CLOTHES IN THE ARAB WORLD

woman's abaya worn by a Saudi woman

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. wrote in “A Concise History of the Middle East”: “People's clothing had to meet stiff requirements for modesty and durability. Linen or cotton clothes were worn in hot weather and woolen ones in the winter — and at all times of the year by some mystics and nomads. Loose-fitting robes were preferred to trousers, except by horseback riders who wore baggy pants. [Source: Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., “A Concise History of the Middle East,” Chapter. 8: Islamic Civilization, 1979, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu /~]

“Muslim men covered their heads in all formal situations, either with turbans or various types of brimless caps. Different colored turbans might identify a man's status; for instance, green singled out one who had made the hajj to Mecca. Arab nomads wore flowing kuJyahs (headcloths) bound by headbands. Hats with brims and caps with visors were never worn by Muslims, because they would have interfered with prostrations during worship. Women always wore some type of long cloth to cover their hair, if not also to veil their faces. /~\

Many African Muslims wear amulets with passages of the Qur’an. “Christians, Jews, and other minorities wore distinctive articles of clothing and headgear. If what you wore showed your religion and status, as did the attire of a stranger you might meet in the bazaar, each of you would know how to act toward the other.” /~\

Websites and Resources: Arabs: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Who Is an Arab? africa.upenn.edu ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Arab Cultural Awareness fas.org/irp/agency/army ; Arab Cultural Center arabculturalcenter.org ; 'Face' Among the Arabs, CIA cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence ; Arab American Institute aaiusa.org/arts-and-culture ; Introduction to the Arabic Language al-bab.com/arabic-language ; Wikipedia article on the Arabic language Wikipedia

Bedouin Clothes

Sun and sand protection is the primary objective with Bedouin clothes. Bedouin garments can be wrap around the wearer to keep the sand and sun out. Loose clothing tends to shield the skin from sun and provide enough open space that heat absorbed by the cloth is not directly transferred to the skin.

Each Bedouin tribe member wears slightly clothes to indicate locality, social position and marital status, with these things usually being indicated by embroidery on their cloak, headdresses, jewelry and hairstyle worn on special occasions. Each tribe has is own designs that are worn on their clothes, Tents and camels bags also carry these designs so that caravans can be identified from a distance.

A typical Bedouin man wear a white cotton foot-length, long-sleeve shirt, an aba (a long khaki ankle-length sleeveless robe), and red tasseled sash. Sometimes they wear a dagger in their belt. At night the aba is used a blanket. In many places Bedouin men wear a thobe (a long white gown). Sometimes they wear a long sleeve coat called a gumbaz or kibber over the thobe.

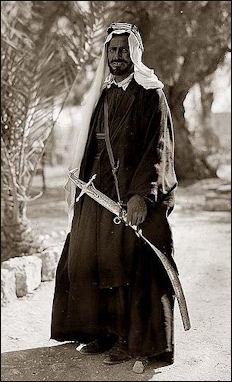

men's abaya worn by a Bedouin man

Bedouin men tend to wear camel hide sandals, ankle boots or Western-style shoes. Some go barefoot in the hot sand. To make standing in the hot sand bearable sometimes they stand on one and then alternate back and forth with the other foot. If they step on a thorn they use another thorn to dig it out.

On their head Bedouin men wear a Yasser-Arafat-style keffiyeh , which can be draped under the chin, lifted across the face for protection against sandstorms, or crossed under the chin and fixed on top of the head for warmth. The cloth headdress held in place by a thick wool cord of made of black goat hair. When it is cold he may wear a round wool cap under the a keffiyeh .

Women wear dark clothes and a kerchief held in place with a band of folded cloth. Red is usually worn by married women while blue is worn by unmarried women. Loose cloaks, or thobe , are worn for special events. These often feature embroidery around the neckline, sleeves and hems. Veils are often connected to a turban and are decorated with silver coins. Everyday clothes are much plainer. Bedouin women usually wear sandals.

Some Bedouin women wear a burqua , a mask-like veil that reveals only the eyes and neck and has a narrow ridge that runs down the middle of the face and looks like something an ax-murderer would wear. For a woman wearing such a garment only immediate relatives are allowed to see her face. Bedouin women in Saudi Arabia wear a black tent-like cloak over their clothes and a mask that covers the entire faces except for small eyes slits. In the desert most Bedouin women don't wear veils because they are is simply too hot. They don them when strangers appear.

Najaf Abaya Makers In Decline

The Najafi Abaya, a hand-made traditional Arab cloak for men made in the city of Najaf, south of Baghdad, and the fabrics from which they were made, were for a long time the desired cloak worn by Arab VIPs from officials to oil-rich sheikhs. But now the producers of these garments are increasingly going out of business. [Source: AFP, March 10, 2011 */]

AFP reported: “The men who produce the hand-made cloth, inheritors of a generations-old trade, are increasingly going out of business. “Let me tell you something,” said Kadhim, laughing bitterly while embroidering one of the full-length cloaks, spread across his lap. “If I could find a government job, I would stop all this. “This work is too hard, and business is not good anymore.” The bazaar where Kadhim has his shop, at the entrance to the shrine to Imam Ali, revered among Shia, was once dominated by makers of this traditional garb. */

“Now many stalls sell trinkets, toys and other forms of clothing to pilgrims from mainly Shia Muslim Iran, as the tradition of hand-made abayas – those designed and sold in Najaf are only for men – has seen a dramatic decline in recent years. The 41-year-old Kadhim, whose family has been in the business so long that he takes the last name Abu Chengal or “father of the crochet hook”, does not know if he can hang on much longer. “My sales of the summer abaya are down to around a fifth of what they were 10 years ago – I used to sell hundreds but now I sell dozens,” he moaned. */

fashionable abaya

The 2003 US-led invasion that ousted Saddam Hussein unleashed a number of changes, from ending the UN trade embargo on Iraq and lifting the country's own protectionist policies to pushing up the value of the Iraqi dinar. The unrest itself caused a sudden drop in demand for abaya, as fewer customers dared venture to Najaf. And for what orders remained, traditional abaya weavers and tailors found themselves dramatically undercut, prompting many to scramble for secure government jobs. */

“The new competition came not only from imported textiles, now flooding the market alongside other imported goods, but from improvements in abaya cloth produced in domestic factories and much cheaper than its hand-made counterpart. While an embroidered hand-made abaya sells in Najaf's market for between 500,000 and 800,000 Iraqi dinars ($425-$675), factory-made or imported ones can be bought for as little as 75,000 dinars ($65). “When I quit a few years ago, I was selling each abaya cloth for 120,000 to 150,000 dinars ($100-$125),” lamented Hussein Sayed, 63, a weaver who left the trade in 2005. */

“The hand-made item is labour-intensive, he pointed out, taking one worker three to 10 days to weave cloth for one abaya, even before it is embroidered. Meanwhile, “you could buy a piece of cloth for an abaya for 20,000 dinars ($17) – that price was too low, I could not compete,” said Sayed. “As soon as international trade began, our jobs were finished.”Four of his six sons learned the craft but are now taxi drivers. */

“Razzaq Muhammad, 58, told a similar story – he dropped weaving to open a general store in 2006 when the craft no longer generated sufficient income. “It was all we did, my family has done this for more than 100 years – I opened my eyes at birth, and my family was making abayas this way,” he said, standing by three looms kept in a separate room of his home. “The sheikhs, the VIPs, they still want hand-made Najafi abayas. But the work is not continuous, it is not dependable.”His son Ahmed, 31, still practices the craft, painstakingly unknotting yarn made from sheep wool, warping the loom and weaving abaya panels on the old frame with its series of weights and pulleys affixed to the wall and ceiling. But the amount of work on offer is not enough. “I will leave all this if I find another job that covers the needs of my family,” Ahmed said. */

“Hassan Issa al-Hakim, who teaches Islamic history at Kufa University in Najaf's twin city, said the industry dates back more than 150 years and the Najafi abaya “represents the identity of the city”. “It was a gift that would be given to political and religious leaders who visited, and it used to be exported across the region,” the 69-year-old said. Even now, “there are those who make amazing hand-made abayas but they all depend on requests from clients.”Back in the “abaya market”, as it is still called, Kadhim sat alongside his friend Ahmed al-Ghazali, both life-long abaya tailors. “Look here,” Kadhim said waving into the bazaar. "All of this used to be for selling abayas."” */

Japanese Fabric Makers Make Inroads in the Middle East

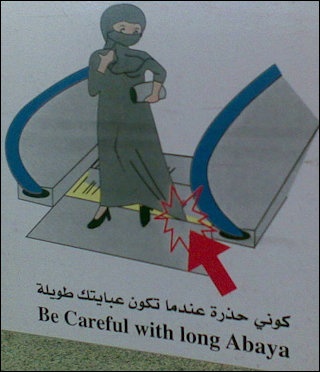

escalator warning

In 2016, Nikkei reported: “Japan's Mitsubishi Rayon, Kuraray and other leading fabric makers are preparing to enhance sales of their quality materials to the Middle Eastern market, to be used for traditional garments. Made-in-Japan fabrics, many of them featuring cutting-edge, high-performance materials, have gained popularity there for their soft and rich texture and wrinkle-resistant convenience. Now that economic sanctions to Iran have been lifted, manufacturers are eager to enter the large and promising market. [Source: Nikkei, March 28, 2016 ~]

“Prices of these garments — black "abaya" for women, and men's white "thobe" robes — can cost from a few dozen to a thousand dollars each. Japanese fabrics are a popular choice for expensive items. According to Kuraray, fabrics from Japan sell for at least $5 per meter, more than double the price of those from Indonesia and South Korea. Japan supplies some 30% of materials used for thobe, and about 10% for abaya. ~

“Mitsubishi Rayon will start enhancing its sales chain in the Middle East as early as this year, hoping to tap into the strong demand for fabrics for abaya. The company currently exports to Saudi Arabia and Dubai its unique tri-acetate fabric, of which about 10% is used for abaya. Mitsubishi Rayon's silk-like tri-acetate has become recognized as one of the finest such fabrics in the Middle East. Keiichi Uno, a board member of Mitsubishi Rayon Textile, has high expectations for Iran's market of 70 million people. "Following the scrapping of sanctions, demand for high-quality clothing materials will surge," he said. ~

“Kuraray, meanwhile, already accounts for half of the abaya fabric supplied by Japanese manufacturers. The company has begun selling its soft and wrinkle-resistant fabrics for thobe, in Dubai and other locations. It plans to boost shipments of garment fabric to the Middle East by 30%. With this effort, it has laid out a sales target for its subsidiary Kuraray Trading at 130 billion yen ($1.14 billion) for the year ending December 2017. This is a 10% increase from the 2015 result. Osaka-based Shikibo, which also sells fabric for thobe, plans to enter the market with a wider selection of products. It is preparing to sell sandals and other clothing accessories. ~

“Hit hard by the current weak crude oil prices, Middle Eastern economies are not as strong as they were. But the demand for the "made-in-Japan" fabrics has remained steady, and some manufacturers are even unable to fully fill orders from the region. According to a United Nations estimate, the population of the Middle East, including Iran, and surrounding western Asian countries, together surpassed 336 million in 2015, and the number will grow roughly 40% to 487 million by 2050. This indicates that the market will remain promising for these fabric suppliers over the medium to long term.” ~

Men’s Clothes

Arab men in parts of the Middle East have traditionally worn a “galabia” (a knee-length shirt), worn loosely or fastened around the waist with a leather belt. Sometimes they wear baggy pants underneath. When its cold they wear a floor-length tunic or an “abaya” (a long, open, coat made of camel hair or wool). Men sometimes wear expensive watches but they generally don’t wear jewelry. Men wear silver wedding rings rather than gold ones in accordance with the Muslim prohibition of wearing gold. The tarboosh once signified a citizen of the Ottoman Empire. It is still worn by some elderly Arabs in some places.

Many Arab Muslim men, especially in Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf states, wear a “thobe” (a long white gown). The thobe ca be made of cotton or linen and is usually white but can be blue, grey, beige.or another color. A thobe is typically ankle-length and loosely covers the body. The top is usually tailored like a shirt. Non-white colors are usually worn in winter. A 'sarwal' or pyjama is typically donned underneath. Sometimes men wear a long sleeve coat called a “gumbaz” or “kibber” over the thobe. A bisht is a dressier men's cloak that is sometimes worn over the thobe, often by high-level government or religious leaders.

Men’s Head Coverings

Some Muslims believe that men are required to cover their hair for reasons of modesty the same way women do. Exposing one's hair is considered immodest. They wear turbans, skullcaps and other styles of headgear. Turbans, fezes and kaffiyeh are all worn by Muslim men. They have religious, cultural and tribal significance as in addition to offering protection from the sun and weather.

Many Arab Muslim men wear a “gutra” (a folded white or checkered cloth similar) held in place with an “agal” (a black double-corded ringlet). Underneath the gutra is a skullcap. The gutra is usually square or rectangular in shape and white, or checkered red/white or black/white. In some countries, the gutra is called a shemagh, kaffiyah or kuffiyeh and the black chord to hold it in place is called an “iqal”.

Gutras are designed to protect the head and neck from the intense sun. They are more lightweight, and to many, more comfortable than a hat. The are also sometimes worn like scarves or worn over the face during sand and dust storms or in dusty roads. When the weather is especially hot, Arab men warp their head coverings around their heads to stay cool.

The “ kaffiyeh” is often worn over a white skull cap and kept in place by a chord made of camel hair. This chord can be knotted in various ways. Until the early 20th century two types of kaffiyehs were commonly worn: black and white ones worn by bedouins and white ones worn by men in cities and villages. During World War I, the British introduced red-and-white headdresses for the Jordanian army. They became popular throughout the region and now worn by Arabs in many Middle Eastern nations.

Yassar-Arafat-Style Kaffiyeh’s Out of Fashion

Yasser Arafat

Yassar-Arafat-style scarves have long been out of fashion among Palestinians. Most are bought by tourists and many are now produced in China. Reporting from Hebron in the West Bank, Edmund Sanders wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Yasser Arafat turned his trademark black-and-white head scarf into a symbol of Palestinian resistance and aspirations for statehood. But now, with relative peace and improving prosperity, the West Bank's only kaffiyeh factory is struggling to survive. Since 1961, the Hirbawi family's looms have churned out hundreds of thousands of the patterned head scarves made iconic by the late PLO chairman, who was rarely seen without his kaffiyeh. During Palestinian uprisings, kaffiyeh sales soared. These days, though, the scarves look a little dated, like cufflinks or cassette tapes. With the streets relatively calm, Palestinian youths are more apt to reach for hair gel, and political leaders prefer Western-style suits. [Source: Edmund Sanders, Los Angeles Times, September 16, 2010 =|=]

“The heaviest blow came from the West Bank's economic rebound, which opened the region to foreign investment and, for the first time, a flood of cheap Chinese-made imports. The new global competition has all but shut the Hirbawis out of a market they once monopolized. "Palestinians just don't buy from us anymore," says Jouda Hirbawi, 50, who began threading the factory looms as a boy and never dreamed of anything other than taking over the family business. Now he won't allow his children to work there. =|=

“The factory is more of a museum, really. Approaching the building on a Hebron hillside, visitors hear the deafening rhythm of the motorized looms long before entering. BUM bum bum, BUM bum bum, BUM bum bum. Inside, rows of greasy, rattling machines, with their spinning metal gears, rubber belts and wooden sticks, give the dimly lighted factory the air of a 19th century steamboat engine room. Jouda stands over the spools of red and black thread as they slip into the loom like streams of paint down long needles, while a threaded shuttle — shaped like a little canoe — is whacked back and forth by wooden mallets to create the base cloth. He trims the loose threads quickly with a tiny knife, smoothing the patterned fabric as it emerges from the machine. "It takes 30 minutes to make one kaffiyeh," he says. =|=

“Twenty years ago, 15 looms, sometimes operating around the clock, made as many as 700 scarves a day. "The entire market was ours," Jouda says. "We were barely able to supply the locals." Today, they're lucky to make one-tenth that number. All the employees except one have been laid off. Most looms sit idle, coated in dust and rust. When Chinese imports first arrived in the late 1990s, selling for a quarter of the price, the Hirbawis tried to expand by introducing new colors and patterns. Rather than the traditional black-and-white or red-and-white, they experimented with the scarves in orange, purple and green, or with hippie-style psychedelic and Southwestern-looking designs. Before long, the Chinese copied those too. Unable to compete, the family closed down the business in 1997. =|=

“Five years later, the Hirbawis reopened, this time trying to beat the Chinese at their own game. Rather than producing the high-quality product they'd built their reputation on, they slashed the thread count, used blends higher in polyester and cut back on the hand-finishing. As a kaffiyeh purist, Jouda can't hide his disappointment with the threadbare fabric that now rolls off his looms. "You can see and feel the difference," he says, pulling an older, thicker kaffiyeh from his desk drawer and holding it next to a new, nearly transparent version. "It was hard to lower our standards. The stuff we make today is only good for tourists." But even after halving the wholesale price to about $4, the Hirbawis haven't won back any market share. Their scarves retail for about $14, while the Chinese knockoffs sell for about $5. Now most of their business comes from Western tourists and the occasional order from the United States and Europe, where kaffiyehs sometimes enjoy popularity as a fashion novelty or political statement. =|=

Women’s Clothes

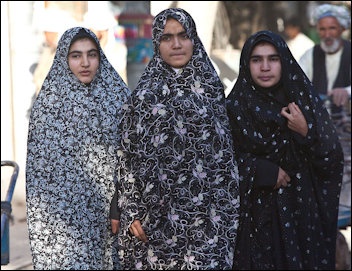

chadors worn by women in Herat, Afghanistan

Ruqaiyyah Waris Maqsood told the BBC: “Sharia does not require women to wear a burqa. There are all sorts of items of dress which are worn by Muslim women, and these vary all over the world. Burqas belong to particular areas of the world, where they are considered normal dress. In other parts of the world the dress is totally different. The rule of dress for women is modesty, the word hijab implies 'covered'. [Source: Ruqaiyyah Waris Maqsood, BBC, September 3, 2009 |::|]

“Some Muslim women feel that they should cover everything from neck to ankle, and neck to wrist. Others also include a head veil (this is the most controversial bit, and millions of Muslim women choose to wear it, or alternatively choose not to wear it - and there is much disagreement between the types!), and finally some choose to cover even their faces, although there is no Islamic text requiring this extreme. My own preference is a long black dress and a white headscarf - I have never worn a burqa in my life. Incidentally, when men try to enforce Muslim dress on women, this is forbidden - no aspect of our faith is to be done by coercion. It is up to the woman what she chooses to do - some choose full hijab and their men hate it! |::|

Many Arab women wear a black tunic-style dress, often with a band of material tied at the waist and a square panel of embroidery at the neck. Baggy trousers are worn under the tunic with shoes or sandals. Some women favor embroidered, floor-length outer garments for Friday prayers and a loose-fitting satin dresses with matching face-cover and waist-length head covering for festive occasions.

“ Yanis” are simple scarfs worn over the head. Tiny safety pins are used to keep head coverings in place. In Iraq athletes have killed for wearing shorts because some consider it un-Islamic to reveal the thighs.

Hijab and Veiling

Hijab describes the veil worn by some Muslim women which covers the head, neck and chest. It has never been common for nomads and the poorer, rural Muslim communities to go veiled. The demands of their lives just made it impractical. So one appeal of veiling to Muslim women has always been that it denotes wealth. It has traditionally been an indication that the woman has married into a family where her husband can afford to keep her at home all day. And in the confines of the home, the veil will come off and women from the wealthy Muslim elites will wear all the best exotic finery that money can buy from the most expensive designer shops in London and Paris.

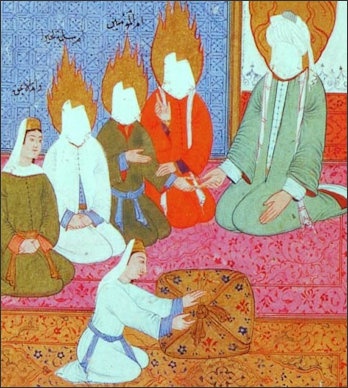

medieval depiction of Muhammad and male and female members of his family

Veiling in Islam has not always been compulsory. In one sample essay on the history and culture of the hijab, the author writes: "Beyond the Near East, the practice of hiding one's face and largely living in seclusion appeared in classical Greece, in the Byzantine Christian world, in Persia, and in India among upper caste Rajput women. Muslims in their first century at first were relaxed about female dress.

There are just two — arguably ambiguous — references in the Qur’an dealing specifically with women's dress, and this has led to different interpretations. The Qur’an’s injunction that Muslim women must "draw their veils over their bosoms" has led to widely varying codes of Islamic dress, or hijab, over many centuries. The Qur’an reads: “O Prophet! Tell thy wives and daughters, and the believing women, that they should cast their outer garments over their persons (when abroad): that is most convenient, that they should be known (as such) and not molested. And Allah is oft-forgiving, most merciful.

It was known that the wives of the Prophet Muhammad covered themselves. However, the Qur’an explicitly states that the wives of the Prophet are held to a difference standard."When the son of a prominent companion of the Prophet asked his wife Aisha bint Talha to veil her face, she answered, ‘Since the Almighty hath put on me the stamp of beauty, it is my wish that the public should view the beauty and thereby recognized His grace unto them. On no account, therefore, will I veil myself’."

See Separate Article HIJAB AND VEILING: HISTORY, CUSTOMS, STYLES AND INTERPRETATIONS OF THE QUR'AN factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018