WHAT MAKES HUMANS HUMAN

What makes humans human? This question has preoccupied scientists and scholars for centuries. Alice Clement wrote in The Conversation,, Today it seems relatively straightforward to tell who is a human and who is not, but looking through the fossil record, things very quickly become less clear. Does humanity begin with the origins of our own species, Homo sapiens, from 300,000 years ago? Or should we stretch things back more than three million years to ancestors such as “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis) from eastern Africa? Or even further back to our split from the other great apes? Or even back further than that. [Source: Alice Clement, Research Associate in the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, The Conversation, January 22, 2023]

In biology, the term “homology” relates to the similarity of a structure based on descent from a shared common ancestor. Think of the similarities of a human hand, a bat wing and a whale flipper. These all have specialist functions, but the underlying body plan of the bones remains the same. This differs from “analogous” structures, such as wings in insects and birds. Although they serve a similar function, the wings of a dragonfly and the wings of a parrot have arisen independently, and don’t share the same evolutionary origin.

Chris Stringer wrote in The Guardian:. Linnaeus, that great classifier of living things, gave us our biological name Homo sapiens (meaning "wise man") and our high rounded skulls certainly make us distinctive, as do our small brow ridges and chins. However, we are also remarkable for our language, art and complex technology. [Source: Chris Stringer, The Guardian, June 19, 2011. Stringer is head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London]

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

What Separates Humans from Animals

Melissa Hogenboom wrote for the BBC: “We once viewed ourselves as the only creatures with emotions, morality, and culture. But the more we investigate the animal kingdom, the more we discover that is simply not true. Many scientists are now convinced that all these traits, once considered the hallmarks of humanity, are also found in animals. If they are right, our species is not as unique as we like to think. [Source: Melissa Hogenboom, BBC, July 3, 2015 |::|]

“Of course not everyone agrees. A species, by definition, is unique. In that trivial sense humans are unique, just as house mice are unique. But when we say humans are unique, we mean something more than that. Throughout history humans have created a seemingly impenetrable barrier between us and other animals. As the philosopher Rene Descartes wrote in the late 1600s: "animals are mere machines but man stands alone". |::|

“Charles Darwin was one of the first to speak out against this idea. In The Descent of Man, he wrote: "There is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties" and that all the differences are "of degree, not of kind". He later extensively documented the similarities between human facial expressions and those of animals. "If a young chimpanzee be tickled," he noted, "as is the case of our young children a more decided chuckling or laughing sound is uttered". He also observed that chimpanzees' eyes wrinkle, sparkle and grow brighter when they laugh.” |::|

“His thoughts were later forgotten or ignored. By the 1950s animals had been reduced to unemotional machines with mere instincts. The behaviourist BF Skinner thought all animals were much the same. "Pigeon, rat monkey, which is which, it doesn't matter." He said that the same rules of learning would apply to them all. At the time, there was a prevailing attitude that they lacked intelligence. There was a taboo against attributing emotions to animals, says Frans de Waal of Emory University in Atlanta, US.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Animal Connection” by Pat Shipman (W.W. Norton, 2011) Amazon.com

“The Link: Uncovering Our Earliest Ancestor” by Colin Tudge with Josh Young Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Fossil Men: The Quest for the Oldest Skeleton and the Origins of Humankind” By Kermit Pattison (2021) Amazon.com

“The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the Past” by Meave Leakey with Samira Leakey (2020) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Masters of the Planet, The Search for Our Human Origins” by Ian Tattersall (Pargrave Macmillan, 2012) Amazon.com;

What Makes Humans Unique from Other Animals

Melissa Hogenboom wrote for the BBC: “In recent years, many traits once believed to be uniquely human, from morality to culture, have been found in the animal kingdom. So, what exactly makes us special? The list might be smaller than it once was, but there are some traits of ours that no other creature on Earth can match. Ever since we learned to write, we have documented how special we are. The philosopher Aristotle marked out our differences over 2,000 years ago. We are "rational animals" pursuing knowledge for its own sake. We live by art and reasoning, he wrote. Much of what he said stills stands. [Source: Melissa Hogenboom, BBC, July 6, 2015 |::|]

“Yes, we see the roots of many behaviours once considered uniquely human in our closest relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos. But we are the only ones who peer into their world and write books about it."Obviously we have similarities. We have similarities with everything else in nature; it would be astonishing if we didn't. But we've got to look at the differences," says Ian Tattersall, a paleoanthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, US. |::|

“Humans and chimpanzees diverged from our common ancestor more than six million years ago. Fossil evidence points to the ways which we have gradually changed. We left the trees, started walking and began to live in larger groups. And then our brains got bigger. Physically we are another primate, but our bigger brains are unusual. We don't know exactly what led to our brains becoming the size they are today, but we seem to owe our complex reasoning abilities to it. |::|

“Evidence in the form of stone tools suggests that for about 100,000 years our technology was very similar to the Neanderthals. But 80,000 years ago something changed. "The Neanderthals had an impressive but basically routine material record for a hominin. Once H. sapiens started behaving in a strange, [more sophisticated] way, all hell broke loose and change became the norm," Tattersall says. We started to produce superior cultural and technological artefacts. Our stone tools became more intricate. |::|

“That our rapidly expanding technology has allowed us all to become instant publishers means we can share such information at the touch of a button. And this transmission of ideas and technology helps us in our quest to uncover even more about ourselves. That is, we use language to continue ideas that others put forward. Of course, we pass on the good and the bad. The technology that defines us can also destroy worlds. Take murder. Humans aren't the only species that kill each other. We're not even the only species that fight wars. But our intelligence and social prowess mean we can do so on an unprecedented scale.” |::|

Art and Abstraction Set Humans Apart from Animals?

Melissa Hogenboom wrote for the BBC: “One study proposes that our technological innovation was key for our migration out of Africa. We started to assign symbolic values to objects such as geometrical designs on plaques and cave art. There is little evidence that any other hominins made any kind of art. One example, which was possibly made by Neanderthals, was hailed as proof they had similar levels of abstract thought. However, it is a simple etching and some question whether Neanderthals made it at all. The symbols made by H. sapiens are clearly more advanced. We had also been around for 100,000 years before symbolic objects appeared so what happened? [Source: Melissa Hogenboom, BBC, July 6, 2015 |::|]

“Somehow, our language-learning abilities were gradually "switched on", Tattersall argues. In the same way that early birds developed feathers before they could fly, we had the mental tools for complex language before we developed it. We started with language-like symbols as a way to represent the world around us, he says. For example, before you say a word, your brain first has to have a symbolic representation of what it means. These mental symbols eventually led to language in all its complexity and the ability to process information is the main reason we are the only hominin still alive, Tattersall argues. It's not clear exactly when speech evolved, or how. But it seems likely that it was partly driven by another uniquely human trait: our superior social skills. |::|

“We are unique in the level of abstractness with which we can reason about others' mental states This tells us something profound about ourselves. While we are not the only creatures who understand that others have intentions and goals, "we are certainly unique in the level of abstractness with which we can reason about others' mental states", says Katja Karg, also of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. |::|

“When you pull together our unparalleled language skills, our ability to infer others' mental states and our instinct for cooperation, you have something unprecedented. Us.Just look around you, Tomasello says, "we're chatting and doing an interview, they (chimps) are not." We have our advanced language skills to thank for that. We may see evidence of basic linguistic abilities in chimpanzees, but we are the only ones writing things down. |::|

“We tell stories, we dream, we imagine things about ourselves and others and we spend a great deal of time thinking about the future and analysing the past.There's more to it, Thomas Suddendorf, an evolutionary psychologist at the University of Queensland in Australia is keen to point out. We have a fundamental urge to link our minds together. "This allows us to take advantage of others' experiences, reflections and imaginings to prudently guide our own behaviour. "We link our scenario-building minds into larger networks of knowledge." This in turn helps us to accumulate information through many generations.” |::|

Mind Reading Sets Humans Apart from Animals?

Melissa Hogenboom wrote for the BBC: “The fact that our nearest relatives share too simply shows that it is an ancient trait. It was already present in the messy branch of early humans that led to us, but none of these other species were as hyper cooperative as we are today. These cooperative skills are closely tied to our incredible mind reading skills. We understand what others think based upon our knowledge of the world, but we also understand what others cannot know. The Sally-Anne task is a simple way to test young children's ability to do this. [Source: Melissa Hogenboom, BBC, July 6, 2015 |::|]

“The child witnesses a doll called Sally putting a marble in a basket in full view of another doll, Anne. When Sally leaves the room, Anne moves the marble to a box. Sally then comes back, and the experimenter asks the child where Sally will look for the marble. Because Sally didn't see Anne move the marble, she will have a "false belief" that the marble is still in the basket. Most 4-year-olds can grasp this, and say that Sally will look in the basket. They know the marble is not there, but they also understand that Sally is missing the key bit of information. |::|

“Chimps can knowingly deceive others, so they understand the world view of others to some extent. However, they cannot understand others' false beliefs. In a chimpanzee version of the Sally-Anne task, researchers found that they understand when a competitor is ignorant of the location of food, but not when they have been misinformed. Tomasello puts it like this: chimpanzees know what others know and what others can see, but not what others believe.” |::|

Important Early Steps in the Evolution Towards Humans

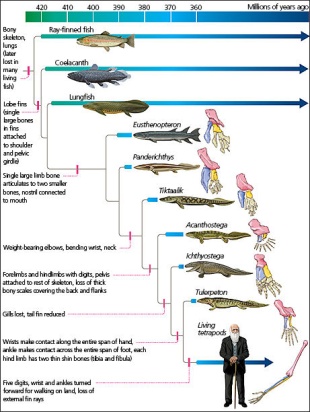

Tetrapods (four-limbed animals with a backbone that eventually moved out of water and onto land) that lived 350 million years ago belong to the ancestral group that led to the human lineage. One tetrapod,,Tristichopterids, found in the fossil record, disappeared in a mass extinction event at the end of the Devonian, Period about 359 million years ago. They have no direct descendants today, but researchers think that a common ancestor with our ancestral lineage existed earlier in the Devonian.

Going back even further to the first animals with backbones, Alice Clement wrote in The Conversation,, To “grow a spine” means to become emboldened and confident. The first animals to do just that must have surely been courageous to venture out into the perilous ancient seas 500 million years ago. First, these worm-like animals evolved a “notochord” – a rod built of cartilage running along the back of the body. This enabled the attachment of segmented muscle blocks and a long tail extending beyond the anus. All animals with a notochord are called chordates, and includes everything from sea squirts to sea gulls, comprising more than 65,000 living species. [Source: Alice Clement, Research Associate in the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, The Conversation, January 22, 2023]

To get an idea of the first chordates, today we can look to animals such as the lancelet (known as Amphioxus or Branchiostoma). Lancelets look a bit like tiny, primitive fishes without fins. They swim by undulating their body from side to side. Next come those with well organised heads (craniates), and those in which the notochord is replaced by a backbone in adults (vertebrates). A backbone is built of individual segmented bones (vertebrae) which fit together in a specific interlocking pattern. We have a few tantalising fossils representing the earliest known examples of vertebrates, such as Metaspriggina known from Canada, or Haikouichthys from China in rocks more than 500 million years old.

The next important step was the development of teeth. In 2022 a team of palaeontologists described isolated fossil fish teeth from Silurian age rocks in Guizhou province, China. This remarkable discovery pushed the minimum age of teeth back a further 14 million years from previous findings. This means our dentition now harks back to a whopping 439 million years ago. That new fish, a very early jawed vertebrate, was named Qianodus duplicis and is only known from isolated specialised teeth known as “whorls”. A tooth whorl is a bizarre row of teeth that curls in on itself in a spiral pattern (most famously present in the buzz-saw shark, Helicoprion). Nevertheless, the teeth in the Chinese jawed fish have a number of features found in other modern jawed vertebrates, which highlight their relevance in understanding the evolution of our very own gnashers. Chomp on that!

Development of Key Human Skeletal Features

Many animals — including humans and advanced mammals — have 10 fingers and 10 toes or close equivalents.Alice Clement wrote in The Conversation, This pattern of five digits, known as a “pentadactyl limb”, is found in most amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. But fish don’t have fingers and toes, so when was it that digits first evolved? A recent study — using powerful imaging methods to peer inside a 380-million-year-old fossil called Elpistostege from Quebec, Canada — described the first digits found preserved within a fish fin, revealing the oldest fish fingers! Somewhat surprisingly, the first fish to evolve digits still retained fin rays around them so these bones would not have been visible on the animal externally. [Source: Alice Clement, Research Associate in the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, The Conversation, January 22, 2023]

The earliest tetrapods (four-limbed animals with a backbone that eventually moved out of water and onto land) “experimented” with the number of digits, sometimes being found with six, seven or eight of them. These earliest tetrapods were likely still living in the water. It wasn’t until tetrapods became truly terrestrial that the five-digit limb arrived. This arrangement most likely arose as a practical solution to weight bearing on land.

Moving on to the skull: In addition to your eyeballs sitting in their orbits, you may be surprised to learn that you have other large holes (known as fenestrae) in your skull. A single window is found on each side of the human skull, uniting us with our shared common ancestors from over 300 million years ago. Animals with this single window in their skulls are known as synapsids. The word means “fused arch”, referring to the bony arch found underneath the opening in the skull behind each eye. Today all mammals, including humans, are synapsids (but reptiles and birds are not).

Importance of Bipedalsim In the Development of Humans

Bipedalism (moving on two legs) is one of the key characteristics that defines hominins and humans. A hominin after all is defined as a creature that stands upright and walks and runs primarily on two legs. It is thought that bipedalism developed in hominins between 4 million and 8 million years ago. No one is sure how or why some apes, who were for the most part arboreal at that time, dropped out of the trees and began walking upright. A popular theory is that it first evolved to free the hands to carry food. Of more than 250 species of primates, only one — humans — walks around on two legs.

Alice Clement wrote in The Conversation, Whatever line you draw in the sand to pinpoint the birth of humanity, one thing is certain. The act of habitually walking around on two legs, known as “bipedalism”, was one of our ancestors’ greatest steps. It’s hard to overestimate the importance of bipedalism in human evolution. Almost every part of our skeleton was affected by the switch from walking on all fours to standing upright. These adaptations include the alignment and size of the foot bones, hip bones, knees, legs, and vertebral column. [Source: Alice Clement, Research Associate in the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, The Conversation, January 22, 2023]

Importantly, we know from fossil skulls that rapid increases in our brain size occurred shortly after we started walking upright. This required changes to the pelvis to allow for our larger-brained babies to fit through a widened birth canal. Our broadened pelvis (sometimes called iliac flaring) is a homologous feature shared with several lineages of early fossil humans, as well as all those living today. Those big brains of ours then fuelled an explosion of art, culture and language, important concepts when considering what makes us human.

See Separate Articles: HOMININ BIPEDALISM: COSTS, BENEFITS. WALKING AND RUNNING factsanddetails.com ; THEORIES ABOUT HOMININ BIPEDALISM; CLIMATE, TREES, LANDSCAPE factsanddetails.com

Humans Evolved Because of Their Interaction with Other Animals?

Pat Shipman, a biological anthropologist at Penn State University, argues that humans evolved the way they have because of their interactions with other animal species. Kat McGowan wrote in Archaeology magazine: In her book “The Animal Connection”, Shipman builds an interesting but somewhat shaky case that our relationships with animals — eating them, working with them, and caring for them — motivated the evolutionary and cultural shifts that made humans what we are today. [Source:Kat McGowan, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2011]

By eating the flesh of animals, an unusual strategy for a primate, our ancestors were able to evolve massive, energy-hungry brains. Hunting big game encouraged our predecessors to disperse across the globe in search of prey, and honed cognitive skills such as memory and attention. "Our ancestors came under selective pressure to pay more attention to other animals and gather more information about them," Shipman writes. The first toolmaking was also part of the animal connection. Early tools were primarily used to butcher and process meat, she points out. Next, language enabled us to share information about animal habits. Early art — a proxy for linguistic and symbolic capabilities — is almost entirely devoted to depictions of creatures, further evidence of animals' significance in the human mind.

“The Animal Connection is an absorbing read. Shipman is a good storyteller, capturing how relationships between humans and animals can transform both species — even in the simple act of teaching a dog to sit. "In that glorious instant when a human and an animal converse respectfully ... something magical happens," she writes. Shipman provides thorough, readable accounts of current archaeological scholarship on animals and early human tool use, language, and art, and debates about domestication, with interesting digressions such as recent findings that dogs may have first been tamed more than 32,000 years ago. By the end of the book, however, her provocative thesis is not argued clearly enough to be satisfying. Ultimately, her account of who we are and how we got this way still feels speculative, a compelling idea in need of convincing proof.

Humans Outlive Apes Because of Genetic Change?

Genetic modifications that appear to allow humans to live longer than other primates may have its origin in a more carnivorous diet because, some scholars argue, these changes may also promote brain development and make us less vulnerable to dementia, aging and diseases such as cancer and heart disease. Charles Q Choi wrote in Livescience: “Chimpanzees and great apes are genetically similar to humans, yet they rarely live for more than 50 years. Although the average human lifespan has doubled in the last 200 years – due largely to decreased infant mortality related to advances in diet, environment and medicine – even without these improvements, people living in high mortality hunter-forager lifestyles still have twice the life expectancy at birth as wild chimpanzees do. [Source: Charles Q Choi, Livescience.com, December 2009 \=/]

Haeckel's Paleontological Tree of Vertebrates (1879); The evolutionary history of species has been described as a "tree" with many branches arising from a single trunk; While Haeckel's tree is outdated, it clearly illustrates the idea

“These key differences in lifespan may be due to genes that humans evolved to adjust better to meat-rich diets, biologist Caleb Finch at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles suggested. The oldest known stone tools manufactured by the ancestors of modern humans, which date back some 2.6 million years, apparently helped butcher animal bones. As our forerunners evolved, they became better at capturing and digesting meat, a valuable, high-energy food, by increasing brain and body size and reducing gut size.” Finch his findings in the December 2009 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. \=/

“Over time, eating red meat, particularly raw flesh infected with parasites in the era before cooking, stimulates chronic inflammation, Finch explained. In response, humans apparently evolved unique variants in a cholesterol-transporting gene, apolipoprotein E, which regulates chronic inflammation as well as many aspects of aging in the brain and arteries. \=/

“One variant found in all modern human populations, known as ApoE3, emerged roughly 250,000 years ago, “just before the final stage of evolution of Homo sapiens in Africa,” Finch explained. ApoE3 lowers the risk of most aging diseases, specifically heart disease and Alzheimer’s, and is linked with an increased lifespan. “I suggest that it arose to lower the risk of degenerative disease from the high-fat meat diet they consumed,” Finch told LiveScience. “Another benefit is that it promoted brain development.” \=/

“Curiously, another more ancient variant of apolipoprotein E found in a lesser degree in all human populations is ApoE4, which is linked with high cholesterol, shortened lifespan and degeneration of the arteries and brain. “The puzzle is, if ApoE4 is so bad, why is it still present?” Finch asked. “It might have some protective effects under some circumstances. A little bit of data suggests that with hepatitis C, you have less liver damage if you have ApoE4.”“ /=\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Pinterest, Pediaa.com

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024