ECUMENICAL COUNCILS

First Council of Nicaea In the early years of Christianity a great deal of debate, intellectual energy and soul searching went into resolving the questions of how God and Jesus could both be divine if God was one as Jesus himself said and the fact that Jesus must be both human and divine for him to take the place of human kind and die for their sins. The resolution of these questions shaped how Christianity evolved and defined itself.

Ecumenical Councils were called to settle theological issues. Constantine inaugurated the ecumenical movement. He called first general ecumenical council, in Nicaea in A.D. 325 to settle questions of doctrine, combat heresy and work out disputes between different sects. The six Ecumenical Councils that followed — Constantinople 381, Ephesus 431, Chalcedon 451, Constantinople 553, Toledo 598, Constantinople 680 and Nicaea 787 — further defined the doctrines of the church.

At the Council of Ephesus in A.D. 431 several sects were forced to split from the Christian church. At the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 it was declared that God alone could be worshiped and saints were given respect and veneration. At the council in 1054, the Catholic and Orthodox churches split.

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Seven Ecumenical Councils” by Henry R Percival, Philip Schaff, et al Amazon.com ;

“The General Councils: A History of the Twenty-One Church Councils from Nicaea to Vatican II by Christopher M. Bellitto Amazon.com ;

“Decoding Nicea: Constantine Changed Christianity and Christianity Changed the World”

by Paul Pavao, Alan Sisto, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Council of Nicaea” by Young Richard Kim Amazon.com ;

“The Church and the Roman Empire (301–490): Constantine, Councils, and the Fall of Rome” by Mike Aquilina Amazon.com ;

“Cyril of Alexandria and the Nestorian Controversy: The Making of a Saint and of a Heretic” by Susan Wessel Amazon.com ;

“Constantine the Great” by Michael Grant Amazon.com ;

“Constantine the Great: And the Christian Revolution” by G. P. Baker Amazon.com ;

“When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers” by Marcellino D'Ambrosio Amazon.com ;

“Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers” by Andrew Louth and Maxwell Staniforth Amazon.com ;

“Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years” by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Walter Dixon, et al. Amazon.com ;

“A History of Christianity” by Paul Johnson, Wanda McCaddon, et al. Amazon.com

First Four Ecumenical Councils

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote:“The ecclesiastical councils of the fourth and fifth centuries (Nicea, Constantinople, Ephesus, Chalcedon) must always be of profound interest to the Christian Church. On the secular side they represent an important experiment in democracy which stands in sharp contrast to the authoritarian government of the Roman Empire. On the theological side they will always be of paramount interest because they represent the stages by which Christian doctrine was officially formulated. Their results have been universally accepted by almost every branch of Christendom. So important are the theological results of these councils that their other canons are often completely overlooked. On the administrative side their records give us abundant information about the development of the Church. They reflect the rules and disciplines enacted for the organization and lives of Christians. They furnish us with knowledge about the common life of the Church, its method of worship and the conduct expected of its members. Further, the councils enable us to pursue that most fascinating of all studies, the interplay of character. The Councils gave great opportunity for the clash of personal ambitions, and often we see a struggle for a place in the sun combined with the bishops' efforts at defining Truth. And all through them the devout student can see at work the influence of the Spirit of God, moulding men and society according to His will, preserving for succeeding generations the fruits of a reasoned plan of redemption based upon the New Testament writings. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“What made these councils "ecumenical" was not so much the area they represented as the extent of their acceptance. If their conclusions were accepted by the Church as a whole, then and only then were they reckoned as ecumenical. We cannot suppose that everyone who participated in the councils necessarily understood their unique importance. They were all occasional in that they arose out of an immediate situation which demanded attention. But as often happens, in settling an immediate difficulty the councils set the standard for all time. =

“Although the Lutheran Confessions do not explicitly recognize as authoritative the canons of these councils, they do accept the Nicene Creed as a part of the Confessions. The introduction to the Formula of Concord states: ‘Because directly after the times of the apostles, and even while they were still living, false teachers and heretics arose, and symbols, i.e. brief succinct confessions were composed against them in the early Church, which were regarded as teh unanimous, universal Christian faith and confession of the orthodox and true Church, namely the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Athanasian Creed, we pledge ourselves to them, and hereby reject all heresies and dogmas which contrary to them, have been introduced into the Church of God.’” =

First Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325

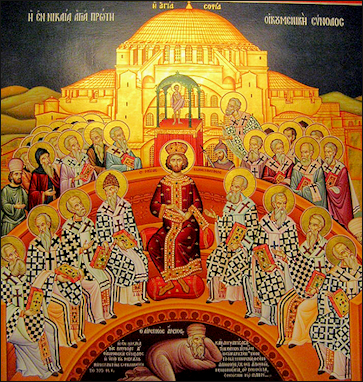

First Council of Nicaea In A.D., 325, the Council of Nicaea, held in Nicaea (present-day Iznik In Turkey), inaugurating the ecumenical movement. Called by Constantine to combat heresy and settle questions of doctrine, it attracted thousands of priests, 318 bishops, two papal lieutenants and the Roman Emperor Constantine himself. The attendees discussed the Holy trinity and the eventual linkage of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, argued whether Jesus was truly divine or just a prophet (he was judged divine), and decided that Easter would be celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox.

Nicaea is not far from Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). After originally being scheduled to meet in Ancyra (also in Turkey), the council was moved to Nicaea, where 318 bishops met in June 325 A.D. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In the ancient world, Nicaea was a locus for commerce and politics. It was part of the Roman province of Bithnyia and Pontus and competed with rival city Nicomedia for the seat of the Roman governor (a kind of ancient capital city). Though it was sacked in the third century, by the fourth century it had again risen to prominence as a military and administrative center for the eastern part of the Roman empire. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, Sep. 15, 2018]

In 325 A.D,, following decades of tense and heated theological debate, the emperor Constantine convened a meeting of bishops in Nicaea to decide upon the central religious debates of the day. Constantine, like other Roman emperors and administrators, was a strong believer in the principles of unity and uniformity. Theological disagreements about the nature of the relationship between Jesus and God the Father had already bubbled into public controversy in the Egyptian city of Alexandria, and Constantine wanted to put an end to the discord, which he saw as fractious and divisive. There had been Church councils before Nicaea, but this was the first that endeavored to reach a consensus by involving global representatives. According to the Christian historian Sozomen, Constantine had Hosius of Cordoba (in Spain) invite the “most eminent men of the churches in every country.”

The Council of Nicaea gave us the Roman version of Christianity rather the Nestorian. The most important decision was the rejection of Arius’s arguments and the adoption of Nicene creed: the assertions that Christ’s divinity, the Virgin Birth and the Holy Trinity were truths and the denial of Christ’s divinity was a heresy. This became the basis of all church doctrine from that time forward. Anyone who departed from the creed was branded a heretic.

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “The first of the ecumenical councils held at Nicea in 325 A.D. has ever aroused the interest of historians and theologians alike. Not only did it establish the precedent for conciliar authority in the Church, but it also introduced the mixed blessing of imperial patronage and control. The bishops who attended did so at imperial command and expense, and its decrees were enforced with imperial assistance. Despite the evils attendant upon this precedent, the council's great importance lay in its decrees against Arianism, the first of the great heresies, an aberation of the Gospel which cut out the very heart of Christianity. Since indeed this heresy reappears among us in subtler forms in every generation, we do well to reconsider the actions of our Fathers who first met this foe and expelled it from the Church. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu]

See Separate Article: COUNCIL OF NICAEA IN A.D. africame.factsanddetails.com

Council of Constantinople (A.D. 381)

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “In 379 Theodosius came to the throne in the East. He was a strong supporter of the Nicene formula, influenced perhaps by a court chaplain, just as Hosius had influenced Constantine. Theodosius is famous forhis edicts declaring Christianity to be the only religion permitted in the empire. (380 AD) "It is our pleasure that all nations governed by our clemency should steadfastly adhere to the religion taught by St. Peter to the Romans, which faithful tradition has preserved, and which is now professed by the Pontiff, Damasus, and by Peter, Bishop of Alexandria.") [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“As the year 380 dawned, the situation of the Church in Constantinople was somewhat confused. The Bishop was an Arian named Demophilus, and most of the Christians were Arians. Theodosius deposed Demophilus, the bishop, and appointed Gregory of Nazianzus to take his place. Meanwhile a certain Maximus the Cynic arrived in Constantinople. He had spent a lawless youth, and had the effrontery to pass off his scars from civil punishments as badges of persecution for the Faith. Maximus had the backing of the Bishop of Alexandria, who wanted to see a creature of his own making as bishop in Constantinople. By intrigue and stealth, Maximus managed to get some bishops together, break into the church at night, and initiate the consecration-proceedings. Soldiers who had been forewarned stopped the proceedings in time. Gregory's position was saved for the time, but the incident was a great shock to him, as he had trusted Maximus implicitly, and it undermined his confidence in his ability to deal with so worldly a position as bishop. =

“There was also confusion in Antioch. After Nicea, most of the Antiochenes supported the Arian cause, but there was always an "orthodox" minority which upheld the Nicene faith. As time went on, however, the Arian group opted for the Nicene position, so that they too were orthodox. The leader of the first group was Paulinus of the second group Meletius. There were thus two warring factions, each holding to the same faith, but the minority under Paulinus always charged the majority with a tainted background and with insincerity. Finally it was Weed that the followers of the bishop who died first would adhere to the other bishop. = “Two important heresies were the occasion for the second ecumenical council. The first was Macedonianism, derived from its author, Macedonius, a bishop of Constantinople. He was something of an unpleasant chap who was supported on his throne by the favor of the government. On one occasion the soldiers had to hew a way through the crowd with their swords to enable him to make progress to the altar. Later on when he removed the relics of Constantine the Great from the church a tumult arose which resulted in a great deal of slaughter. Finally in 360 he was deposed. His special heresy was the belief that the Holy Spirit was inferior to the Son in the same way as the Arians believed the Son was inferior to the Father. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“The second heresy was Apollinarianism. Just as Ariansim represented one extreme, so Apollinarius represented the other. Given the "homoousios" as his pretext, Apollinarius went on to affirm the deity of Christ in such a way as to exclude his complete humanity. The pendulum had swung in the opposite direction. The heresy at Nicea was, "Jesus Christ is only a man." The heresy at Constantinople was, "Jesus Christ is only God." Naturally Apollinarius was a staunch supporter of the Nicene Creed, and as such he had the support and good-will of Athanasius. After Athanasius' death in 373 AD, the opponents of Apollinarius came into open. It was these two heresies, in addition to the continuing vexations of the Arians, which called forth the second ecumenical council.” =

Proceedings Of The Council of Constantinople (A.D. 381)

First Council of Constantinople

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “The 150 who attended were all Eastern ors. In spite of his dubious hold on his See, Meletius of Antioch became president of the Council. The first item of business was to declare Maximus the Cynic an imposter and Gregory the rightful bishop of Constantinople. At this point Meletius died, and Gregory, as bishop of Constantinople, became the obvious choice for president. The Antiochenes, you will recall, had promised to follow the bishop who outlived his opponent. The Heletian faction refused to hold to this promises and they elected Flavian as their bishop. The majority of the council Fathers agreed to this procedure, but Gregory was opposed to it. He refused to accept the councils ruling. In this awkward position of being opposed to the decision of the council, Gregory took the extreme stop of resigning both his presidency and his bishopric. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“The next business was to elect the third president of the council and the way in which this was done throws a very interesting light on the customs of the times. About this time a praetor of Constantinople, Nectarius, was about to take a journey to Tarsus. He called upon the bishop of Tarsus who was present at the council, to see whether he could take any letters home for him. Diodore, the bishop of Tarsus, noticed the stately aristocratic features of Nectarius, and it occurred to him that this was just the kind of man who would make a good president for the council. He added his name to the list of possible candidates being submitted to Theodosius for approval. As it turned out, Nectarius was the only name which appealed to Theodosius, and the appointment was pressed upon him. Like most laymen of the time, he had not yet been baptized. He was therefore rushed through baptisms consecration to the bishopric of Constantinople, and election to the presidency of the second ecumenical council. When all these details were at last settled, the council was able at last to get down to business. =

“The council pronounced the Hacedonians heretical. The rest of its decisions can best be summarized by glancing at the seven canons of the Council. Although only.the-first four have been considered authentic by the West, it seems that the last three were passed at a second session hold sometime in 382 A.D. = 1) Reaffirmed the "Faith of the 318 at Nicea" without specifying the exact creed. It also anathematized the Macedonians and Apollinarians. 2) The second canon dealt with organization. Its main intent was to prevent bishops from interfering with affairs outside their proper jurisdiction. It named the several ecclesiastical areas which were to be considered distinct and separate. 3) "The Bishop of Constantinople shall have the prerogative of honor after the Bishop of Rome, because Constantinople is the new Rome." The implication of this canon was that Rome itself has primacy only because it was the original capital of the empire. This canon has never been accepted by the Church of Rome. 4) the Cynic never was and is not now a bishop. Those who were ordained by him are in no order whatsoever. All of his actions are declared to be invalid." 5) Recognized as true Christians all in Antioch who receive the Nicene faith, regardless of the bishop they follow. 6) Dealt with accusations against priests and bishops of false doctrine. No heretics or excommunicated persons were allowed to bring charges. All charges must first be brought before the bishop of the place. If he cannot settle it, recourse may be had to a greater synod. Accusers must be prepared to submit to an equal penalty if they are found to be guilty of slander. The judgment of the synod was final, from which there was to be no appeal. 7) Concerning the validity of schismatic baptisms; schismatic validity depended upon the faith into which the candidate was baptized. If he accepted the full Trinitarian doctrine it was considered valid. (NB - a reminder that the external form of baptism was not as important as the actual faith into which the candidate was being baptized.) =

“The Church-at-large was slow in recognizing the authority of the council. The next general council, that of Ephesus in 431, does not mention Constantinople at all, and there were many in the East who later spoke of only two great councils, that of Nicea and Ephesus. The triumph of Constantinople (I) did not really come until the 4th general council at Chalcedon. Not until the 6th century was it acknowledged as ecumenical by the West, and this acknowledgement included only the creed not the canons. =

Council of Ephesus in 431

The Council of Ephesus in 431 was called in part to address the policies of the Nestorians and address the issue of whether Christ was dualist (human and divine) or singular (two in one). Nestorian beliefs lost out. At the Council of Ephesus several sects were forced to split from the Christian church. Afterwards the Nestorians were persecuted and exiled. Nestorius was banished to Egypt, where he died in exile. The Nestorians were formally removed from the Orthodox-Catholic church after the Muslim conquests in the 7th century.

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “The period between the second and third general council with significant but unsettling events for the empire. Rome was sacked by the Visigoths in 410 AD, an event which called forth Augustine's "City of God." Notable Fathers of the Church who flourished during this period include Augustine, Ambrose, Jerome, Chrysostom, and Innocent I of Rome. The immediate occasion for the council was the appearance of two now heresies - Nestorianism and Pelagianism. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“The 3rd Newtonian law says something like this, "To every action there is an equal and opposite reaction." This truth can be demonstrated in the history of the first four ecumenical councils, which tended to swing from extreme to extreme, both in the heresies they combated and in the orthodox solutions they formulated. We have already seen that Arianism overstressed Christ's humanity, and Nicea therefore affirmed His deity. At Constantinople Apollinarius overstressed Christ's deity, and the council affirmed His true humanity. The stage was now set for Nestorianism which was, in a sense, akin to Arianism in that it denied any possible participation between deity and humanity in Christ. Nestorius tended to overstress the separation between God and Man, as had Arius, and so we find ourselves back in the same atmosphere as Nicea. In effect, Nestorius said Christ was composed of two persons, although in appearance there was one. =

“A second heresy, Pelagianism, came from Britain. In effect Pelagius denied original sin and claimed that man was able to save himself. His concern was the same as that of Nestorius - the separation between deity and humanity. For this reason it was said that "the Nestorian Christ was a fitting Savior for the Pelagian man." The most vigorous opponent of Pelagianism was Augustine, who attacked the teaching in his book, "The Spirit And The Letter." =

Council of Ephesus in AD 431

“As was true in the other councils, there were personality factors connected with the theological issues. At this time, Cyril of Alexandria was the redoubtable bishop of that See, and in the case of Maximus the Cynic we have already seen the tendency of Alexandria to discredit Constantinople whenever possible. Nestorius had become bishop of Constantinople. Meanwhile, a number of synods had gathered to condemn Nestorius, and an acrimonius exchange had begun between Cyril and Nestorius. Cyril summoned a council of his own at Alexandria which condemned Nestorius. The views were expressed in a synodical letter, to which Cyril attached twelve famous anathemas, which erred as far on the other side as Nestorius did on his. (That is, whereas Nestorius practically affirmed two persons, Cyril practically affirmed one nature - monophysitism). By this time emperor Theodosius II had taken an interest in the debate, and he called the third ecumenical council for Ephesus in 431 A.D. to settle the issue. One more factor demands mention. Nestorius insisted that Mary bore only the human nature of Christ, not the divine, and he refused to allow her the title, Theotokos, God-bearer. Thus Marian devotion was also something of an issue at this council. =

See Nestorians

Proceedings Of The Council of Ephesus (A.D. 431)

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “The day set for the opening was Whitsunday (June 7th, 431). Few of the bishops were there at the time, but by June 22ad enough had arrived to start. Nestorius protested, because most of his supporters were not yet present. The council began nevertheless, with Cyril as president. A summons was sent to Nestorius who had surrounded himself with bodyguards and refused to come. The council settled down to its business without him. The creed of Nicea was read and approved although Cyril's twelve anathema were received in silence. Nestorius was declared deposed and excommunicated. A letter was sent to the Church at Constantinople appraising it of this action and warning the authorities to secure the properties of the See. Meanwhile Nestorius' followers arrived, led by the notable John of Antioch. They held their own council and proceeded to depose Cyril and his followers. The emperor was appraised of this state of affairs, and he ordered both factions to remain in Ephesus until his commissioner arrived to set things straight. The larger party, that of Cyril, continued to hold meetings, but they discovered that their messages to the emperor were being intercepted by Nestorius' agents. Finally the orthodox party concealed a message in the walking stick of a beggar. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“What happened after this is extremely confusing. On two separate occasions the emperor deposed both Cyril and Nestorius. There was a good deal of intrigue and some violence but ultimately the emperor accepted the decisions of the majority. Nestorius was ordered into a monastery and Cyril was allowed to return to Alexandria as its bishop. The Syrian (Nestorian) bishops felt they had been dealt with unjustly, but ultimately they too accepted the condemnation of Nestorius. Nevertheless, the fires of ill-will had been fanned, and they would break out afresh before long. The tragedy of this council was the fact that theology itself seemed to play a minor role in the proceedings. The struggle was primarliy between Antioch (Constantinople) and Alexandria for primacy. The former was supported by a large number of Syrian bishops, the latter by Rome and North Africa. =

“A number of important results emerged from the council: 1) Cyril was the first to introduce the term "hypostatic union" into Christian theology. 2) For the first time, the Nicene Creed was made normative for the reception of converts into the Church. Each bishop, however, was still permitted to use his own creed to summarize his theology. 3) The council took pains to keep the Bishop of Rome informed of the proceedings. In a long and solicitous letter, the council sought his approval. 4) In this same letter, the Fathers stress the fact that their decisions "are in no point out of agreement with divinely inspired Scripture or with the faith handed down and set forth in the great synod of Holy Fathers (Nicea)." =

Council of Chalcedon in 451

Fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon At the Council of Chalcedon in 451 the second person of the Trinity, the son, was defined by Orthodox Christians as having two natures, divine and human. The Armenians, Egyptian Christians (Copts), Syrian Orthodox Christians (also known as Jacobites) disagreed and believed that Christ has a single nature, consisting of two natures, with his humanity absorbed into his deity, a concept known as Monophysitism. The Nestorians supported the Monophysite view but believed in sharper distinctions between the two natures and emphasized Christ’s humanity. The schism that resulted at Chalcedon stimulated the use of Syriac as an ecclesiastical language. By this time Christian scholars from Alexandria were in the minority and the conservative Greco-Roman Orthodox views prevailed. Gaining strength was a mechanism that would remain a central theme in Christianity: the use of that accusations of heresy to dismiss members or sects with unpopular views.

In 518 Monophysitism was declared heretical by Justin I at the Synod of Constantinople. The Greek-speaking Orthodox churches excommunicated the Copts and Syrians because they didn’t accept the Orthodox belief that Jesus was a true God and perfect man. The decision was later overturned by Emperor Justinian on the urging of his wife Empress Theodora. Monophysites of Syria became known as Jacobites. Early Maronites were strong supporters of the Chalcedon view. Jacobite and Maronite monks battled one another, resulting in hundreds of deaths and the destruction of many monasteries.

See Jacobites

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “The twenty years following Ephesus were largely taken up with the efforts to implement its decisions. A large part of the Church was shocked at the treatment which had been given the Syrians, and another large segment felt that Cyril had erred just as much as Nestorius. A few churches in Persia renounced the council of Ephesus and have been labeled "Nestorian" ever since. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“It was at this time that Eutyches, a monk, propounded the theory that in reality Christ had only one nature, a heresy known as monophysite. It is readily apparent that in this heresy the pendulum has swung to the "deity" side, so emphasizing Christ's Godhead that he denied His manhood. In this respect it was akin to Apollinarianism which had been condemned at Constantinople in 381 AD. Eutyches found natural allies in Alexandria, for Cyril of Alexandria had practically said the same thing in opposition to the Nestorians. At this time the bishop of Alexandria was an unsavory man with an inclination to violence. A certain Eusebius of Dorylaeum denounced Eutyches to the Bishop of Constantinople, Flavian. (This Eusebius was the same man who had earlier denounced Nestorius to the emperor, leading some fathers to castigate him as a "bloodhound of orthodoxy".) The Bishop of Constantinople called a synod which denounced Eutyches as being heretical. =

“Eutyches had a great friend at court, however, in the person of the eunoch Chrysaphius. This functionary persuaded the emperor, Theodosius II, to call a council in Ephesus in 449 to review the matter. This council was chaired by the notorious Dioscorus of Alexandria and packed with his adherents. It was a foregone conclusion that Eutyches would be upheld, and so he was. So violently was Flavian of Constantinople handled that he died a few weeks later. This synod was later given the name "Robber Synod" or latrocinium, as it was said to be conducted by a "gang of robbers." =

“When news of these proceedings reached pope Leo in Rome, he denounced it strongly and demanded an ecumenical council. Leo also wrote a letter to Flavian outlining the pope's views on Christology, a letter which has become famous as the "Tome" of St. Leo, crystallizing for all time the accepted orthodox Christology of the Church. Perhaps very little would have come of the appeal by Leo, had not the emperor died from a fall off his horse. This brought Marcion and Pulcheria to power, both of whom were avowed enemies of the Chrysaphius faction, and therefore friends of the Flavian-Leo group. Marcion immediately called for the council, and the fourth ecumenical council was convoked. =

Proceedings Of The Council of Chalcedon (451 A.D.)

Council of Chalcedon

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “This was the largest gathering of bishops yet with 630 in attendance. All were Eastern except the four papal legates. The pope's legates presided. As in previous councils, the Gospels were placed on a raised seat in front of all as representing the ultimate authority. From the outset the target of the assembly seems to have been Dioscorus, with the memory of the latrocinium and Flavian's death still fresh in the minds of the bishops. Dioscorus together with five other bishops was condemned as holding Eutychian views, and Eutyches himself was condemned. At the councils second session it was decided not to put forward a new creed, but rather to reaffirm that of Nicea and Constantinople. At its third session the council decided to depose Eutyches, whereupon the emperor banished him, and he died three years later. At the 4th session the council affirmed as orthodox the Tome of Leo together with the letters of Cyril, though the latter's anathemas were not included (as being monophysite). At its 5th session the council decided to draw up a statement of belief after all, and a committee of 22 was appointed for the task. Ultimately the famous Chalcedonian Definition was formulated, of which the central core was the famous four adverbs; "after the Incarnation, Christ was in two natures, without mixture, without change, without division, without separation." By this time almost half of the bishops had already left, and only 350 signed the statement. [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“This concluded the strictly doctrinal aspect of the council. Eventually, however 28 canons were passed regulating discipline and organization in the Church. Two of the canons deal with monastic orders, placing the monks under the jurisdiction of the bishops. (Note: There is important history here, since the monks had taken a lively part in the Christological debates. This canon seeks to control them in the future.) No slave was to become a monk without his master's permission. Canon 19 stated that bishops should hold twice yearly synods in every diocese. Also every bishop should have a witness of his financial transactions. Canon 22 forbade the clergy from raiding the bishop's property after his death. Canon 25 said a bishopric should never be kept vacant more than 3 months. Canon 6 ordered that all ordinands should have a definite post in view before ordination was permitted. Canon 14 insisted that lower clergy can marry only orthodox Christian girls. Deaconneses cannot be consecrated under age 40. Other canons forbade clergy to take their suits against clergy into secular courts, but to have recourse to the bishop. The most famous of the canons of Chalcedon is the 28th. It aroused the wrath of Rome because it exalted Constantinople to similar privileges and at the same time suggested that the Roman primacy was due to secular causes. In this it repeated the third canon of Constantinople. When the council passed the 28th canon the papal legates walked out of the sessions. Henceforth Rome always had a rival in the East, and within a few short years Alexandria and Antioch deteriorated to second rate Sees. =

“With Chalcedon, the Christological debates came to an end. This was due, no doubt, as much to the clarity and simplicity of the Definition as to the weariness of the Church with the debate. For four centuries the nature of Christ has been in the forefront of theological discussion. "Theology" in the early Church was synonymous with "Christology." The Church now turned to other issues. In the West, Pelagianism still troubled theologians. In other words, anthropology - the nature of man. In the 9th century we find the great Eucharistic controversies and Predestinarian conflicts. In the 12th century Anselm precipitated discussion on the nature of salvation - soteriology. Luther called the Church to examine its authorities and their nature, in addition to seeking the meaning of grace. In our time the issues are more complex, including the nature of authority, interpretation of Scriptural and the Church's relationship to the world. Thus each generation finds itself confronting new issues, which demand new answers, based on our understanding of the Scriptures. =

Some "Lessons" From The First Four Councils

Carl A. Volz of the Luther Seminary wrote: “1) The crucial issue was soteriological, that is, the touchstone question always was,"How does this teaching (heretical or orthodox) affect my salvation? If Christ was not truly God, is salvation accomplished? If Christ was not truly human, can he suffer and die, or be my substitute? So also today? [Source: Carl A. Volz, professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu =]

“2) The arguments were biblical. All four councils were passionate exercises in biblical interpretation. Indeed, in all four councils the participants sat in rows facing each other (not facing the front of the church) and at the front of the church in the position of the "chair" was an open bible, symbolic of the conviction that all discussion must find its authority there. =

“3) All "heresy" was a truly "orthodox" position taken to extremes. There is truth in all heresies (Arianism, Nestorianism, Apollinarianism, Docetism, Pelagianism, etc.). All arise from an orthodox position taken to extremes to the exclusion of other factors. Heresy was not an imposition from outside the church but arose from within. Gnosticism may be an exception to this. =

“4) Human factors played a significant role: Personalities / Nationalism / Ego / Antioch (Aristotle) vs. Alexandria (Plato) / Jealousies / power struggles =

Councils, Schisms and Branches of Christianity

“5) Concern for truth, or at least a way of expressing the biblical witness so as to safeguard salvation. Affirming the deity of Christ was not merely a matter of one-upmanship at Nicea but a matter of salvation and of biblical testimony. It made a difference to one's understanding of salvation whether Pelagius or Augustine were "correct". And basic to all this is the teaching of the church, the tradition to be passed on to the next generation. Shall we tell our children that salvation is by faith or good works? So these debates, messy as they were, were for the heart of the gospel.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024