennia, the territorial imperative gave stability to the small, scattered communities of Homo sapiens, just as they do today in the small, scattered populations of surviving hunter-gatherers. During this long period, randomly spaced extremes in the environment alternately increased and decreased the population size so that it could be contained within territories. These demographic shocks led to forced emigration or aggressive expansion of territory size by conquest, or both together. They also raised the value of forming alliances outside of kin-based networks in order to subdue other neighboring groups. /*/

“Ten thousand years ago, at the dawn of the Neolithic era, the agricultural revolution began to yield vastly larger amounts of food from cultivated crops and livestock, allowing rapid growth in human populations. But that advance did not change human nature. People simply increased their numbers as fast as the rich new resources allowed. As food again inevitably became the limiting factor, they obeyed the territorial imperative. Their descendants have never changed. At the present time, we are still fundamentally the same as our hunter-gatherer ancestors, but with more food and larger territories. Region by region, recent studies show, the populations have approached a limit set by the supply of food and water. And so it has always been for every tribe, except for the brief periods after new lands were discovered and their indigenous inhabitants displaced or killed. /*/

“The struggle to control vital resources continues globally, and it is growing worse. The problem arose because humanity failed to seize the great opportunity given it at the dawn of the Neolithic era. It might then have halted population growth below the constraining minimum limit. As a species we did the opposite, however. There was no way for us to foresee the consequences of our initial success. We simply took what was given us and continued to multiply and consume in blind obedience to instincts inherited from our humbler, more brutally constrained Paleolithic ancestors. /*/

No, War Is Not Inevitable.

John Horgan wrote in Discover: “I have one serious complaint against Wilson, though. In his new book and elsewhere, he perpetuates the erroneous—and pernicious—idea that war is “humanity’s hereditary curse.” As Wilson himself points out, the claim that we are descended from a long line of natural-born warriors has deep roots—even the great psychologist William James was an advocate—but like many other old ideas about humans, it’s wrong. [Source: John Horgan, science writer, Discover, June 2012 /*/]

“The modern version of the “killer ape” theory depends on two lines of evidence. One consists of observations of Pan troglodytes, or chimpanzees, one of our closest genetic relatives, banding together and attacking chimps from neighboring troops. The other derives from reports of intergroup fighting among hunter-gatherers; our ancestors lived as hunter-gatherers from the emergence of the Homo genus until the Neolithic era, when humans began settling down to cultivate crops and breed animals, and some scattered groups still live that way. /*/

“But consider these facts. Researchers did not observe the first deadly chimpanzee raid until 1974, more than a decade after Jane Goodall started watching chimps at the Gombe reserve. Between 1975 and 2004, researchers counted a total of 29 deaths from raids, which comes to one killing for every seven years of observation of a community. Even Richard Wrangham of Harvard University, a leading chimpanzee researcher and prominent advocate of the deep-roots theory of war, acknowledges that “coalitionary killing” is “certainly rare.” /*/

“Some scholars suspect that coalitionary killing is a response to human encroachment on chimp habitat. At Gombe, where the chimps were well protected, Goodall spent 15 years without witnessing a single lethal attack. Many chimpanzee communities—and all known communities of bonobos, apes that are just as closely related to humans as chimps—have never been seen engaging in intertroop raids. /*/

“Even more important, the first solid evidence of lethal group violence among our ancestors dates back not millions, hundreds of thousands, or even tens of thousands of years, but only 13,000 years. The evidence consists of a mass grave found in the Nile Valley, at a location in modern-day Sudan. Even that site is an outlier. Virtually all other evidence for human warfare—skeletons with projectile points embedded in them, weapons designed for combat (rather than hunting), paintings and rock drawings of skirmishes, fortifications—is 10,000 years old or less. In short, war is not a primordial biological “curse.” It is a cultural innovation, an especially vicious, persistent meme, which culture can help us transcend. /*/

“The debate over war’s origins is vitally important. The deep-roots theory leads many people, including some in positions of power, to view war as a permanent manifestation of human nature. We have always fought, the reasoning goes, and we always will, so we have no choice but to maintain powerful militaries to protect ourselves from our enemies. In his new book, Wilson actually spells out his faith that we can overcome our self-destructive behavior and create a “permanent paradise,” rejecting the fatalistic acceptance of war as inevitable. I wish he would also reject the deep-roots theory, which helps perpetuate war.” /*/

Chimpanzee Warfare

Saharan art Chimpanzees share the human proclivity to territorial aggression and scientists are studying this kind of behavior among chimps to gain insights into the behavior of ancient humans. Studies of modern hunter gatherers show that when one group outnumbers another group it may attack and kill them. Chimpanzee display similar behavior.

In 1974 scientists at Gombe Reserve in Tanzania observed a gang of five chimpanzees attack a single male and hit, kick and bite him for twenty minutes. He suffered terrible wounds and was never seen again. A month later, a similar fate befell a male attacked by three members of the gang of five and he too disappeared — apparently dying from his wounds. The two victims were members of a splinter groups with seven males, three females and their young that were all eventually killed in a "war" that lasted four years. The victims were killed by a rival group that appeared to be attempting to claim territory they had previously lost or were seeking revenge for the transfer of a female from the aggressors group to the victims group. The "war" was the first example of inter-community violence ever observed in the animal kingdom.

In the 1990s scientists in Gabon noted that the population of chimpanzees had been reduced by 80 percent in areas logged in Lope National Park and the surviving animals demonstrated unusual aggressive and agitated behavior. Logging in Gabon rain's forest reportedly touched of a chimpanzee war that may have claimed the lives of as many 20,000 chimpanzees. Even though only about 10 percent of the trees had been selectively logged in the areas where the war occurred, the lost trees seem to have set of violent territorial battles. Biologists say the chimps near the logging areas were disturbed by the presence of humans and the noise generated by the logging machines and moved out of the area, fighting with and displacing other chimp communities, which in turn attacked their neighbor who then in turn attack their neighbors setting off a chain reaction of aggression and violence.

Harvard sociobiologist E. O. Wilson wrote: “A series of researchers, starting with Jane Goodall, have documented the murders within chimpanzee groups and lethal raids conducted between groups. It turns out that chimpanzees and human hunter-gatherers and primitive farmers have about the same rates of death due to violent attacks within and between groups. But nonlethal violence is far higher in the chimps, occurring between a hundred and possibly a thousand times more often than in humans. [Source: E. O. Wilson, Discover, June 12, 2012 /*/]

“The patterns of collective violence in which young chimp males engage are remarkably similar to those of young human males. Aside from constantly vying for status, both for themselves and for their gangs, they tend to avoid open mass confrontations with rival troops, instead relying on surprise attacks. The purpose of raids made by the male gangs on neighboring communities is evidently to kill or drive out their members and acquire new territory. There is no certain way to decide on the basis of existing knowledge whether chimpanzees and humans inherited their pattern of territorial aggression from a common ancestor or whether they evolved it independently in response to parallel pressures of natural selection and opportunities encountered in the African homeland. From the remarkable similarity in behavioral detail between the two species, however, and if we use the fewest assumptions required to explain it, a common ancestry seems the more likely choice. /*/

Violence in the Ancient Middle East Spiked When States and Empires Formed, Study of Skulls Reveals

Research into nearly 12,000 years of violence in the Middle East revealed that bloodshed soared rose when proto-states and state-level society, began to form about 6,500 years ago and peaked again during a period of drought and mass migrations about 3,200 years ago, according to an analysis of battered human skulls and bones. Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: The skulls and bones — from over 3,500 people injured in conflicts in the Middle East during pre-Classical times (12000 B.C. to 400 B.C.) — came from the geographical region that includes Turkey, the Levant (the land around the eastern Mediterranean), Mesopotamia and Iran. These human remains were studied by an international research team interested in testing hypotheses about the rise and fall of violence in premodern times, according to a study published October 9, 2023 in the journal Nature Human Behaviour. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, published October 17, 2023]

The team investigated cranial trauma and weapon-related wounds in the skeletons of people who lived in the Middle East during one of four time periods: the Neolithic (12000 to 4500 B.C.), the Copper Age (4500 to 3,300 B.C.), the Bronze Age (3300 to 1200 B.C.) and the Iron Age (1200 to 400 B.C.). The ancient Middle East is an ideal place to look for clues to understanding violence in humans because this geographic area was crucial to several major innovations in human culture, from the domestication of plants and animals to the creation of the first cities beginning around 11,000 years ago.

The researchers' goal was to test assumptions about the level of violence in these time periods. For example, a low population density in the Neolithic period likely meant low levels of violence, while the emergence of states and empires in later periods may have increased interpersonal violence, particularly as people began to live close to one another in early cities.

Through their analysis of traumatic injuries identified on ancient skulls, the team found that the incidence of violence increased dramatically in the Copper Age, when large-scale organized conflict arose with the first proto-states, and then again in the Iron Age, due to major upheavals that included a 300-year drought and the rise of military superpowers such as the Assyrian Empire.

But a substantial decline in violence occurred in the Bronze Age between 3000 and 1500 B.C., the researchers found, in spite of numerous climate- and urbanism-related challenges. They concluded that it is likely "the violence decline took place at a time when early states achieved substantial capacities to reduce conflicts in their societies." "It seems quite clear that legal systems evolved rapidly through the Bronze Age, and even free citizens enjoyed some degree of protection from the law," study co-author Giacomo Benati, an economic historian at the University of Barcelona, told Live Science in an email. "This indicates that people had increasingly peaceful means to solve disputes."

Peace was short-lived, though, as the Iron Age saw unprecedented levels of inequality, diminishing resources, and a surge in warfare related to the rise of empires, such as that of the Hittites, who ruled over what is now part of Turkey. The discovery of upper-skull trauma in the Copper and Iron ages may suggest that "a blow to the head was possibly the most common way to kill in the pre-modern period," Benati said.

Debra Martin, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas who was not involved in the study but has expertise in ancient violence, said the study is interesting and based on solid data. "I applaud that the authors chose to not interpret the data to fit into one causal explanation," she told Live Science."Violence and conflict are often driven not only by external factors but also by ideology, beliefs and symbolism. In other words, it's complicated what drives violence."

Warfare at Tell Hamoukar in Syria 5,500 Years Ago

The oldest known example of large scale warfare is from a fierce battle that took place at Tell Hamoukar around 3500 B.C. Evidence of intense fighting include collapsed mud walls that had undergone heavy bombardment; the presence of 1,200 oval-sapped “bullets” flung from slings and 120 large round balls. Graves held skeletons of likely battle victims. Reichel told the New York Times the clash appeared to have been a swift, rapid attack: “buildings collapse, burning out of control, burying everything in them under a vast pile of rubble.”

No one knows who the attacker of Tell Hamoukar was but circumstantial evidence points to Mesopotamia cultures to the south. The battle may have been between northern and southern Near Eastern cultures when the two cultures were relative equally, with the victory by the south giving them an edge and paving the way for them to dominate the region. Large amount of Uruk pottery was found on layers just above the battle. Reichel told the New York Times,”If the Uruk people weren’t the ones firing the sling bullets, they certainly benefitted from it. They are all over this place right after its destruction.”

Discoveries at Tell Hamoukar have changed thinking about the evolution of civilization in Mesopotamia. It was previously though that civilization developed in Sumerian cities like Ur and Uruk and radiated outward in the form of trade, conquest and colonization. But findings in Tell Hamoukar show that many indicators of civilization were present in northern places like Tell Hamoukar as well as in Mesopotamia and around 4000 B.C. to 3000 B.C. the two placed were pretty equal.

Neolithic and Bronze Age Battles in France and Germany

According to Archaeology magazine: In northeastern France’s Alsace region, a team from the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research has discovered graphic evidence for a violent Neolithic-era clash of cultures. While digging in a fortified village dating to between 4400 and 4200 B.C., archaeologists unearthed a storage pit that held the mutilated remains of five men and one teenage boy, as well as four severed left arms. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2016]

Archaeologist Philippe Lefranc suggests the limbs were battlefield trophies, and that the skeletons belonged to members of a captured enemy war party. “I think we are seeing ritualized violence against captives who were initially alive,” says Lefranc. “It probably took place in the middle of the village during a victory celebration. All the remains were eventually thrown in a ritual refuse dump.” Lefranc thinks the enemy warriors were from a new population migrating into the area from the Paris Basin to the west. Despite losing this round, they eventually triumphed. At the end of the fifth millennium, the local pottery style and burial rituals were replaced by those of the newcomers, and all the old villages in Alsace were relocated.

One of Europe’s oldest battlefields is located in northeast Germany’s Tollense River Valley. Around 3,250 years ago, a clash involving some 2,000 warriors left a mile-long stretch of the river littered with weapons and dead bodies. Recent isotopic analysis of tooth enamel was able to narrow down the geographic origins of the combatants. While one group was local to the region, scientists determined that a second group was made up of diverse individuals who had traveled from southern Germany or central Europe to join the battle. [Source: Jason Urbanus Archaeology magazine, January-February 2018]

5,000-Year-Old Mass Grave in Spain Has Evidence of Repeated Battles

A study published November 2, 2023 in the journal Scientific Reports describes men, women and children with head trauma and arrow wounds buried in a mass grave in Spain 5,000 years ago. Archaeologists who studied the grave — located at the San Juan ante Portam Latinam (SJAPL) rock shelter, near the town of Laguardia in northern Spain, and first excavated in 1991 — said it contained evidence of sophisticated warfare. More than 300 skeletons, radiocarbon-dated to 3380 to 3000 B.C., were found in one mass burial, many of overlapping each other and in odd positions. Archaeologist also found dozens of flint arrowheads and blades, along with stone axes and personal ornaments. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, November 3, 2023]

Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: Researchers initially concluded that they'd found evidence of a Neolithic massacre. But a new analysis of the SJAPL skeletons has revealed that these people were most likely killed in separate raids or battles over a period of several months or years. Lead author of the study, Teresa Fernández-Crespo, an archaeologist at the University of Valladolid in Spain, and her team describe the healed and unhealed injuries on the SJAPL skeletons. They found a total of 107 cranial injuries, most of which were located on the top of the skull and likely correspond to blunt-force trauma, such as blows from stone maces or wooden clubs. Nearly five times as many males as females suffered cranial trauma, the researchers found.

Injuries on the rest of the skeletons were also examined. The team discovered 22 instances of trauma — mostly spiral or V-shaped fractures — affecting the limbs, as well as 25 injuries to other parts of the body. Like the skull injuries, these seem to have disproportionately affected men, who were nearly four times as likely as women to have evidence of bodily trauma. Arrowhead injuries were also strongly linked to male skeletons, suggesting men were more often exposed to long-range violence than women were.

All told, adolescent and adult males buried at SJAPL accounted for 97.6 percent of unhealed trauma and 81.7 percent of healed trauma recorded in skeletons whose biological sex could be estimated. This suggests, according to the study authors, that the mass grave represents "one or more 'war layers' resulting from battles and/or raids where the involvement of males was dominant." "We think we are seeing the result of a regional inter-group conflict" at SJAPL, Fernández-Crespo told Live Science. "Resource competition and social complexity could have been a source of tension, potentially escalating into lethal violence" between communities, she said.

These Late Neolithic communities — each of which consisted of a few hundred people — comprised mostly farmers, who cultivated wheat and barley and tended to domesticated herds of sheep, cattle and pigs. But additional evidence of illness and stress that the team found on the Neolithic skeletons suggests that food scarcity may have affected the people and potentially been a consequence of the violence. "This research presents a convincing case for interregional conflict where male combatants died in battle," Ryan Harrod, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Alaska Anchorage who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. "The fact there were more nonlethal compared to lethal injuries on the 338 individuals," Harrod said, shows that many people healed from their injuries, "which might indicate that the regional clashes were not epic battles or warfare."

Peaceful Jomon People in Japan

In a study published in the journal Biology Letters, researchers said they found little evidence of violence or warfare on Jomon people skeletons. Researchers in Japan searched the country looking for sites of violence similar to the one at Nataruk, described above, and found none, leading them to surmise that violence is not an inescapable aspect of human nature. [Source: Sarah Kaplan, Washington Post, April 1, 2016 \=]

Sarah Kaplan wrote in the Washington Post: “They found that the average mortality rate due to violence for the Jomon was just under 2 percent. (By way of comparison, other studies of the prehistoric era have put that figure somewhere around 12 to 14 percent.) What's more, when the researchers sought out “hot spots” of violence — places where lots of injured individuals were clustered together — they couldn't find any. Presumably, if the Jomon had engaged in warfare, archaeologists would have bunches of skeletons all in a heap...That no such bunches seemed to exist suggests that wars weren't being fought. \=\

Archaeologists have yet to find any evidence of battles or wars during the Jomon Period, a remarkable finding considering the period spanned 10,000 years. Other evidence of the peaceful nature of Jomon people includes: 1) no signs of walled settlements, defences, ditches or moats; 2) no finds of unusually large numbers of weapons such as lances, spears, bows and arrows; and 3) no evidence of human sacrifice nor masses of unceremonially dumped bodies. Nevertheless, there is evidence that violence and aggression occurred. The hip bone of a male individual, dated to the Initial Jomon period, was found at Kamikuroiwa Site in n Ehime Prefecture, Shikoku, that had been perforated by a bone point. Arrowheads have been found in bones and broken crania at other sites dated to the Final Jomon Period. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

See Separate Article: JOMON PEOPLE (10,500–300 B.C.): THEIR LIFESTYLE AND SOCIETY europe.factsanddetails.com

Study Concludes Warfare Isn’t Part of Human Nature

A study published in Science in July 2013 concluded that warfare is necessarily an intrisic part of primitive societies. Monte Morin wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “It's been argued that warfare is as old as humanity itself — that the affairs of primitive society were marked by chronic raiding and feuding between groups. Now, a new study argues just the opposite. After reviewing a database of present-day ethnographies for 21 hunter-gatherer societies — groups that most closely resemble our evolutionary past — researchers at Abo Akademi University in Finland concluded that early man had little need or cause for war. [Source: Monte Morin, Los Angeles Times, July 19, 2013 +||+]

“Though these so-called mobile forager band societies — referred to in the report as MFBS — were not free of violence, researchers said the mayhem was very unorganized and seldom involved rival groups. In fact, the violence practiced by these wandering societies was overwhelmingly murder, plain and simple, according to Douglas Fry, an anthropology professor, and Patrik Soderberg, a developmental psychology graduate student. "Many lethal disputes involved two men competing over a particular woman (sometimes the wife of one of them), revenge homicide exacted by family members of a victim (often aimed at the specific person responsible for the previous killing), and interpersonal quarrels of various kinds; for instance, stealing of honey, insults or taunting, incest, self-defense or protection of a loved-one," authors wrote. +||+

“The researchers examined 148 killings and their reported cause. For the most part, the 21 groups were peaceful, but one group in particular stood out for its violence, the Tiwi of Australia. They generated nearly half of the lethal events. "The findings suggest that MFBS are not particularly warlike if the actual circumstances of lethal aggression are examined. Fifty-five percent of the lethal events involved a sole perpetrator killing only one individual (64 percent if the atypical Tiwi are removed). One-person-killing-one-person reflects homicide or manslaughter, not coalitional killing or war," the authors wrote.

“Only 15 percent of the lethal events occurred across societal lines, however. The authors listed numerous factors that made warfare among hunter-gatherer societies very unlikely. Small group size, large foraging areas and low population density were not conducive to organized conflict. If groups didn't get along, they were more likely to put distance between them than fight, authors said. +||+

“Foraging societies are also more egalitarian than sedentary societies and lack clear leadership to organize for war. Likewise, their roaming lifestyle made it difficult to capitalize on conquest. "Typical spoils of war — material goods or stored food — are largely lacking, and the necessity of mobility makes the capture and containment of individuals against their will (e.g., slaves or brides) impractical," authors wrote. Because of this, the authors argue that warfare is a behavior that humans adopted more recently, after we abandoned a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.” +||+

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons Nataruk images from University College London and Nature

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books) and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024