ST. AUGUSTINE

St. Augustine St. Augustine (A.D. 354-430) has been called the most influential Christian “between Saint Paul and Luther.” Born under the name Aurelius Augustinus, he was the Christian bishop of Hippo, a North African Roman outpost in the waning days of the Roman Empire, when Christian communities were well established but divided.

St. Augustine’s efforts helped clarify many divisive doctrinal issues and helped define what the Christian church is today. His account of his early life in his “Confessions” is widely regarded as classic biography of the conversion experience. In addition to the contributions he made to religion Augustine has also been called the first great psychologist, the father of the autobiography and pioneer of using literature to analyze himself and to explore self consciousness. His philosophy drew heavily on Platonic concepts.

Carl A. Volz wrote: “Augustine combined the creative power of Tertullian and the intellectual breadth of Origen with the ecclesiastical sense of Cyprian, the dialectical acumen of Aristotle with the idealistic enthusiasm and profound speculation of Plato, the practical sense of the Latin with the agile intellect of the Greek. Augustine is the greatest philosopher of the patristic age and arguably the most important and influential theologian of the church after the New Testament. The doctrinal magisterium of the church has probably followed no other theological author so often as it has followed him, certainly in the West.” [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu, 1997]

See Separate Articles: ST. AUGUSTINE'S TEACHINGS, WRITING AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO CHRISTAINITY europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org; Bible: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks; Bible History Online bible-history.com ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Saints and Their Lives Today's Saints on the Calendar catholicsaints.info ; Saints' Books Library saintsbooks.net ; Saints and Their Legends: A Selection of Saints libmma.contentdm ; Saints engravings. Old Masters from the De Verda collection colecciondeverda.blogspot.com ; Lives of the Saints - Orthodox Church in America oca.org/saints/lives ; Lives of the Saints: Catholic.org catholicism.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Augustine of Hippo” by Peter Brown Amazon.com ;

“Confessions” by Saint Augustine and R. S. Pine-Coffin (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“City of God” by Augustine of Hippo and Henry Bettenson (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“Early Christian Doctrines” by J. N. D. Kelly Amazon.com ;

“The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Vol. 1 (100-600) by Jaroslav Pelikan Amazon.com ;

“The Spirit of Early Christian Thought: Seeking the Face of God” by Robert Louis Wilken Amazon.com ;

“Early Christian Fathers” by Cyril Richardson Amazon.com ;

“The Apostolic Fathers: A New Translation” by Rick Brannan Amazon.com ;

“When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers” by Marcellino D'Ambrosio Amazon.com ;

“Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers” by Andrew Louth and Maxwell Staniforth Amazon.com ;

“The New Testament in Its World: An Introduction to the History, Literature, and Theology of the First Christians” by N. T. Wright and Michael F. Bird Amazon.com ;

“Concise Theology: A Guide to Historic Christian Beliefs” by J. I. Packer Amazon.com ;

“Christian Theology” by Millard J. Erickson Amazon.com ;

“Christian Theology: An Introduction” by McGrath Amazon.com ;

“The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire” by Alan Kreider Amazon.com ;

“Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years” by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Walter Dixon, et al. Amazon.com ;

“A History of Christianity” by Paul Johnson, Wanda McCaddon, et al. Amazon.com

Augustine’s Life

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “Augustine is the first ecclesiastical author the whole course of whose development can be clearly traced, as well as the first in whose case we are able to determine the exact period covered by his career, to the very day. He informs us himself that he was born at Thagaste (Tagaste; now Suk Arras), in proconsular Numidia, Nov. 13, 354; he died at Hippo Regius (just south of the modern Bona) Aug. 28, 430. [Both Suk Arras and Bona are in the present Algeria, the first 60 m. W. by s. and the second 65 m. w. of Tunis, the ancient Carthage.] [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu /~/]

Carl A. Volz wrote: Father, Patricius, a municipal official, came to the Church as a catechumen only late in life and was baptized shortly before his death (371). Mother, Monica, was a devout Christian. Augustine went first to Carthage for his education, made a liason with a woman which lasted until about 384. Son, Adeodatus (d. 390) was born in 372. In 373 while reading Cicero's Hortensius he developed a desire for a philosophical foundation for his life. Shortly thereafter he joined the Manicheans as an "auditor". He returned to Thagaster 374-375 and became a professor of Liberal Arts, but Monica refused to let him live with her at home because he had rejected Christianity. After his talk with Faustus of of Milevis, the leading Manichee, he gave up that philosophy as he thought Faustus was a babbler. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu, 1997]

“In 384 he moved to Rome, by this time skeptical of philosophy. In the same year he received an appointment as professor of rhetoric in Milan, and this through the influence of Symmachus in Rome, pagan prefect. Augustine now was attracted to Neo-Platonism and the works of Plotinus. He continued to study this as well as Christianity through the teaching of Simplicianus, a Neo-Platonic Christian who later succeeded Ambrose. In 385 he resigned his position and retired to Cassiciacum, an estate near Milan. He was baptized by Ambrose on Easter Eve in 387, together with his son. Then he set out to return to Africa with his son and Monica, but she died on the trip. By 388 he arrived back in Thagaste, where he lived for three years in monastic seclusion. In 391 he was ordained a priest against his will. In 395 he became Bp. Valerius' of Hippo's co-adjutor bishop, and soon after succeeded him as bishop.

“As a bishop he continued the monastic community life with his clergy from which derives the Augustinian Rule. Now he devoted himself to literary work, especially the struggle against heresies. First he engaged Manicheism, then Donatism, and finally Pelagianism. He died at Hippo on August 28, 430, while the city was being besieged by the Vandals.” /::\

St. Augustine's Early Life and Parents

Augustine at the school of Taghaste St. Augustine was born in Tagaste in Numidia (present-day Souk-Ahras in east Algeria) on November 13, 354. His father was a wealthy Berber landowner and pagan. His mother, the future St. Monica, was a devout Christian. His father's hedonist ways had a strong influence on Augustine in his early life. He forsook his Christian upbringing at age sixteen to attend school in Carthage, where he "dabbled with astrology."

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “ His father Patricius, as a member of the council, belonged to the influential classes of the place; he was, however, in straitened circumstances, and seems to have had nothing remarkable either in mental equipment or in character, but to have been a lively, sensual, hot-tempered person, entirely taken up with his worldly concerns, and unfriendly to Christianity until the close of his life; he became a catechumen shortly before Augustine reached his sixteenth year (369-370).

To his mother Monnica (so the manuscripts write her name, not Monica; b. 331, d. 387) Augustine later believed that he owed what lie became. But though she was evidently an honorable, loving, self-sacrificing, and able woman, she was not always the ideal of a Christian mother that tradition has made her appear. Her religion in earlier life has traces of formality and worldliness about it; her ambition for her son seems at first to have had little moral earnestness and she regretted his Manicheanism more than she did his early sensuality. It seems to have been through Ambrose and Augustine that she attained the mature personal piety with which she left the world.

Of Augustine as a boy his parents were intensely proud. He received his first education at Thagaste, learning, to read and write, as well as the rudiments of Greek and Latin literature, from teachers who followed the old traditional pagan methods. He seems to have had no systematic instruction in the Christian faith at this period, and though enrolled among the catechumens, apparently was near baptism only when an illness and his own boyish desire made it temporarily probable. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu /~/]

St. Augustine's Hedonism

St. Augustine was a womanizer, gambler and critic of the virtues. He fathered a son from a mistress before he turned twenty, lived with her for 10 years out of wedlock, and then dumped her so he could marry a socialite. Even after he entered a monastery he used to pray, "Give me chastity, but not yet!”

young Augustine?

Some scholars believe that St. Augustine was gay. This assertion is based in part on a passage from “Confessions” about a man he knew as youth. "I felt that his soul and mine were 'one soul in two bodies' and therefore life without him was horrible. I hated to live as half of a life." After the man's death Augustine said he contemplated suicide but “I feared to die, lest he should die wholly whom I had loved so greatly." Despite his hedonistic ways, St. Augustine was drawn to religious cults that preached self denial.

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “His father, delighted with his son's progress in his studies, sent him first to the neighboring Madaura, and then to Carthage, some two days' journey away. A year's enforced idleness, while the means for this more expensive schooling were being accumulated, proved a time of moral deterioration; but we must be on our guard against forming our conception of Augustine's vicious living from the Confessiones alone. To speak, as Mommsen does, of " frantic dissipation " is to attach too much weight to his own penitent expressions of self-reproach. Looking back as a bishop, he naturally regarded his whole life up to the " conversion " which led to his baptism as a period of wandering from the right way; but not long after this conversion, he judged differently, and found, from one point of view, the turning point of his career in his taking up philosophy -in his nineteenth year. According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

This view of his early life, which may be traced also in the Confessiones, is probably nearer the truth than the popular conception of a youth sunk in all kinds of immorality. When he began the study of rhetoric at Carthage, it is true that (in company with comrades whose ideas of pleasure were probably much more gross than his) he drank of the cup of sensual pleasure. But his ambition prevented him from allowing his dissipations to interfere with his studies. His son Adeodatus was born in the summer of 372, and it was probably the mother of this child whose charms enthralled him soon after his arrival at Carthage about the end of 370. But he remained faithful to her until about 385, and the grief which he felt at parting from her shows what the relation had been. In the view of the civilization of that period, such a monogamous union was distinguished from a formal marriage only by certain legal restrictions, in addition to the informality of its beginning and the possibility of a voluntary dissolution. Even the Church was slow to condemn such unions absolutely, and Monnica seems to have received the child and his mother publicly at Thagaste. In any case Augustine was known to Carthage not as a roysterer but as a quiet honorable student. He was, however, internally dissatisfied with his life.

St. Augustine wrote in Confessions: Book III: Chapter I: 1. I came to Carthage, where a caldron of unholy loves was seething and bubbling all around me. I was not in love as yet, but I was in love with love; and, from a hidden hunger, I hated myself for not feeling more intensely a sense of hunger. I was looking for something to love, for I was in love with loving, and I hated security and a smooth way, free from snares. Within me I had a dearth of that inner food which is thyself, my God — although that dearth caused me no hunger. And I remained without any appetite for incorruptible food — not because I was already filled with it, but because the emptier I became the more I loathed it. Because of this my soul was unhealthy; and, full of sores, it exuded itself forth, itching to be scratched by scraping on the things of the senses. Yet, had these things no soul, they would certainly not inspire our love. To love and to be loved was sweet to me, and all the more when I gained the enjoyment of the body of the person I loved. Thus I polluted the spring of friendship with the filth of concupiscence and I dimmed its luster with the slime of lust. Yet, foul and unclean as I was, I still craved, in excessive vanity, to be thought elegant and urbane. And I did fall precipitately into the love I was longing for. My God, my mercy, with how much bitterness didst thou, out of thy infinite goodness, flavor that sweetness for me! For I was not only beloved but also I secretly reached the climax of enjoyment; and yet I was joyfully bound with troublesome tics, so that I could be scourged with the burning iron rods of jealousy, suspicion, fear, anger, and strife. [Source: Augustine: Confessions, translated and edited by Albert C. Outler, Ph.D., D.D., Professor of Theology, Southern Methodist University, 1955]

Augustine’s Neoplatonist Period

Manichean Jesus and Adam

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy:The Hortensius of Cicero, now lost with the exception of a few fragments, made a deep impression on him. To know the truth was henceforth his deepest wish. About the time when the contrast between his ideals and his actual life became intolerable, he learned to conceive of Christianity as the one religion which could lead him to the attainment of his ideal. But his pride of intellect held him back from embracing it earnestly; the Scriptures could not bear comparison with Cicero; he sought for wisdom, not for humble submission to authority.” /~/

“In his thirty-first year he was strongly attracted to Neoplatonism by the logic of his development. The idealistic character of this philosophy awoke unbounded enthusiasm, and he was attracted to it also by its exposition of pure intellectual being and of the origin of evil. These doctrines brought him closer to the Church, though he did not yet grasp the full significance of its central doctrine of the personality of Jesus Christ. In his earlier writings he names this acquaintance with the Neoplatonic teaching and its relation to Christianity as the turning-point of his life. The truth, as it may be established by a careful comparison of his earlier and later writings, is that his idealism had been distinctly strengthened by Neoplatonism, which had at the same time revealed his own will, and not a natura altera in him, as the subject of his baser desires. This made the conflict between ideal and actual in his life more unbearable than ever. Yet his sensual desires were still so strong that it seemed impossible for him to break away from them.” /~/

St. Augustine wrote in Confessions: Chapter IV: Among such as these, in that unstable period of my life, I studied the books of eloquence, for it was in eloquence that I was eager to be eminent, though from a reprehensible and vainglorious motive, and a delight in human vanity. In the ordinary course of study I came upon a certain book of Cicero's, whose language almost all admire, though not his heart. This particular book of his contains an exhortation to philosophy and was called Hortensius. Now it was this book which quite definitely changed my whole attitude and turned my prayers toward thee, O Lord, and gave me new hope and new desires. Suddenly every vain hope became worthless to me, and with an incredible warmth of heart I yearned for an immortality of wisdom and began now to arise that I might return to thee. It was not to sharpen my tongue further that I made use of that book. I was now nineteen; my father had been dead two years, and my mother was providing the money for my study of rhetoric. What won me in it [i.e., the Hortensius] was not its style but its substance.

“How ardent was I then, my God, how ardent to fly from earthly things to thee! Nor did I know how thou wast even then dealing with me. For with thee is wisdom. In Greek the love of wisdom is called "philosophy," and it was with this love that that book inflamed me. There are some who seduce through philosophy, under a great, alluring, and honorable name, using it to color and adorn their own errors. And almost all who did this, in Cicero's own time and earlier, are censored and pointed out in his book.

Augustine’s Manichean Period

After teachings rhetoric for several years in Carthage he moved to Rome, where he converted for a time to Manichaeanism, a sect led by a Persian prophet that viewed spirituality as a struggle within the body and promoted avoiding sex, eating only vegetables and believing that the personal fight between good and evil represented a cosmic battle. St. Augustine was also influenced by the Skeptics, a group that in its extreme forms avoided all activity and human contact by going into the desert. One of its central ideas was that it was impossible to be sure about anything.

scene from a Manichean book

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “In this frame of mind he was ready to be affected by the so-called "Manichean propaganda" which was then actively carried on in Africa, without apparently being much hindered by the imperial edict against assemblies of the sect. Two things especially attracted him to the Manicheans: they felt at liberty to criticize the Scriptures, particularly the Old Testament, with perfect freedom; and they held chastity and self-denial in honor. The former fitted in with the impression which the Bible had made on Augustine himself; the latter corresponded closely to his mood at the time. The prayer which he tells us he had in his heart then, " Lord, give me chastity and temperance, but not now," may be taken as the formula which represents the attitude of many of the Manichean auditores. Among these Augustine was classed during his nineteenth year; but he went no further, though he held firmly to Manicheanism for nine years, during which he endeavored to convert all his friends, scorned the sacraments of the Church, and held frequent disputations with catholic believers. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu /~/]

“Having finished his studies, he returned to Thagaste and began to teach grammar, living in the house of Romanianus, a prominent citizen who had been of much service to him since his father's death, and whom he converted to Manicheanism. Monnica deeply grieved at her son's heresy, forbade him her house, until reassured by a vision that promised his restoration. She comforted herself also by the word of a certain bishop (probably of Thagaste) that "the child of so many tears could not be lost." He seems to have spent little more than a year in Thagaste, when the desire for a wider field, together with the death of a dear friend, moved him to return to Carthage as a teacher of rhetoric. /~/

“The next period was a time of diligent study, and produced (about the end of 380) the treatise, long since lost, De pulchro et apto. Meanwhile the hold of Manicheanism on him was loosening. Its feeble cosmology and metaphysics had long since failed to satisfy him, and the astrological superstitions springing from the credulity of its disciples offended his reason. The members of the sect, unwilling to lose him, had great hopes from a meeting with their leader Faustus of Mileve; but when he came to Carthage in the autumn of 382, he too proved disappointing, and Augustine ceased to be at heart a Manichean. He was not yet, however, prepared to put anything in the place of the doctrine he had held, and remained in outward communion with his former associates while he pursued his search for truth. Soon after his Manichean convictions had broken down, he left Carthage for Rome, partly, it would seem, to escape the preponderating influence of his mother on a mind which craved perfect freedom of investigation. Here he was brought more than ever, by obligations of friendship and gratitude, into close association with Manicheans, of whom there were many in Rome, not merely auditores but perfecti or fully initiated members.

See Manicheism EARLY CHRISTIAN AND CHRISTIAN-LIKE SECTS: THOMASINES, ASCETICS AND MANICHEISM factsanddetails.com

St. Augustine Return to Christianity in Milan with St. Ambrose

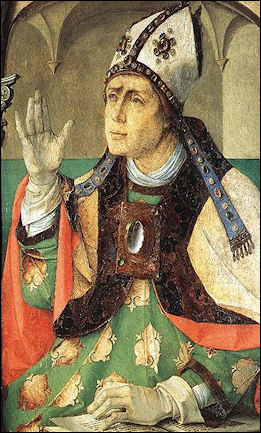

Augustine with the Holy Spirit St. Augustine became interested again in Christianity when he moved to Milan with his mother and came under the influence of the city’s famous bishop, St. Ambrose.

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: he prefect Symmachus sent him to Milan, certainly before the beginning of 385, in answer to a request for a professor of rhetoric. “The change of residence completed Augustine's separation from Manicheanism. He listened to the preaching of Ambrose and by it was made acquainted with the allegorical interpretation of the Scriptures and the weakness of the Manichean Biblical criticism, but he was not yet ready to accept catholic Christianity. His mind was still under the influence of the skeptical philosophy of the later Academy. This was the least satisfactory stage in his mental development, though his external circumstances were increasingly favorable. He had his mother again with him now, and shared a house and garden with her and his devoted friends Alypius and Nebridius, who had followed him to Milan; his assured social position is shown also by the fact that, in deference to his mother's entreaties, he was formally betrothed to a woman of suitable station.

“As a catechumen of the Church, he listened regularly to the sermons of Ambrose. The bishop, though as yet he knew nothing of Augustine's internal struggles, had welcomed him in the friendliest manner both for his own and for Monnica's sake. Yet Augustine was attracted only by Ambrose's eloquence, not by his faith; now he agreed, and now he questioned. Morally his life was perhaps at its lowest point. On his betrothal, he had put away the mother of his son; but neither the grief which he felt at this parting nor regard for his future wife, who was as yet too young for marriage, prevented him from taking a new concubine for the two intervening years. Sensuality, however, began to pall upon him, little as he cared to struggle against it. His idealism was by no means dead; he told Romanian, who came to Milan at this time on business, that he wished he could live altogether in accordance with the dictates of philosophy; and a plan was even made for the foundation of a community retired from the world, which should live entirely for the pursuit of truth. With this project his intention of marriage and his ambition interfered, and Augustine was further off than ever from peace of mind. /~/

St. Augustine wrote in Confessions: Book V: Chapter XIII: 23: And to Milan I came, to Ambrose the bishop, famed through the whole world as one of the best of men, thy devoted servant. His eloquent discourse in those times abundantly provided thy people with the flour of thy wheat, the gladness of thy oil, and the sober intoxication of thy wine. To him I was led by thee without my knowledge, that by him I might be led to thee in full knowledge. That man of God received me as a father would, and welcomed my coming as a good bishop should. And I began to love him, of course, not at the first as a teacher of the truth, for I had entirely despaired of finding that in thy Church — but as a friendly man. And I studiously listened to him — though not with the right motive — as he preached to the people. I was trying to discover whether his eloquence came up to his reputation, and whether it flowed fuller or thinner than others said it did. And thus I hung on his words intently, but, as to his subject matter, I was only a careless and contemptuous listener. I was delighted with the charm of his speech, which was more erudite, though less cheerful and soothing, than Faustus' style. As for subject matter, however, there could be no comparison, for the latter was wandering around in Manichean deceptions, while the former was teaching salvation most soundly. But "salvation is far from the wicked," such as I was then when I stood before him. Yet I was drawing nearer, gradually and unconsciously. [Source: Augustine: Confessions, translated and edited by Albert C. Outler, Ph.D., D.D., Professor of Theology, Southern Methodist University, 1955]

Augustine’s Conversion

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “Help came in a curious way. A countryman of his, Pontitianus, visited him and told him things which he had never heard about the monastic life and the wonderful conquests over self which had been won under its inspiration. Augustine's pride was touched; that the unlearned should take the kingdom of heaven by violence, while he with all his learning was still held captive by the flesh, seemed unworthy of him. When Pontitianus had gone, with a few vehement words to Alypius, he went hastily with him into the garden to fight out this new problem. Then followed the scene so often described. Overcome by his conflicting emotions he left Alypius and threw himself down under a fig-tree in tears. From a neighboring house came a child's voice repeating again and again the simple words Tolle, lege, " Take up and read." It seemed to him a heavenly indication; he picked up the copy of St. Paul's epistles which he had left where he and Alypius had been sitting, and opened at Romans xiii. When he came to the words, " Let us walk honestly as in the day; not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness," it seemed to him that a decisive message had been sent to his own soul, and his resolve was taken. Alypius found a word for himself a few lines further, " Him that is weak in the faith receive ye;" and together they went into the house to bring the good news to Monnica. This was at the end of the summer of 386. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu /~/]

Augustine's Conversion

St. Augustine wrote in Confessions: Book VIII: Chapter XII: 28. Now when deep reflection had drawn up out of the secret depths of my soul all my misery and had heaped it up before the sight of my heart, there arose a mighty storm, accompanied by a mighty rain of tears. That I might give way fully to my tears and lamentations, I stole away from Alypius, for it seemed to me that solitude was more appropriate for the business of weeping. I went far enough away that I could feel that even his presence was no restraint upon me. This was the way I felt at the time, and he realized it. I suppose I had said something before I started up and he noticed that the sound of my voice was choked with weeping. And so he stayed alone, where we had been sitting together, greatly astonished. I flung myself down under a fig tree — how I know not — and gave free course to my tears. The streams of my eyes gushed out an acceptable sacrifice to thee. And, not indeed in these words, but to this effect, I cried to thee: "And thou, O Lord, how long? How long, O Lord? Wilt thou be angry forever? Oh, remember not against us our former iniquities." For I felt that I was still enthralled by them. I sent up these sorrowful cries: "How long, how long? Tomorrow and tomorrow? Why not now? Why not this very hour make an end to my uncleanness?"[Source: Augustine: Confessions, translated and edited by Albert C. Outler, Ph.D., D.D., Professor of Theology, Southern Methodist University, 1955]

“I was saying these things and weeping in the most bitter contrition of my heart, when suddenly I heard the voice of a boy or a girl I know not which — coming from the neighboring house, chanting over and over again, "Pick it up, read it; pick it up, read it." ["tolle lege, tolle lege"] Immediately I ceased weeping and began most earnestly to think whether it was usual for children in some kind of game to sing such a song, but I could not remember ever having heard the like. So, damming the torrent of my tears, I got to my feet, for I could not but think that this was a divine command to open the Bible and read the first passage I should light upon. For I had heard how Anthony, accidentally coming into church while the gospel was being read, received the admonition as if what was read had been addressed to him: "Go and sell what you have and give it to the poor, and you shall have treasure in heaven; and come and follow me." By such an oracle he was forthwith converted to thee.

“So I quickly returned to the bench where Alypius was sitting, for there I had put down the apostle's book when I had left there. I snatched it up, opened it, and in silence read the paragraph on which my eyes first fell: "Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying, but put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh to fulfill the lusts thereof." I wanted to read no further, nor did I need to. For instantly, as the sentence ended, there was infused in my heart something like the light of full certainty and all the gloom of doubt vanished away.

Augustine’s Ordination

After his conversion and baptism, Augustine retired to a monastery and later returned to Africa, where he spent some years at his family estate before being ordained as a priest. St. Augustine was consecrated as bishop in A.D. 395. According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy:“Augustine, intent on breaking wholly with his old life, gave up his position, and wrote to Ambrose to ask for baptism. The months which intervened between that summer and the Easter of the following year, at which, according to the early custom, he intended to receive the sacrament, were spent in delightful calm at a country-house, put at his disposal by one of his friends, at Cassisiacum (Casciago, 47 m. n. by w. of Alilan). Here Monnica, Alypius, Adeodatus, and some of his pupils kept him company, and he still lectured on Vergil to them and held philosophic discussions. The whole party returned to Milan before Easter (387), and Augustine, with Alypius and Adeodatus, was baptized. Plans were then made for returning to Africa; but these were upset by the death of Monnica, which took place at Ostia as they were preparing to cross the sea, and has been described by her devoted son in one of the most tender and beautiful passages of the Confessiones.

Augustine remained at least another year in Italy, apparently in Rome, living the same quiet life which he had led at Cassisiacum, studying and writing, in company with his countryman Evodius, later bishop of Uzalis. Here, where he had been most closely associated with the Manicheans, his literary warfare with them naturally began; and he was also writing on free will, though this book was only finished at Hippo in 391. In the autumn of 388, passing through Carthage, he returned to Thagaste, a far different man from the Augustine who had left it five years before. Alypius was still with him, and also Adeodatus, who died young, we do not know when or where. Here Augustine and his friends again took up a quiet, though not yet in any sense a monastic, life in common, and pursued their favorite studies. About the beginning of 391, having found a friend in Hippo to help in the foundation of what he calls a monastery, he sold his inheritance, and was ordained presbyter in response to a general demand, though not without misgivings on his own part. /~/

“The years which he spent in the presbyterate (391-395) are the last of his formative period. The very earliest works which fall within the time of his episcopate show us the fully developed theologian of whose special teaching we think when we speak of Augustinianism. There is little externally noteworthy in these four years. He took up active work not later than the Easter of 391, when we find him preaching to the candidates for baptism. The plans for a monastic community which had brought him to Hippo were now realized. In a garden given for the purpose by the bishop, Valerius, he founded his monastery, which seems to have been the first in Africa, and is of especial significance because it maintained a clerical school and thus made a connecting link between monastics and the secular clergy. Other details of this period are that he appealed to Aurelius, bishop of Carthage, to suppress the custom of holding banquets and entertainments in the churches, and by 395 had succeeded, through his courageous eloquence, in abolishing it in Hippo; that in 392 a public disputation took place between him and a Manichean presbyter of Hippo, Fortunatus; that his treatise De fide et symbols was prepared to be read before the council held at Hippo October 8, 393; and that after that he was in Carthage for a while, perhaps in connection with the synod held there in 394.” /~/

Augustine’s Later Years

Augustine spent the last 35 years of his life in Hippo (later Bone, now Annaba, Algeria), where he lived ascetically, wrote extensively and encouraged his followers to establish religious communities, He founded a community of women, headed his sister. He died in Hippo in A.D. 430 while it was being besieged by Vandals.

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “The intellectual interests of these four years are more easily determined, principally concerned as they are with the Manichean controversy, and producing the treatises De utilitate credendi (391), De duabus animabus contra Manichaos (first half of 392), and Contra Adimantum (394 or 395). His activity against the Donatists also begins in this period, but he is still more occupied with the Manicheans, both from the recollections of his own past and from his increasing knowledge of Scripture, which appears, together with a stronger hold on the Church's teaching, in the works just named, and even more in others of this period, such as his expositions of the Sermon on the Mount and of the Epistles to the Romans and the Galatians.

"Full as the writings of this epoch are, however, of Biblical phrases and terms,-grace and the law, predestination, vocation, justification, regeneration-a reader who is thoroughly acquainted with Neoplatonism will detect Augustine's avid love of it in a Christian dress in not a few places. He has entered so far into St. Paul's teaching that humanity as a whole appears to him a massa peccati or peccatorum, which, if left to itself, that is, without the grace of God, must inevitably perish. However much we are here reminded of the later Augustine, it is clear that he still held the belief that the free will of man could decide his own destiny. He knew some who saw in Romans ix an unconditional predestination which took away the freedom of the will; but he was still convinced that this was not the Church's teaching. His opinion on this point did not change till after he was a bishop. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu /~/]

“The more widely known Augustine became, the more Valerius, the bishop of Hippo, was afraid of losing him on the first vacancy of some neighboring see, and desired to fix him permanently in Hippo by making him coadjutor-bishop,-a desire in which the people ardently concurred. Augustine was strongly opposed to the project, though possibly neither he nor Valerius knew that it might be held to be a violation of the eighth canon of Niema, which forbade in its last clause " two bishops in one city "; and the primate of Numidia, Megalius of Calama, seems to have raised difficulties which sprang at least partly from a personal lack of confidence. But Valerius carried his plan through, and not long before Christmas, 395, Augustine was consecrated by Megalius. It is not known when Valerius died; but it makes little difference, since for the rest of his life he left the administration more and more in the hands of his assistant. Space forbids any attempt to trace events of his later life; and in what remains to be said, biographical interest must be largely our guide. We know a considerable number of events in Augustine's episcopal life which can be surely placed-the so-called third and eighth synods of Carthage in 397 and 403, at which, as at those still to be mentioned, he was certainly present; the disputation with the Manichean Felix at Hippo in 404; the eleventh synod of Carthage in 407; the conference with the Donatists in Carthage, 411; the synod of Mileve, 416; the African general council at Carthage, 418; the journey to Caesarea in Mauretania and the disputation with the Donatist bishop there, 418; another general council in Carthage, 419; and finally the consecration of Eraclius as his assistant in 426.” /~/

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024