CATALHOYUK LIFE

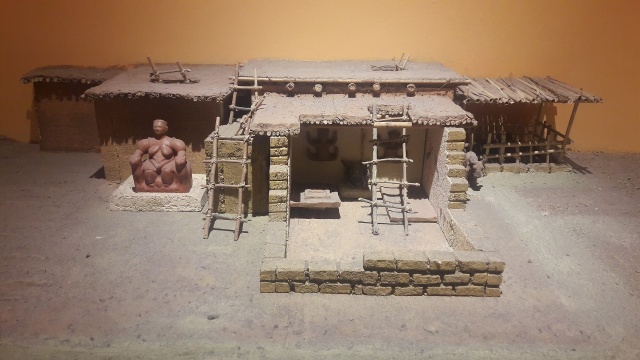

restoration of a room Çatalhöyük (668 kilometers 415 miles southeast of Istanbul) is widely accepted as being the world's oldest village or town. Established around 7500 B.C. , it covered 32 acres and was home to between 3000 to 8000 people. Because of the way of the houses are packed so closely together it is hard to dispute it as being anything other than a village or town. [Sources: Ian Hodder, Natural History magazine, June 2006; Michael Batler, Smithsonian magazine, May 2005; Orrin Shane and Mine Kucuk, Archaeology magazine, March/April 1998]

Archaeological work at Çatalhöyük has revealed a large community of Stone Age people beginning to reject nomadic life. Artifacts and structures uncovered at Çatalhöyük over the years suggest the people living at the site were pioneers of early farming and animal domestication. They cultivated wheat and barley and tended sheep and goats. Çatalhöyük has been a pioneer in many areas. The world’s first bread was found there as well as some of the earliest weavings. Some of the world’s oldest wooden artifacts, wall paints and paintings were found there.

The inhabitants of Catalhoyuk lived in mud-brick and timber houses built around courtyards. The village had no streets or alleyways. Houses were packed so close together people entered their houses through their roofs and often went from place to place via the roofs, which were made of wood and reeds plastered with mud and often reached by ladders and stairways. Bone tools for sewing and weaving have been found at Çatalhöyük.

People appear to have lived in family groups.Archaeological work at Çatalhöyük has unearthed numerous levels of close-knit households. Bodies were normally buried under houses in burial pits, suggesting a sense of community. Researchers have used dental remains from 266 individuals to determine how they were related.

At its peak, from 7100 to 5700 B.C., Çatalhöyük’s 8,000 inhabitants lived in densely packed one-room houses without doors or windows, which were entered through small openings in their roofs. According to Archaeology magazine: A new experimental archaeology project has helped researchers determine that when fires were burning in these houses’ ovens, the lack of ventilation would have exposed residents to dangerous levels of air pollution. This likely caused respiratory illnesses and other ailments. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September 2021]

RELATED ARTICLES:

CATALHOYUK, WORLD'S OLDEST TOWN factsanddetails.com ;

NEOLITHIC SITES IN ANATOLIA (TURKEY) factsanddetails.com

Catalhoyuk Lifestyle

The inhabitants of Catalhoyuk herded goats and sheep, hunted horse and wild cattle (aurochs) and deer, grew emmer wheat, peas, bitter vetch lentils and other legumes and cereals, and collected wild plant foods such as tubers from the nearby marshes. Evidence for these food includes food samples found by the ovens and accumulations of goat and sheep dung consistent with that of found modern animals pens. This showed that early farming emerged here very early as it dd in the Levant and adjacent areas of the Middle East. There is also evidence of an irrigation system at Catalhoyuk, which was previously thought to have originated in Mesopotamia.

mother goddess

Artifacts unearthed at Catalhoyuk include the world’s earliest known pottery, polished obsidian mirrors, bone hook-an-eye closures, preserved basketry, textiles, carved wooden utensils,, sophisticated obsidian tools, and superbly crafted flint daggers with bone handles carved in the form on animals. Unusual objects include a fishhook pendant made from a split boar’s tusk and animal-horn figures imbedded into the walls of homes.

Finely crafted tools included carved obisdian spear points which they crafted inside their houses. Some kind of trade was going on. Valuable obsidian was obtained from volcanic peaks to the north in Cappadochia; dates came from Mesopotamia or the Levant; and shells came from the Red Sea.

Collections of clay balls have been found in the hearths and oven. It is believed to these were set in a basket or a skin to boil water in a manner that is similar to the way some traditional societies today use heated rocks. At Catalhoyuk clay balls were used instead of rocks because rocks were in short supply. Judging from scraps and materials found around the hearth, the hearth areas were used to chip obsidian into tools and make beads as well as cook. Preparing food and making tools was generally done in one of the side rooms. They were not done in the rooms with plastered art.

Catalhoyuk Religion

Many of the buildings contained rooms with platforms and scaffolds, some with two or three tiers, with life-size plaster heads of bulls, sheep and goats, with real horns, on them. In one room there was a plaster bench, long enough for a person to lie on, with six pairs of auroch horns mounted on them. Some of theme had murals and reliefs placed near them. It is widely believed that these platforms are religious shrines.

Cristina Belmonte wrote in National Geographic History: The relationship with animals depicted in their art must have been a powerful element of local beliefs. Perhaps the most important of all was the wild bull, whose horns were placed on platforms or in other parts of the home. The bones of wild animals, usually male, were deposited as offerings when a house was built or abandoned. Researchers speculate that the occupants did so in the hope of overcoming their fear of nature or to be close to its powerful spirit. [Source: Cristina Belmonte, National Geographic History, March 27, 2019]

James Mellaart, the archaeologist who discovered Catalhoyuk, believes that religion was central to lives of the people of Catalhoyuk. He concluded they worshiped a mother goddess, based on the large number of female figures, made of fired clay or stone, found at the site. One baked clay figure discovered by Mellaart in a grain bin is about 20 centimeters tall and depicts a seated woman. She is quite fat with sagging breast, legs and arms, and a drooping belly that covers her crotch. Her arms sit on feline arm rests. Archaeologists believe the figurine was placed in the grain bin as an offering in preparation of rebuilding the house.

According to Archaeology magazine: “In a Neolithic dwelling at the site of Çatalhöyük in southern Turkey, archaeologists have uncovered a limestone female figurine that is at least 8,000 years old. While many such figurines have been found there previously, most are made of clay. Further, few display the kind of high-quality craftsmanship and level of detail evident in this example, which, excavators say, would have been executed by a skilled artisan using flint or obsidian tools. Interpretations of these robust female figurines differ. Some researchers consider them fertility goddesses, while others suggest they may represent older women of high status in the community. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

Catalhoyuk Burials

Excavations of burial pits have revealed newborns and 60-years-old adults. The bodies of the dead were tightly flexed and buried in plastered-over pits underneath rooms inside the houses. Excavations have shown that the rooms were used not long after the bodies were buried or after the pits were reopened and new bodies were placed inside.

Bury the dead under houses was common in early agricultural villages in the Near East. One dwelling at Catalhoyuk was found to have 64 skeletons buried underneath it. Some of the dead were buried on their sided with their legs drawn to their chest in the fetal position and their arms crossed in front of their chest, holding large objects. Paintings depict vultures flying over headless human bodies, suggesting the practice used by Tibetans and Parsis and others of setting the deceased outside for the bodies can be naturally defleshed before being buried.

Bones found by Mellaart were often jumbled, suggesting the bones had initially been buried somewhere else of defleshed and reburied under the house platform. Those found by Hodder were buried intact under the platforms. One buried woman was found holding a plastered skull, The skull belonged to an old man. The skulls’s face was covered with layers of soft, white plaster, much of it painted with ocher, a red pigment. The eye sockets were filled with plaster and a plaster nose had been applied. Archaeologists have speculated that its may have belonged to a revered ancestor or relative of the deceased. The skull was the first plastered skull found at Catalhoyuk. One other has been found at a Neolithic site in Turkey. Plastered skulls are associated with the Biblical city of Jericho and have been found in Jordan and Syria.

Çatalhöyük People Painted Their Dead to Match Dwelling Wall Paintings

The people of Çatalhöyük engaged in unusual funeral rites that involved painting of dead bodies and houses and burying the dead inside the houses. A team led by Eline Schotsman from the PACEA laboratory at the University of Bordeaux has examined human remains at the site with the aim of understanding the use of pigments in funeral rituals at Çatalhöyük. The results of their work were published in March 2022 the journal Scientific Reports. [Source: Cassidy Ward, SYFY March 27, 2022]

The majority of the deceased were buried and left in the ground.. A small portion of the dead, about six percent, received special treatment. They were painted with various pigments.“This is the beginning of social differentiation, but we’re not sure why some were painted. It isn’t based on age, or sex, or specific families. At the moment, we don’t really have an answer. We think it was a kind of social memory,” Schotsman told SYFY WIRE.

Paintings in the houses appear to match up with the painted remains, suggesting they were done at, or around, the same time. The same pigment were added to the remains and to the wall painting in the dwellings. “Blue and green colors were used for women and children only, which is quite special. Cinnabar was only used for males and only found as a head band. Ochre was used for everyone,” Schotsman said.

Cassidy Ward wrote in SYFY: There’s also evidence that burial wasn’t necessarily permanent. Researchers found indications that bones were sometimes removed from the grave and kept in the community for a time. They’d be passed around and these secondary or tertiary funeral rituals often included the painting of houses and addition of pigment to the remains or the burial site. The fact that these activities were not evenly distributed across individuals might be an early example of social inequality which evolved over time until it reached its modern form.

Catalhoyuk Dwellings

A typical Catalhoyuk house was 29-by-20-feet and contained a 20-by-20-foot room and a smaller chamber divided into two subrooms. The floors were plastered and platforms were built in the large room. Many dwellings contained a burial platform under which people (presumably family members) were buried. One of the small rooms had an oven which was used make meals with lentils and grain. To get in the houses people had walk down a ladder from an opening in the roof.

It is believed each building was occupied by a family with five to ten members. Hodder believes the main room was “the locus of family living, cooking, eating, craft activities, and sleeping.” The side rooms were used mainly “for storage and food preparation.” Few houses share walls — even ones right next to each other. Each house was built of bricks of distinct composition or shape.

The interior walls were made of mud brick covered by plaster, often multiple layers of it, on which sometimes murals were painted. Benches and platforms were constructed with plaster. Many of these were constructed of multiple layers of plaster, with base coat and thinner overlying finished coats. The walls were windowless and tended to be about 40 centimeters thick and 2.8 to 3.2 meters high. But even without windows the rooms could be quite bright in the middle of the day when light shined down from overhead through the roof-top door and reflected off the plaster walls.

Rooms, Furniture and Living in a Çatalhöyük House

Each house seemed to have its own hearth (set away from the walls) , domed oven (set into the walls), obsidian caches, storage rooms, and work rooms. Depressions for holding pots and other small stores were built below the floor. The bins in the houses suggest they all had similar storage capacity for agricultural produce. Furnishings in the main room included reed matting, three platforms, a plastered tomb post, an oven and stairs to the roof. Storage bins were situated in one small square-shaped room. In a longer adjacent room were an oven and a food basin. Arched doorways connected the rooms. They only way out of the house was via the stairway to the roof. It is believed the stairs were made of logs with steps notched into them.

Cristina Belmonte wrote in National Geographic History: Built back-to-back, people entered their homes through an opening in the roof. They climbed down a ladder to the main room. The oven and hearth were positioned below the entrance, which also served as a vent for smoke. Inhabitants cooked food in this part of the main room. The floors were blackened with ash and soot. Obsidian, highly prized for its smooth finish, was fashioned in this room and used to create numerous objects, including mirrors. Archaeologists also found that infants and newborns were buried in this part of the home. [Source: Cristina Belmonte, National Geographic History, March 27, 2019]

Benches or platforms separated the “clean” part of the house from the dirty. The floors were free from the blackening caused by fire. It appears they were also plastered more frequently. These clean spaces were where youths and adults were buried. Later excavations at the site revealed the emphasis the residents placed on hygiene: Garbage was burned, buried, and covered with ash, a general cleanliness that may explain why forensic tests have revealed that the population was remarkably healthy. The walls in these clean spaces were also a focal point for art.

restoration of a room

Construction and Rebuilding of the Catalhoyuk Dwellings

Building materials such as plaster and mud were also readily available near the Catalhoyuk settlement itself. Hodder wrote in Natural History magazine, “Once a year — in some cases once a month — floors and wall plates had to be resurfaced. Those thin layers of plaster, somewhat like the growth rings in a tree, trap traces of activity in a well-defined temporal sequence...The floors even preserve such subtle tokens of daily life as the impressions of floor mats. Maddens are just as finely layered, making it possible to identify details as subtle as individual dumps of trash from a hearth. When a house reached the end of its practical life, people demolished the upped walls and carefully filled in the lower half of the house, which then became the foundation of a new house. The mound itself came into being largely through such gradual accumulation. Taking it apart enable users to revisit the past.”

Hodder said that when houses were rebuilt a meticulous procedure was followed: “Workers first cleaned and scoured the walls and plaster features of the original house. They removed the roof, took out the main support posts, and dismantled the walls, usually down to a height of three or four feet. Fixtures such as ovens and decorative and ritual elements were often removed or truncated. The old house was then filled with a mixture of building materials, often very carefully...New excavation show how the inhabitants of Catalhoyuk were always tinkering with internal details of the homes....There were continual adjustments in the course of daily life, the spaces ere remade, reworked, moved and used for different purposes.”

Cristina Belmonte wrote in National Geographic History: To date, no monumental constructions (temples, grand communal buildings, or burial grounds) have been found at Çatalhöyük. Archaeologists believe this lack suggests a remarkably egalitarian society — at least in its earlier stages. Some buildings with more burials and more elaborate architecture have been identified, notable for the presence of bull’s horns on pedestals or other elements. However, the people who lived in these homes did not control food production, nor were their burials more elaborate than others. It is thought they served to keep the historical and cultural memory of the community alive. Hodder’s team dubbed these buildings “history houses.” [Source: Cristina Belmonte, National Geographic History, March 27, 2019]

Catalhoyuk Art

Cristina Belmonte wrote in National Geographic History: The walls in these clean spaces were also a focal point for art. The artworks were typically painted in red or black pigments and feature geometric motifs, human hands, and wild animals. The relationship with these animals must have been a powerful element of local beliefs. Leopards, boars, and bears are all depicted. Perhaps the most important of all was the wild bull, whose horns were placed on platforms or in other parts of the home. [Source: Cristina Belmonte, National Geographic History, March 27, 2019]

Some murals at Çatalhöyük depict the relationship between wild animals and people. In one energetic painting animals flee from hunters. Other murals show the animals fighting with each other. There is own image of the two cheetahs in combat. Dwellings contained murals and plaster reliefs of erupting volcanoes, men hunting aurochs (ancient cattle) and deer, men pulling the tails and tongues of aurochs and stags, men vaulting on the backs of animals, vultures eating headless people and leopards with female figures thought to represent goddesses. There are also painted plaster reliefs of stags, bulls, human females and leopards colliding like rams. One mural with leopards is regarded as the world's oldest mural. It dates to 6200 B.C. One wall painting was found in the southern part of Çatalhöyük with a variety of marks and symbols. Researchers have said interpreting what drawings mean is very difficult.

One wall painting discovered in the 1960s by Mellaart appears to depict an ancient town, perhaps Catalhoyuk itself, with a twin-peaked volcano erupting in the background which archaeologists believe is Hasan Dag. Hodder wrote: “What particularly fascinates me are the many leopard motifs, including reliefs of paired leopards, the images suggesting relationships with wild animals was a potent element in local religious ritual and belief, In line with that interpretation, the household shrines often incorporated the horns of a wild bull.”

In addition to wall paintings the people of Çatalhöyük constructed enigmatic figurines. An unfinished figurine from called the “Bearded Man” appears to represent a reclining man. It was found in Çatalhöyük in 2009. The people of Çatalhöyük were some of the earliest potters in the world.

Bull skulls have been found molded into the walls and floors. Describing a mural in one room with ten painted men, Orrin Shane and Mine Kucuk write in Archaeology magazine, “The fragmentary images appeared to be geometric figures and floral designs. Pieces of horn and antler set in the...wall plaster indicated that this wall had a plaster relief.”

According to National Geographic History: Mellaart unearthed corpulent figures that he believed were powerful symbols of fertility. The most famous of these is a clay sculpture of a voluptuous woman, perhaps in the midst of giving birth. Her hands rest on the heads of two leopards, whose tails are coiled around her shoulders. When it was uncovered, a leopard’s head and the woman’s head and right hand were all missing. They have been reconstructed. See Religion Above [Source: Cristina Belmonte, National Geographic History, March 27, 2019]

Çatalhöyük Diet and Food

Analysis of proteins preserved in bowls, pottery and jars at Çatalhöyük has revealed what the people there ate. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the Freie Universität Berlin and the University of York using this method have provided glimpses of the diet of people living at the site in astonishing scope and detail, determining that vessels from this early farming site contained cereals, legumes, dairy products and meat, in some cases narrowing food items down to specific species. [Source: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, October 3, 2018]

According to the Max Planck Institute: For this study, the researchers analyzed vessel sherds from the West Mound of Çatalhöyük, dating to a narrow timeframe of 5900-5800 B.C. towards the end of the site's occupation. The vessel sherds analyzed came from open bowls and jars, as shown by reconstructions and had calcified residues on the inside surfaces. In this region today, limescale residue on the inside of cooking pots is very common. The researchers used state-of-the-art protein analyses on samples taken from various parts of the ceramics, including the residue deposits, to determine what the vessels held.

The analysis revealed that the vessels contained grains, legumes, meat and dairy products. The dairy products were shown to have come mostly from sheep and goats, and also from the bovine (cattle) family. While bones from these animals are found across the site and earlier lipid analyses have identified milk fats in vessels, this is the first time researchers have been able to identify which animals were actually being used for their milk. In line with the plant remains found, the cereals included barley and wheat, and the legumes included peas and vetches. The non-dairy animal products, which might have included meat and blood, came primarily from the goat and sheep family, and in some cases from bovines and deer. Interestingly, many of the pots contain evidence of multiple food types in a single vessel, suggesting that the residents mixed foods in their cuisine, potentially as porridges or soups, or that some vessels were used sequentially for different food items, or both.

One particular vessel however, a jar, only had evidence for dairy products, in the form of proteins found in the whey portion of milk. "This is particularly interesting because it suggests that the residents may have been using dairy production methods that separated fresh milk into curds and whey. It also suggests that they had a special vessel for holding the whey afterwards, meaning that they used the whey for additional purposes after the curd was separated," states Jessica Hendy, lead author, of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. These results show that dairying has been ongoing in this area since at least the 6th millennium B.C., and that people used the milk of multiple difference species of animal, including cow, sheep and goat.

However, the researchers emphasize that based on the archaeological record an even greater variety of foods, especially plant foods, were likely eaten at Çatalhöyük, which either were not contained in the vessels they studied or are not present in the databases they use to identify proteins. The "shotgun" proteomic approaches used by the researchers are heavily dependent on reference sequence databases, and many plant species are not represented or have limited representation. "For example, there are only 6 protein sequences for vetch in the databases. For wheat, there are almost 145,000," explains Hendy. "An important aspect of future work will need to be expanding these databases with more reference sequences."

“World’s Oldest Bread” — 8,600 Years Old Found in Çatalhöyük

In April 2014, archaeologists announced that they had discover what may be oldest known piece of bread at Çatalhöyük — dating back to around 6,600 B.C. The Independent reported: In a new excavation at the site, researchers have uncovered the remains of a building with what appears to be an ancient oven surrounded by wheat, barley, and pea seeds. Archaeologists also found a “spongy” organic residue near the oven with the mark of a finger pressed at its center. The earliest known evidence of fermented bread before this discovery was from ancient Egypt around 1,500 B.C..[Source: Vishwam Sankaran, The Independent, April 17, 2024]

According to CNN: A largely destroyed oven structure was found in an area called “Mekan 66,” where there are adjoining mudbrick houses. Analyses determined that the organic residue around the oven was 8,600-year-old, uncooked, fermented bread. “We can say that this find at Çatalhöyük is the oldest bread in the world,” archeologist Ali Umut Türkcan, head of the Excavation Delegation and an associate professor at Anadolu University in Turkey, told Turkish state news outlet Anadolu Agency. [Source: Amarachi Orie and Gul Tuysuz, CNN, March 9, 2024]

“It is a smaller version of a loaf of bread...It has not been baked, but it has been fermented and has survived to the present day with the starches inside. There is no similar example of something like this to date,” he added. Scanning electron microscope images showed air spaces in the sample, with the sighting of starch grains “eliminating our suspicions,” biologist Salih Kavak, a lecturer at Gaziantep University in Turkey, said in the release. He added that analyses uncovered chemicals found in plants and indicators of fermentation. Flour and water had been mixed in, with the bread having been prepared next to the oven and kept for a while. “The fact that the building was covered with fine clay has allowed both wood and bread to be stored to this day,” Türkcan said. “It is an exciting discovery for Turkey and the world,” Kavak said.

As Çatalhöyük People Became More Urbanized Their Living Conditions Because Dirtier

The population at Çatalhöyük peak at around 8,000 in 6,500 B.C but after a rapid decline it was abandoned just over 500 years later, in 5950 B.C. Scientists have long wondered why this occurred. Çatalhöyük grew and its population increased as its inhabitants transitioned from foraging to farming. In a study published in the journal PNAS in June 2019 scientists found that movements towards agriculture and urbanization were accompanied by increases in filth and disease. [Source: Newsweek, June 17, 2019]

Newsweek reported: To understand the social changes that took place at Çatalhöyük, researchers, led by Clark Spencer Larsen of The Ohio State University, looked at the remains of 749 individuals from a broad demographic from the neonatal to the elderly. By looking at changes to the skeletons over the period of occupation, the team was able to deduce certain changes that took place. "Çatalhöyük was one of the first proto-urban communities in the world and the residents experienced what happens when you put many people together in a small area for an extended time," Larsen said in a statement.

The team discovered the population expanded rapidly during the Middle Period (6700−6500 B.C). Analysis of the mud houses shows that at its population peak, residents were experiencing extreme overcrowding. Residential dwellings were built like apartments and they could only be accessed by the roof, via ladders. The walls of the houses were found to have traces of animal and human fecal matter: "They are living in very crowded conditions, with trash pits and animal pens right next to some of their homes. So there is a whole host of sanitation issues that could contribute to the spread of infectious diseases," Larsen said.

Residents kept sheep and goats — the former of which is host to several human parasites. Living in close quarters in extremely cramped conditions could have contributed to public health problems — about a third of residents were living with infections in their bones, analysis revealed.

As Çatalhöyük People Became More Urbanized They Also More Violent

In the 2019 a study PNAS scientists also discussed how the movements towards agriculture and urbanization were accompanied by increases in interpersonal violence.According to Newsweek: The team also found an increase in violence. Of 93 skulls in the sample, over a quarter were found to have suffered from fractures. The shape of the injury suggests people were hit over the head with hard round objects — potentially clay balls that were also discovered at the site. Over half of the victims were women and many of the blows appear to have been inflicted when the victims were facing away from their attacker. [Source: Newsweek, June 17, 2019]

Researchers believe the increase in violence coincides with the changes to the population size: "An argument can be made for elevated stress and conflict within the community," they wrote. "This finding matches those from a number of settings today and in the archaeological past, confirming the association between violence and demographic pressure."

Larsen believes understanding what happened at Çatalhöyük could help with the challenges we face today, as the population increases and our cities get even more overcrowded. "We can learn about the immediate origins of our lives today, how we are organized into communities. Many of the challenges we have today are the same ones they had in Çatalhöyük — only magnified," he said.

All this may tie into why Çatalhöyük collapsed. Cristina Belmonte wrote in National Geographic History: Evidence suggests that the social system gradually broke down due to cultural shifts and climate change. In the later period, archaeologists detected an increase in the differences dividing social classes. Homes were no longer the center of ritual and social relations and became centers of production and consumption. [Source: Cristina Belmonte, National Geographic History, March 27, 2019]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, except Boncuklu Höyük, Archaeology News

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024