SAHARAN ROCK ART

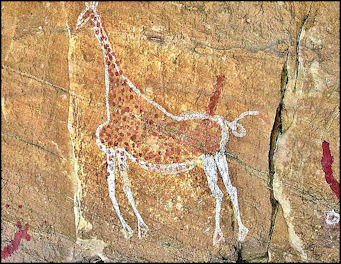

Tadrart Acacus, Libya Extraordinary images of animals and people from time when the Sahara was greener and more like a savannah have been left behind. Engravings of hippos and crocodiles are offered as evidence of a wetter climate. [Source: David Coulson, National Geographic, June 1999; Henri Lhote, National Geographic, August 1987]

Most of the Saharan rock is found in Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Niger and to a lesser extent Egypt, Sudan, Tunisia and some of the Sahel countries. Particularly rich areas include the Air mountains in Niger, the Tassili-n-Ajjer plateau in southeastern Algeria, and the Fezzan region of southwest Libya. Some of the art found in the Sahara region is strikingly similar to rock art found in southern Africa. Scholars debate whether it has links to European prehistoric cave art or is independent of that.

The rock art of Sahara was largely unknown 1957 when French ethnologist Henri Lhote launched a major expedition to Tassili-n-Ajjer. He spent 12 months on the plateau with a team of painters, many of whom were hired by Lhote off the streets in Montmarte in Paris. The painters copied thousands of rock painting, in may cases tracing the outlines on paper and then filling them in with gouache. When the copies were displayed they created quite a stir, especially the images of figures that looked like space aliens. Lhote first visited the area in 1934, traveling from the oasis village of Djanet with a 30 camel caravan.

Geoffrey Blundell of the University of the Witwatersrand wrote: “The art of the Sahara is diverse and still not well understood. Conventionally, the art is believed to broadly fit into one of four stylistic and chronological categories. The earliest of these, known as the Bubaline Period, comprises engravings only, and there are many images of wild animals and therianthropic (part-human, part-animal) figures. The three later periods—Bovidian, Caballine, and Camelline—include both paintings and engravings and are marked by the appearance of specific domestic animals in the art. [Source: Geoffrey Blundell, Origins Centre, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2001 \^/]

“In spite of an initial breakthrough in the understanding of the symbolism of these images in terms of the beliefs and practices of specific extant Saharan peoples in 1966, little further work has been done in using this approach to investigate the meaning of the images. Many new discoveries have been made in recent years; scholars are hopeful that among these a clue to the meaning of some of the images will be found.

Websites and Resources on Prehistoric Art: Chauvet Cave Paintings archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet ; Cave of Lascaux archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en; Trust for African Rock Art (TARA) africanrockart.org; Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com; Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology, by Peter Brown peterbrown-palaeoanthropology.net

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

Books: “Cave Art” by Jean Clottes (Phaidon, 2008); “The Cave Painters” by Gregory Curtis (2006), with interesting insights offer by a non-specialist; “The Nature of Paleolithic Art” by R. Dale Guthrie (2005); “Images of the Past” by Douglas I. Price and Gary M. Feinman (McGraw-Hill, 2006); “The Human Past: World Prehistory & the Development of Human Societies’ edited by Chris Scarre (Thames & Hudson, 2005); “The Dawn of European Art: An Introduction to Palaeolithic Cave Painting” by André Leroi-Gourhan (Cambridge University Press, 1982); “The Origin of Modern Humans” by Roger Lewin (Scientific American Library, 1993).

Contact: Trust for African Rock Art run by David Coulson; Exhibit: Memories of Stone at the Museum of Man in Paris displayed painted copies of the images found in Tassili-n-Ajjir.

Green Sahara

Tadrart Acacus, Libya During the last 300,000 years there have been major periods of alternating wet and dry climates in the Sahara which in many cases were linked to the Ice Age eras when huge glaciers covered much of Europe and North America. Wet periods in the Sahara often occurred when the ice ages were waning. The last major rainy period in the Sahara lasted from about 12,000, when the last Ice Age began to wan in Europe, to 7,000 years ago. Temperatures and rainfall peaked around 9,000 years ago during the so-called Holocene Optimum.

Scientists believed the ice ages and the climate changes in the Sahara were produced by events triggered by changes in the Earth's orbits and rotations based on the fact the timing of the climate changes have correlated with the changes in the Earth’s tilt and rotation. Sometimes when the Earth approached close to the sun or the tilt of the Earth exposed the Northern Hemisphere to more sunlight the African monsoon shifted northward or the Mediterranean winds to shift south.

As the Ice Age in Europe ended more water evaporated from the Atlantic filling clouds and and more moisture was brought to North Africa as monsoon winds from Africa shifted north and Mediterranean westerly winds south because of the cooler temperatures in Europe. This caused the rains that nourished western Africa and the Mediterranean region to move into the Sahara in North Africa.

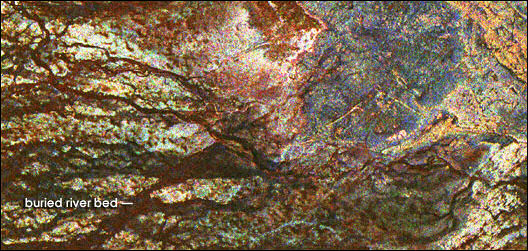

During wet periods in the Sahara oak and cedar trees grew in the highlands and the Sahara itself was a savannah grassland with acacia trees and hackberry trees and shallow lakes and braided rivers. Rock and cave paintings from that time depict abundant wildlife — including elephants and giraffes that lived in the savannahs and hippopotami and crocodiles that lived in the rivers and lakes — and people, who hunted with bows and arrows, herded animals, collected wild grains and fished.

Remnants from the wet periods discovered by scientists include ostrich egg shells, high water marks around lakes that are presently dried up, swamp sediments, pollen from trees and grass and bones of elephants, giraffes, hippopotami, lions, fish, rhinoceros, frogs and crocodiles. Prehistoric inhabitants of Egypt may have raised ostriches. Large numbers of ostrich egg shells have been at excavations at a 9,000-year-old site at Farafra Oasis.

Sahara Becomes a Desert

Beginning around 7,000 years the Sahara began changing from a savannah to a desert. The climates changes in the Sahara occurred in two episodes — the first 6,700 to 5,500 years ago and the second 4,000 to 3,600 years ago. These changed are may have occurred when the African monsoons and Mediterranean winds returned to their normal locations.

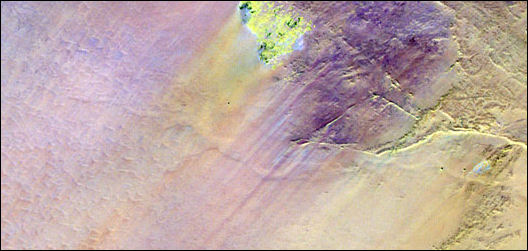

Buried ancient Sahara river near Safsaf Oasis

As the Sahara region dried out grasslands and lakes disappeared. Desiccation occurred relatively quickly, over a few hundred years. Desertification processes were accelerated as vegetation, which helped generate rain, was lost, causing even less rain, and the soil lost its ability to hold moisture when it did rain. Light-colored land without plants reflects rather than absorbs sunlight, producing less warm, moist cloud-forming updrafts, causing even less rain. When it did rain the water washed away or evaporated quickly. The result: desert.

By 2000 B.C. the Sahara was as dry as it is now. The last lake dried up around 1000 B.C. The people that lived in the region were forced to leave and migrate south to find food and water. Some scientist believe some of these people settled on the Nile and became the ancient Egyptians.

Some scientists are currently studying whether global warming could cause the Sahara to bloom again. The current thinking seems to be that yes this is possible but greenhouse gas levels have to increase to a much higher rate than they are at today.

Tassili–n–Ajjer

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Tassili-n-Ajjer in Algeria is one of the most famous North African sites of rock painting. Its imagery documents a verdant Sahara teeming with life that stands in stark contrast to the arid desert the region has since become. Tassili paintings and engravings, like those of other rock art areas in the Sahara, are commonly divided into at least four chronological periods based on style and content. These are: an archaic tradition depicting wild animals whose antiquity is unknown but certainly goes back well before 4500 B.C.; a so-called bovidian tradition, which corresponds to the arrival of cattle in North Africa between 4500 and 4000 B.C.; a "horse" tradition, which corresponds to the appearance of horses in the North African archaeological record from about 2000 B.C. onward; and a "camel" tradition, which emerges around the time of Christ when these animals first appear in North Africa. [Source: Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2000 \^/]

“Engravings of animals such as the extinct giant buffalo are among the earliest works, followed later by paintings in which color is used to depict humans and animals with striking naturalism. In the last period, chariots, shields, and camels appear in the rock paintings. Although close to the Iberian Peninsula, it is currently believed that the rock art of Algeria and Tassili developed independently of that in Europe.

Buried ancient Sahara river near Safsaf Oasis

“While these traditions are successive, it does appear that earlier ones continued on for varying lengths of time after the appearance of later ones. Two important qualifiers need to be made. First, many scholars have recently questioned a pan-Saharan chronology and there is a move away from grandiose chronological schemes to concentrating more on understanding regional chronological variability. Second, the Sahara, given its vast size and various political complications, is still an inadequately researched area in terms of rock art and very few dates exist. As more work is done and techniques for dating advance, it is likely that this four-period dating scheme will be modified in particular regions and that more will be learned about the origins and demise of Saharan rock art. \^/

Painting and Engravings in Saharan Rock Art

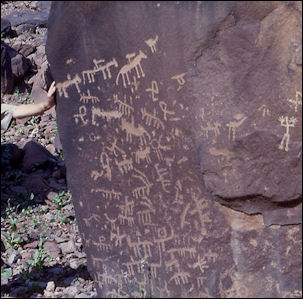

There are several distinct styles of rock art. Most are engravings into stone; some are paintings. Most of the inscribing was done by chiseling away stone. In some places artists made images by chipping away the patina that cover rock, so the image was reveled on the rock itself. The chiseling was done with stone chisels that were hammered from stone tools. Such chisels have been found near inscriptions and were presumably used to make them. Some of the chiseled grooves are more than two inches deep which has helped them endure in the face of desert sandstorms and winds.

Paints were usually made from locally collected minerals such as ocher (red and yellow iron oxide), white clay and charcoal. Blood, fat and urine may have been used as binders. In many cases the colors are still vibrant after millennia of exposure to desert heat. The look better when wet but the moisture damages them. The paints were sometimes applied with brushes made with feathers or animal hair.

Animals in Saharan Rock Art

Old painting were often erased to make way for new paintings. Sometimes new paintings were superimposed on top of old ones. Scientists using infrared detection devices have counted up to 12 superimposed layers painted during a period of around 2,000 years at individual sites. It is not known why certain location were selected for multiple paintings. Perhaps the sites had religious significance or maybe their surfaces and light were particularly good.

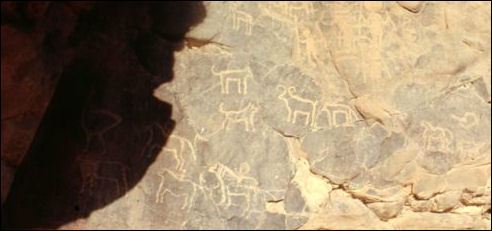

Among the animals depicted are gazelles, elephants, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, wild Barbary sheep, antelope, giraffes, and prehistoric wild oxen (“Babalus antiquus”). Surprisingly there aren’t any lions. The earliest art appeared about 12,000 years ago. The art from 12,000 years ago to 9,000 years ago is called Babulus period art after the wild oxen. Most of images from this period are of large animals hunted by humans.

Among the most beautiful and expertly rendered images are a pair of life-size giraffes carved into stone around 5000 B.C. in central Niger. The rock art authority Jean Clottes described them as a “a world class masterpiece” that deserved to be in the Louvre. The spots of the giraffes are exquisitely rendered. String leaders from the muzzles of each giraffe to cat-size images of people has led some to wonder if ancient people domesticate giraffes.

A group of more than a dozen six- to seven-foot-tall giraffes was rendered on a cliff face in Libya. They too date back to around 5000 B.C. One scholar said they conveyed “a tremendous feeling of a herd on the move.” Images of hippopotami up to five times larger than life size and images of mother and baby hippos have been found. Bones of hippos dated to the same period the painting were made have been found in the dry riverbed of the Tafassassey River, which once flowed south into Lake Chad.

Gravure Rupestre, Algeria

Roundhead Period of Saharan Rock Art

Describing a 7500-year-old work calls the “Crying Cows” in Tassili-n-Ajjer in Algeria, David Coulson wrote in National Geographic: “I was stunned by its almost Piccasoan sophistication. The cattle seem to emerge, horns first, from the rock face...The artist chose his canvas carefully, looking for a surface that would catch the sun’s rays and create depth and the illusion of motion through shadow. At the right time of the year, as the light plays across this engraving, you can almost see the cattle move.”

The first human figures in Saharan art were depicted around 9,000 ears ago. This marks the beginning of the Round Head period which overlaps with the late Babalus period and the early Pastoral period. Human figures from this period tend to have rounded heads and featureless faces. The figures range in size from a few centimeters to five meters in height.

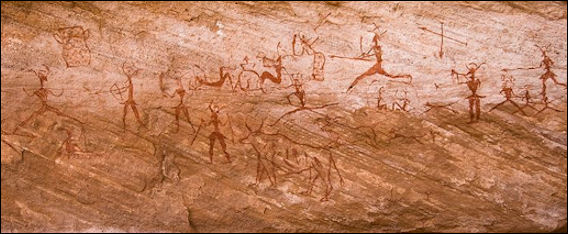

Roundhead Period people are shown standing among cattle, hunting with bows, and dancing with masks on their heads. There are many images of running archers in which the strings of their bows and the leg muscles are visible. Pieces that seem to represent some kind of shamanistic experience depict round-headed people floating towards a figure that seems to be a shaman. There are also scenes of everyday life such as people washing the hair. Images of boats have been found in the Nile Valley and the Red Sea hills.

An 8,000-year-old rock paintings in the Tassil-n-Ajjer depicts dancers and musicians. One of the instruments pictured is still played thousands of miles south in the Kalihari. Seven-thousand-year-old cave painting in the Sahara seem to depict bows being used as musical instrument. Bushmen today make haunting music with bow instruments that are placed in the mouth. Sound is produced by tapping a sinew string with a reed.

One painting from Tassili-n-Ajjer dubbed the elephant dance depicts a line of figures connected by a rope or cord. They men wear hip-high white leggings, reminiscent of grass costumes worn in West Africa, and appear to be engaged in some ritual or ceremony.

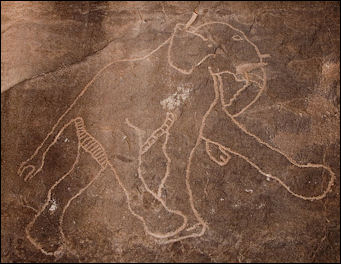

Bizarre Images from the Roundhead Period

Tifinagh Algeria Some of the human-like figures from the Roundhead period are quite bizarre. A well-preserved 4½ foot-high, 8,000-year-old engraving of a mythical beast found in Libya features two mythical catlike creatures engaged in a ritual dance or a battle. Figures, dated to be 2,500 years old, found on boulders in the Air mountains of Niger have tulip-shaped heads and hourglass bodies. Nine-foot-high figures found in the Ennedi mountains of Chad had round heads, enormous buttocks and geometric patterns inscribed on every inch of their body.

Other Roundhead period images include a 10-foot-high horned “god” with bulging biceps and huge scrotum. Next to him is a supplicating woman. One 7000-year-old work depicts a masked figure with plants sprouting from his arms and thighs. Some regard it as the oldest record of the cult of the mask. The masks itself looks very much like masks widely seen in West Africa today.

Pastoral Period of Saharan Rock Art

Around 7,000 years ago domesticated animals began appearing in Saharan rock art. This marked the beginning of the Pastoral Period. The works from this period have a more naturalistic style and depict scenes from everyday life. They are presumed to have been made by herders. The works have more details and appear to express concerns about composition. Rock art specialist Alex Campbell told National Geographic that paintings form this period “started to show man as above nature, rather than as part of nature, seeking its help.”

Tadrart Acacus Libya Images from the Pastoral Period seem to suggest that black people lived in the Sahara at that time. Black people, some of whom wear garments and adornments and have hairdos like some current tribal groups in Africa, are often shown among herds of cattle . Some show men riding n bulls. There are also scenes of couples making love and women carrying children on their backs.

One image from Tassili-n-Ajjer seems to depict help from the spirit world being sought with animal magic. A member of the Fulani tribe that still conduct similar rituals told National Geographic: “The spirit of the earth assumes the shape of the snake goddess, Tyanaba, protector of cattle. Curved lines represent the serpent as she encircles a sacred bull. A man, second from the right joins four women....At the far right, the “mistress of milk” reclines to chant to the earth. She implores that the goddess lift the bulls’ bewitchment — perhaps an illness — and ensure propagation of the herd. The woman third from the left listens for the earth’s response.”

Among the early depictions of war is a battle scene, in a rock painting in Tassili n’Ajjer. dated to between 4300 and 2500 B.C., with groups of men firing bows and arrows at each other. In the image a group on the right stand ready to fire their bows as a group on the left begins an assault.

Horse and Camel Period of Saharan Rock Art

Mauritania The arrival of the horse in the region around 1650 B.C. inaugurated the Horse period. The arrival of the camel around 200 B.C. inaugurated the Camel period and is seen as indicator that Sahara was drying out and becoming the Sahara as we know it and a desert so dry it could no longer support horses.

Images from the Horse period include hunters in chariots, carrying weapons in one hand and holding reigns in the other hand, being chased by a dog. Some scholars regard these hunters as a the People of the Sea, a mysterious group with bronze weapons and armor that unsuccessfully attacked Egypt before retreating into the desert where they assimilated with the indigenous Garamantes, later described by Herodotus as “very powerful people” who rode four-horse chariots and chased black cave dwellers “like the screeching of bats.”

Many images from the Camel period have a childlike quality. The camels in these images are sometimes ridden by riders who ride on saddles covered by a linen framework called a “basour” that provided the riders with some sun protection.

People Who Made the Saharan Rock Art

Little is known about the artists that created the Saharan art work. They may be ancestors of people that still roam the desert or they may be ancestors of people that live today in the Sahel or areas further south in Africa. The long hairdos of some rock art figures found in Libya are similar to those of the modern Wodaadbe people of Niger. Body decorations found on rock art images in Chad resemble body art that found in the Surma of southern Ethiopia today.

When the Sahara dried out the people that lived there migrated southward. Rock art found in southern Africa that is similar to that found in the Sahara is thought to have been introduced there by herdsman originally from North Africa who migrated southward over the generations until they reached southern Africa.

Bushmen paintings in southern Africa and the Bushmen themselves have been studied for insight into the art and artists.

Threats and Efforts to Save Saharan Rock Art

Mauritania Threats to Saharan rock include tourists who wet paintings to make them easier to photographs, insurgents who take refuge in caves and use the art for target practice and looters who use chisels, sledgehammers, chain saws, jackhammers and crowbars to try and pry the works loose, often destroying them or at least badly damaging them in the process.

Much of the rock art in Morocco has been removed with crow bars and sold in Europe. As of the late 1990s, according to Morocco’s Ministry of Cultural Affairs, 40 percent of the engravings and 10 percent of the paintings had been stolen or damaged. Some works are retouched by local people in order to secure some of the magic they are thought to possess.

Images were protected by archeologist from the weather and sun with varnish-like sealants. The practice was abandoned when some scientists began fearing that moisture captured under the sealant might cause more damage than the sun and weather. The giraffes in Niger described above were discovered fairly recently. Even though they lie in the middle of a remote stretch of desert they are near a road and are considered a tempting targets for looters. In effort to at least secure a copy of these masterpiece scientists working with funding from the National Geographic Society and the Bradshaw Foundation made a plaster caste of the giraffes. [Source: David Coulson, National Geographic, September 1999]

Before the cast was made stone was first carefully cleaned and then sealed with a preservative. Layers of silicon paste were applied. The paste was molded over and picked up every physical detail of the rock art. After it dried, a metal frame was placed over the silicon and a layer of non-binding plaster of Paris was placed on top of that as a protective backing for the image. After the plaster dried, the molds were cut into sections and were placed upside down on the desert to serve as a platform. The silicon mold remained on the image. The rubbery silicon mold was then carefully peeled up and rolled up like a carpet. The whole operation largely came off without a hitch. The molds were then shipped to France, where copies were made.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018