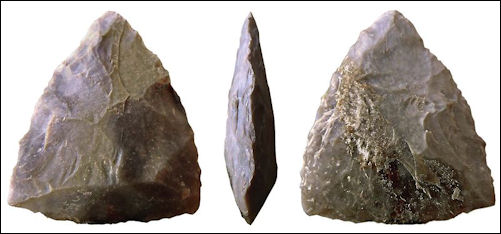

EARLY MODERN HUMAN TOOLS

hand ax Modern humans that lived in Blombos Cave near Capetown, South Africa 80,000 to 95,000 years ago used bone tools and sophisticated pressure-flaked points — made from stones brought more than 25 miles away — to drill holes in ocher, possibly to extract pigments to cover their faces or bodies for ritual purposes. Scientists also found bones from large fish in Blombos Cave which they believed may have been lured to an area with bait and then speared with bone points tied to wooden shafts.

Modern human tools included bone needles, fish hooks, harpoons, antler batons, and a wide assortment of scrapers, knives and engravers. Archaeological evidence from 30,000 to 10,000 B.C. shows that our ancestors were able to fracture, chip and shape rocks into a number of useful tools; use stone awls and burins (incising tools) to make barbed bone and antler harpoon points, atlatl throwing boards for spears and animal bone needles used for making animal-skin clothing.

Modern humans learned that flint heated to temperatures of 400 to 1100 degrees F and cooled slowly became more elastic and easier to work. Harpoons found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formally Zaire) were used to hunt giant catfish. They were made from bones ground to sharp points and notched with triangular teeth to grab on to slippery fish. Circular grooves to the tail helped to fasten the harpoons on sticks.

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RELATED ARTICLES: TYPES OF EARLY MODERN HUMAN TOOLS europe.factsanddetails.com ; OTZI, THE ICEMAN: HIS APPEARANCE, HOME, BACKGROUND, DNA AND TOOLS europe.factsanddetails.com ; NEANDERTHAL TOOLS: MATERIALS, GLUE, STRING AND INTELLIGENCE europe.factsanddetails.com ; TOOLS FROM THE EARLY HOMO PERIOD factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Stone Tools in Human Evolution”

by John J. Shea (2016) Amazon.com;

“Flintknapping: Making and Understanding Stone Tools”

by John C. Whittaker (1994) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe” by André Debénath, et al. Amazon.com

“Prehistoric Stone Tools of Eastern Africa: A Guide” by John J. Shea Amazon.com;

“Understanding Middle Palaeolithic Asymmetric Stone Tool Design and Use: Functional Analysis and Controlled Experiments to Assess Neanderthal” by Lisa Schunk Amazon.com;

“The Emergence of the Acheulean in East Africa and Beyond” by Rosalia Gallotti, Margherita Mussi Editors, (2018) Amazon.com;

” Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide” by John J. Shea Amazon.com;

“Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis” (Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology)

by William Andrefsky Jr (2006) Amazon.com;

“Lithic Analysis (Manuals in Archaeological Method, Theory and Technique)”

by George H. Odell (2004) Amazon.com;

Middle Paleolithic Tool Technologies

According to the University of California at Santa Barbara: “The most important point to remember about the Middle Paleolithic (about 200,000 years ago to about 40,000 years ago) stone technologies is that the emphasis shifted from core tools, like the Acheulean Handaxe, to flake tools like the Levallois point. Certainly, even at Olduvai, hominids had been taking advantage of sharp-edged flakes and even modifying them for specific tasks. The important difference in the Middle Paleolithic is that cores were being carefully shaped to produce flakes of a predetermined size and shape. The flakes were then further modified into both simple and complex tools. The two main stone tool technologies were: 1) The Levallois Technique (See Mousterian Tools) and 2) The Disk Core Technique. [Source: University of California at Santa Barbara =|=]

Neanderthal Mousterian tool

“The Disk Core Technique is not significantly different from the Levallois Technique (See Below). The technology still depends on careful core shaping and preparation in order to remove ready-to-use flakes for tools. The principal difference in the Disk Core Technique is that even more refinement and skill went into the core preparation so that more flakes could be removed from one core. Thus, the Disk Core technique is really a refinement of trends started by the Levallois technique. The exhausted cores left behind by this process often look like small disks with multiple flake scars, hence the name. =|=

“The most important thing to note about the Disk Core Technique is its efficiency. Using this technique a skilled flinknapper could produce many more usable tools from a single piece of raw material than was possible using any of the other techniques previously discussed. The process you have just seen would then be repeated, first working the other side of the core, then trimming off the rough top and bottom flake scars, perhaps removing tool flakes from the opposite end of the core. Three to five tools could probably be manufactured from a core this size by a skilled craftsman. Eventually, of course, the core would become too small and thin to produce more tools and would be discarded. This final exhausted discoidal form is all the evidence that we have of this remarkable improvement in the efficiency of lithic technology attained by Neanderthals and archaic Homo sapiens.” =|=

Pressure Flaking Invented 75,000 in Africa, Not 20,000 Years Ago in Europe

A highly-skilled tool-making technique that shapes stones into sharp-edged tools was thought to have originated in Europe 20,000 years ago but in fact appears to have been invented by Africans some 75,000 years ago. The technique known as pressure-flaking involves using an animal bone or some other object to exert pressure near the edge of a stone piece and precisely carve out a small flake. Stone tools shaped by hard stone hammer strikes and then struck with softer strikes from wood or bone hammers. Edges are carefully trimmed by directly pressing the point of a tool made of bone on the stone. [Source: Discovery.com, Reuters, October 28, 2010 |~|]

Discovery.com reported: “Researchers from the University of Colorado at Boulder examined stone tools dating from the Middle Stone Age, some 75,000 years ago, from Blombos Cave in what is now South Africa. The team found that the tools had been made by pressure flaking, whereby a toolmaker would typically first strike a stone with hammer-like tools to give the piece its initial shape, and then refine the blade’s edges and shape its tip. |~|

“The technique provides a better means of controlling the sharpness, thickness and overall shape of two-sided tools like spearheads and stone knives, said Paola Villa, a curator at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History and a co-author of the study published in the journal Science. “Using the pressure flaking technique required strong hands and allowed toolmakers to exert a high degree of control on the final shape and thinness that cannot be achieved by percussion,” Villa said. “This control helped to produce narrower and sharper tool tips...These points are very thin, sharp and narrow and possibly penetrated the bodies of animals better than that of other tools.” |~|

“To arrive at their conclusion that prehistoric Africans could have been the first to use pressure flaking to make tools, the researchers compared stone points, believed to be spearheads, made of silcrete — quartz grains cemented by silica — from Blombos Cave, and compared them to points that they made themselves by heating and pressure-flaking silcrete collected at the same site. |~|

“The similarities between the ancient points and modern replicas led the scientists to conclude that many of the artifacts from Blombos Cave were made by pressure flaking, which scientists previously thought dated from the Upper Paleolithic Solutrean culture in France and Spain, roughly 20,000 years ago. “Using the pressure flaking technique required strong hands and allowed toolmakers to exert a high degree of control on the final shape and thinness that cannot be achieved by percussion,” Villa said. “This finding is important because it shows that modern humans in South Africa had a sophisticated repertoire of tool-making techniques at a very early time.” The authors speculated that pressure flaking may have been invented in Africa and only later adopted in Europe, Australia and North America.” |~|

The co-authors included Vincent Mourre of the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research and Christopher Henshilwood of the University of Bergen in Norway and director of the Blombos Cave excavation. “This flexible approach to technology may have conferred an advantage to the groups of Homo sapiens who migrated out of Africa about 60,000 years ago,” the authors wrote in Science. |~|

Mousterian tool

Africans Made Microliths 71,000 Years Ago, Earlier Than Thought

In 2012, paleontologists announced that they had found small blades in a South African cave proving that man was an advanced thinker making stone tools 71,000 years ago, thousands of years earlier than thought, and the capacity for complex thought and weapons production gave modern humans an evolutionary advantage over Neanderthals, researchers said in a study published in Nature. [Source: AFP, November 8, 2012]

AFP reported: “Small, manufactured blades such as those found in hunting arrows were first thought to have appeared in South Africa between 65,000 and 60,000 years ago. Now, a team of scientists say they have found much older blades, called microliths and produced by chipping away at heat-treated stone, in a cave near Mossel Bay on South Africa's south coast "Our research... shows that microlithic technology originated early in South Africa, evolved over a vast time span (about 11,000 years) and was typically coupled to complex heat treatment," the study authors wrote. "Advanced technologies in Africa were early and enduring," they said, adding that long absences of tool-use evidence in the palaeontological record are explained by the relatively small number of sites excavated to date, not by an ebb and flow in early man's technological know-how.

“The find is evidence that early modern humans in South Africa had the ability to make complex designs and teach others to copy them, said the researchers. This would have allowed them to produce tools like arrows with a much longer killing distance than hand-cast spears. "Microlith-tipped projectile weapons increased hunting success rate, reduced injury from hunting encounters gone wrong, extended the effective range of lethal interpersonal violence," wrote the team.

“It would also have conferred "substantive advantages on modern humans as they left Africa and encountered Neanderthals equipped only with hand-cast spears". Neanderthals lived in parts of Europe, Central Asia and the Middle East for up to 300,000 years but appear to have vanished some 40,000 years ago. In a comment on the study, also published by Nature, anthropologist Sally McBrearty from the University of Connecticut said humans making the monoliths would have chipped small blades from stone carefully selected for its texture and heat-treated to make it easier to work with. They would then have retouched the blades into geometric shapes, probably for use in arrows to be shot from bows. This, in turn, meant the makers would have had to collect other materials such as wood, fibres, feathers, bone and sinew over a period of days, weeks or months, interrupted by other, more urgent tasks. "The ability to hold and manipulate operations and images of objects in memory, and to execute goal-directed procedures over space and time, is termed executive function and is an essential component of the modern mind," McBrearty wrote.

microliths

Small Lethal Tools Gave Early Modern Human an Advantage?

The technology described above allowed projectiles to be thrown greater distances, increasing the killing power of the projectiles while allowing the thrower to be a safe distance away from a potential counter-attack. The key to this advance was the small microlithic blades. According to Arizona State University: “The reported technology focused on the careful production of long, thin blades of stone that were then blunted (called “backing”) on one edge so that they could be glued into slots carved in wood or bone. This created light armaments for use as projectiles, either as arrows in bow and arrow technology, or more likely as spear throwers (atlatls). These provide a significant advantage over hand cast spears, so when faced with a fierce buffalo (or competing human), having a projectile weapon of this type increases the killing reach of the hunter and lowers the risk of injury. The stone used to produce these special blades was carefully transformed for easier flaking by a complex process called “heat treatment,” a technological advance also appearing early in coastal South Africa and reported by the same research team in 2009. [Source: Arizona State University, November 7, 2012]

“Good things come in small packages,” said Kyle Brown, a skilled stone tool replicator and co-author on the paper, who is an honorary research associate with the University of Cape Town, South Africa. “When we started to find these very small carefully made tools, we were glad that we had saved and sorted even the smallest of our sieved materials. At sites excavated less carefully, these microliths may have been discarded in the back dirt or never identified in the lab.”

Prior work showed that this microlithic technology appear briefly between 65,000 and 60,000 years ago during a worldwide glacial phase, and then it was thought to vanish, thus showing what many scientists have come to accept as a “flickering” pattern of advanced technologies in Africa. The so-called flickering nature of the pattern was thought to result from small populations struggling during harsh climate phases, inventing technologies, and then losing them due to chance occurrences wiping out the artisans with the special knowledge. “Eleven thousand years of continuity is, in reality, an almost unimaginable time span for people to consistently make tools the same way,” said Marean. “This is certainly not a flickering pattern.”

Research on stone tools and Neanderthal anatomy strongly suggests that Neanderthals lacked true projectile weapons. “When Africans left Africa and entered Neanderthal territory they had projectiles with greater killing reach, and these early moderns probably also had higher levels of pro-social (hyper-cooperative) behavior. These two traits were a knockout punch. Combine them, as modern humans did and still do, and no prey or competitor is safe,” said Marean. “This probably laid the foundation for the expansion out of Africa of modern humans and the extinction of many prey as well as our sister species such as Neanderthals.”

Climate Change Spurred Tool Development in Middle Stone Age Africa?

Bifacial points found in Blombos Cave, South Africa, were manufactured 75,000 years ago by modern humans. Scientists suggest they developed these tools during a period when the climate was warmer and wetter and this had role in the points development. Geoffrey Mohan wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “A rapid shift in climate that brought wetter and warmer conditions in southern Africa during the Middle Stone Age helped propel innovation and cultural advances in early man, a study has found. Paleontologists have long known that anatomically modern human’s technological progress moved in fits and starts in various regions of the planet. [Source: Geoffrey Mohan, Los Angeles Times, May 21, 2013 \=]

“A European team suggests that one period of abrupt change, about 40,000-80,000 years ago in what now is South Africa, matches with a climate shift brought about by cyclical changes in the currents of the Atlantic Ocean. Their findings were published in Nature Communications. A period when the Atlantic no longer drew warm water toward upper latitudes, in a similar fashion to today’s gulf stream, created a colder Northern Hemisphere, a weaker Asian monsoon cycle and a band of temperate climate in South Africa, the team found. \=\

“Around this time, engraving and the manufacture of stone and bone tools and jewelry flourished in several areas of the south African cape, probably because of a climate shift that encouraged population expansion. "The occurrence of several major Middle Stone Age industries fell tightly together with the onset of periods with increased rainfall," said Ian Hall, a paleoclimatologist at Cardiff University in Wales. "When the timing of these rapidly occurring wet pulses was compared with the archaeological data sets, we found remarkable coincidences.” \=\

biface ax

“But as the local south African climate again shifted abruptly toward less rain during a warming in the Northern Hemisphere, innovation came to an apparent halt in one area about 59,000 years ago, and shifted east and north, the researchers found. The team examined about 100,000 years of sediment cores from the mouth of the Great Kei River and matched periods of heavy sediment flow – indicating more rain – with temperature shifts gleaned from studies of Antarctic ice cores. The climate changes and shifting locations of innovation could help explain the prevailing theory that anatomically modern humans migrated from Africa, eventually replacing the Northern Hemisphere's Neanderthals.” \=\

Advanced Toolmaking Kickstarted Language?

Some scientists theorize that the brain power that developed hand-in-hand with advanced hand-toolmaking potentially paved the way for language development. Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “The design of stone tools changed dramatically in human pre-history, beginning more than two million years ago with sharp but primitive stone flakes, and culminating in exquisite, finely honed hand axes 500,000 years ago. The development of sophisticated stone tools, including sturdy cutting and sawing edges, is considered a key moment in human evolution, as it set the stage for better nutrition and advanced social behaviours, such as the division of labour and group hunting. "There has been a long discussion in the archaeology community about why it took so long to make more complex stone tools. Did we simply lack the manual dexterity, or were we just not smart enough to think about better techniques?" said Aldo Faisal, a neuroscientist at Imperial College London. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, November 3, 2010 |=|]

“Faisal's team investigated the complexity of hand movements used by an experienced craftsman while he made replicas of simple and then more complex stone tools. Bruce Bradley, an archaeologist at Exeter University, wore a glove fitted with electronic sensors while he chipped away at stones to make a razor-sharp flake and then a more sophisticated hand axe. The results showed that the movements needed to make a hand axe were no more difficult than those used to make a primitive stone flake, suggesting early humans were limited by brain power rather than manual dexterity. |=|

“Early humans were adept at making stone flakes, but these were so thin they were liable to break while being used. The movements needed to make advanced tools were no more difficult, but they had to be executed more intelligently, to produce a tool that had a fat, sturdy body with a sharp cutting edge. |=|

“The oldest and simplest stone tools, known as Oldowan flakes, were uncovered alongside the fossilised remains of Homo habilis, a forerunner of modern humans, in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. Stone hand axes have been uncovered next to bones of Homo erectus, the ancient human species that led the migration out of Africa. Hand axes are usually worked symmetrically on both sides into a teardrop shape. |=|

“Brain scans of modern stone-tool makers show that key areas in the brain's right hemisphere become more active when they switch from making stone flakes to more advanced tools. Intriguingly, some of these brain regions are involved in language processing. "The advance from crude stone tools to elegant handheld axes was a massive technological leap for our early human ancestors. Handheld axes were a more useful tool for defence, hunting and routine work," said Faisal, whose study appears in the journal PLoS ONE. "Our study reinforces the idea that toolmaking and language evolved together as both required more complex thought, making the end of the lower paleolithic a pivotal time in our history. After this period, early humans left Africa and began to colonise other parts of the world." |=|

Bifaz triangular blade

Microblades Linked with Mobile Adaptations in North-Central China

In 2013, Phys.org reported: “Though present before the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, around 24,500–18,300 years ago), microblade technology is uncommon in the lithic assemblages of north-central China until the onset of the Younger Dryas (YD, around 12,900–11,600 years ago). Dr. GAO Xing, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team discussed the origins, antiquity, and function of microblade technology by reviewing the archaeology of three sites with YD microlithic components, Pigeon Mountain (QG3) and Shuidonggou Locality 12 (SDG12) in Ningxia Autonomous Region, and Dadiwan in Gansu Providence, suggesting the rise of microblade technology during Younger Dryas in the north-central China was connected with mobile adaptations organized around hunting, unlike the previous assumption that they served primarily in hunting weaponry. Researchers reported online in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. [Source: Phys.org, June 13, 2013 ==]

“The late Pleistocene featured two severe, cold–dry climatic downturns, the Last Glacial Maximum and Younger Dryas that profoundly affected human adaptation in North China. During the LGM archaeological evidence for human occupation of northern China is scant and North China's earliest blade-based lithic industry, the Early Upper Paleolithic (EUP) flat-faced core-and-blade technology best known from Shuidonggou Locality 1 (SDG1) on the upper Yellow River, was replaced by a bipolar percussion technology better suited to lower quality but more readily available raw material. ==

“Researchers presented evidence that the initial rise in microblade use in North China occurs after 13,000 years ago, during the YD, from three key sites in west-central northern China: Dadiwan, Pigeon Mountain and Shuidonggou Locality 12 (SDG12). In this region composite microblade tools are more commonly knives than points. These data suggest the rise of microblade technology in Younger Dryas north-central China was mainly the result of microblades used as insets in composite knives needed for production of sophisticated cold weather clothing needed for a winter mobile hunting adaptation like the residentially mobile pattern termed ”serial specialist." Limited time and opportunities compressed this production into a very narrow seasonal window, putting a premium on highly streamlined routines to which microblade technology was especially well-suited. ==

“It has been clear for some time that while microblades may have been around in north-central China since at least the LGM, they become prominent (i.e., chipped stone technology becomes ”microlithic”) only much later, with the YD. This sequence suggests a stronger connection between microblades and mobility than between microblades and hunting. If microblades were only (or mainly) for edging weapons, their rise to YD dominance would suggest an equally dramatic rise in hunting, making it difficult to understand why a much more demanding microblade technology would develop to facilitate the much less important pre-YD hunting. In any event, the SDG12 assemblage is at odds with the idea of a hunting shift. No more or less abundant than in pre-YD assemblages (e.g., QG3), formal plant processing tools suggest a continued dietary importance of YD plants, and there is no evidence for hunting of a sort that would require microblade production (i.e., of weaponry insets) on anything like the scale in which they occur. A shift to serial specialist provides a better explanation. ==

“Serial specialists are frequently forced to accomplish significant amounts of craftwork in relatively short periods of time. Microblade technology is admirably suited to such streamlined mass-production, and this is exactly what the SDG12 record indicates. The intensity with which SDG12 was used and the emphasis on communal procurement suggests a fairly short-term occupation by groups that probably operated independently during the rest of the year, almost certainly during the winter. SDG12 was most likely occupied immediately before that in connection with a seasonal ”gearing up” for winter, perhaps equivalent to the ethnographically recorded “sewing camps” of the Copper Inuit and Netsilik Inuit. == Yi Mingjie of the IVPP, one of the authors of the study, said: “Our study indicates that YD hunter-gatherers of north-central China were serial specialists, more winter mobile than their LGM predecessors, because LGM hunter-gatherers lacked the gear needed for frequent winter residential mobility, winter clothing in particular, and microblade or microlithic technology was central to the production of this gear. Along with general climatic amelioration associated with the Holocene, increasing sedentism after 8000 years ago diminished the importance of winter travel and the microlithic technology needed for the manufacture of fitted clothing." ==

Dr. Robert L. Bettinger of the University of California – Davis, another author said: “We do not argue that microblades were not used as weapon insets (clearly they were), or that microblade technology did not originally develop for this purpose (clearly it might have). We merely argue that the YD ascendance of microblade technology in north-central China is the result of its importance in craftwork essential to a highly mobile, serial specialist lifeway, the production of clothing in particular. While microblades were multifunctional, this much is certain: of the very few microblade-edged tools known from north-central China all are knives, none are points. If microblades were mainly for weapons it should be the other way around”,

Did Hominins Practice Recycling?

In 2013, Associated Press reported: “There is mounting evidence that hundreds of thousands of years ago, our prehistoric ancestors learned to recycle the objects they used in their daily lives, say researchers gathered at an international conference in Israel. "For the first time we are revealing the extent of this phenomenon, both in terms of the amount of recycling that went on and the different methods used," said Ran Barkai, an archaeologist and one of the organizers of the four-day gathering at Tel Aviv University” in October 2013. [Source: Associated Press, October 11, 2013 +++]

“Just as today we recycle materials such as paper and plastic to manufacture new items, early hominins would collect discarded or broken tools made of flint and bone to create new utensils, Barkai said. The behavior "appeared at different times, in different places, with different methods according to the context and the availability of raw materials," he told The Associated Press. From caves in Spain and North Africa to sites in Italy and Israel, archaeologists have been finding such recycled tools in recent years. The conference, titled "The Origins of Recycling," gathered nearly 50 scholars from about 10 countries to compare notes and figure out what the phenomenon meant for our ancestors. +++

“Recycling was widespread not only among early humans but among our evolutionary predecessors such as Homo erectus, Neanderthals and other species of hominins that have not yet even been named, Barkai said. Avi Gopher, a Tel Aviv University archaeologist, said the early appearance of recycling highlights its role as a basic survival strategy. While they may not have been driven by concerns over pollution and the environment, hominins shared some of our motivations, he said. "Why do we recycle plastic? To conserve energy and raw materials," Gopher said. "In the same way, if you recycled flint you didn't have to go all the way to the quarry to get more, so you conserved your energy and saved on the material." +++

“Some participants argued that scholars should be cautious to draw parallels between this ancient behavior and the current forms of systematic recycling, driven by mass production and environmental concerns. "It is very useful to think about prehistoric recycling," said Daniel Amick, a professor of anthropology at Chicago's Loyola University. "But I think that when they recycled they did so on an 'ad hoc' basis, when the need arose."” +++

Examples of Hominin Recycling?

According to Associated Press: “Some cases may date as far back as 1.3 million years ago, according to finds in Fuente Nueva, on the shores of a prehistoric lake in southern Spain, said Deborah Barsky, an archaeologist with the University of Tarragona. Here there was only basic reworking of flint and it was hard to tell whether this was really recycling, she said. "I think it was just something you picked up unconsciously and used to make something else," Barsky said. "Only after years and years does this become systematic." [Source: Associated Press, October 11, 2013 +++]

“That started happening about half a million years ago or later, scholars said. For example, a dry pond in Castel di Guido, near Rome, has yielded bone tools used some 300,000 years ago by Neanderthals who hunted or scavenged elephant carcasses there, said Giovanni Boschian, a geologist from the University of Pisa. "We find several levels of reuse and recycling," he said. "The bones were shattered to extract the marrow, then the fragments were shaped into tools, abandoned, and finally reworked to be used again." +++

“At other sites, stone hand-axes and discarded flint flakes would often function as core material to create smaller tools like blades and scrapers. Sometimes hominins found a use even for the tiny flakes that flew off the stone during the knapping process. At Qesem cave, a site near Tel Aviv dating back to between 200,000 and 420,000 years ago, Gopher and Barkai uncovered flint chips that had been reshaped into small blades to cut meat - a primitive form of cutlery. Some 10 percent of the tools found at the site were recycled in some way, Gopher said. "It was not an occasional behavior; it was part of the way they did things, part of their way of life," he said. +++

“He said scientists have various ways to determine if a tool was recycled. They can find direct evidence of retouching and reuse, or they can look at the object's patina - a progressive discoloration that occurs once stone is exposed to the elements. Differences in the patina indicate that a fresh layer of material was exposed hundreds or thousands of years after the tool's first incarnation.” +++

Did Hominins Practice Tool Recycling for Sentimental Reasons?

In March 2022 study published in the journal Scientific Reports, a team led by archaeologist Bar Efrati at Tel Aviv University examined flint tools crafted by hominins between 300,000 and 500,000 years ago and found that ancient humans frequently recovered, restored, and recycled tools made by previous generations — and they did this not for practical reasons but out of nostalgia and sentimentality. [Source: Cassidy Ward, SYFY, March 13, 2022]

Cassidy Ward wrote in SYFY: Scientists have known for a while that flint tools were reworked and reused at different times in the historical record. The best evidence for this behavior is a phenomenon known as double patina which, when found, clearly demonstrates the refashioning of the same piece of flint over time. “In the case of flint, it basically creates a colorful layer which is different in texture, shine, and color from the actual color of the flint. It’s caused by sun exposure, running water, the properties of the flint itself, and the sediment it’s buried in,” Efrati told SYFY.

After a piece of flint is fashioned into a tool, its surface begins acquiring that patina. It might be used for a time and then discarded as the individual or group using it moves on. Sometime later, it might be found by another group or individual and reshaped. The reshaping process removes the patina in some places, revealing the natural surface of the flint again. When scientists find flint tools today, they can clearly see two distinct patina patterns, indicating that a tool was recycled.

What was previously unclear was why ancient humans were gathering and recycling old tools. One possible reason is pure convenience. Why build a tool from scratch, if there’s a pretty good one sitting in front of you that just needs a little cleaning up? Efrati indicated that convenience likely played a part in why prehistoric humans recycled tools, but probably wasn’t the main reason. Another reason tools might be recycled is if raw materials are in short supply, but that wasn’t the case at the Revadim open-air site on the southern coastal plain of Israel, where this study was carried out. In fact, there is still a robust supply of fresh flint available at the site today. “Revadim was rich with flint,” Efrati said. “Fresh flint was the main way they chose to make their tools. Recycling of old items was happening together with the making of fresh ones, but fresh tools were dominant in terms of quantity.”

The distribution of new versus recycled clearly demonstrates that the people in the area knew how to make new tools, had plenty of raw materials available, and preferred making new tools to recycling old ones. If it was truly more convenient to recycle an old tool then we might expect that to be the dominant form discovered at the site, but that isn’t the case. “There was more than just the function that made them collect and use tools again. The sentimentality, the recognition of someone else making something. They chose to recycle them,” Efrati said.

Researchers also found that recycled tools were minimally reshaped. In most cases, individuals found tools which were already the right size and shape for what they needed, and the modifications were minor. The implication is not only that ancient peoples recognized and appreciated the work of their own ancestors, but they took pains to preserve the initial form of the tools as much as possible.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024