OUT OF AFRICA THEORY

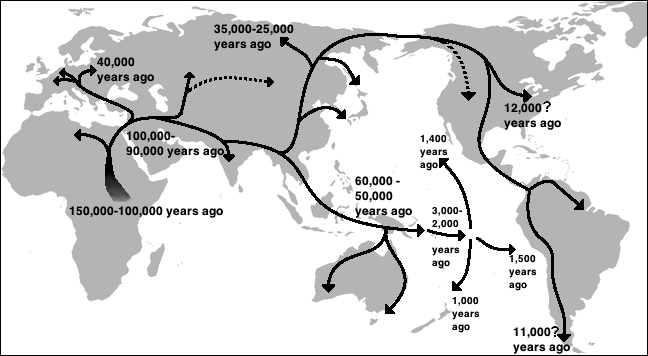

There are various theories describing how migration patterns played a part in the development of early humans. The traditional, widely-accepted "Single Origin, Out of Africa Theory" of human evolution posits that: 1) earliest hominids evolved in Africa; 2) Australopithecus species evolved into Homo species in Africa; 3) early Homo species migrated to Asia and the Old World from Africa between a million and two million years ago; and 4) Homo sapiens also evolved in Africa and migrated outward from there.

The traditional "Out of Africa" theory holds that there were two migrations of African-originating species. First, Homo erectus began slowly moving into the Middle east, Europe and Asia around 1.8 million years ago. And second, Homo sapiens began migrating into the same areas starting around 100,000 year ago. Scientists that uphold this theory argue that all modern humans have evolved from African Homo sapiens.

Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London wrote: “Unraveling the first migrations of anatomically modern humans out of Africa has invoked great interest among researchers from a wide range of disciplines. Available fossil, archeological, and climatic data offer many hypotheses, and as such genetics, with the advent of genome-wide genotyping and sequencing techniques and an increase in the availability of ancient samples, offers another important tool for testing theories relating to our own history. In this review, we report the ongoing debates regarding how and when our ancestors left Africa, how many waves of dispersal there were and what geographical routes were taken.” [Source: Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London, “Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate,” Evolutionary Bioinformatics, April 21, 2016]

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

See Separate Articles: MIGRATIONS OF EARLY MODERN HUMANS factsanddetails.com ; SOUTHERN ROUTE OF OUT OF AFRICA THEORY africame.factsanddetails.com ; NORTHERN ROUTE OF OUT OF AFRICA THEORY africame.factsanddetails.com ; EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO ASIA factsanddetails.com ; EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO AUSTRALIA factsanddetails.com ; FIRST MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO EUROPE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia” by John G Fleagle, John J. Shea, Editors (2010), Amazon.com;

“The Global Prehistory of Human Migration” by Immanuel Ness and Peter Bellwood (2014) Amazon.com;

“Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World” by Stephen Oppenheimer Amazon.com;

“The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey” (Princeton Science Library) by Spencer Wells (2017) Amazon.com;

“Past Human Migrations In East Asia by Alicia Sanchez-Mazas” Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“The Forgotten Exodus: The Into Africa Theory of Human Evolution” by Bruce Fenton (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Real Eve: Modern Man's Journey Out of Africa” by Stephen Oppenheimer (2004) Amazon.com;

“Asian Paleoanthropology: From Africa to China and Beyond” (Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology) by Christopher J. Norton and David R. Braun Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

Out of Africa, Multiregional and Assimilation Models

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: “The most bitterly debated question in the discipline of human evolution is likely over where modern humans evolved. The out-of-Africa hypothesis maintains that modern humans evolved relatively recently in Africa and then spread around the world, replacing existing populations of archaic humans. The multiregional hypothesis contends that modern humans evolved over a broad area from archaic humans, with populations in different regions mating with their neighbors to share traits, resulting in the evolution of modern humans. The out-of-Africa hypothesis currently holds the lead, but proponents of the multiregional hypothesis remain strong in their views.”[Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, February 22, 2011]

Chris Stringer wrote in The Guardian: The idea of multiregional evolution” is ”an updated version of ideas from the 1930s. It envisaged deep parallel lines of evolution in each inhabited region of Africa, Europe, Asia and Australasia, stretching from local variants of H. erectus right through to living people in the same areas today. These lines did not diverge through time, since they were glued together by interbreeding across the ancient world, so modern features could gradually evolve, spread and accumulate, alongside long-term regional differences in things like the shape of the face and the size of the nose. [Source: Chris Stringer, The Guardian, June 19, 2011]

“The assimilation model “took the new fossil and genetic data on board and gave Africa a key role in the evolution of modern features. However, this model envisaged a much more gradual spread of those features from Africa than did mine. Neanderthals and archaic people like them were assimilated through widespread interbreeding. Thus the evolutionary establishment of modern features was a blending process rather than a rapid replacement.”

Out of Africa Theory and Modern Humans (Homo Sapiens)

Modern human skull

Modern humans first arose at least 300,000 years ago in Africa, with oldest modern human fossils, from Morocco, dated to 300,000 years ago. Where the first modern humans originated and how they crossed the Sahara and dispersed from Africa has long been controversial. Earlier research suggested the migration from Africa started between 70,000 and 40,000 years ago. A study published in the mid 2010s suggested that modern humans might have begun their migration to Asia and Europe as early as 130,000 years ago, and expanded out of Africa in multiple waves. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, May 28, 2015]

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: “Modern humans expanded out of Africa, spreading rapidly across most of the world's lands to colonize all continents except Antarctica, reaching even the most remote Pacific islands. A number of scientists conjecture this migration was linked with a mutation that transformed our brains, leading to our modern, complex use of language and enabling more sophisticated tools, art and societies. The more popular view suggests hints of such modern behavior existed long before this exodus, and that humanity instead had crossed a threshold in terms of population size in Africa that made such a revolution possible.” [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, February 22, 2011]

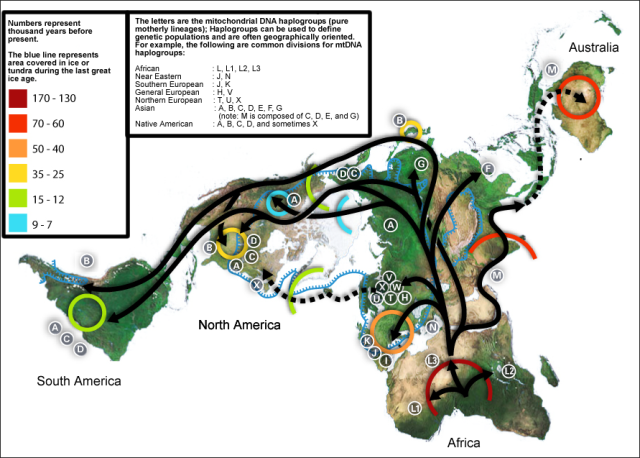

Some scientists believe that modern humans developed from archaic homo sapiens that migrated out of Africa about 100,000 years ago, replacing older homo species (archaic homo sapiens ) . Others argue that modern humans evolved out from Homo erectus populations in different parts of the world with some genetic exchange between groups. DNA studies show that the group that became Africans and the group that became non-Africans split apart 189,000 years ago, much earlier than it was thought that non-Africans left Africa. According to DNA evidence the first group of hominids that left Africa had less than 50 members.

The warmest period of the last major interglacial period was around 125,000 years ago, when sea levels were 20 to 30 feet higher than they are today. Areas of Africa, the Middle East and West Asia that are desert today were covered by tropical deciduous forests and savannas dotted with numerous lakes. These habitats may have provided corridors for early Homo sapiens to migrate out of Africa.

The oldest confirmed fossils of modern humans are 300,000 years old from North Africa and 80,000 years old from Asia and 50,000 years old from Europe. Tool evidence pushes the dates further back in time. DNA studies back the Out of Africa Theory. The most conclusive are based on samples of mitochondrial DNA taken from more than a thousand men all over the world. Mitochondrial DNA is passed down from generation to generation by men in the Y chromosome. It shows that the further ethnic groups are from Africa the more different they are. Based on mitochondrial DNA data people today from Sudan, Ethiopia and Southern Africa are the closest lineal descendants of the first homo sapiens. Additionally, the fact that people of African descent have a greater of variation of certain genes suggest that they had more time to develop these variation, which means people must have evolved in Africa first.

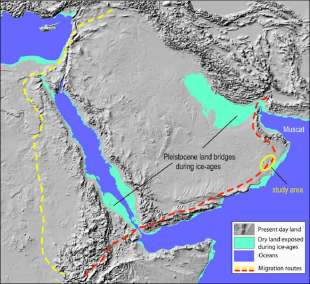

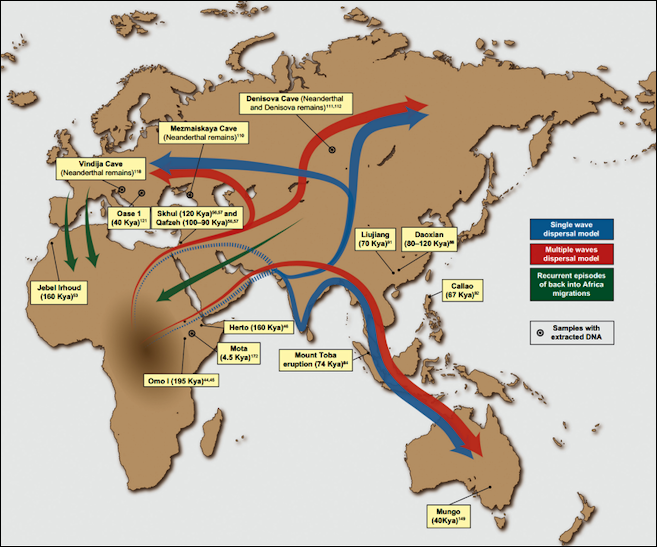

Single Dispersal from Africa

Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London wrote: One “topic of ongoing controversy relates to whether the first modern humans to leave Africa were part of a unique dispersal event or whether in fact there were multiple waves of dispersal out of Africa to populate the rest of the world. A single dispersal model states that anatomically modern humans migrated out of Africa to the rest of Eurasia as a single wave exiting via a single route, whether North or South. As discussed previously, variants of the single dispersal model differ in their timing, for example, after 50,000 years ago with complete population replacement under the upper Paleolithic model, versus those postulating as early as 100,000–125,000 years ago based on the Skhul and Qafzeh remains and climatic data. They also differ on the exact route taken, for example, single coastal dispersal models 50,000–75,000 years ago versus models governed by the location of discovered archeological artifacts, such as the Jebel Faya and Nubian models, based on artifacts found in present-day United Arab Emirates and North-East Africa, respectively. [Source: Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London, “Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate,” Evolutionary Bioinformatics, April 21, 2016 ~]

“Under all of these models, genetic evidence suggests that migration out of Africa was accompanied by a severe bottleneck in the initial migrating group(s), drastically reducing the genetic diversity before a rapid expansion. The serial founder effect model is one possible description of a single dispersal model, by which the dispersal out of Africa occurred initially via a single migrant group and continued in an iterative way as individuals dispersed into unoccupied regions, expanded in population size, and gave rise to new groups of founder individuals who again expanded into unoccupied areas. This serial founder process could give rise to the patterns of increasing genetic drift and decreasing genetic diversity observed in groups as geographic distance from Africa increases. ~

“However, recent work by Pickrell and Reich has shown that the inverse correlation observed between heterozygosity and geographic distance can be generated under further historical models that all deviate in some way from the serial founder effect model and yet not as extreme as the multiple dispersals model. Primarily, they present models of dispersal characterized by fewer bottlenecks and more pervasive admixture that can also account for the patterns of heterozygosity we see in global populations. ~

“East Asia is a key region when considering the nature of the first modern human dispersals. Under a single dispersal model, the peopling of East Asia is hypothesized to have occurred via a single wave, with, for example, Aboriginal Australians surmised to have diversified from within this East Asian wave of individuals. Recent whole-genome studies reveal a split between Europeans and Asians dating to 17,000–43,000 years ago, which seems in conflict with archeological evidence from greater Australia (Australia and Melanesia, including New Guinea), suggesting the presence of Anatomically modern human occupation in this region around 50,000 years ago. This evidence casts doubt on the single wave dispersal framework, as it has been suggested that this would allow insufficient time for Anatomically modern humans to have migrated to greater Australia. Addressing this idea, Wollstein et al investigated several dispersal hypotheses relating to the colonization and demographic history of Oceania. Using dense SNP array data and by simulating different demographic models for the occupation of this region, they found that the most parsimonious scenario involved a split of New Guineans from a common Eurasian ancestor population, rather than a separate early migration event. ~

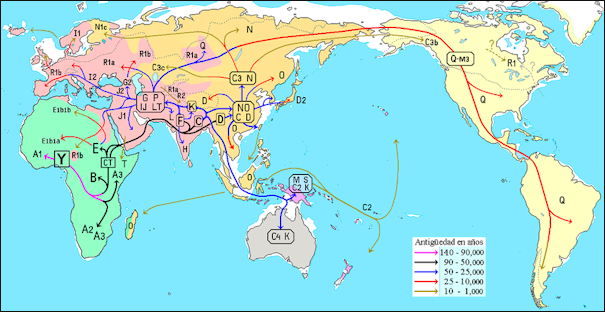

Migration of haplogroups ADN-Y

Multiple Dispersals from Africa

Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London wrote: “Lahr and Foley were the first to propose that anatomically modern humans populated the world via multiple rather than a single wave of expansion from a morphologically variable population in Africa. Under their multiple dispersals model, there was an initial dispersal between 50 and 100,000 years ago through South Arabia to Southeast Asia (the Southern route) and a second migration following the Northern route, through the Levant, that led to the colonization of the rest of Eurasia between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago. They suggested that each of these dispersals was different in terms of the associated artifacts, with the first migration into the Arabian Peninsula affiliated with Middle Paleolithic stone tools and the later expansion through the Levantine corridor into Europe consistent with the appearance of upper Paleolithic tools. Later work by Field and Lahr used a geographical information system-based model, incorporating climatic data from 74,000 to 59,000 years ago, to show that both a Northern and a Southern route out of Africa would have been possible given environmental barriers. [Source: Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London, “Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate,” Evolutionary Bioinformatics, April 21, 2016 ~]

“More recently, McEvoy et al tested the multiple dispersals hypothesis by applying a LD-based approach to ∼200,000 SNPs in 17 global populations. They estimated the split time between these populations using mathematical models that relate the split time to FST between populations and the effective population size (Ne) of populations, assuming a simple bifurcating tree model. By testing divergence times in West and East Eurasian populations simultaneously, they found evidence for a more complex Out of Africa scenario than that suggested by a single dispersal model. Namely, they demonstrated a significant difference in estimates of African/European and African/East Asian divergence times (40,000 and 36, 000 years ago, respectively). These dates are more recent than those previously proposed but nonetheless may indicate that Europe and East Asia were occupied by separate Anatomically modern human dispersals. The same technique was used in recent work to explore divergence times between Europe and Africa and Australo-Melanesia and Africa. The split time for European and East African populations (57,000–76,000 years ago) was again estimated to be somewhat more recent than that for East Asia and Africa (73,000–88,000 years ago), and significantly more recent than that between Australo-Melanesians and Africa (87,000–119,000 years ago) even after accounting for Denisovan introgression into the ancestors of Australo-Melanesians. According to the authors, this is again inconsistent with a single wave dispersal and suggests that Australo-Melanesian populations retain signals of an ancient divergence from Africa. This fits well with the discovery of artifacts associated with human colonization at the Huon Peninsula of Papuan New Guinea and the Mungo Man remains, the oldest Anatomically modern human found in Australia, dated at 40,000 years ago. ~

single versus multiple waves of human migration(s)

“Templeton stressed the importance of genetic interchange under a multiple dispersals scenario.149 His model suggests that ancestors of modern humans, some of which did not necessarily have Anatomically modern human features, expanded out of Africa many times during the Pleistocene and that these expansions were never sufficient to remove the genetic contributions of previous dispersals, resulting in interbreeding between dispersing groups rather than population replacement. Further support for this model was recently provided by Reyes-Centeno et al who used morphological data from Holocene human cranial samples found in Asia, in conjunction with genetic data, to evaluate models of modern human dispersals out of Africa.They concluded that a single dispersal model was likely too simplistic and, as with other studies, found that modern humans first went south upon leaving African and only later took the Northern route in a second expansion wave. Recently published work providing evidence for modern human introgression into the ancestors of East Asian Neanderthals 100,000 years ago also gives support for the multiple dispersals hypothesis. ~

“In the same vein, it has been suggested that some isolated Southeast Asian/Oceania populations, such as Papuans and Andamanese and Malaysian Negritos, represent relic populations of a first wave Out of Africa. Some of this evidence is in light of autosomal DNA studies that have indicated Southeast Asia was settled by multiple waves of peoples, the first most related ancestrally to modern day groups such as the Onge and the second more closely related ancestrally to modern day East Asians. However, it remains challenging to disentangle whether differences in inferred ancestry are the result of long-term physical isolation and low population sizes rather than a separate wave of Out of Africa migration. ~

“Genetic evidence for an early Southern exit was presented by Rasmussen et al who analyzed a lock of hair from a 100-year-old Australian Aborigine. Applying D statistics to segregating sites in the genomes of modern Africans, Europeans, and Asians, they provided evidence for an early branching of Australian Aborigines 75,000–62,000 years ago. These results suggest that the ancestors of Australian Aborigines are some of the best modern day representatives of a possible early human dispersal into East Asia, although such a conclusion is still a matter of controversy. ~

“Opponents of an early migration into Australia and Oceania assert that if an early migration had taken place before Anatomically modern humans spread into Eurasia, then we would not expect to see evidence of Neanderthal admixture in these genomes given our current understanding of the Neanderthal geographic range. A conciliatory explanation for the fact that Australo-Melanesians have similar levels of Neanderthal admixture as other non-African populations has been proposed by Weaver, who has speculated that the Neanderthal genetic component present in Australasians may be the result of introgression from another group that was in direct contact with Neanderthals. ~

What DNA Says About Humans in Africa and Migrations 50,000 Years Ago

In paper on ancient DNA (aDNA) published in Nature in February 2022, Elizabeth A. Sawchuk, Jessica C. Thompson and others argue that every person on earth descended from hunter-gatherers in Africa and that ancient DNA reveals a massive social changes 50,000 years ago that shaped the way people today “living locally”. The team of researchers included a total of 44 members, who examine ancient DNA as far back as 18,000 years ago. [Source: Joshua Hawkins, BGR, March 9, 2022]

Joshua Hawkins wrote in BGR: Between 80,000 and 60,000 years ago, Homo sapiens spread beyond Africa to other landmasses. The study aimed to learn more about what happened after the spread. By looking at ancient DNA discovered in Africa, the team was able to determine several things. First, people changed how they moved and interacted around the time of the Later Stone Age transition. Roughly 30,000 – 60,000 years ago, the Later Stone Age transition is a prominent feature of the archeological record in African studies. Many consider it the origin or dispersal of “modern humans.” Based on the new aDNA they discovered, the researchers believe ancient people were descended from the same three populations. These populations are all related to present and ancient-day eastern, southern, and central Africans, the researchers say.

The researchers also found that something major happened around 50,000 years ago. This event changed how the people of Africa mixed and moved. Where the foragers had previously found partners away from their local areas, sometime around 20,000 years ago, most foragers in some regions were almost exclusively finding their partners in the local region. The researchers say this must have continued for some time, as the remains of ancient DNA didn’t appear to match with neighbors for several thousand years.

DNA Data Suggests Back and Forth, MultiRegional Migrations

Carly Cassella wrote in ScienceAlert: A genomic study led by researchers at McGill University and the University of California-Davis published in Nature in May 2023 suggests our family history isn't a single straight line tracing back through a slowly changing population, but a web connecting a diversity of families stretching across continents. The findings support a multiregional hypothesis, which argues that before our species left Africa for Europe, there was continuous gene flow between at least two different populations. The oldest fossils in Africa that resemble our own species were found in Morocco, Ethiopia, and southern Africa. But it's not clear which of these regions hosts the true cradle of humankind. [Source: Carly Cassella, ScienceAlert, May 2023]

"At different times, people who embraced the classic model of a single origin for Homo sapiens suggested that humans first emerged in either East or Southern Africa," explains population geneticist Brenna Henn from the University of California Davis.But it has been difficult to reconcile these theories with the limited fossil and archaeological records of human occupation from sites as far afield as Morocco, Ethiopia, and South Africa which show that Homo sapiens were to be found living across the continent as far back as at least 300,000 years ago."

Some researchers argue that's because we've been thinking about our human origins all wrong. Maybe the stem of our species is actually a braid of branches, created when a patchwork of co-existing populations migrate and mix. Genetic data seem to support that idea. Comparing the genomes of 290 modern-day people in South Africa, Sierra Leone, Ethiopia, and Eurasia, researchers found evidence of high gene flow between their ancestors in eastern and western Africa. They included genetic data from British individuals, to represent gene-flow back into Africa through colonial invasion, and a well-studied ancient Neanderthal genome from Croatia to account for genes from Neanderthals mixing with humans outside Africa.

Under a model of continuous migration, there could be two main lineages responsible for the genomes of those living in Africa today. These lineages represent distinct populations of early humans living in different parts of Africa around 400,000 years ago. Models suggest after evolving independently for a stretch of time on opposing sides of the continent, the two populations might have merged, ultimately fracturing into subpopulations that persisted from 120,000 years ago. "Shifts in wet and dry conditions across the African continent between 140,000 and 100,000 may have promoted these merger events between divergent stems," researchers write.

This intertwined lineage, they say, could have been the one to leave Africa for Europe around 50,000 years ago. Although, that's not exactly what the genomic data suggested. Compared to the genomes of those with European ancestry, models predict that the first humans in Africa left for Europe 10,000 years after they should have. Recent studies, however, suggest there may have been multiple waves of migration from Africa to Europe. Given the sparse fossil record for this time, genomic sequencing has become an incredible tool for scientists retracing the steps of our ancestors. The more genetic data experts read, the more complicated their story and ours becomes.

Ancient Arabian Stone Tools Hint of Multiple Migrations Out of Africa

Arabian stone tools from different periods of time tens of thousands of years ago hint of multiple migrations out of Africa. Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: To help shed light on the role the Arabian Peninsula might have played in the history of modern humans, scientists compared stone artifacts recently excavated from three sites in the Jubbah lake basin in northern Saudi Arabia with items from northeast Africa excavated in the 1960s. Both sets of artifacts were 70,000 to 125,000 years old. Back then, the areas that are now the Arabian and Sahara deserts were far more hospitable places to live than they are now, which could have made it easier for modern humans and related lineages to migrate out of Africa. "Understanding how we originated and colonized the world remains one of the most fascinating and enduring questions, because it is our story as humans," said lead study author Eleanor Scerri, an archaeologist at the University of Bordeaux in France. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, August 27, 2014]

"Far from being a desert, the Arabian Peninsula between 130,000 and 75,000 years ago was a patchwork of grasslands and savanna environments, featuring extensive river networks running through the interior," Scerri said. The northeast African stone tools the researchers analyzed were similar to ones previously found near modern-human skeletons. The scientists found that stone artifacts at two of the three Arabian sites were "extremely similar" to the northeast African stone tools, Scerri told Live Science. At the very least, Scerri said, this finding suggests that there was some level of interaction between the groups in Africa and those in the Arabian Peninsula, and might hint that these Arabian tools were made by modern humans.

Surprisingly, Scerri said, tools from the third Arabian site the researchers analyzed were "completely different." "This shows that there was a number of different tool-making traditions in northern Arabia during this time, often in very close proximity to each other," she said. One possible explanation for these differences is that the artifacts were made by different human lineages. Future research needs to uncover skeletal remains with ancient tools unearthed from the Arabian Peninsula to help solve this mystery, Scerri noted. Unless skeletal remains are found near such artifacts, it will remain uncertain whether modern humans or a different human lineage might have made them.

"It seems likely that there were multiple dispersals into the Arabian Peninsula from Africa, some possibly very early in the history of Homo sapiens," Scerri said. "It also seems likely that there may have been multiple dispersals into this region from other parts of Eurasia. These features are what make the Arabian Peninsula so interesting." Ancient migrants out of Africa and from Eurasia might have encountered a number of different populations in the Arabian Peninsula, Scerri said. Some of these groups may have adapted to their environment more than others had, which raises the intriguing question: "Did the exchange of genes and knowledge between such groups contribute to our ultimate success as a species?" Scerri said. The scientists detailed their findings online August 8, 2014 in the Journal of Human Evolution.

one view of the timing of the migration

Out of Africa and Back Again

Genetic analysis of a skull in Romania suggests that a group of early humans may have returned to the continent, leaving their mark on people there today. Bill Condie wrote: A new study of two teeth from a 35,000-year-old woman found in Pestera Muierii cave in Romania, show that at least some humans returned to the African continent. [Source: Bill Condie, Cosmos, May 21, 2016 ***]

“The discovery, published in the journal Scientific Reports, could explain why today’s North Africans are genetically related to people from Europe and Asia, as well as to other Africans. Scientists from the University of the Basque Country and University of Uppsala studied the mitochondrial genome of the Pestera Muierii woman, known as PM1. They found she belonged to a genetic group, or haplotype, called Basal U6 – one that many modern North Africans have descended from. ***

“Analyses of present-day human mitogenomes suggest that some populations initiated a migration back to North Africa around 45,000 years ago. However, the scarcity of remains in North Africa has prevented researchers from obtaining direct evidence of such a migration. "It was very surprising and interesting to find an individual this old carrying a U6 haplotype," Emma Svensson of the University of Uppsala told reporters. "Since the U6 haplogroup today is most common in North African populations we didn't expect to find it in such an ancient human from Romania."” ***

Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London wrote: “Another major difficulty in using DNA from modern individuals to the study of Out of Africa migrations is the high proportion of non-African ancestry in modern-day Africans. The first indicators of what is termed the “back to Africa” migrations were obtained from phylogeny and phylogeography of mtDNA haplogroups U6 and M1, which have an origin outside Africa and are currently largely distributed within North and East Africa. [Source: Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London, “Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate,” Evolutionary Bioinformatics, April 21, 2016 ~]

“There is now robust evidence for recent migrations back to Africa from non-African populations, as exemplified by high levels of non-African ancestry in present-day Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djbouti, and Somalia) and Southern Africa, where Eurasian ancestry proportions can be as high as 40%–50% in, for example, some Ethiopian populations. What is less clear, however, is both the number and the timing of these migrations, as there seems to be a lack of consensus among archeological, mtDNA, Y chromosome, and genomic studies. Using genome-wide data, back to Africa admixture into the Horn of Africa was dated using special software programs to around 3,000 years ago, coinciding with the origin of the Ethiosemitic languages. Others have argued for older, perhaps additional, back to Africa migrations using both autosomal and mtDNA analyses. Any such admixture complicates the ability to study the Out of Africa hypothesis using the genomes of modern day groups. For example, it is plausible that Eurasian gene flow into Africa, together with the high genetic drift reported for East Asians compared to Europeans, might explain the reduced African/European compared to African/East Asian divergence times mentioned in the previous work supporting multiple dispersals out of Africa. ~

“Intriguingly, the genome of a 4,500-year-old Ethiopian individual (thus predating the 3,000 years ago Eurasian backflow) named Mota has recently been published. Given that this specimen represents the first aDNA sample from Africa, it will likely become crucial for understanding African genetic diversity and accounting for confounding factors when using DNA from modern populations to reconstruct ancient events. However, the power to draw precise inference from a single such sample is likely limited, so that any resulting conclusions should be treated with caution.” ~

Candelabra Versus Multiregional Hypothesises

Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London wrote: “The debate dominating much of the anthropological discourse throughout the second half of the 20th century focused on where and when archaic hominins evolved into modern Homo sapiens, which we refer to as anatomically modern humans (AMH) throughout. Two main hypotheses dominated the discourse: the multiregional and the replacement hypotheses. The original multiregional model was proposed by the anthropologist Weidenreich in 1946 and advocated significant gene flow among subpopulations of Homo erectus living in different parts of the globe throughout the Pleistocene, so that modern humans trace their ancestry to multiple hominin groups living in multiple regions. Confusingly, the term “multiregional” model often has been used synonymously with the so-called candelabra model, originally proposed by Coon in 1962. [Source: Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London, “Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate,” Evolutionary Bioinformatics, April 21, 2016 ~]

Extreme splitter theory on evolution of Homo erectus to modern humans

“The candelabra model hypothesizes that our early hominin ancestors, after leaving Africa 1 million years ago and migrating to other continents, independently evolved anatomically modern features. Under this model, the modern human form arose autonomously at multiple times and locations worldwide within the last 1 million years, so that modern non-African populations each primarily descended from separate evolutions of these Homo species. This is in contrast to the traditionally proposed multiregional model, which importantly does not propose independent parallel evolution of Anatomically modern humans features. ~

“The main fossil evidence in support of the multiregional and candelabra hypotheses was the discovery of the Dali Man in China. For multiregionalists or candelabra supporters, the mixture of archaic and modern features was evidence of a midway stage between early and modern hominins. That said, these fossils are poorly preserved, and some authors have suggested that these anatomical characteristics are in fact shared by other Homo worldwide, and thus were not unique to Asia. Some genetic studies also offered support to a multiregional and candelabra models, inferring the origin of a few genetic loci outside of the African continent. Examples include the oldest haplotype in the human dystrophin gene, which was found to be absent in Africans, although this was later explained as resulting from adaptive introgression from Neanderthals rather than providing support for the candelabra model.” ~

Candelabra Versus Replacement (Out of Africa) Hypothesis

Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London wrote: “Opposition to the candelabra hypothesis has come from both paleontological and genetic studies. The replacement, or out of Africa (OoA), model proposes a single and relatively recent transition from archaic hominins to Anatomically modern humans in Africa, followed by a later migration to the rest of the world, replacing other extant hominin populations. Under this model, these hominins were driven to extinction, so that most of the genetic diversity in contemporary populations descends from a single or multiple groups of Anatomically modern humans who spread out of Africa sometime in the last 55,000–200,000 years, although debate remains on the precise timings (note that, in light of admixture from extinct hominin groups, the Out of Africa model is consistent with the original multiregional model but not the candelabra model). [Source: Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London, “Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate,” Evolutionary Bioinformatics, April 21, 2016 ~]

“The first genetic evidence consistent with the Out of Africa model was provided by the study of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) phylogenetic trees, which identified Africa as the source of human mtDNA gene pool. It was shown that all mtDNA haplogroups outside of Africa can be attributed to either the M or N haplogroups, which arose around 60,000–65,000 years ago in South Asia and are thought to descend from the L3 haplogroup postulated to have arisen in East Africa around 80,000 years ago. This was supported by further studies of mtDNA, Y chromosome, and autosomal regions that suggested the existence of a common African ancestor. More recently, multilocus studies of genome-wide data have demonstrated that genetic diversity decreases as a function of geographic distance from East or South Africa, for example, as shown by an approximately linear decrease in heterozygosity and increase in linkage disequilibrium (LD), a finding consistent with the Out of Africa model. ~

“Several further replacement models exist, which differ in their emphasis. Harding and McVean, for example, proposed a more complex meta-population system for the origins of the first Anatomically modern humans. The authors highlight evidence suggesting that the ancestral African population from which modern humans arose was genetically structured, so that extant populations at the time contributed unequally to the gene pool of individuals migrating out of the continent. The effects of ancient population structure on patterns of modern day genetic variation have also been suggested in several more recent papers, which assess the impact of ancient hybridization on modern day genetic diversity through modeling and data-driven analyses. In addition to genetic studies, structure in the ancestral African population has also been supported through archeological and palaeoenvironmental models. ~

Timing of Out of Africa

Modern humans first arose at least 300,000 years ago in Africa. When and how they dispersed from there has been controversial and a topic of fierce debate in the academic community, with geneticists suggesting the exodus started between 40,000 and 70,000 years ago but fossils, artifacts and archaeological evidence saying they left much earlier than that. Many scientists believe that Homo sapiens began migrated out of Africa between 50,000 and 150,000 years ago, replacing species that evolved from Homo erectus , including perhaps Neanderthals. There is strong evidence they reached Australia, at least by 65,000 years ago. A burial site that age has been found there.

Katherine Sharpe wrote in Archaeology: For years, archaeologists and geneticists have been troubled by the fact that their time lines for key events in human evolution don’t always match up. While archaeologists rely on the dating of physical remains to determine when and how human beings spread across the globe, geneticists use a DNA “clock” based on the assumption that the human genome mutates at a constant rate. By comparing differences between modern and ancient DNA, geneticists then calculate when early humans diverged from other species and when human populations formed different genetic groups. [Source: Katherine Sharpe, Archaeology, December 17, 2012 +||+]

“The DNA clock is a powerful tool, but its conclusions—for example, that modern humans first emerged from Africa about 60,000 years ago—can disagree with archaeological evidence that shows signs of modern human activity well before that date at sites in regions as far-flung as Arabia, India, and China.” A “revised clock also supports archaeological signs of modern human activity from more than 60,000 years ago at sites such as Jwalapuram, India and Liujiang, China—evidence that has often been dismissed by geneticists as impossible. While more work is needed to confirm the findings, Scally says that archaeologists who work on such sites should be excited: “It can no longer be said that the genetic evidence is unequivocally against them.”“ +||+ Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London wrote: “Currently, there are two conflicting proposals that dominate the literature, each differing by several tens of thousands of years and not mutually exclusive. The first claims that the Eurasian dispersal took place around 50,000 –60,000 years ago, reaching Australia by 45,000-50,000 years ago. The second posits that there was a much earlier exodus around 100,000 –130,000 years ago, prior to the eruption of Mount Toba (Northern Sumatra) dated to 74,000 years ago. [Source: Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London, “Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate,” Evolutionary Bioinformatics, April 21, 2016 ~]

“The Toba eruption is important in the context of dating the Out of Africa event, as stone tools thought to be associated with Anatomically modern humans have been found embedded in the volcanic ash. If these tools are indeed from anatomically modern humans, this provides clear evidence that modern humans had reached Southeast Asia before the Toba eruption more than 74,000 years ago. The stone tools discovered in the archeological site Jebel Faya (present-day United Arab Emirates) and the Nubian complex of Dhofar (present-day Oman) have provided further support for an early migration via Arabia. More importantly, the recent discovery of 47 human teeth in the Fuyan Cave in Daoxian (Southern China), dated to 80,000–120,000 years ago and unequivocally assigned to modern humans, supports the dispersal of Anatomically modern humans throughout Asia during the early Late Pleistocene. However, it remains to be seen if individuals among these groups contributed genetically to modern populations or represent another failed exodus similar to that proposed in the Levant, a question that DNA analyses are uniquely capable of shedding light on assuming genetic information can be interrogated reliably from these samples. Other pieces of archeological evidence that may help place Anatomically modern humans in the Far East over 70,000–120,000 years ago are the human remains from Zhirendong (South China), the teeth from Late Pleistocene Luna Cave, the famous Southern Chinese Liujiang skeleton, which seems to have anatomically modern features, and the Callao man, a human foot bone, discovered in Philippines that dates to 67,000 years ago.~

“Genetic studies have as yet been unable to settle the conflicting archeological evidence for these different dates, which can also be classified as pre-Toba (100,000–130,000years ago) or post-Toba (around 50,000–60,000 years ago). Given the lack of ancient DNA (aDNA) data temporally and spatially, such genetic-based approaches have focused on inference using modern DNA. Studies based on reconstructing mtDNA phylogenies have suggested a date for modern humans leaving Africa between 60,000-40,000 years ago, while dates inferred from STR analysis also fall within these estimates, positing an expansion date of around 50,000 years ago for central African, European, and East Asian populations. Time estimates from whole-genome sequencing data have been more variable and depend largely on the choice of model used. For example, studies using the allele frequency spectrum, identity-by-state, or coalescent-based models suggest a divergence time of 60,000–50,000 years ago, while analyses based on the pairwise sequencing Markovian coalescent (PSMC) model suggest that the divergence began 100,000–80,000 years ago, with gene flow occurring until 20,000 years ago. ~

“A key issue in the estimation of Out of Africa dates using autosomal data is that the Yoruba of West Africa are commonly used as the reference point for Anatomically modern human departure from East Africa, despite mtDNA and autosomal studies indicating a deep time separation of West and East African populations. Furthermore, many approaches assume that modern human groups are related via a simple bifurcating tree, which is likely an over simplistic view of human history. Another fundamental problem with many of the estimates used to date divergence times is that they are highly dependent on the choice of mutation rate, which can be estimated using a wide number of different approaches that often yield disparate values. The accumulation of heritable changes in the genome has traditionally been calculated from the divergence between humans and chimpanzees at pseudogenes, assuming a divergence time of around 6–7 million years ago (phylogenetic mutation rate 2.5 × 10−8/base/generation). With the advent of deep sequencing, it is now possible to directly calculate the mutation rate among present-day humans from parent-offspring trios. Using this method, the mutation rate has been estimated at 1.2 × 10−8/base/generation, half of the phylogenetic mutation rate, thus doubling the estimated divergence dates of Africans and suggesting that events in human evolution have occurred earlier than suggested previously. More recently, Harris reported that the rate of mutation has likely not been stable since the origin of modern humans, revealing higher mutation rates (particularly in the transition 5 -TCC-3 to 5 -TTC-3 ) in Europeans relative to African or Asian populations thus suggesting it may be too simplistic to assume the mutation rate is consistent across different populations. In addition to this, there is also considerable uncertainty in terms of the effect of paternal age at time of conception in the mutation rate with respect to ancestral populations. Recent work has attempted to mitigate some of these difficulties by instead calibrating estimates against fine-scale meiotic recombination maps. Using eight diploid genomes from modern non-Africans, Lipson et al calculated a mutation rate of 1.61 ± 0.13 × 10−8, which falls between phylogenetic and pedigree-based approaches. ~

“aDNA is becoming another major tool in appropriate calibration of mutation rate estimates and is likely to greatly refine our understanding of population divergence times, as it allows direct comparison of present-day and accurately dated ancient human DNA. For example, Fu et al used 10 whole mtDNA sequences from ancient Anatomically modern humans spanning Europe and East Asia from 40,000 years ago to directly estimate the mtDNA substitution rates based on a tip calibration approach. Using an amended mitochondrial substitution rate of 1.57 × 10−8, they dated the last major gene flow between Africans and non-Africans to 95,000 years ago. Later work utilized high coverage aDNA from a 45,000-year-old western Siberian individual called Ust’-Ishim and a technique based on modeling the number of substitutions in relation to the PSMC inferred history, which led to slightly higher estimates of 1.3–1.8 × 10−8 per base per generation. It is likely that an increasing availability of ancient samples from different time periods will assist in further refining these estimates.” ~

Origin of Modern Humans: Eastern or Southern, or Northern Africa?

Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London wrote: “Although the African origin of anatomically modern human is now largely accepted, debate has continued over whether the anatomically modern form first arose in East, South, or North Africa. Support for an East African origin is provided by the discovery of the [second] oldest unequivocally modern human fossils to date in Ethiopia: the Omo I from Kibish first discovered by Richard Leakey in 1967 dated to 190,000 and 200,000 years ago and the Herto fossils dated to between 160,000 and 154,000 years ago. [Source: Saioa López, Lucy van Dorp and Garrett Hellenthal of University College London, “Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate,” Evolutionary Bioinformatics, April 21, 2016 ~]

modern human sites in Africa

“Evidence for a Southern origin has largely been provided by genetic rather than archeological studies. Henn et al analyzed genomes from extant hunter-gatherers from sub-Saharan Africa: pygmies of central Africa, click-speaking populations of Tanzania in East Africa (Hazda and Sandawe), and the Khomani Bushmen of Southern Africa. Their analyses of LD and heterozygosity patterns suggested Southern hunter-gatherers were among the most genetically diverse of all human populations, lending support to a Southern African origin of anatomically modern humans.

“Schlebusch et al also considered patterns of LD in South Africa, observing the same high levels of genetic diversity, low levels of LD, and shorter runs of heterozygosity as mentioned in the previous studies. However, by incorporating additional samples throughout the rest of Africa, they showed that LD-based statistics fail to pinpoint a specific origin point, as LD levels were similarly low in other parts of the continent besides South Africa, indicating that different groups of individuals within different regions are important. This suggests that the population history within sub-Saharan Africa is likely too complex to localize the origins of H. sapiens using these approaches and available data. Similarly, Pickrell et al showed an ancient link between the Southern African Khoe-San and the Hadza and Sandawe of East Africa, suggesting that both Eastern and Southern Africa are equally consistent candidates as an origin locality of modern humans. ~

“A more recent study jointly analyzed paleo-climatic records and estimates of effective population size from the whole-genome sequences of five Khoe-Sans and one Bantu individual along with 420,000 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) from worldwide groups. Although unable to resolve a Southern or Eastern origin, using coalescent-based modeling, they suggest that Southern African populations have had high effective population sizes throughout their history, which might result in lower levels of LD relative to other parts of Africa, irrespective of where Anatomically modern humans arose. This corresponds well with climatic records, which find that Western and central Africa were affected by a dry climate with increasing aridity, around 100,000 years ago, leading to a decline in the effective population size of West African populations (ancestors of the Bantu-speaking and non-African populations) but not vastly altering the effective size of South Africans (ancestors of the Khoe-San). The incorporation of climatic data has also been important in mtDNA analyses aiming to resolve a clear location of origin. In a paper focusing on the distribution of mtDNA haplogroups, Rito et al propose that the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of modern mtDNA likely arose in Central Africa before splitting into Southern African groups such as the Khoe-San (L0) and central/East African groups (L1’6). This is in good agreement with the aforementioned autosomal studies, which postulated an early split between the Khoe-San and more Northern African populations, although they did not advocate a MRCA in Central Africa. ~

Jebel-Irhoud skull

Up until recently, little focus has been given to North Africa as a potential origin point of the Anatomically modern human form, despite the discovery of early anatomically modern humans, Jebel Irhoud remains in Morocco dated to 160,000 years ago [and 300,000 years ago], Focus on the region changed with the publication of a revised Y chromosomal phylogenetic tree based on resequencing of male-specific regions of the Y chromosome from four relevant clades. The revised phylogeny found that the deepest clades were rooted in central and Northwest Africa, suggesting this region was more important than previously thought. Fadhlaoui-Zid et al went on to analyze both Y chromosome and genome-wide data from North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. They found some evidence for a recent origin of human populations in North Africa but stressed how high levels of migration, admixture, and drift in North Africans make interpretation extremely challenging. ~

“It is important to note that many genetic-based approaches such as these are limited in their ability to answer questions of this nature given that extant human populations are likely poor representatives of populations residing in these regions during pre-Anatomically modern human time periods. For instance, populations can be quite mobile, and thus the geographic location of modern humans groups may differ from that of their ancestors in the past. Archeological and paleontological approaches, as well as DNA from ancient human remains, can go some way to guiding inference but are also limited given the scarcity of sites. For example, an origin of Anatomically modern humans in Western or central Africa cannot be ruled out but to our knowledge, there is currently no archeological data available to address this as a candidate region.” ~

World’s Oldest Modern Human Fossils Found in Morocco

Our concept of human origins was thrown for a major loop in 2017 with the announcement of the discovery of modern human fossils, dated to 300,00 years ago, about 100,000 years older than any other known remains of our species, Homo sapien, in an old mine on a desolate mountain in Morocco. Both the date of the fossils — skulls, limb bones and teeth from at least five individuals — and their location were surprises — “a blockbuster discovery.” [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, June 8, 2017 ^]

Will Dunham of Reuters wrote: “The antiquity of the fossils was startling - a “big wow,” as one of the researchers called it. But their discovery in North Africa, not East or even sub-Saharan Africa, also defied expectations. And the skulls, with faces and teeth matching people today but with archaic and elongated braincases, showed our brain needed more time to evolve its current form. “This material represents the very root of our species,” said paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, who helped lead the research published in the journal Nature.

“Before the discovery at the site called Jebel Irhoud, located between Marrakech and Morocco’s Atlantic coast, the oldest Homo sapiens fossils were known from an Ethiopian site called Omo Kibish, dated to 195,000 years ago. “The message we would like to convey is that our species is much older than we thought and that it did not emerge in an Adamic way in a small ‘Garden of Eden’ somewhere in East Africa. It is a pan-African process and more complex scenario than what has been envisioned so far,” Hublin said. ^

“The Moroccan fossils, found in what was a cave setting, represented three adults, one adolescent and one child roughly age 8, thought to have lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. These were found alongside bones of animals including gazelles and zebras that they hunted, stone tools perhaps used as spearheads and knives, and evidence of extensive fire use. An analysis of stone flints heated up in the ancient fires let the scientists calculate the age of the adjacent human fossils, Max Planck Institute archaeologist Shannon McPherron said. ^

Genetic Evidence of the Out of Africa Theory of Modern Men

Qafzeh skull from Israel

Chinese researchers Feng Zhang, Bing Su, Ya-ping Zhang and Li Jin wrote in an article published by the Royal Society: “ The ‘out of Africa’ hypothesis asserts that modern humans originate from an ancestral population in Africa, which expanded and spread out of Africa and completely replaced archaic human populations (H. sapiens or H. erectus) outside Africa (Cann et al. 1987; Wilson & Cann 1992). Some anthropologists have claimed that anthropological evidence in China supported a regional evolution from H. erectus to modern human (Wu 1988). However, the phylogenetic tree of human mtDNA variations suggested that the ancestor of modern humans came out of Africa (Cann et al. 1987). From then on, more and more genetic data have been accumulated, most of which supported the out of Africa hypothesis (e.g. Bowcock et al. 1994; Hammer 1995; Tishkoff et al. 1996; Chu et al. 1998; Quintana-Murci et al. 1999; Su et al. 1999; Ingman et al. 2000; Ke et al. 2001). [Source: “Genetic studies of human diversity in East Asia” by 1) Feng Zhang, Institute of Genetics, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, 2) Bing Su, Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, 3) Ya-ping Zhang, Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Bio-resource, Yunnan University and 4) Li Jin, Institute of Genetics, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University. Author for correspondence (ljin007@gmail.com), 2007 The Royal Society ***]

As the mtDNA data supporting the out of Africa hypothesis were formerly restricted to the control region and RFLP in the coding region, Ingman et al. (2000) utilized the complete mtDNA sequences of 53 humans of diverse origins in tracing human evolution. As before, the newly generated mtDNA phylogeny indicated an African origin of modern humans (Ingman et al. 2000). ***

By analysing the markers on NRYs in over 1000 male individuals, Underhill et al. (2000) constructed a parsimonious genealogy to trace the evolution of modern humans. According to the phylogenetic tree, all the tested men from outside Africa share the same mutation (M168), which arose in Africa between 35 000 and 89 000 years ago. There are three parallel mutations (M89, M130 and Y Alu polymorphism, YAP) downstream of M168. Ke et al. (2001) examined these markers in 12 127 men from 163 populations in Asia and found that every sample had inherited one of these markers. This finding indicates that all of them are descendants of a relatively recent common ancestor in Africa, which supports a complete replacement of local archaic populations by modern humans from Africa from the perspective of paternal lineages. ***

Migration of Early Modern Humans Out of Africa

DNA studies of people living today indicate that modern humans migrated from Eastern Africa to the Middle East, then Southern and Southeast Asia, then New Guinea and Australia, followed by Europe and Central Asia. Perhaps they didn't enter Europe because that region was dominated by Neanderthals. According to research by geneticist at the University of Cambridge in the mid 2000s all modern humans descend from a small number of Africans that left Africa between 55,000 and 60,000 years ago. Another DNA less reliable study determined that an intrepid group of 500 hominids marched out of Africa about 140,000 years ago and they are the ancestors to all modern people today. [Source: Guy Gugliotta, Smithsonian magazine, July 2008]

These studies are based on genetic variations found in different population groups. People in sub-Saharan Africa have more genetic variation than non-Africans. The number of people and the date for the 140,000 year figure was arrived by studying genetic variations in 34 populations around the world, coming up with a rate of genetic change and extrapolated back in time. The fact that people in sub-Saharan Africa have more genetic variation than non-Africa indicated humans that have lived in Africa have lived there longer than other people have lived in their homelands.

The earliest known mutation to spread outside Africa is M168, which developed about 50,000 years ago. It is found in all non-Africans. M9 is a marker common in Eurasians. It appeared in the Middle East or Central Asia about 40,000 years ago. M3 is a marker that developed among Asian people around 10,000 years ago and reached the Americas.

Based on genetic evidence gathered by National Geographic magazine and scientists from around the globe it has been determined that modern humans originated in southern Africa around 200,000 years ago and made to West Africa about 70,000 years ago and the Middle East about 50,000 years ago, advancing rapidly through southern and southeast Asia and reaching Australia also around 50,000 years ago but not reach East Asia and Siberia until 30,000 years ago and southern Europe until 20,000 years. From Siberia modern humans reached North America about 15,000 years ago and migrated southward reaching South America between 13,000 and 15,000 years ago. The group living today with the closest links to our 200,000-year-old ancestors in southern Africa are the Khoisan hunter-gatherers of southern Africa. [Source: National Geographic, November, 2009]

Some scientists feel the migration out of Africa was also accompanied by revolutions in behavior and technology such as more developed social networks and advanced tools and sophisticated language that gave them ability to prosper in new lands and in some cases drive out hominids that already lived there.

migration routes in Asia 33,000 to 19,000 years ago

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Africa sites, Science magazine, and Middle East migration routes, researchgate.com

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024