PASSION OF CHRIST

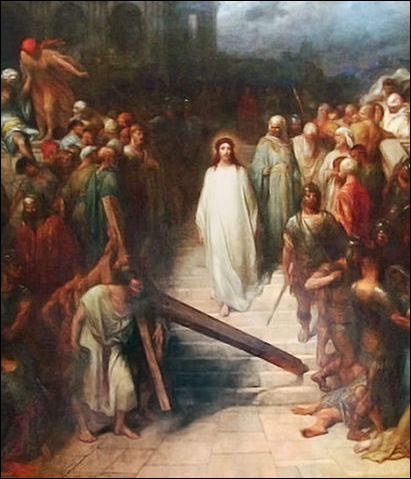

Christ Carrying the Cross by El Greco

The word "passion" is derived from he Latin word “passus” which means “having suffered” or “having undergone.” According to the BBC: “The Passion of Christ is the story of Jesus Christ's arrest, trial and suffering. It ends with his execution by crucifixion. The Passion is an episode in a longer story and cannot be properly understood without the story of the Resurrection. The word Passion comes from the Latin word for suffering. The crucifixion of Jesus is accepted by many scholars as an actual historical event. It is recorded in the writings of Paul, the Gospels, Josephus, and the Roman historian Tacitus. Scholars differ about the historical accuracy of the details, the context and the meaning of the event. Most versions of the Passion begin with the events in the Garden of Gethsemane. Some also include the Last Supper, while some writers begin the story as early as Palm Sunday, when Jesus entered Jerusalem to the applause of the crowds. [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

“The Passion is a story about injustice, doubt, fear, pain and, ultimately, degrading death. It tells how God experienced these things in the same way as ordinary human beings. The most iconic image of the Passion is the crucifix - Christ in his last agony on the cross - found in statues and paintings, in glass, stone and wooden images in churches, and in jewellery. The Passion appears in many forms of art. It is set to music, used as a drama and is the subject of innumerable paintings. |::|

“Spiritually, the Passion is the perfect example of suffering, which is one of the pervasive themes of the Christian religion. Suffering is not the only theme of the Passion, although some Christians believe that Christ's suffering and the wounds that he suffered play a great part in redeeming humanity from sin. |::|

“Another theme is incarnation - the death of Jesus shows humanity that God had become truly human and that he was willing to undergo every human suffering, right up to the final agony of death. Another is obedience - despite initial, and very human, reluctance and fear, Jesus demonstrates his total acquiescence to God's wishes. But the final theme is victory - the victory of Christ over death - and this is why the Passion story is inseparable from the story of the Resurrection. |::|

“The main episodes of the Passion story are:

The Last Supper

The agony in the Garden of Gethsemane

The arrest of Jesus after his betrayal by Judas

The examination and condemnation of Jesus by the Jews

The trial before Pilate during which Jesus is sentenced to be whipped and crucified

The crucifixion of Jesus |::|

RELATED ARTICLES:

LAST SUPPER, ARREST OF JESUS AND EVENTS BEFOREHAND

TRIALS OF JESUS africame.factsanddetails.com

TRIALS OF JESUS factsanddetails.com

PONTIUS PILATE: HIS CRUELTY, HISTORY AND ROLE IN THE DEATH OF JESUS africame.factsanddetails.com

CRUCIFIXION OF JESUS, EVENTS AND THE STATIONS OF THE CROSS africame.factsanddetails.com

CRUCIFIXION: HISTORY, EVIDENCE OF IT AND HOW IT WAS DONE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Jesus and the Historical Jesus Britannica on Jesus britannica.com Jesus-Christ ; PBS Frontline From Jesus to Christ pbs.org ; Life and Ministry of Jesus Christ bible.org ; Jesus Central jesuscentral.com ; Catholic Encyclopedia: Jesus Christ newadvent.org ; Complete Works of Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org ; Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Answers christiananswers.net ; Bible: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks Biblical History: Bible History Online bible-history.com ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Trial and Crucifixion of Jesus, The: Texts and Commentary Paperback” by David W. Chapman, Eckhard J. Schnabel Amazon.com ;

“What Christ Suffered: A Doctor's Journey Through the Passion” by Thomas W McGovern MD Amazon.com ;

“The Crucifixion of Jesus: A Medical Doctor Examines the Death and Resurrection of Christ” by Joseph Bergeron M.D. Amazon.com ;

“The Crucifixion of Jesus, Completely Revised and Expanded: A Forensic Inquiry”

by Frederick T. Zugibe Amazon.com ;

“The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ” by Fleming Rutledge Amazon.com ;

“The Crucifixion of the King of Glory: The Amazing History and Sublime Mystery of the Passion” by Eugenia Scarvelis Constantinou PhD, Eugenia Scarvelis Constantinou, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection”

by Pope Benedict XVI, Matthew Arnold, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus” by Colin J. Humphreys Amazon.com ;

“Jesus and the Last Supper” by Brant Pitre Amazon.com ;

“Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Supper”

by Brant Pitre and Scott Hahn Amazon.com ;

“Jesus on Trial: A Lawyer Affirms the Truth of the Gospel” by David Limbaugh, Walter Dixon, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Trial of Jesus from a Lawyer's Standpoint: Complete” by Walter M. Chandler Amazon.com ;

“Pontius Pilate” by Ann Wroe Amazon.com ;

“The Resurrection of Jesus: Apologetics, Polemics, History” by Dale C. Allison Jr, Jim Denison, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus” by Michael R. Licona, Gary R. Habermas, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Church of the Holy Sepulchre: The History of Christianity in Jerusalem and the Holy City’s Most Important Church” by Kosta Kafarakis Amazon.com ;

“The Architectural History of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem” by Robert Willis Amazon.com

Passion Story According to the Gospels

Christ Carrying the Cross

“The Passion story is told in the 4 Gospels of the New Testament of the Bible (Mark 14-15, Matthew 26-27, Luke 22-23, and John 18-19). The first 3 (often called the Synoptic Gospels) have much in common, while St John's Gospel tells the story rather differently. |::|

According to the BBC: “Many Bible scholars would say that the Gospels are not primarily a historical record of what happened because: 1) they were written between 40 and 70 years after the death of Jesus: 2) those who wrote them were not present at the events they described - but the oral tradition was very strong in those days, so it was possible for information to be passed on quite accurately from actual eyewitnesses; 3) the oral tradition allowed the narrative to be reshaped as it was passed on, in order to suit the purposes of the person telling the story; 4) the Gospels differ on some of the events; 5) the purpose of the Gospels is not to provide an accurate record of the historical events of Christ's last days but to record the spiritual truth of Jesus Christ; 6) The Gospels are a combination of historical fact with theological reflection on the meaning and purpose of Christ's life and death. [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

“They also look back to show how Christ's suffering and death followed the prophecies of the Old Testament in order to demonstrate that he was the long-expected Messiah. The Gospel accounts of the Passion are very simple; other accounts of Christ's suffering and death have embellished the story with additional details. |::|

Way of Sorrow

Via Dolorosa, in the Muslim and Christian Quarters in the Old City of Jerusalem, is route taken be Jesus, from the moment he was he was sentenced to his crucifixion. It begins near the Lion's Gate (St Stephen’s Gate), the entrance of the Old City facing the Mount of Olives, and follows a more or less straight course, with a zigzag n the middle, to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, which contains the tomb of Jesus. Along the way are fourteen so-called stations, most of which correspond with events described in the New Testament. Via Dolorosa means the “Sorrowful Street” in medieval Latin but is often called the “Way of the Cross.”

The Via Dolorosa has no basis in historical fact. The “Holy Places” were discovered in the 4th century, 300 years after Christ’s death by the Empress Helena and the Via Dolorosa was not created until long after that, most likely in the 15th century. By then the entire layout of the city was different than in Jesus’s time. Some have suggested that route was chosen by medieval merchants to bring them business from pilgrims.

From what historians and archaeologists can best determine Jesus was tried by Pilate near where the Armenian Church is today not near the Lion Gate, where the Via Dolorosa begins. Jesus He carried the crossbeam of his cross, not the whole thing, down St. James Road and up Chabad Street, the Cardo Maximus of the Romans, the Garden Gate, which stood where David Street hits the bazaars today. Most of the sights are looked after by Greek Orthodox monks and Franciscan friars and nuns.

At 4:00pm on Good Friday, during Holy Week, thousands of Christians from all over the world rent robes and crosses and parade through the streets of Jerusalem , following the route of Jesus, singing, chanting, reading passages from the bible and stopping at the 14 stations on Via Dolorosa. Sometimes individuals carrying smaller crosses, follow the entire route on their knees. "My faith became gigantic,” one pilgrim told National Geographic. "We felt Him walking among us."

Dan Belt wrote in National Geographic, “Christians form all over the world pour in like a conquering horde surging down the Via Dolorosa’s narrow streets and ancient alleyways, seeking communion in the cold stones or some glimmer, perhaps, of the agonies Jesus endured in his final hours. Every face on earth seems to float through the streets... every possible combination of eye and hair and skin color, every costume and style of dress, from blue-back African Christians in eye-popping daskikis to pale Finnish Christians dressed as Jesus with a bloody crown of thorns to American Christians in sneakers.

Stations of the Via Dolorosa

1) The first station is at Antonia — a Roman Fortress and headquarters for the Roman high priest in Jesus' day — where Jesus was condemned and Pilate washed his hands of the guilt . The Antonia is long gone; a playground in an Arab high school — Madrasa al-Omariya, 300 meters west of the Lion's Gate — is said to be a courtyard of the Antonia. From here the route then follows a busy narrow street that parallels’s north wall of Herod’s Great Temple through the Muslim Quarter.

Via Dolorosa

2) The second station is located next to the Franciscan Monastery of the Flagellation, across the road from the First Station. This is where Christ took up his cross and was whipped on Pilate’s orders. The chapel was built on the site of a Crusader church but mostly it dates back to the 1920s. The Chapel of the Condemnation and Imposition of the Cross on the left, marks the site where Jesus was sentenced to death and soldiers gambled for Jesus' clothes.From here, the Via Dolorosa turns south on Tariq Bab al-Ghawanima and passes the northwestern gate of the Temple Mount. Just west of the entrance to the Lithostratos is the Ecce Homo Arch, where Pilate identified Jesus to the crowd saying "Ecco homo" ("Behold the man" - John 19:5).

3) The Third Station is where Jesus fell for the first time under the weight of his cross. 4) The Forth Station is where Mary watched her son go by with the cross, and is commemorated at the Armenian Church of Our Lady of the Spasm. (Neither of these events is recorded in the Bible.) 5) The Fifth Stations mark place where Jesus faltered and was offered a drink. At Station 5, Simon of Cyrene was forced by Roman soldiers to help Jesus carry this cross (Mt 27:32; Mk 15:21; Lk 23:26).

6) The Sixth Station at the top of a steep hill is where Veronica wiped the sweating face of Jesus with a handkerchief. The Greek Catholic Church of St. Veronica is located here. According to a tradition dating from the 14th century, St. Veronica wiped Jesus' face with her handkerchief, leaving an image of his face imprinted on the cloth. The relic, known as the Sudarium or Veronica, is kept at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Veronica's name may derive from the Latin vera icon, "true image."

7) The Seventh Station is where Jesus fell for a second time and was jabbed with a lance by a Roman centurion. This is marked by a Franciscan chapel at the Via Dolorosa's junction with Souq Khan al-Zeit. 8) The Eight Station marks the place where Jesus consoled the lamenting women of Jerusalem (Lk 23:27-31). 9) The Ninth Station marks the site of Jesus' third fall. A Roman pillar at the Coptic Patriarchate next to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre marks the site.

The last five stations are in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Ten through Thirteen take place in Golgotha, where Jesus was crucified. These include the 10) The Tenth Station, where Jesus was stripped (at top of the stairs to the right outside the entrance); and 11) The Eleventh Station, where Jesus was nailed to the cross (upstairs just inside the entrance at the Latin Calvary). 12) The Twelfth Station is where Jesus died on the cross. Here there is a fissure in the limestone, produced, it is said, by an earthquake that occurred when Jesus died (Rock of Golgotha in the Greek Orthodox Calvary). 13) The Thirteenth Station is where Jesus was taken down from the cross and his body was placed a stone. The statue of Our Lady of Sorrows sits next to the Latin Calvary. 14) The Fourteenth and Last Station is where Jesus was laid in the tomb. The tomb is in the edicule (a small building) on the main floor, inside the tiny Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre.

Way of Sorrow In the Wrong Place?

In 2001, archaeologists announced that they had discovered what they believed was the site of Jesus’s trial — Herod the Great’s Jerusalem palace. The unveiling of this site marks a fine confluence of archeology and biblical text...The only problem is that for hundreds of years tourists have already been visiting the site of the trial of Jesus, in a completely different part of Jerusalem. The Via Dolorosa or “Way of Sorrows,” the road that Jesus is believed to have travelled as he carried his cross from his trial to his crucifixion, is currently at the top of must-see lists of religious attractions for visitors to the city. Each year more than a million Christian pilgrims visit Jerusalem hoping to retrace the steps of the Savior. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 6, 2015]

The Via Dolorosa ends at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and is marked by nine stations of the cross. The first of these commemorates Jesus’s sentencing before Pilate, and is found at the Antonia Fortress, the traditional location for the trial. But the route of the Via Dolorosa, like so many religious sites in Israel, doesn’t have a particularly strong historical pedigree—it was established only in the 18th century

The historical accuracy of the pilgrimage route was always on shaky ground. As it currently stands, the Via Dolorosa follows the account given in the Gospel of John. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the final stop on the Via Dolorosa, is believed by Christians to be built on the site of Jesus’s crucifixion and burial, a place known as Golgotha.

The original site of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was identified in a moment of inspiration by Helena, mother to the Roman emperor Constantine, on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the fourth century. But there is a problem with its location. The Bible clearly specifies that Jesus was executed outside the city walls; the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is inside the walls. Even in the medieval era this disparity made Christians uncomfortable. As a result, Protestant Biblical archeologists identified a second site, known today as the Garden Tomb, as the actual place of Jesus’s death and burial. The historical accuracy of this second site is also hotly contested, but it remains a popular pilgrimage site for Protestants to this day. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 6, 2015]

As Mark Goodacre, Professor of New Testament at Duke University, told the Daily Beast, “The Gospel writers have little interest in the precise location of Jesus’ trials. Writing a generation or more after the events they are describing, and at some geographical distance, it is unlikely that they provide us with the kinds of clues that we would like to see. So while this discovery is exciting, we should be cautious about over-stating its importance for studying the historical Jesus.” Tradition has the beginning of the Via Dolorosa wrong, and probably the end too; it’s safe to say that the stuff in between probably doesn’t pan out either. In short, we don’t know the route that Jesus walked or the location of Jesus’ tomb.

Passion in Liturgy, Music and Art

.jpg)

According to the BBC: “The Passion of Christ has featured in Christian liturgy since the 4th century. It became an institution in the 5th century when Pope Leo the Great laid down that the St Matthew Passion should be part of the mass on Palm Sunday and the Wednesday of Holy Week, and the St John Passion should be part of the Good Friday service. From the 7th century the service on the Wednesday of Holy Week featured the St Luke Passion, and from the 10th century the Roman Catholic Church used the St Mark Passion on the Tuesday of Holy Week. [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

“From quite early the Passion was chanted in a dramatic way, with the reader representing the different voices in the story: the Evangelist as Narrator, the voice of Christ, and other speaking parts. Very often the words of Christ were chanted while the rest was spoken. The texts were originally chanted by a single person, but from around the 13th century different voices took the different parts. |::|

“The first polyphonic Passion settings date from the 15th century. As music became more sophisticated various forms of Passion were developed, ranging from straight narratives with music through to oratorios anchored to a greater or lesser extent in the text of scripture. The St Matthew Passion of J S Bach is probably the best-known of the musical settings of the Passion.” |::|

“The Passion is one of the most common subjects in art. Paintings of the Crucifixion were much in demand for church use. The earliest paintings of the Crucifixion date from the 5th century. Among the most famous paintings is the Isenheim altarpiece (1515) by Mathias Grunewald. The painting of the Crucifixion is gruelling in both its detailed treatment of the physical anguish of Jesus, and the visual language used. The Crucifix as a sculpted cross with the figure of Jesus dates from the 10th century (the Gero Cross of Cologne Cathedral). In many churches a Crucifix stands on the choir screen, in the arch between the nave and the chancel. These are often known as 'roods' and the screen as a 'rood screen'. Rood comes from the Saxon word for a crucifix.” |::|

Passion Plays and Miracle Plays

Christ entering Jerusalem, Oberammergau Passion Play in 1900

Passion plays, mystery plays and miracle plays were introduced in the Middle Ages to Mass, celebrations and festivals to entertain and offer theological instruction to people who were mostly illiterate. Passion plays usually dealt with events dealing with the death and resurrection of Christ. Mystery plays dramatized events from the Old and New Testaments such as Adam and Eve, Noah, Abraham almost sacrificing of Isaac, and Jesus being tempted by the Devil. Miracle plays were usually centered on the lives of famous saints or events in their lives. Moral plays were stories with a moral messages.

These plays grew out living pictures (tableaux) of things like the Three Wise Men visiting Bethlehem. The earliest miracle plays are believed to date pack to the 10th century but the first one recorded by name, “ Play of St. Katherine” , was produced in England in the 12th century.

Early plays were performed in Latin in churches. Later they were performed in local languages in open spaces such as public squares. Freed from the church, they incorporated non-religious elements such as comedy and satire and dealt with issues of the day and controversial subjects. Sometimes they made fun of the church and dealt with sexual themes and ended up being condemned by the church. .

See Separate Article: OBERAMMERGAU PASSION PLAYeurope.factsanddetails.com

Old Testament and Other Religious Contribution to the Passion

According to the BBC: “Some accounts of the Passion use elements from Old Testament passages to provide additional material: One of the most widely known of these applications is the phrase..."they have numbered all my bones" (Psalm 21:18), which lay behind a host of narrative descriptions of Christ being stretched so tightly on the cross that all his bones were clearly visible and therefore numerable. “Several passages from the Book of Isaiah also provided details that have been added into the Passion story. [Source: Thomas H. Bestul, Texts of the Passion: Latin Devotional Literature and Medieval Society, 1996 |::|

According to the BBC: “It wasn't just the Old Testament material that was used to augment the Passion story. Gospels not included in scripture, such as the Gospel of Nicodemus, provided additional material.Bible commentaries from masters such as Saint Augustine and Saint Jerome dealt with the Passion, while St. Ephraem, for example, added many physical details of the Passion...They, indeed, stretched out His limbs and outraged Him with mockeries. A man whom He had formed wielded the scourge. He who sustains all creatures with His might submitted His back to their stripes — Saint Ephraem [Source: BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

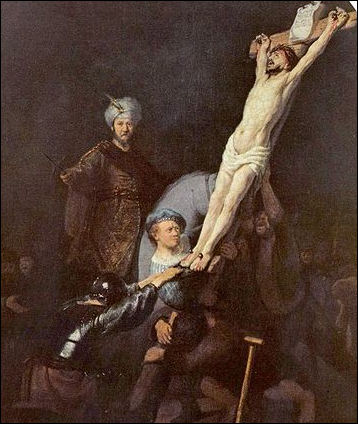

Raising the Cross by Rembrandt“Mediaeval books like the Historia scholastica of Peter Comestor and the Legenda aurea of Jacobus de Voragine (d. 1298) added their own ideas to enhance the power of the story...

John's description of the arrest in the garden states only that the band of soldiers with the tribune and the leaders of the Jews took Jesus and bound him (John 18:12).

In some of the late medieval treatises on the Passion, this description is elaborated with the additional detail that Christ's hands were tied so tightly that blood burst from his fingernails. [Source: Thomas H. Bestul, Texts of the Passion: Latin Devotional Literature and Medieval Society, 1996 |::|

“The mediaeval monk John of Fécamp (died 1078) wrote a famous description of the body of the dying Christ, which clearly inspired many painters... His naked breast gleamed white, his bloody side grew red, his stretched out innards grew dry, the light of his eyes grew faint, his long arms grew stiff, his marble legs hung down, a stream of holy blood moistened his pierced feet. [Source: John of Fécamp, quoted in Thomas H. Bestul, Texts of the Passion: Latin Devotional Literature and Medieval Society, 1996 |::|

“Mel Gibson's film The Passion of the Christ used another influential account; The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, which is based on the visions of the German nun Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774-1824). Emmerich believed she had seen Christ's suffering - and her visions added to the Gospel version of the story. So for example, where the Gospels merely refer to Jesus being flogged, Emmerich adds much detail: |::|

“What the Gospels state matter-of-factly and without narrative elaboration is luridly expanded by Emmerich: First they used "a species of thorny stick covered with knots and splinters. The blows from these sticks tore His flesh to pieces; his blood spouted out...." (p. 135). Then she describes the use of scourges "composed of small chains, or straps covered with iron hooks, which penetrated to the bone and tore off large pieces of flesh at every blow" (p. 135). Emmerich's visions paint a very negative portrait of the Jews, and give them a much greater role in the suffering of Jesus than is found in the Bible. [Source: Paul Kurtz, The Passion as a Political Weapon, Free Inquiry, 2004]

The Passion and Anti-Semitism

“The Passion story has often been used to justify Christian anti-Semitism with cruel, tragic and shaming results. Mary Gordon points out that the Passion is a story whose very power to move the human spirit has been a vehicle for both transcendence and murder. To be a Christian is to face the responsibility for one's own most treasured sacred texts being used to justify the deaths of innocents. [Source: Professor Terry Eagleton, cultural theorist, literary critic and Catholic, BBC, September 18, 2009 |::|]

Christian and Jewish scholar arguing

“And the gospel versions of the story clearly suggest that even if the Jews did not actually kill Jesus, some Jewish officials played a significant part in getting the Roman governor to sentence Jesus to death.Some people claim that the Bible states that the Jews cursed themselves as Christ-killers. They base this on a passage in St. Mark's Gospel (27:25) where members of the Jewish crowd shout out, "His blood be on us, and on our children." This phrase was used for centuries to claim that Jews bore a 'blood guilt' that justified Church anti-Semitism and the murder of Jews. In fact Jesus was not killed by the Jews, but by Roman soldiers on the orders of Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor.

“Jesus was crucified, and only the Romans used this method of execution. Jesus was not primarily executed for blasphemy but because Pilate feared that he would incite public unrest. Some of the Jewish leadership played a part in the death of Jesus, but the Jewish population as a whole had nothing to do with it. The blame for Christ's death is unambiguously stated in the Christian Creed: He was also crucified for us, suffered under Pontius Pilate and was buried. |::|

“The Roman Catholic Church brought a formal end to Church anti-Semitism at the Second Vatican Council when it declared in the document Nostra Aetate: True, the Jewish authorities and those who followed their lead pressed for the death of Christ, still what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today. |::|

“Although the Church is the new People of God, the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures.” |::|

Mel Gibson's The Passion

One film about Jesus that stirred up more than its share of controversy and generated a lot of press was “The Passion of the Christ” , a film made by Mel Gibson in which all the actors spoke Aramaic (the language widely spoken in Jesus’s time), Hebrew or Latin and highlighted the violence of Christ’s last 12 hours in lurid detail with no shortages of blood, whips, chains, thorns, ripped open flesh, anguished expressions and nails being driven through body parts.

Audiences loved the film. Some viewers said that watching it was like a religious experience that reveled new level of their faith. One audience member told Newsweek, “I left the theater beaming and smiling and so renewed.” Pope John Paul II said, “It is as it was.” The Reverend Billy Graham wept. Yasser Arafat called it “moving and historical.” Some local religious leaders bought tickets for their entire congregations. The box office numbers were quite impressive. It grossed $350 million in the United States and $550 million worldwide in the first month after its release.

Most critics panned it. Charges of anti-Semitism were made in the way the Jews were portrayed as ultimately being responsible for all the pain that Jesus endured. Gibson is very conservative “traditionalist Catholic” who rejects the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, which declared that the Jews should not be held responsible for Christ’s death. When “The Passion” was ignored at the Oscars some blamed Jews in Hollywood for the snub. Gibson’s views on Jews was called into question when he said “*#&#! Jews” were responsible for “all the wars in the world” when he was arrested for drunk driving California in August 2006.

“The Passion” was shot in the Italian town of Matera and was rejected by most Hollywood studios. Gibson plucked down $30 million of his own money to make it and said “the Holy Ghost was working through me on this film.” The actor who played Jesus said of Gibson: “The wounds of Christ healed his wound.” There were a number of historical inaccuracies: most Romans in Palestine spoke Greek rather Latin; people who were crucified were nailed through wrists and ankles rather feet and hands. Gibson also included some scenes in the movie that were not in the Gospel, some them suggesting Jewish culpability.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, 1994); Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024