THE LEAKEYS

Louis Leakey Dr.Louis Leakey, his wife Mary, their son Richard and his wife Meave have made some of the greatest discoveries in the study of early man. Louis used to ascribe his great achievements and finds to "Leakey's Luck." Almost as important as their discoveries were the publicity and prestige they gave to their field.[Source: Melvin M. Payne, National Geographic, February 1965].

Donald C. Johanson, director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University wrote in Time magazine, the Leakeys “dominated anthropology as no family has dominated a scientific field before or since." In to their work they inspired a whole generation of scientists like Jane Goodall, Diane Fossey and Biruté Galdikas — who did pioneering work with chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans — and many of the leaders in the study of early man such as Johanson, the discoverer of Lucy.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Fossil Men: The Quest for the Oldest Skeleton and the Origins of Humankind” By Kermit Pattison (2021) Amazon.com

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Born in Africa: “The Quest for the Origins of Human Life” by Martin Meredith Amazon.com;

“Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Humankind's Beginnings” by Virginia Morrell Amazon.com;

“Disclosing the Past”, Mary Leakey’s 1984 autobiography Amazon.com;

“The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the Past” by Meave Leakey with Samira Leakey (2020) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Masters of the Planet, The Search for Our Human Origins” by Ian Tattersall (Pargrave Macmillan, 2012) Amazon.com;

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Talk Origins Index talkorigins.org/origins ; Last updated 2006. Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Human Evolution Images evolution-textbook.org; Hominin Species talkorigins.org ; Paleoanthropology Links talkorigins.org ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution; Fossil Sites and Organizations: Institute of Human Origins (Don Johanson's organization) iho.asu.edu/; The Leakey Foundation leakeyfoundation.org; Turkana Basin Institute turkanabasin.org; Koobi Fora Research Project kfrp.com; The Paleoanthropology Society paleoanthro.org;

Quest for the Origins of Human Life in Africa

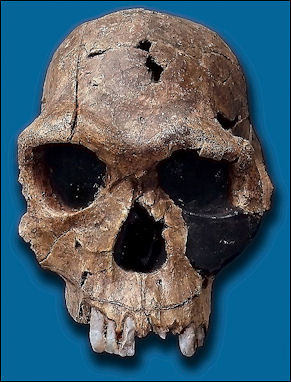

In a review of the book “Born in Africa: The Quest for the Origins of Human Life” by Martin Meredith, Rachel Newcomb wrote in the Washington Post, “In 1924, anatomy professor Raymond Dart came across an unusual skull that a mining company had inadvertently blasted out of a hillside in a South African village. Despite its small brain size, the Taung Child, as the skull was to be named, had distinctively human features, including signs that its owner walked upright. But Dart’s finding contradicted prevailing scientific opinion, which held that the evolution of a large brain preceded other human adaptations, such as walking. Confirming this belief was the 1912 discovery of Piltdown Man, a skull found in a gravel pit in Piltdown, England. With its large cranium but otherwise apelike features, Piltdown Man supposedly represented the missing link between primates and humans, proving that humans came out of Asia and not Africa. [Source: Rachel Newcomb, Washington Post, July 14 2011]

Dart disagreed, and he enthusiastically published his findings. Yet the conservative scientific establishment savaged him, arguing that he had misidentified a mere primate. Among Dart’s other crimes were failing to follow proper research protocol and using “a “barbarous” combination of Latin and Greek in naming the specimen Australopithecus.” After this professional drubbing, Dart suffered a nervous breakdown, and the Taung skull languished for years as a paperweight on the desk of a colleague.

Twenty-three years later, Robert Broom, a maverick fossil hunter and physician who conducted his South African excavations under the blazing sun dressed “in a dark suit and waistcoat, long-sleeved white shirt, stiff butterfly collar and somber tie,” made his own discovery of an australopithecine, finally vindicating Dart. In 1953, scientists confirmed that Piltdown Man had been an elaborate 40-year hoax, a skull patched together from a combination of human and orangutan remains and artificially distressed to appear ancient. The Piltdown skull was only a few hundred years old; the Taung Child, however, was eventually dated at 2.7 million years. Broom’s discoveries finally turned the tide of scientific opinion toward accepting humanity’s origins in Africa.

In Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge, where Mary Leakey first spotted the 1.75 million-year-old skull she referred to affectionately as “Dear Boy,” researchers battled black dust clouds, drought conditions and incessant sun while also having “to contend with marauding lions, rhinoceroses and hyenas.” Later, Richard Leakey’s team found a 1.6 million-year-old, nearly complete skeleton in Kenya’s Lake Turkana, which “resembled a lunar landscape, a boundless expanse of lava and sand littered with the wrecks of ancient volcanoes. The winds and the heat were ferocious.”

Fossil hunting was an arduous and frequently unrewarding business. Sometimes years would pass with no discoveries at all as researchers scrambled to acquire funding and government permits. Although Meredith gives credit to native fossil hunters who unearthed noteworthy finds, the scientists, many of whom were skilled at self-promotion, take center stage. At the start of new fieldwork in Koobi Fora, Kenya, for example, Richard Leakey, “with romantic notions of himself as a heroic explorer riding across the African desert,” hired camels and let the cameras roll. In 1974, when Leakey’s American rival Donald Johanson announced his discovery of the 3.2 million-year-old australopithecine known as Lucy, he shouted on camera, “I’ve got you now, Richard!” Outsized personalities, turf wars, public insults and heated debates were the order of the day.

Book: "Born in Africa: The Quest for the Origins of Human Life” by Martin Meredith (PublicAffairs, 2011]

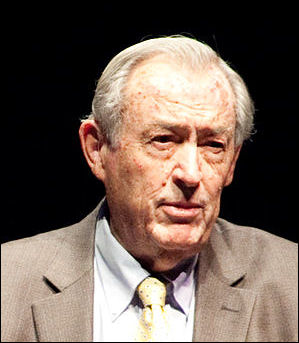

Louis Leakey

“More than anyone, Louis Leakey established paleoanthropology as a high profile endeavor.” Roger Lewin wrote in Smithsonian magazine. “By the time he died...his name had become synonymous with the search for human origins. A passionate naturalist and an astute chronicler, Leakey was also a showman who tirelessly publicized his discoveries to admiring audiences around the world.”

Leakey was not only a famous anthropologist and paleontologist he was skilled in zoology, archaeology, and anatomy and conducted a medical dispensary for African tribesmen when in the field. In addition to his numerous publications on prehistory and anthropology, he wrote of books on Kikuyu customs, language, and grammar.

Leakey “pursued a breathtaking range of interests,” Lewins wrote. “He studied fossil bones, stone artifacts and cave paintings. He published monographs on the social customs of the Kikuyu people of Kenya and the string figures, comparable to cat’s cradles., made by people of Angola...Long before wildlife conservation became popular, Leakey helped establish national parks in Kenya. He was an expert stone knapper, or tool maker, and would delight in making sharp implement with which he would swiftly skin an animal when ever he had an audience, His knowledge of animal behavior was encyclopedic , and he was a keen ornithologist, which he had once thought would be his career.”

In World War II, Leakey ran a British spy network against the Germans in East Africa. Later he helped the British gather intelligence during the Mau Mau uprising. Convinced that study of primates could offer insight into ancient man he established a research center for the study of primates near Nairobi. Leakey recruited Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, Biruté Galdikas as "as if he were Paris handing Aphrodite the prized apple" wrote Leakey biographer Virginia Morell. Louis died in 1972 in London at the age of 69.

Book: “Ancestral Passions” by Virginia Morrell (Simon & Schuster).

Louis Leakey's Parents and Early Life

Olduvai Gorge Leakey was born in Kabete in colonial Kenya in 1903 in a mud-walled bungalow. Pictures of the house show it draped with a tarpaulin. The original thatch roof of the mansion-sized home often failed during torrential downpours.

Leakey's parents were Anglican missionaries, who ran a mission northwest of Nairobi. His mother, Mary Bazett, came to Africa in 1892, only 21 years after Stanley and Livingstone met on the shores of Lake Tanganyika. She was one of 13 children of a British Army colonel living in Reading, a quiet suburb of London, and came to Africa with three of her sisters to work as a missionary.[Source: Melvin M. Payne, National Geographic, February 1965]

After she had been in Kenya for a while Mary's sister Nellie resolved that she was going to travel some 700 trackless miles to Uganda. She was denied permission by the British commissioner to undertake the journey so she up a left on her own with a group of porters. "Her only weapons on the safari," Dr. Leakey said, "were an umbrella and an alarm clock. She'd set the alarm at two hour intervals throughout the night. She reckoned that a prowling lion would require at least two hours to reconnoiter before entering the camp, at which time the clanging of the alarm would frighten him off. All the way to Uganda she slept in two hour naps."

Meanwhile back in Mombasa Mary fell ill and was ordered back to England and was advised never to return to Africa for it might kill her. While in England she married another missionary — Harry Leakey, Louis Leakey's father — and returned to Kenya, where she remained until she died 50 years later. Harry and Mary Leakey took over a Church of England mission in Kabate, eight miles north of a tiny upcountry settlement known as Nairobi. There they began to work among the Kikuyu and there Leakey and his brother and two sisters were raised.

Louis Leakey and the Kikuyu

When Leakey was born the Kikuyu tribal elders gather around his cradle and spit on the newborn child as a gesture of trust. "The Kikuyu," Louis later explained, "believe that to possess part of another person — a fingernail, a lock of his hair, even his spittle — gives one the power to work deadly black magic against him. Symbolically, the elders were putting their lives in my hands...The elders made me the best washed baby in East Africa.” [Source: Melvin M. Payne, National Geographic, February 1965] Leakey was brought up among the warriors of the Kikuyu tribe. "We call him the black man with the white face,” a tribal chief once called him because they regarded him as more African than European. The tribesmen taught Leakey how to coax a swarm of bees into a hive; how to trap animals sold to European zoos; and how make snares. He sharpened his spear throwing skills aiming at hoops made of twigs. By the time he was 13 he lived in his own thatched hut which he built himself with the help of his Kikuyu brothers and lived in it whenever his parents allowed. Leakey claimed, even when he an old man, he often thought and dreamt in Kikuyu.

In 1937 Kikuyu elders initiated Leakey into the tribe. At this time he was initiated into the tribe and given the name "Wakaruigi"’son of the Sparrow Hawk." Even his wife Mary didn't know the details of the initiation ceremony. Leakey swore an oath of secrecy and even during the Mau Mau troubles when the Kikuyu were not very popular among the Europeans he kept his word. As far as anybody knows Leakey was the only white man ever to become initiated as a Kikuyu.

Leakey listened to many stories from the Kikuyu elders around the village campfires. The lessons of many of the stories were two things: patience and observation, two virtues that paid off later in his search for clues of prehistoric man.

Louis Leakey and Animals

Olduvai Gorge hand ax Louis was taught how to how to hunt and stalk game by an old hunter from the Dorobo tribe. The Dorobo hunt with short range weapons — clubs, arrows, stubby spears’so success hinged on getting as close possible to the animal before attacking. Leakey learned that small antelope like the duiker do not easily distinguish motionless objects. A hunter therefore camouflages himself with boughs and leaves to break up the outline of his body. Then, from down wind he commences his cautious approach. He advances from an oblique angle — a direct stalk would send the duiker darting into the underbrush. Slowly the hunter draws near. The duiker can glance up, and look right at the hunter, but if the doesn't move or show his hands often the small antelope won't notice him. When the hunter gets close enough he hurls his spear for the kill. [Source: Melvin M.Payne, National Geographic, February 1965]

Leakey also learned to catch ducks by placing moss over his head and sitting in a lake, pretending to be a tree stump. When the ducks weren't looking he'd amble over to where the ducks were. If he got close enough he'd try to grasp their legs. "In Africa," Louis once said, "Everything depends upon your reaction to irregularities in your surroundings. A torn leaf, a paw print, a bush that rustles when there is no breeze, a sudden quiet — these are signals that spell the difference between life and death."

Louis used to enjoy putting himself in the minds of the animals he observed. Once when he saw a lion approaching a group of zebras, taking the point of view of the lion, he muttered softly, "There they are, but I must be careful...take to the ravine, quicklyt...slowly now...they're looking up...all right, get behind the clump...there...a few years more and...Shit!" a Land Rover approached, honking it horn, scattering the zebra.

Leakey used to advise visitors to his camp, "If you hear any animals sniffing or snorting around your tent during the night “or even if a lion should pay a visit and make a lot of noise — just stay in you blankets and be quiet. He's really not looking for you and won't bother you if you don't bother him." Leakey once clubbed to death more than 50 venomous krait snakes around his camp in six weeks. He used rifles shots and firecrackers to keep lions away from his camels. Oncea lions caught a zebra 15 meters from his tents and no one heard it.

Leakey's Early Career as a Paleontologist

A. boisei Growing up Leakey received a formal education from his parents. When he was 16 he went to public school in Britain, where he described himself as “shy and unsophisticated and out touch with the English way of life.” Two years later he entered Cambridge University, his farther’s alma mater, and earned a degree in archaeology and anthropology. The first fossil collecting expedition Leakey went on while still a student was led by a Canadian paleontologist who died from a combination of malaria, dysentery and typhoid.

When Leakey told one of his professors that was interested in searching for ancient man in Africa, his professor said. “There’s nothing of significance to be found there. If you really want to spend you life studying early man, do it in Asia — where Java Man and Peking Man had been discovered. Leakey returned to Africa in spite the advise. “I was born in Africa,” he later wrote, “and I’ve already found traces of early man there. Furthermore, I’m convinced that Africa not Asia is the cradle of mankind.”

As a paleontologist, Leakey was largely self taught. His first great find, in Kariandusi, Kenya, occurred in 1931, on his third expedition to Africa, after he almost fell of the edges of a cliff hidden by vegetation. As he clutched at bushes to save himself, the story goes, he espied an ax embedded in the wall which turned out to be 200,000 years old. Later he discovered that men who lived around the same place used bolas, similar to those of Argentine gauchos. [Payne, Op. Cit]

Sloppy science however kept him from being taken seriously. A skeleton he presented as proof that ancient man was far older than had been previously thought turned out to have been buried at a later date in old sediments. A jawbone found at the Kanam site in western Kenya which claimed was “not only the oldest human fragment from Africa, but the most ancient fragment of true “Homo” yet to be discovered anywhere in the world” turned out to be much more recent than he claimed.

Leakey once said, "To an inexperienced eye, as I soon learned, fossil bones, stone tools, and plain rocks can sometimes look distressingly alike." His reputation was undermined further when a geologist visited Kanam and found that Leakey wasn’t exactly sure where he jaw had been found.

Leakey's Character

Olduvai stone

chopping tool Leakey was charming and gregarious. He was a charismatic lecturer, a skilled fundraiser and seeker of publicity and limelight. His son Richard told Smithsonian magazine, “He loved to be recognized and to stimulate people by talking about what he’d done and who he was.” Andrew Hill, a professor of anthropology at Yale, told Smithsonian, “Everything Louis did, he did with enthusiasm. He’d even be enthusiastic about the breakfast he prepared or the dinner he cooked. It could get a little wearing, especially at breakfast if you weren’t a morning person.”

Donald Johanson wrote in Time, Leakey had a "staccato-like voice, punctuated by rapid inhales. He cast a spell, making each listener believe he was speaking to him or her.” He was “sharing his passion , knowledge and intuition...he was often like that: generous, open, supportive, always trying to win new converts."

Leakey’s supporters followed him with cultlike devotion. Mary Smith of the National Geographic Society, which supported Leakey’s work, said “he could charm the birds out of trees.” he “had a way of making even the littlest, most unimportant person feel important. That’s why people were so willing to work for him.”

Many women were attracted to him. Recalling his first encounter with him, Harvard anthropologist Irven DeVore told Morell, “he was dressed in one those awful boiler suits, and had a great shock of unruly white hair, a heavily creased face and about three teeth...When my wife, Nancy and I got back to our hotel, I said to her, he must be one of the ugliest men I ever met.” And she said, “Are you kidding? That’s the sexiest man I’ve laid eyes on.” Leakeys was not immune to exploiting the spell the cast; his philandering soured both of his marriages.”

Many in the academic community though regarded Leakey as "impulsive and cavalier in his pronouncements” and being “anything but typically English.” Many of his bold claims turned out to be wrong and he had a habit of announcing new theories before all the evidence was in. But while he scorned bookish academic who spent little time in the field he wanted desperately to be accepted as a serious academic and be elected as a fellow to the Royal Society, Britain’s most prestigious scientific organization, an honor that eluded hm.

Louis Leakey and His Discoveries

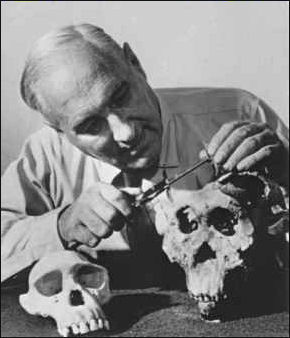

Homo habilis Leakey and his family made some of the greatest discoveries in the history of anthropology and paleontology. The so called "Leakey's Luck" of his "Hominid Gang" has been attributed to energy, determination, persistence, optimism and an excellent field team. But although it was Louis he often grabbed the headlines and was snapped by photographer it was his wife Mary, a trained archaeologist, who made most of the discoveries associated with the Leakey name.

Before Leakey came along, scientists believed that man first evolved in Asia, where Peking Man and Java Man were discovered. Leakey placed the origins of mankind in Africa, view that most scientists share today. The Leakeys are also credited with starting "the truly scientific study of the evolution of man."

The first great Leakey discovery occurred in 1948: the skull of an 18-million-year-old ape, the first fossil ape skull ever found. When the skull was brought to England, a mob of reporters greeted Louis and Mary at the airport. On the skull, Mary said, “Two plain clothes detectives assigned to guard it never let it out of their sight.”

The discovery of the “Zinjanthropus” skull at Olduvai Gorge in 1959 was the Leakey’s finest hour from a publicity point of view (See Australopithecus boisei). Although Mary was the one who discovered Zinjanthropus Louis got most of the acclaim. This is the discovery that made the Leakeys a household name and gave them a comfortable financial support from the National Geographic Society.

In 1964, the Leakeys unveiled “Homo habilis” (handy man), one of the most significant discoveries in the study of ancient man. The first “Homo habilis” fossil found was a jawbone discovered by 19-year-old Jonathan, the eldest of the Leakey’s three sons, in 1960 near where the Zinjanthropus skull was found. More searching at Olduvai revealed more “Homo habilis” bones. When the new fossils was unvealed to the public they were greeted with as much contempt as enthusiasm, especially because the Leakey’s had the gaul to attach the name “Homo” to the new species, thus claiming it was a direct ancestor of humans.

In addition to bones of prehistoric humans, Leakey also found fossils of giant dogs and ostriches, rhino’s three times as large as those found today as well as 25 million-year-old beetles, slugs and caterpillars that were as life-like as the real thing. He even found the head of a large lizard whose tongue was still striking out of its mouth and the eyeballs were perfectly preserved. Among Leakey’s claims was finding the found the world's oldest known structure, a two million year old windbreak, at in Olduvai Gorge.

Many of Leakey’s later “discoveries” were dubious at best. In the 1960s he claimed that 20-million -year-old apes bone he unearthed were the oldest hominin fossils every found and made similar claims about some 14-million -year-old ape bones he named “Kenyapithecus wickeri”. His most outlandish claim came in 1967 when he announced at a scientific meeting that a lump of lava he found near Lake Victoria was a tool used “Kenyapithecus wickeri”. The announcement was so out of the realm of what was possible not a single question as asked. Equally outrageous was his claim that stone flakes found in the Calico Hill outside Los Angeles were 100,000 years old. The prevailing view then as it now is that humans didn’t arrive in the Americas until 30,000 years ago at the earliest.

But despite all this Leakey’s lasting legacy on the study of early man can not be underestimated. Penn State’s Alan Walker told Smithsonian magazine, “Although Louis was not highly regarded for his science he made a major contribution in opening up east Africa for paleoanthropological exploration, making the science possible.” David Pilbeam, a professor of anthropology at Harvard, said, “he had an energizing effect on the field and on the people doing the research. He could be sloppy and brillian, prescient and foolish. But given the time [in which] he was working, overall his instincts were right.”

Leakey Fossil Collecting Stories

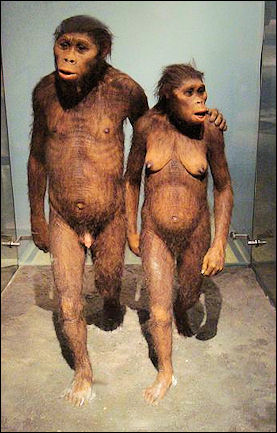

Laetoli recreated On looking for fossils with wild animals around, Leakey said, “We're never armed...Any lion before he charges will roar and twitch his tail violently.... If we weren't subconsciously alert to animals and their wits, we probably would have been dead long ago. You only stumble across a lion with its kill once. Or a touchy rhino shepherding its young."

The Leakeys used to keep dalmatians on hand at their digs to warn them of approaching lions, leopards, snakes and other dangers. For a while at their camp the Leakey's had a baby wildebeest, a squirrel, horses, cats, four duiker antelopes, Simon, their pet monkey, and a turkey "rescued from a holiday meal." [Source: Louis B. Leakey, National Geographic, January 1963]

One time Leakey got stuck in a storm in a leaky boat six miles from shore in Lake Victoria. "We used cups, saucers, even my cloth hat to bail with, ," he said, "but as the waves hammered the hull, more stitches parted, and soon the water was coming in faster than we could bail. I began to think about our chances. In those days the waters of Lake Victoria were infested with vicious crocodiles...My crew obviously had the same depressing thoughts, for suddenly, while still bailing frantically, they began to make verbal wills among themselves...'If I drown and you don't,' one man said to his companion, 'tell my wife to give two cows to so-and-so to pay off our debt. And tell her there is money in the secret hiding place and she must use it'...It was hardly reassuring...But then, just as suddenly as the storm had struck it passed, and...somehow we managed to work the canoe, now completely awash, to...bring it ashore.”

The Leakeys had occasion run ins with the Masai. Even though they built two cattle-watering dams for the Masai in return for the Masai staying out of Olduvai Gorge with their cattle, the Masai came in away and crushed a million-year-old hominin skull. The skull was salvaged by sifting through the sand to get all the pieces. It turned out to be one of the Leakey’s greatest finds. After that a better deal was struck with Maasai: if they stayed out of the gorge a third dam would be built, if they intruded again the other two dams would be destroyed. A couple of young warriors discovered to be the intruders were beaten by other tribesmen with sticks.

Mary Leakey

Mary Leakey Described as the "grande dame of archaeology," Mary Leakey smoked cigars and drank whiskey into her 80s and loved dalmatians. In contrast to her husband Mary was shy, reserved and in her own words "not very fond of other people” but is said to have had a great sense of humor.

Her son Richard said, "Louis was always the better publicist. But Mary was the centerpiece of the research." Her daughter-in-law, Meave Leakey told the New York Times, "With Louis and Mary, Mary was the person who did the detailed work, Louis was the organizer, the effervescent fund-raiser, the public person."

Mary was a careful and thoughtful scientist. "Theories come and go," she once said, "but fundamental data always remains the same." In 1959, Mary was one who discovered Zinjanthropus. In 1978, after Louis had died, her team made one of the greatest discoveries in the study of ancient man, the 3.6 million year old foot prints from Laetoli, Tanzania that proved without a doubt that man walked upright at that time. Mary Leakey retired in 1984. She died at the age of 83 in December, 1997.

Mary Leakey was born Mary Nichols. She was an artist and archaeology student, who became entranced with Louis Leakey after attending one of his lectures. which she originally did not want to attend. In 1933, she was asked by Leakey to illustrate his book. Later she accompanied him to Olduvai Gorge. Louis deserted his first wife Frida, while pregnant with her and Louis’s second child, to marry Mary in 1936.

Angered by her husband’s womanizing and some of his wild claims, Mary was estranged from Louis in the last years of his life. While he spent his time traveling around the world, lecturing and fundraising, Mary camped and worked at Olduvai Gorge for 25 years with her staff and dogs. In her autobiography she blamed Louis’s dubious “discoveries” as “catastrophic to his professional career and...largely responsible for the parting of our ways.”

Book: Mary Leakey’s 1984 autobiography is called “Disclosing the Past” .

Louis and Mary Leakey's Children

Richard Leakey Leakey's three son were just as colorful as Leakey himself. Philip, the youngest, was a master at blazing trails through the bush with a Land Rover when he was 12 years old; Jonathan, the oldest became a herpetologist (a snake biologist); and Richard followed in his father's footsteps and became an anthropologist. He also became head of the Kenyan Wildlife Ministry, where he played a key role in turning the tide on poaching in Kenya's parks. [Source: Melvin M. Payne, National Geographic, February 1965]

Jonathan spent a good part of his early career milking poisonous snakes of their venom and selling it to laboratories in South Africa. He used to milk up seventy snakes a day by placing the snake's mouth up to a jar and then massaging its head to get the fangs to extend out and release their venom.

Once Jonathan was bitten by a deadly viper that twisted around in hand and struck his finger. The venom was know to kill within minutes. To save himself Leakey slashed the wound and sucked out the blood and gave himself an injection of antivenin. While he lay on the floor faint and shaking he took notes of his reaction. His father discovered him. "You see," Louis said, "the literature contained nothing about the bite of this particular snake...so I wrote down everything he said. Things like 'my heart's beating very fast...faster still. The headache is much worse. Now I feel dizzy.' He wanted to be sure that his reactions were recorded at the time and not from memory."

Richard Leakey

Lake Turkana Richard Leakey was born in 1944 in Kenya, the second oldest child of Louis and Mary Leakey. As a child he spent a of time in the sunbaked hills of western Kenya sitting around while his parents looked for fossils. He told Smithsonian magazine, “I’m afraid I was a whiney child.” After one “I’m tired. I’m bored” lament, his exasperated father told him, “Go ahead and find your own bone.” He did just that and came up with a large jawbone of an extinct pig.

Richard never went to college. He took up fossil searching after becoming disenchanted with the safari business. He told Smithsonian, “I’d spent most of my life groveling in the sediments so I had a fairly good idea of how to go about these things.”

Richard was very competitive, opinionated and pontificating. He clearly took more after his father than his mother. He feuded with his father and other scientists. Contrary to most other scientist, he still stands by his belief that Australopithecines are not ancestors of humans. He once said, "Man is not innately anything and is capable of everything. Human beings are cultural animals and each one is the product of a particular culture.

Leakey survived a kidney transplant (with a kidney donated by his estranged brother Philip) and lost both of his legs below the knee in a plane crash in Kenya in 1993. He continued to look for fossils periodically with artificial legs. “I had two legs in the grave but I wasn’t dead,” he told Smithsonian.

Richard Leakey's Discoveries and Work

Richard Leakey found further evidence of “Homo habilis” with Alan Walker in 1984 and discovered "Turkana Boy," the most complete skeletal remains of a “ Homo erectus” . In 1972, he found a 1.8-million-old skull at Koobi Fora. See Homo habilis, Homo erectus and Turkana Boy.

Leakey has narrated popular television series, written bestselling books, and is in demand as lecturer. He runs an environmental consulting firm and founded a new political party and headed the opposition movement against Kenya's president Daniel arap Moi in 1995 after becoming appalled by the corruption that existed in his regime. Several of his political supporters were assaulted, beaten and whipped by thugs, presumably by supporters of Moi. A member of the Kenyan parliament Leakey was involved in rewriting Kenya’s constitution and helping the disabled.

Leakey was director of Kenya's Wildlife Service from 1989 to 1994. He was been credited with virtually eradicating poaching in the country's game parks that caused the number of elephants to drop from 100,000 to 19,000 animals in 15 years. He was responsible for the much publicized burning of $5 million worth of ivory. Some have suggested that people in the ivory and elephant poaching business were behind his plane crash.

Leakey raised millions of dollars and directed conservation effort in the fight against poachers. He passed an edict to shoot poachers on site. He resigned in 1994 amid allegations of corruption, racism and mismanagement. He was reinstated 4½ years later by Moi. A year later he resigned from the agency after being pressured, diplomats say, by "powerful ministers" intent on "getting their hands on the money flowing into the agency." Leakey also headed the Kenya National Museum.

Meave Leakey

Turkana boy Meave Leakey, the wife of Richard Leakey and daughter in law of Louis and Mary Leakey, handles most of fossil collecting duties and carries the torch of the Leakey family today along with her eldest daughter Louise.

Meave Leakey was trained as a zoologist. As a child she liked doing jigsaw puzzles with the pieces turned upside down. While working on her doctorate degree in 1965, Meave met Richard after answering a newspaper advertisement for a job at a primate center in Kenya. She later joined Richard doing field work at Lake Turkana. Like his father, Richard Leakey left to his first wife and son — to marry Meave in 1969.

Meave and Richard worked together at Lake Turkana. Naturally shy, Meave remained in the background and did a lot of the fossil hunting and detail work like her mother-in-law Mary, while her husband Richard got most of the credit. She told National Geographic , “Richard was the person in the limelight. I liked it that way. The fame is a bit of a nuisance. But it’s important the team knows the world is looking on.” For years Meave studied fossil monkeys, leaving the more glamorous hominins to her husband Richard. She took over her husband's work in 1989. Today she is very involved in analyzing the environment of early hominins to determine how their habitat influenced their development.

Meave Leakey's Discoveries

In 1995, a team lead by Meave Leakey discovered the fossils of 4.1 million-year-old Australopithecus anamnesis, which at the time of the discovery was the oldest known hominin to clearly walk upright like modern humans. In 1996, her team discovered a 4.1 million-year-old hominin jawbone and 3.5 million-year-old hominin arm bone around Lake Turkana. In 1999, found 3.5-million-year-old “ Kenyanthropus Platyops” also in the Lake Turkana area.

Meave Leakey attributes Leakey's luck to perseverance. She says that her own success has been the result of "having a good site and an excellent team." Frank Brown, a geologist on her team said, “she goes back and goes back and goes back...I asked her why she kept look in the same place, and she said, “Fossil hominids have been collected here, and I can’t believe all of them have been found.”

Meave and Richard's daughter Louise is regarded as the heir to the Leakey legacy. She got a Ph.D. in paleontology from the University of London. At last report she was looking for hominins in northern Kenya and has coauthored papers with her mother. When she was 12 she drove the family Land Rover to fetch water for the fossil hunting teams. Her younger sister Sumira decided to opt out of the family business. She works for the World Bank.

Hominid Gang

The Hominid Gang is name of the mostly Kenyan team of fossil hunters that has worked with the Leakeys over the years and is now associated most with Meave Leakey. The Hominid Gang has traditionally celebrated major discoveries with bottles of beer and goat meat.

Working under various members of the Leakey family, Kamoya Kimeu has been head of the Hominid Gang for several decades. Credited with finding the first bone fragment that lead to the discovery of "Turkana Boy," Kimeu says that he believes the bones he finds speak to him. Mary Leakey once wrote, "No one can find them like Kamoya."

Describing, Kimeu at work, Donatella Lorch wrote in the New York Times, "He paces slowly, head bent, stopping every few meters, and then leans down to pick up what initially looked like a gray piece of stone" but is actually a 4.1 million year bone.

"Many people don't like this kind of work because its hard to understand," Kimeu told the New York Times. "It is very hard work. It is very hot, walking and sitting with animals like mosquitos, snakes, lions. I like looking. I want to find a skull in this area."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018