BELLY DANCING

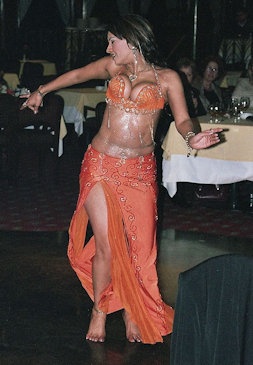

Randa Kamel, Egyptian bellydancer in 2007

Belly dancing is an ancient art and has been a fixture of weddings and parties in the Middle East for centuries. Emphasizing the hips and abdomen, it is known for its belly undulations, shaking buttocks and breasts and intricate hip movements. The best belly dancers can ripple their stomachs and swivel and gyrate their hips in a most alluring manner.

One belly dancer told the New York Times: “It’s joyful but also introspective. It’s soft and feminine and sensual.” Another said it is about “the celebration of women’s bodies and sensuality...It’s important for me to show the dance as a very magical, powerful art form. Not just something to create an atmosphere.” A former modern dancer said, “It’s the best dance I have ever done. It’s creative, playful and very feminine.”

In Turkey and Egypt and other places in the Middle East belly dancer have traditionally been hired for wedding parties. In Egypt it is customary for the bride and groom to have their picture taken with their hands on the belly dancer’s stomach. Belly dancers often have go to lengths to dispel popular misconceptions about their craft, according to the New York Times, yes belly dancers are “feminine, sensual, even sultry...but they were not strippers.

Cairo is considered belly dancing capital of the Middle East. Belly dancers are fixtures of weddings, Pyramid road nightclubs and dinner cruises. The women are so good at what they do that Saudis have been observed putting thousands of dollars in a dancer's garters. A 1920 law forbids the showing of the naval. The laws is skirted by using a naval jewel or lace stomach. The government Artist Inspection Department employs about two dozen agents to check-out nightclubs and discos to make sure the belly dancing shows don't feature dancing or gyrations considered too suggestive.

Most big Turkish celebrations are not complete without a belly dancer. Custom dictates that a when belly dancer comes and dances on a table, the men sitting around it are supposed to place money in her bikini top and g-string. The school in Istanbul I worked at had a reputation for being very cheap. The belly dancer at one of our parties performed for about five minutes and stormed off in a huff when people only gave her 1000 lira banknotes (worth about 25¢ at that time) instead of 10,000 and 20,000 lira bills.

Websites and Resources: Arabs: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Who Is an Arab? africa.upenn.edu ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Arab Cultural Awareness fas.org/irp/agency/army ; Arab Cultural Center arabculturalcenter.org ; 'Face' Among the Arabs, CIA cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence ; Arab American Institute aaiusa.org/arts-and-culture ; Introduction to the Arabic Language al-bab.com/arabic-language ; Wikipedia article on the Arabic language Wikipedia

History of Belly Dancing

Described by some as the oldest dance in the world, belly dancing is said to date back at least to the time of Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.). Some say its roots lie in fertility rituals of ancient Egypt and Greece. Others say it was brought from India to the Middle East by Roma (Gypsies) who also developed flamenco from it in Morocco and Spain. Examples of dances similar to belly dancing can be seen in ancient Egyptian tomb paintings.

Belly dancing was originally done by women for women The undulating belly is said to resemble a woman giving birth. The dancing helped women strengthened the their stomach muscles and served as a form or self-hypnosis.

The transformation of belly dancing to what it is today can be traced back to a performance by a Syrian woman named Little Egypt at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Audiences were shocked and entrepreneurs began making a fortune by hiring out strippers that did their interpretation of the Little Egypt dance as they popped out of cakes.

There is a long tradition of male belly dance teachers but few male belly dancers. One Istanbul club featured a belly dance show. In Cairo, a man who underwent a sex change operation performed for a while before the outcry drove him from the stage.

Belly Dancers as Performers

Belly dancers usually dance to Turkish or Middle Eastern music played on a tape player performed by a band with a drum, clarinet-like instrument, lap harp and Turkish mandolins. Sometimes they sing popular or classical songs with a raunchy edge and drape themselves in veils. Other times they balance candelabras and swords on their heads and invite members of the audience to join them on stage.

Professional belly dancers regard themselves as artists. They bristle at the thought that are little more than stylized strippers. They receive large sums of money for performing at nightclubs and private parties and weddings. Low level dancers work hard to please the crowds and earn money from tips.

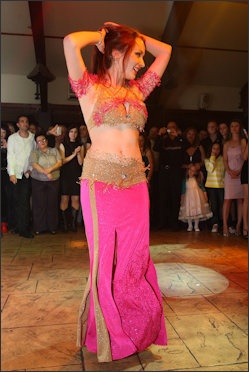

Katya Malaya

Describing a belly dancer at a show in New York, Shayna Samuels wrote in the New York Times: “Jehan stepped onto Taja’s small, rose-petal-covered stage carrying a lotus flower in each hand. With her legs held together like a mermaid, she framed her face with diamond-shaped arms and smiled lasciviously at the crowd. Wearing a sheer burgundy veil with jewels rattling from her chest and hips, she turned away from the audience and dropped suddenly to her back, drawing attention to her stomach with dramatic, isolated pulses.”

Reviewing a performance by the Serena Dance Theater troupe at Lincoln Center Out of Doors in 2001, the Village Voice wrote: “Her dancers, working those rhumba, chiftetelli, and kashlimar rhythms, showed classic Serena training – elegant carriage, willowy arms and hips that make tiny flicks like a clock’s second hand. Highlights included Sahar’s gold wings rippling a la Loie Fuller, a duo undulating with swords balanced on wrists or hips, and a third dancer toting a plate of blazing candles on her sliding head.”

Describing a belly dancer at a wedding, one writer wrote: she "cavorts with the master of ceremonies, lifting her dress, pushing out her leg, lying on the floor and gyrating, rubbing up against him, playing, controlling the arena. Guests slip banknotes into the dancer's waistband or bra or wave money in the air, that is snatched by the dancer, for an opportunity to share the stage with the dancer, dancing or being made fun of.”

Famous Belly Dancers

Most belly dancers use only one name. They are generally expected to have large breasts and a healthy size bottom. A little plump is better than too thin. Traditional belly-dancing costumes consist of a glittering, sequined halter top and long, gauzy skirt. Sometimes the belly is covered and highlighted with fringe or a a wide embroidered panel. Some dancers have 5,000 costumes that come in a variety of color, sequin ranges and locations of slits and cuts.

The Egyptian Takia Karyoka is regarded by many as the best belly dancer of all time. She enchanted Nazis, Allies and Arabs during and after World War II. Samia Gamal is considered the Middle East’s greatest belly dancer in the 1950s and 60s. She was also an actress. Egyptian films from the 1940s and 50s often had a belly dancer at the center of their story.

In Egypt, the romances, tiffs, scandals, wealth and salaries of celebrity belly dancers provides juicy material for gossip columns. Top dancers in the 1990s included Lucy, Fifi Abdou and Dina. Lucy owned about 600 costumes while Fifi Abdou owned about 5,000. Israeli-Egyptian ties were slightly damaged by allegations that the Egyptian ambassador to Israel sexually assaulted an Israeli belly dancer. This charges appeared around the same that an Israeli spy was passing messages on women’s underwear.

Naima Akef, bellydancer and actress

For many years Amor y Libertad nightclub in north Beirut featured performances by Mousabah Ballbaki, the Middle East’s best known and perhaps only regularly-performing male belly dancer. Describing his show, Susan Sachs wrote in the New York Times. “Its not a transvestite show or a striptease. It is more like ‘Saturday Night fever’ meets ‘The Thousand and One Nights.” Sinuous and seductive, dressed in...a gauzy black caftan over a Bedouin-style white robe, he undulates on stage with a faraway look in his eyes and a bodyguard close at hand.” At that time Balbaki had a day job as a fashion editor at a glossy Lebanese magazine. Many people resented what he was doing. People in the audience squirmed in their seats. Some taunted and heckled him. A few throw things at him.

In the mid-1990s, everyone in Cairo was talking about he belly dancer Diana and her decision to forsake the traditional sequined costume for biking shorts an a bikini top, with gold chains rapped around her waist. The controversial designer of Diana's belly dancing outfits, Ahamd Diaa Eddin, runs a shop in Cairo, has his own website and publishs a quarterly magazine.

Japanese Kasumi Kimura is the only Asian professional belly dancer in Cairo. She taught yoga and dance after finishing junior college and was inspired to take up belly dancing after seeing it in a movie. “I knew this was the dancing I had been searching for," she told the Yomiuri Shimbun. After studying under famous choreographers in Turkey and Egypt she made her debut in 1987 and was still performing in 2009.

Belly Dancing, Islamists, and the West

Belly dancing is very popular in the West. Most American cities have belly dancing schools and community centers that offer belly dancing classes. It is also a fixture of some Middle Eastern restaurants and dinner clubs.

Dancers often learn the “cabaret style” which is heavily influenced by the image of belly dancing depicted in Hollywood films. In the early 2000s, professional dancers earned about $125 for a 20 minute performance plus tips. They refuse to perform at bachelor parties out of concern of being confused for something they are not. Some earn as a much as a $12,000 in tips performing before bigshots in Europe, the Middle East and the Caribbean and by doing shows on luxury cruises and in Las Vegas.

Pressure by Islamists have caused the shows to tone down their erotic aspects and require dancers to cover their belies. In some cases belly dancing shows are banned outright.

Flaubert on Dancer-Prostitutes

Describing “almehs” (a word for dancing girls or prostitutes that literally means "learned woman") in Esna, Egypt, the famous French writer Gustace Flaubert wrote in 1850, "Bambej precedes us...She was thin, with a narrow forehead, her eyes painted with antimony, a veil passed over her head and held with her elbows. She was followed by a pet sheep, whose wool was painted in spots with yellow henna. Around its nose was a black velvet muzzle." [Source: “Eyewitness to History”, edited by John Carey, Avon, 1987]

"Kuchuk Hanme is a tall, splendid creature, lighter in coloring than an Arab; she comes from Damascus; her skin, particularly on her body, is slightly coffee-colored. When she bends, her flesh ripples in bronze ripples. her eyes are dark and enormous, her eyebrows black, her nostrils open and wide; heavy shoulders, full, apple-shaped breasts...On her right arm is tattooed a line of blurred writing."

“She asks if we would like a little entertainment, but Max says that he would like to entertain himself alone with her, and they go downstairs. After he finished, I go down and follow his example. Ground-floor room, with a divan and a “cafas” [an upturned palm-fibre basket] with a mattress...The best was the second copulation with Kuckuk. Effect of her necklace between my teeth, her cunt felt like rolls of velvet as she made me come. I felt like a tiger."

Dance of the Dancer-Prostitutes

On the dancing, Flaubert wrote: "The musicians arrive: a child and an old man, whose left eye is covered with a rag; they both scrape on the “rebah”, a kind of small round violin with a metal leg that rests on the ground and two horse-hair strings...Kuchuk Hanmen and Bambeh begin to dance."

"Kuckuk's dance is brutal. She squeezes her bare breasts together with her jacket. She puts on a girdle fashioned from a brown shawl with gold stripes, with three tassels hanging on ribbons. She rises first on one foot, then on the other—marvelous movement: when one is on the ground, the other moves up and across in front of the shin-bone—the whole thing was a light bound...Bambeh prefers a dance on a straight line; she moves with lowering and raising of one hip only, a kind of rhythmic limping of great character.

“Kuchuk dances the Bee...Kuchuk shed her clothing as she dances. Finally she was naked except for a “fichu”, which she held in her hands and behind who she pretended to hide, and a at the end she threw down the “fichu” . That was the Bee. She danced very briefly and said she does not like to that dance...she sank down breathless on her dican, her body continuing to move slightly in rhythm. One of women threw her enormous white striped pajamas; she pulled them on up to her neck. The two musicians were unblindfoled.”

Cairo’s Top Costume Maker on Belly Dancing’s Decline

Jeffrey Fleishman wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Ahmed Diaa Eddin sits amid beads and sequins bargaining hard with a woman from Saudi Arabia over satin and chiffon...At 60, there's a hint of nostalgia about him, as if somewhere along the way he slipped out of a Peter Lorre movie and can't quite find his way back. [Source: Jeffrey Fleishman, Los Angeles Times, December 14, 2007 =]

“Egypt's best dancers have worn his costumes, women who can earn up to $3,000 for a single show. He knows the nightclubs, the orchestras, the bartenders, the discreetly sipped drink, the scent of the water pipe, and that feeling when the lights go down and the tables fall quiet as the tabla drum sounds and the silhouette appears, sometimes in high heels, sometimes not. "Tastes change, beauty stays the same," he says. "But, you know, the golden days of belly dancing are gone. It's deteriorating all over Egypt. Most of my costumes are exported. This country has many dancers, but the quality is poor. I blame these music videos. They're harming belly dancing. You get this director who hires five or six girls, dresses them in belly dancer outfits, but they're not professional. They can't dance. But people see them on TV and they get hired in clubs. This is what's wrong." =

“Even Muhammad Ali Street, the fabled strip of belly dancing, is not what it used to be. The artists have slipped away to other neighborhoods, leaving behind upholsterers and tailors, men with swift hands and steady feet working vintage Singer sewing machines. "I began as a costume designer on this street when I was 16, but I've been in and out of nightclubs since I was 9," Diaa Eddin says. "I was a loser at school. But if I hadn't been a loser back then I wouldn't be famous today. . . . Sometimes a woman will come to me today. She wants an outfit, but she doesn't have big breasts, so I have to do a bit of cosmetic surgery on the costume to make her look bigger." =

“Women come and go, flicking through catalogs, scrutinizing folds of satin and Lycra, shaking bead boxes. Some of them are shopping for bridal gifts while others, like the Saudi woman, who wore a hijab and covered all but her eyes, want to entice husbands in the privacy of their homes. Some belly dance for art, many ripple and shake their hips for exercise, especially in Scandinavia and Germany, which imports more of Diaa Eddin's costumes than any other nation, including the United States, which comes in third. He has lost a number of clients. Renowned dancers Hendeyya and Sahar Hamdi became devout Muslims. They wear hijabs and keep their midriffs covered, part of an Islamic revival here in recent years. "I think there were motives other than religion," he says. "Some of the dancers and actresses taking up the veil now just want to get married." =

"Belly dancing is a legacy from the time of the pharaohs," he says. "Ancient Egyptians believed the belly dancer had an easier time in labor during childbirth. The costume is a sign of joy. It shows the allure of a woman's body. Egyptian women are inherently good at belly dancing. I don't know why, they just are. Today, though, it's the foreigners who like the traditional costumes and the Egyptians prefer the more revealing, tighter-fitting style." =

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018