PALEOLITHIC ERA (OLD STONE AGE)

Aurignac Cave

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Archaeologists divide the Stone Age into three very broad periods before humans learned to make and use metal tools: the Paleolithic, or Old Stone Age; the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age; and the Neolithic, or New Stone Age. The oldest division of the Old Stone Age is called the Lower Paleolithic, which spans a huge era of prehistory from about 3 million to 300,000 years ago. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, June 24, 2019]

Archaeologists date the Middle Paleolithic from about 300,000 to 30,000 years ago. During this period, anatomically modern humans are thought to have migrated out of Africa and have begun interacting with and replacing earlier human relatives, such as Neanderthals and Denosovans, in Asia and Europe. Although the stone tools didn't change much, the Middle Paleolithic saw the use of fire became widespread. People at this early time lived in temporary shelters of branches, or in caves and rock shelters where they could find them

The Upper Paleolithic period dates from between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago, depending on the region. This was the time when anatomically modern humans — Homo sapiens — replaced earlier lineages throughout the world, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans — although DNA studies show that they sometimes interbred with them. The Upper Paleolithic period was marked by big changes in stone tools. Instead of the general-purpose stone tools used for hundreds of thousands of years, specialized stone tools began to be developed for specific tasks — such as hafted axes for cutting wood. This period also saw a big increase in figurative artworks, including cave paintings, rock sculptures, and bone, antler and ivory carvings. The natural pigment paintings on the walls of the Altamira cave in northern Spain date from the Upper Paleolithic period, around 30,000 years ago.

After the Upper Paleolithic comes the Middle Stone Age, or Mesolithic period. Scientists disagree if this period really deserves its own name; another term for it is the Epipaleolithic period, which signifies the end of the Old Stone Age. Both terms encompass the end of human hunter-gatherer societies before the revolutions of the Neolithic period. In the Near East and Asia, the Mesolithic spanned from between 20,000 and 8,000 years ago. In Europe, because of the later adoption of Neolithic tools and techniques, the Mesolithic spanned from around 15,000 to 5,000 years ago.

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe” by Andre Debenath , André Debénath , et al. Amazon.com

“The Paleolithic Revolution (The First Humans and Early Civilizations)” by Paula Johanson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Paleolithic Technologies (Routledge Studies in Archaeology)”

by Steven L. Kuhn Amazon.com;

“The Earliest Europeans: A Year in the Life: Survival Strategies in the Lower Palaeolithic (Oxbow Insights in Archaeology) by Robert Hosfield (2020) Amazon.com;

“Earliest Italy: An Overview of the Italian Paleolithic and Mesolithic by Margherita Mussi Amazon.com;

“Cro-Magnon: How the Ice Age Gave Birth to the First Modern Humans” by Brian Fagan (2011) Amazon.com;

“Cro-Magnon: The Story of the Last Ice Age People of Europe” (2023)

by Trenton W. Holliday Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Iberia: Genetics, Anthropology, and Linguistics” by Jorge Martínez-Laso, Eduardo Gómez-Casado (2000) Amazon.com;

“The British Palaeolithic: Human Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World” by Paul Pettitt, Mark White Amazon.com;

“Humans at the End of the Ice Age: The Archaeology of the Pleistocene—Holocene Transition” by Lawrence Guy Straus, Berit Valentin Eriksen (1996) Amazon.com

“Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age” by Erella Hovers, Steven Kuhn (2006) Amazon.com;

Middle Paleolithic Tool Technologies

Prehistoric human existence in Europe is categorized in many cases based on tool technology. The Aurignacian Culture (42,000 to 27,000 years ago) — the first widely recognized modern human culture — is named after the French site that tools associated with it were found. The tools, weapons and adornment found there were used to categorize other Aurignacian sites in Europe. The Aurignacian Period was followed by the Gravettian (26,000 to 22,000 years ago), Solutrean (22,000 to 17,000 years ago) and Magdalenian (17,000 to 12,000 years ago) cultures — all named after French sites. Each site has tools, weapons and adornment associated with it.

Modern humans were not the first to make tools. Neanderthals and Homo erectus also used them. According to the University of California at Santa Barbara: “The most important point to remember about the Middle Paleolithic (about 200,000 years ago to about 40,000 years ago) stone technologies is that the emphasis shifted from core tools, like the Acheulean Handaxe, to flake tools like the Levallois point. Certainly, even at Olduvai, hominids had been taking advantage of sharp-edged flakes and even modifying them for specific tasks. The important difference in the Middle Paleolithic is that cores were being carefully shaped to produce flakes of a predetermined size and shape. The flakes were then further modified into both simple and complex tools. The two main stone tool technologies were: 1) The Levallois Technique (See Mousterian Tools Below) and 2) The Disk Core Technique. [Source: University of California at Santa Barbara =|=]

A Neanderthal Mousterian tool

“The Disk Core Technique is not significantly different from the Levallois Technique (See Below). The technology still depends on careful core shaping and preparation in order to remove ready-to-use flakes for tools. The principal difference in the Disk Core Technique is that even more refinement and skill went into the core preparation so that more flakes could be removed from one core. Thus, the Disk Core technique is really a refinement of trends started by the Levallois technique. The exhausted cores left behind by this process often look like small disks with multiple flake scars, hence the name. =|=

“The most important thing to note about the Disk Core Technique is its efficiency. Using this technique a skilled flinknapper could produce many more usable tools from a single piece of raw material than was possible using any of the other techniques previously discussed. The process you have just seen would then be repeated, first working the other side of the core, then trimming off the rough top and bottom flake scars, perhaps removing tool flakes from the opposite end of the core. Three to five tools could probably be manufactured from a core this size by a skilled craftsman. Eventually, of course, the core would become too small and thin to produce more tools and would be discarded. This final exhausted discoidal form is all the evidence that we have of this remarkable improvement in the efficiency of lithic technology attained by Neanderthals and archaic Homo sapiens.” =|=

Mousterian Tools

The Aurignacian Culture was preceded by the Mousterian culture, whose tools are associated with Neanderthals. The Mousterian industry is a lithic technology that replaced the Acheulean industry in Europe. Believed to have originated more than 300,000 years ago, it is named after the site of Le Moustier in France, where examples were first uncovered in the 1860s, and is associated with both Neanderthal and the earliest modern humans but is believed to have been refined and used primarily by the Neanderthals. Examples of Mousterian tools have been found in Europe and Africa. In Europe, when Mousterian tools are found, it is often assumed that it is a Neanderthal site. [Source: The Guardian, Wikipedia +]

Mousterian tools evolved from Acheulean tools, which are named after the site of Saint-Acheul in France and developed 1.76 million years ago. Acheulean tools were characterized not by a core, but by a biface, the most notable form of which was the hand axe. The earliest Acheulean ax appeared in the West Turkana area of Kenya and around the same time in southern Africa. Acheulean axes are larger, heavier and have sharp cutting edges that are chipped from opposite sides into a teardrop shape.

Mousterian technology it adopted the Levallois technique — a distinctive type of stone knapping — to produce smaller and sharper knife-like tools as well as scrapers. According to the University of California at Santa Barbara: “The Levallois technique of core preparation and flake removal is the earliest of the core preparation technologies. The technology works in four distinct stages. First the edges of a cobble are trimmed into a rough shape. Second, the upper surface of the core is trimmed to remove cortex and to produce a ridge running the length of the core, Third, a platform preparation flake is removed from one end of the core to produce an even, flat striking platform for the blow that will detach the flake. Finally, the end of the core is struck at the prepared platform site, driving a longitudinal flake off of the core following the longitudinal ridge. [Source: University of California at Santa Barbara =|=]

“There are two distinct advantages to this technique. The first is that the flakes removed in this manner are already in a preliminary shape, and only require minor modification before being put to use. Second, more usable cutting edge per pound of raw material can be made this way than can be made by producing core tools. Note how the final shape of this tool closely corresponds to the initial shape of the core from which it was struck. Also, notice how little edge trimming was necessary in order to get a very keen cutting edge on this tool. With care, a number of flakes could be removed from one core, producing much more usable cutting edge with less waste than if the core were thinned into a tool itself.” =|=

Pressure Flaking Invented 75,000 Years Ago in Africa, Not 20,000 Years Ago in Europe

Tools from Blombos cave in South Africa

A highly-skilled tool-making technique that shapes stones into sharp-edged tools was thought to have originated in Europe 20,000 years ago but in fact appears to have been invented by Africans some 75,000 years ago. The technique known as pressure-flaking involves using an animal bone or some other object to exert pressure near the edge of a stone piece and precisely carve out a small flake. Stone tools shaped by hard stone hammer strikes and then struck with softer strikes from wood or bone hammers. Edges are carefully trimmed by directly pressing the point of a tool made of bone on the stone. [Source: Discovery.com, Reuters, October 28, 2010 |~|]

Discovery.com reported: “Researchers from the University of Colorado at Boulder examined stone tools dating from the Middle Stone Age, some 75,000 years ago, from Blombos Cave in what is now South Africa. The team found that the tools had been made by pressure flaking, whereby a toolmaker would typically first strike a stone with hammer-like tools to give the piece its initial shape, and then refine the blade’s edges and shape its tip. |~|

“The technique provides a better means of controlling the sharpness, thickness and overall shape of two-sided tools like spearheads and stone knives, said Paola Villa, a curator at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History and a co-author of the study published in the journal Science. “Using the pressure flaking technique required strong hands and allowed toolmakers to exert a high degree of control on the final shape and thinness that cannot be achieved by percussion,” Villa said. “This control helped to produce narrower and sharper tool tips...These points are very thin, sharp and narrow and possibly penetrated the bodies of animals better than that of other tools.” |~|

“To arrive at their conclusion that prehistoric Africans could have been the first to use pressure flaking to make tools, the researchers compared stone points, believed to be spearheads, made of silcrete — quartz grains cemented by silica — from Blombos Cave, and compared them to points that they made themselves by heating and pressure-flaking silcrete collected at the same site. |~|

“The similarities between the ancient points and modern replicas led the scientists to conclude that many of the artifacts from Blombos Cave were made by pressure flaking, which scientists previously thought dated from the Upper Paleolithic Solutrean culture in France and Spain, roughly 20,000 years ago. “Using the pressure flaking technique required strong hands and allowed toolmakers to exert a high degree of control on the final shape and thinness that cannot be achieved by percussion,” Villa said. “This finding is important because it shows that modern humans in South Africa had a sophisticated repertoire of tool-making techniques at a very early time.” The authors speculated that pressure flaking may have been invented in Africa and only later adopted in Europe, Australia and North America.” |~|

The co-authors included Vincent Mourre of the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research and Christopher Henshilwood of the University of Bergen in Norway and director of the Blombos Cave excavation. “This flexible approach to technology may have conferred an advantage to the groups of Homo sapiens who migrated out of Africa about 60,000 years ago,” the authors wrote in Science. |~|

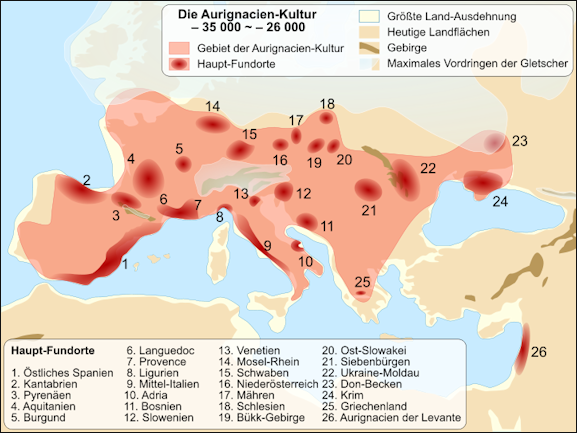

Aurignacian Culture

Prehistoric human existence in Europe is categorized in many cases based on tool technology. The Aurignacian Culture (42,000 to 27,000 years ago) — the first widely recognized modern human culture — - is named after the French site that tools associated with it were found. The tools, weapons and adornment found there were used to categorize other Aurignacian sites in Europe. The Aurignacian Period was followed by the Gravettian (26,000 to 22,000 years ago), Solutrean (22,000 to 17,000 years ago) and Magdalenian (17,000 to 12,000 years ago) cultures — all named after French sites. Each site has tools, weapons and adornment associated with it.

Aurignacian tools are named after the French site of Auriganc where the tools were first found. They consisted of blades and advanced bone tools. Because the oldest Aurignacian tools predate the earliest modern human fossils in Europe, some scientists think they have been made by Neanderthals. The people of this culture also produced some of the earliest known cave art,

Aurignacian culture map

The long blades (rather than flakes) of the Upper Palaeolithic Mode 4 industries appeared during the Upper Palaeolithic between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago. The Aurignacian culture is a good example of mode 4 tool production. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Aurignacian industry is characterized by worked bone or antler points with grooves cut in the bottom and included tools, double end scrapers, burins, pins and awls. Their flint tools include fine blades and bladelets struck from prepared cores rather than using crude flakes. The most durable and physical evidence the Aurignacian culture left behind are stone tools. They refined their core and blade lithic technology to a high level.

Stone tools from the Aurignacian culture are known as Mode 4, characterized by blades (rather than flakes, typical of mode 2 Acheulean and mode 3 Mousterian) from prepared cores. Also seen throughout the Upper Paleolithic is a greater degree of tool standardization and the use of bone and antler for tools. Based on the research of scraper reduction and paleoenvironment, the early Aurignacian group moved seasonally over greater distance to procure reindeer herds within cold and open environment than those of the earlier tool cultures. The burin — a tool with a narrow sharp face at the tip used for engraving and other purposes — is often found at Aurignacian sites

Aurignacian tools appeared when it is believed modern humans developed language and boats. This was a period when humans reached points all over the globe. It is believed that early modern humans were trading quality stone as early as 100,000 years ago. Shells have been found hundreds of miles from where they originated. Unlike most of their ancestors who made stone tools from localized sources, modern humans quarried fine-grained and colorful flints from as far away as 250 miles away from they lived and most likely formed trade networks to efficiently distribute these flints to a large number of people. Based on the presence of tools found at one site that were made from materials found at a distant site it appears that other hominids, including relatively primitive Australopithecus , also engaged in trade or migrated to sites to obtain quality stone.[Source: John Pfieffer, Smithsonian magazine, October 1986]

Aurignacians: Producers of Europe's First Great Art?

Chauvet cave image made during the Aurignacian period

Many of the sites where Aurignacian tools are found also contain art: sculptures or cave paintings. The people of this culture also produced some of the earliest known cave art, such as the animal engravings at Trois Freres and the paintings at Chauvet cave in southern France. They also made pendants, bracelets, and ivory beads, as well as three-dimensional figurines. Perforated rods, thought to be spear throwers or shaft wrenches, also are found at their sites. [Source: John Pfieffer, Smithsonian magazine, October 1986]

The Aurignacian people is the name given to the early modern humans that created Europe's first art works. On their skill the German film director Werner Herzog said: “We should never forget the dexterity of these people. They were capable of creating a flute. It is a high-tech procedure to carve a piece of mammoth ivory and split it in half without breaking it, hollow it out, and realign the halves.

“We have one indicator of how well their clothing was made. In a cave in the Pyrenees, there is a handprint of a child maybe four or five years old. The hand was apparently held by his mother or father, and ocher was spit against it to get the contours and you see part of the wrist and the contours of a sleeve. The sleeve is as precise as the cuffs of your shirt. The precision of the sleeve is stunning.

“Aurignacian people that lived in Europe between 37,000 and 28,000 years ago have been divided into three subcultures based on the ornaments they wore: usually teeth, bones or and shells with a hole or a groove to accommodate a chords. A group that lived in present-day Germany and Belgium preferred perforated teeth and disk-shaped ivory beads. In Austria, southeast France, Greece and Italy they preferred shell. A third group lived in Spain and southern and western France.”

Gravettian Culture

Gravettian tools

The Gravettian populations were widespread around Europe about 32,000-24,000 years ago. The Gravettian people were hunter-gatherers who were also adept artisans. The culture is named after the La Gravette site in southwestern France where tools associated with it were found. Gravettian tools include hand-held spears, which made the hunting of large animals more feasible. There are also weapons and adornment associated with the Gravettian culture. The end of the Gravettian culture roughly coincides with Last Glacial Maximum — 25,000 to 19,000 years ago — the coldest part of the last Ice Age.[Source: Wikipedia +]

The Gravettian culture is archaeologically the last European culture many consider unified. It had mostly disappeared by 22,000 years ago, close to the Last Glacial Maximum, although some elements lasted until c. 17,000 years ago. At this point, it was replaced abruptly by the Solutrean in France and Spain, and developed into or continued as the Epigravettian in Italy, the Balkans, Ukraine and Russia. The Gravettian culture is famous for Venus figurines, which were typically made as either ivory or limestone carvings. +

Clubs, stones and sticks were the primary hunting tools during the Upper Paleolithic period. Bone, antler and ivory points have all been found at sites in France; but proper stone arrowheads and throwing spears did not appear until the Solutrean period (~20,000 Before Present). Due to the primitive tools, many animals were hunted at close range. The typical artefact of Gravettian industry, once considered diagnostic, is the small pointed blade with a straight blunt back. They are today known as the Gravette point, and were used to hunt big game. Gravettians used nets to hunt small game, and are credited with inventing the bow and arrow. Gravettian burin was a tool with a narrow sharp face at the tip used for engraving and other purposes.

The Gravettians were hunter-gatherers who lived in a bitterly cold period of European prehistory, and Gravettian lifestyle was shaped by the climate. Pleniglacial environmental changes forced them to adapt. West and Central Europe were extremely cold during this period. Archaeologists usually describe two regional variants: the western Gravettian, known mainly from cave sites in France, Spain and Britain, and the eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians, which include the Pavlovian culture, were specialized mammoth hunters,[8] whose remains are usually found not in caves but in open air sites. Moravianska Venus

Gravettian culture thrived on their ability to hunt animals. They utilized a variety of tools and hunting strategies. Compared to theorized hunting techniques of Neanderthals and earlier human groups, Gravettian hunting culture appears much more mobile and complex. They lived in caves or semi-subterranean or rounded dwellings which were typically arranged in small "villages". Gravettians are thought to have been innovative in the development of tools such as blunted black knives, tanged arrowheads and boomerangs. Other innovations include the use of woven nets and stone-lamps. Blades and bladelets were used to make decorations and bone tools from animal remains. Sites including CPM II, CPM III, Casal de Felipe, and Fonte Santa (all in Spain) have evidence the use of blade and bladelet technology during the period. The objects were often made of quartz and rock crystals, and varied in terms of platforms, abrasions, endscrapers and burins. They were formed by hammering bones and rocks together until they formed sharp shards, in a process known as lithic reduction. The blades were used to skin animals or sharpen sticks.

Gravettian culture extended across a large geographic region, but is relatively homogeneous until about 27,000 years ago. They developed burial rites, which included the inclusion of simple, purpose built, offerings and or personal ornaments owned by the deceased, placed within the grave or tomb. Surviving Gravettian art includes numerous cave paintings and small, portable Venus figurines figurines made from clay or ivory, as well as jewelry objects. The fertility deities mostly date from the early period, and consist of over 100 known surviving examples. They conform to a very specific physical type of large breasts, broad hips and prominent posteriors. The statuettes tend to lack facial details, with limbs that are often broken off.

Erik Trinkaus, a professor of physical anthropology at Washington University, told Discovery News that the people from Gravettian culture, were “very effective at exploiting lots of resources, making the oldest textiles, having elaborate burials and clothing, and producing a variety of forms of art.” There is evidence of trade of amber and exotic stones in Europe in 28,000 B.C. Based on the large variety of artifacts found, A large cave called Mas-d'-Azil in southern France was regarded as a gathering place for people to exchange gods and gifts and possible find mates.

Fournol, Věstonice and Epigravettians

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: A previously unknown Gravettian lineage — dubbed Fournol, after a French site that is the earliest known location associated with this genetic cluster — inhabited what is now France and Spain. Another — named Věstonice after a Czech site — stretched across today's Czech Republic and Italy. The Fournol descended from the Aurignacians, the earliest known hunter-gatherer culture in Europe, which lasted from about 43,000 to 33,000 years ago. In contrast, the Věstonice descended from the Kostenki and Sunghir groups farther east from what is now western Russia, who were contemporaries of the Aurignacians. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, March 2, 2023]

There are some cultural differences between these two lineages. For instance, Fournol people buried their dead in caves, and sometimes may have ritually cut the bones after death, Posth said. In contrast, the Věstonice buried their dead with funeral goods, personal ornaments and the red mineral ochre in open air or cave sites. People of the Fournol and Věstonice lineages may have possessed darker skin and eye color than some of the lineages that came after them, the new genome study suggests. However, Posth warned that "it is not possible to know their exact skin and eye colors, because those traits might be influenced by multiple other genes."

The Fournol genetic signature survived the Last Glacial Maximum, lasting for at least 20,000 years. Their descendants sought refuge in what is now Spain and southern France during the Last Glacial Maximum and later spread northeast to the rest of Europe. In contrast, the Věstonice died out. Previously, scientists thought the Italian peninsula was a refuge for Gravettians during the Last Glacial Maximum, with the people there eventually forming the so-called Epigravettian culture after the glaciers retreated. However, the new findings show the Věstonice were not genetically detectable after the Last Glacial Maximum.

Instead, the new study finds the Epigravettians actually descended from Balkan groups that entered Italy as early as 17,000 years ago. "Right after the Last Glacial Maximum, the genetic makeup of the human groups living in the Italian peninsula changed dramatically," Ludovic Orlando, a molecular archaeologist at Paul Sabatier University in Toulouse, France, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

Starting about 14,000 years ago, the Epigravettians spread from the south across the rest of Europe, supplanting the Magdalenians, who were descended in part from the Fournol. The Magdalenians hunted reindeer that lived on the steppe, while the Epigravettians specialized in hunting forest prey. An abrupt warming event helped forests spread across Europe into what once was steppe, and the Epigravettians moved northward as well, Posth said.

Nine Different Gravettian Cultures Based on Jewelry Types Identified

During the Gravettian Period, prehistoric humans in Europe adorned themselves with such a wide variety of beads that researchers have classified nine distinct cultural groups across the continent based on their location and distinctive styles according to a study published in January 2024 in the journal Nature Human Behaviour. Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science:The Gravettians' crafting skills can be seen in the variety of materials they used to make beads, such as ivory, bones, teeth (including those from bears, horses and rabbits), antlers, jet gemstones, shells and amber. These beads likely served as personal ornaments as well as cultural markers. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, January 30, 2024]

For the study, the researchers analyzed 134 "discrete types" of adornments collected by archaeologists over the past century or so from 112 sites around Europe, according to a statement. The team then inputted the information they collated from previous scientific studies and other literature into a database, which enabled them to begin identifying the distinctions between the different groups' beads. "We started noticing differences as we were making the database," study lead author Jack Baker, a doctoral student of prehistory at the University of Bordeaux in France, told Live Science. "There's actually a big difference, especially between the west and the east."

For example, researchers noticed that foxes and red deer, both of which were abundant across the continent during the period, were only incorporated into beads created by certain groups. "At this time, foxes and red deer were everywhere," Baker said. "However, we only see people wearing fox canines in the east, even though you can get them everywhere. And we only really find people wearing red deer canines in the west. So even though they're available everywhere, there's a clear difference in what they're choosing."

Homo Sapiens in Europe

solutrean distribution There was also movement of materials between different groups, which can be seen for example at a burial site in Italy, where the remains of an adolescent boy were adorned with materials that originated hundreds of miles away. "So, we know that things were being moved around," Baker said. "We know especially that teeth have been moved around and fossil shells [too]. Movement of materials was 100 percent happening."

Researchers determined that while geographical separation may partially explain these differences in bead selection between the nine groups, "culturally driven boundaries" was a much larger factor, according to the statement. For instance, burials were a "common cultural trait in Early and Middle Gravettian people in Eastern Europe," but later on there was a shift away from burying the deceased, according to the study.

Researchers were able to confirm most of the cultural groups' existence based on existing genetic data in the archaeological record, but they couldn't identify one eastern European group as there was no known genetic data available. An additional two cultural groups in Iberia only had genetic data from the same single individual, according to the statement. "Genetics is a really powerful tool, but genetics doesn’t really equal culture," Baker said. "So even though we know about these genetic groups, that doesn't necessarily reflect their culture, which I think is really an important message."

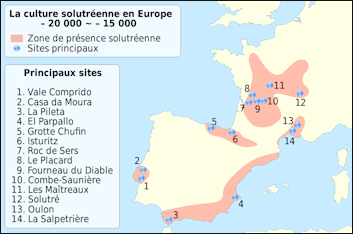

Solutrean Culture

The Solutrean Period (22,000 to 17,000 years ago) is named after the French site — the Crôt du Charnier site in Solutré-Pouilly, in Saône-et-Loire. — that tools associated with it were found. The site has tools, weapons and adornment associated with it. The people of Solutré specialised in the hunting of horses and they appeared to have occupied the site periodically, presumably in the hunting season. It does not include living areas occupied for long periods, but there are specialised areas of activity, especially the processing of game after the hunt.[Source: Donsmaps.com ==]

Brian Vastag wrote in the Washington Post: “ Little is known about the Solutrean people. They lived in Spain, Portugal and southern France beginning about 25,000 years ago. No skeletons have been found, so no DNA is available to study. But the Solutreans did leave behind rock art, which showed a diamond-shaped flat fish in delicate black etchings. It looks like a halibut. A seal also appears, an arrow-headed line stabbing through it. [Source:Brian Vastag, Washington Post, February 29, 2012]

According to Donsmaps.com: “Some tools - pointes à face plane, laurel leaves, shouldered points - were made by a sophisticated retouch that was obtained by a new technique called pressure flaking, on flint which had been heat treated to make it much more workable. To make these lanceolate (leaf-shaped) points, the Solutrean people developed an exceptionally deft technique of pressure flaking – pressing with a soft tool such as an antler tine or bone point – instead of striking directly with a soft or hard hammer. There are other examples of this technique in prehistoric implements but the Solutrean people raised this technique to an artform where their arrowheads and spearpoints were as efficient as possible and like many optimum designs - an aircraft's wing, say – they also exhibit a form of beauty. ==

“The Solutrean technology is largely isolated in the prehistoric record. It was preceded by an industry based on Acheulian bifaces and scraper tools and it was succeeded by the widespread adoption of microlith technology in the Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods. It was the dominant technology for the relatively short space of time from 21 000 years ago to circa 15 000 years ago.”

Mladec Caves and Dolní Věstonice

Venus from Dolni Vestonice

The Mladeč Caves is the Czech Republic is regarded by some as the world’s oldest “village.” Bones found there, dated to 31,000 years before present, are claimed to be the oldest human bones that clearly represent a human settlement in Europe. Located 10 kilometres from Hanácké Benátky, which is not far from the Morava river, the town of Litovel and the protected nature landscape area of Litovelské Pomoraví, the caves comprise a complex, multi-floor labyrinth of fissure passages, caves and domes inside the calcit hill Třesín. Some of the underground spaces are richly decorated. [Source: CzechTourism, Wikipedia]

Dolní Věstonice is another candidate for the world’s oldest “village” based on its age and the large amount artisanship and activity that went on there. An Upper Paleolithic archaeological site near the village of Dolní Věstonice, Moravia in the Czech Republic,on the base of 549-meter-high Děvín Mountain, it thrived 26,000 years ago based on radiocarbon dating of objects and remains found there. The site is unique and special because of the large number of prehistoric artifacts (especially art), dating from the Gravettian period (roughly 27,000 to 20,000 B.C.) Found there. The artifacts include includes carved representations of men, women, and animals, along with personal ornaments, human burials and enigmatic engravings. [Source: Wikipedia]

The stone-age men at Dolni Vestonice and Pavlov sites in the Czech Republic had textiles, ceramics, cords, mats, and baskets. Evidence of these things are impressions left on clay chips recovered from clay floors hardened by a fire. The impressions of textiles indicate that these people may have made wall hangings, cloth, bags, blankets, mats, rugs and other similar items.

Some of earliest known ceramics were found at Dolni Vestonice and Pavlove, hill sites in the Czech Republic that were the home of prehistoric seasonal camps. Thousands of fragments of human figures, as well as the kilns that produced them have been found in sites in Moravia in what is now Russia the Czech Republic. Some have been dated to be 26,000 years old. The figurines were made from moistened loess, a fine sediment, and fired at high temperatures. Predating the first known ceramic vessels by 10,000 years, the figurines, some scientists believe, were produced and exploded on purpose based on the fact that most of the sculptures have been found in pieces.

See Mladeč Caves and Dolní Věstonice Under EARLY MODERN HUMAN HOMES, SETTLEMENTS AND POSSESSIONS europe.factsanddetails.com

Mesolithic Period (Middle Stone Age)

Mesolithic Period (Middle Stone Age) is an archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic primarily used to describe Europe and the Middle East. It refers to the final period of hunter-gatherer cultures in these regions between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the Neolithic Revolution. It extends roughly from 15,000 to 5,000 years ago in Europe; and from 20,000 to 10,000 years ago in the Middle East. The term is less used of areas farther east, and not at all beyond Eurasia and North Africa. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymously, especially for outside northern Europe, and for the corresponding period in the Levant and Caucasus. The Mesolithic has different time spans in different parts of Eurasia.

According to Live Science: The Mesolithic period for humans was a time of severe climate change across the world. At this time, the ice sheets that covered much of northern Europe, Asia and North America began to melt away, creating new lands that became populated by animal herds and people. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, June 24, 2019]

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “About 14,500 years ago, as Europe began to warm, humans followed the retreating glaciers north. In the ensuing millennia, they developed more sophisticated stone tools and settled in small villages.[Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, August 2019]

See Separate Article: MESOLITHIC PERIOD (MIDDLE STONE AGE) IN EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

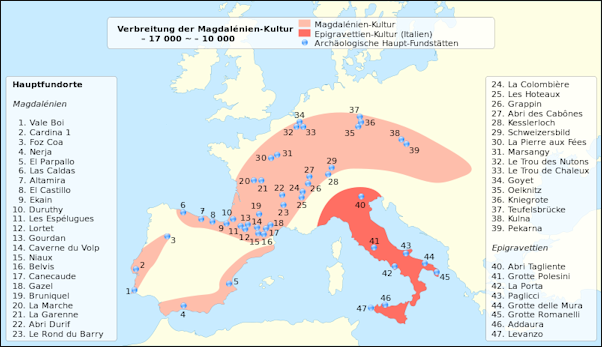

Magdalenian Culture

Around 19,000-14,000 years ago, the Magdalenian culture was spread over vast parts of Europe. It is named after the French site — La Madeleine, a rock shelter in the Vézère valley, in the Dordogne region of France — that tools associated with it were found. The site has tools, weapons and adornment associated with it. The culture originated during the Last Glacial Maximum — roughly 25,000 to 19,000 years ago — the coldest part of the last Ice Age.

According to Les Eyzies Tourist Information: “The Magdalenien is characterised by regular blade industries struck from carinated cores. Typologically the Magdalenian is divided into six phases which are generally agreed to have chronological significance. The earliest phases are recognised by the varying proportion of blades and specific varieties of scrapers, the middle phases marked by the emergence of a microlithic component (particularly the distinctive denticulated microliths) and the later phases by the presence of uniserial (phase 5) and biserial ‘harpoons’ (phase 6) made of bone, antler and ivory. [Source: leseyzies-tourist.info +/]

Homo Sapiens in Europe Magdalenian distribution

“By the end of the Magdalenian, the lithic technology shows a pronounced trend towards increased microlithisation. The bone harpoons and points are the most distinctive chronological markers within the typological sequence. As well as flint tools, the Magdalenians are best known for their elaborate worked bone, antler and ivory which served both functional and aesthetic purposes including bâtons de commandement. Examples of Magdalenian mobile art include figurines and intrically engraved projectile points, as well as items of personal adornment including sea shells, perforated carnivore teeth (presumably necklaces) and fossils. +/

“The sea shells and fossils found in Magdalenian sites can be sourced to relatively precise areas of origin, and so have been used to support hypothesis of Magdalenian hunter-gatherer seasonal ranges, and perhaps trade routes. Cave sites such as the world famous Lascaux contain the best known examples of Magdalenian cave art. The site of Altamira in Spain, with its extensive and varied forms of Magdalenian mobillary art has been suggested to be an agglomeration site where multiple small groups of Magdalenian hunter-gatherers congregated.” +/

See Separate Article: MESOLITHIC PERIOD (MIDDLE STONE AGE) IN EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024