EARLY CHRISTIAN MATERIALS

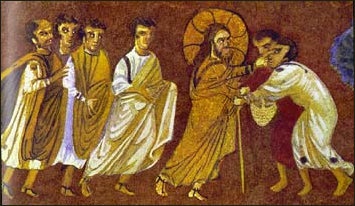

image from the 6th century Rabbula Gospels

Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, told PBS: “A number of archaeological discoveries have cast new light on the writings of the New Testament, expanding our knowledge of the world from which they emerged; a world with which they were also in conversation. For example, here's a famous inscription from the ancient city of Priene (modern Turkey) commemorating the Emperor Augustus and his introduction of the new Roman calendar. It is from the period just before the birth of Jesus. . [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Providence. . . [has sent] us and our descendants a savior, who has put an end to war and established all things. . . .And since the Caesar through his appearance has exceeded the hopes of all former glad tidings, surpassing not only the benefactors who came before him but also leaving no hope that anyone in the future would surpass him, and since for the world the birthday of the god was the beginning of his glad tidings.

“Augustus - who had brought peace and prosperity to a war-weary world - wanted his reign to be viewed as the beginning of a new age. Thus, the celebration of this message became the "glad tidings" or "gospel" of the empire he ruled. As Helmut Koester has noted, it is very likely that the early Christian missionaries were influenced by the imperial propaganda and its use of this word, since the Christian usage of this same term "gospel" for its saving message begins only a few decades after the time of Augustus.

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Early Christian Art oneonta.edu/farberas ; Early Christian Images jesuswalk.com/christian-symbols ; Early Christian and Byzantine Images belmont.edu Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Early Christian Writings: The Apostolic Fathers” by Andrew Louth and Maxwell Staniforth Amazon.com ;

“The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire” by Alan Kreider Amazon.com ;

“The Church and the Roman Empire (301–490): Constantine, Councils, and the Fall of Rome” by Mike Aquilina Amazon.com ;

“The Early Church” by Henry Chadwick (The Penguin History of the Church)

Amazon.com ;

“The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World: by Rodney Stark Amazon.com ;

“The New Testament in Its World: An Introduction to the History, Literature, and Theology of the First Christians” by N. T. Wright and Michael F. Bird Amazon.com ;

“Concise Theology: A Guide to Historic Christian Beliefs” by J. I. Packer Amazon.com ;

“Christian Theology” by Millard J. Erickson Amazon.com ;

“Christian Theology: An Introduction” by McGrath Amazon.com ;

“After Jesus, Before Christianity: A Historical Exploration of the First Two Centuries of Jesus Movements” by Erin Vearncombe, Brandon Scott, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Jesus, the Apostles and the Early Church” by Pope Benedict XVI, Kevin O'Brien, et al. Amazon.com ;

“When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers” by Marcellino D'Ambrosio Amazon.com ;

“When Christians Were Jews: The First Generation” by Paula Fredriksen, Matthew Lloyd Davies, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years” by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Walter Dixon, et al. Amazon.com ;

“A History of Christianity” by Paul Johnson, Wanda McCaddon, et al. Amazon.com

Search for Ancient Christian Manuscripts

Mariane Bonz told PBS: “One of the most basic aspects of recovering the material world of the early Christians is the continuing search for the manuscripts themselves. In the ancient world, these manuscripts came in a variety of forms. Generally produced in the format of a scroll, they were made either from papyrus (a plant) or parchment (animal skins). A scroll was made by gluing or (in the case of parchment) stitching together separate sheets to form a long strip and then winding the strip around a stick. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Sinope Gospels folio of Christ healing the blind

“But scrolls were not very convenient to use, and by the early second century of the common era the codex began to replace the scroll, especially in the production of the writings of the early church. At first these codices were made by folding sheets of papyrus in the middle and sewing them together to form booklets. Gradually, however, the advantages of parchment, such as its durability and the fact that it can be written on both sides, led to its total replacement of papyrus. In fact, leather-bound books made of refined parchment became the state of the publishing art from sometime in the fourth century until the advent of paper in the late Middle Ages.

“Over the course of many years, a number of important manuscripts, both scrolls and codices, have been recovered by scholars and antiquarians. Their recovery is important for New Testament research for a number of reasons and in a variety of ways. For one thing, these discoveries help scholars to determine what were the earliest versions of a given work and what elements may have been added at a later time.

“For example, one of several papyrus codices acquired by the English antiquarian Chester Beatty in the 1930s contained ten letters attributed to the apostle Paul. Conspicuously absent from this particular early manuscript, which was dated to about 200 CE, was any of the so-called Pastoral Epistles (1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus). Accordingly, the discovery of this manuscript helped to confirm what many scholars had already been arguing, namely, that the Pastoral Epistles were not written by Paul himself and that their attribution to the apostle was a somewhat later development within the church.

“An even more important discovery was made by accident in 1934. While sorting through the collection of unpublished papyri belonging to the John Rylands library in Manchester, an Oxford scholar recognized a fragment containing a few lines from the Gospel of John. Paleographers have dated this fragment to the first half of the second century. And since the fragment was found in a small town along the Nile River in Egypt, far away from where the gospel is believed to have been composed originally, it provides strong evidence that the Gospel of John was completed by the beginning of the second century at the latest.

Codex Sinaiticus

Codex Sinaiticus passage from Matthew

Mariane Bonz wrote: “Not all manuscript discoveries or acquisitions have been as simple as those described above, however. Dr. Constantin von Tischendorf's discovery of one of the most important manuscript witnesses to the complete text of the New Testament is a case in point. In 1844 Tischendorf, while a scholar at the University of Leipzig, embarked on a search for biblical manuscripts. His journey took him to the monastery of St. Catherine on Mt. Sinai. During his stay, he noticed a stack of parchment ready for use as kindling in the monastery's oven. After leafing through these discarded leaves of parchment, Tischendorf realized that the monks were about to burn a rare Greek edition of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). Although he could not convince the monks to give him the manuscript, before returning home he was able to convince them that they should find other materials with which to stoke their fires. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“Tischendorf returned to the monastery in 1853 in an unsuccessful attempt to acquire the surviving portions of the manuscript he had saved from the fire nearly ten years before. But it was not until 1859, when Tischendorf returned for a third visit, this time under the patronage of Czar Alexander II of Russia, that Tischendorf's efforts began to meet with success.

“This time the monks granted him permission to examine a large manuscript they kept hidden in a closet. To Tischendorf's amazement and delight, this early fourth-century manuscript, which was in excellent condition, contained not just most of the Old Testament but also all of the New Testament, plus two additional early Christian writings. One of these, the Shepherd of Hermas, had only been known to scholars by its title.

“Even with the patronage of the Czar of Russia, however, the monks were still only willing to allow Tischendorf to make a handwritten copy of the manuscript. It was not until the early decades of the twentieth century that a photographic facsimile of the entire manuscript was finally published. Nevertheless, the years of discovery and negotiation were worth the effort. Today this manuscript, known as codex Sinaiticus, is one of the key textual witnesses on which the current standardized version of the New Testament is based.”

Nag Hammadi Library

The Nag Hammadi writings found near the Nile River in central Egypt in 1945 illustrate the great diversity in the religious speculation and communal piety of early Christian groups. Along with the Dead Sea Scrolls, they helped historians undertstand the religious context out of which the earliest Christian traditions emerged,

Elaine H. Pagels wrote: “There were 52 texts altogether, apparently, unless some of them were burned that we don't know about. And they contain, some of them, secret gospels, such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip. The Gospel of Mary Magdalene is a similar text that was found separately. They also contain conversations between Jesus and his disciples.... All kinds of literature from the early Christian era, a whole discovery of text rather like the New Testament but also very different. [Source:Elaine H. Pagels, The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion Princeton University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Mariane Bonz wrote: “The collection, now known as the Nag Hammadi Library, is of great importance for the understanding of the development of early Christian communities because it presents the social and religious perspectives of groups of Christians who did not prevail in the battles that eventually resulted in the formation of a single, unified church. Their differences with more orthodox Christians covered a wide range of issues, including whether Jesus' death on the cross was either real or relevant, and whether women were among Jesus' true disciples and, therefore, had the authority to teach and to baptize. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Before the emergence of the Nag Hammadi texts, the views expressed in such early Christian writings as the Gospel of Mary, the Apocryphon (secret teaching) of John, and the Dialogue of the Savior were known only from the distorted descriptions found in the writings of their opponents. Since these opponents were famous church leaders such as Irenaeus, Hippolytus, and Tertullian, it is not surprising that their writings were not preserved by the church. Because of the discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library, modern Christians have a much more complete picture of their spiritual family tree.

“The common thread that unites the disparate writings of the Nag Hammadi collection is an emphasis on secret, saving knowledge (gnosis), as well as an other worldly estrangement from human society in general and a desire to withdraw from the corruption of the material world. James Robinson likens the spirit of these writings to the counter-culture movements begun in the 1960s: disinterest in the goods of a consumer society, withdrawal into communes of the like-minded. . . sharing an in-group's knowledge, both of the disaster-course of the [mainstream] culture and of an ideal, radical alternative. . . .This is the real challenge rooted in such materials as the Nag Hammadi library.

Discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library

Mariane Bonz wrote: “As was the case with the Dead Sea Scrolls, the discovery of the literary treasures of Nag Hammadi was largely accidental. Several hundred miles south of Cairo, where the Nile River bends sharply east, beyond the ancient monastery of Pachomius at Chenoboskion, a group of local farmers were digging up the rich soil surrounding the river bed to use as fertilizer for their crops. One of these farmers, Mohammed Ali, happened upon a large storage jar. Hoping that it might contain gold or an equally precious coin hoard, he broke open the jar. Out tumbled twelve large, leather-bound codices. The year was 1945, two years before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Nag Hammadi's Gospel of Philip

Professor Elaine H. Pagels told PBS: “Mohammed Ali going with his brothers on an ordinary errand. They saddled up their camels and they rode out from their village, a small town in the barren stretches of upper Egypt. They took their camels and rode up to a cliff nearby, which is honeycombed with thousands of caves. These caves were used as burial caves in antiquity, thousands of years ago. But they were digging under the cliffs for fertilizer, that is, for bird droppings which fertilized the crops. And Mohammed Ali said he struck something when he was digging underground. And, curious, he kept digging, and he was startled to find a six foot jar sealed. And next to it was buried a corpse. [Source: Elaine H. Pagels, The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion Princeton University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Mohammed Ali said he hesitated to break the jar because he thought there might be a jinn in it. But hope overcame fear; he said he picked up his mattock and smashed the jar, and saw particles of gold fly out of it, much to his delight. But a moment later he realized it was only fragments of papyrus. Inside the jar were 13 volumes, bound in tooled gazelle leather. Thirteen volumes of papyrus text. Now Mohammed Ali could not read these texts. He doesn't read Arabic, which is his own language. And these texts were in some strange archaic language. They were actually Coptic, which is the Egyptian language of 1400 years ago. But he nevertheless put them in his backpack, slung them along and took them home and threw them on the ground in his house near the stove. Later his mother said that she took some of them and threw them into the fire for kindling when she was baking bread. What we didn't know until much later is that these contained some of the most precious texts of the 20th century. That they have uncovered for us a whole new way of seeing the early Christian world.

Bonz wrote: “Mohammed gave one of the books to his brother-in-law Raghib, who eventually sold it to a Cairo museum. Of the remaining eleven books, one was partially burned by Mohammed's wife, and the rest fell into the hands of local merchants. It took over thirty years for the Nag Hammadi codices to be recovered, collected, and edited for the public. They were finally published in English translation in 1978, thanks to the tireless efforts of James M. Robinson of the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity at Claremont Graduate School in California.

“Unfortunately, we know nothing of the history of the group who gathered together this particular collection of writings. We know only what we have been able to learn from the writings themselves. The twelve original codices each contained a number of shorter compositions or tractates, fifty-two in all. They are Coptic copies of writings that were originally composed in Greek. (Coptic is a version of the ancient Egyptian language adapted to the Greek alphabet that was in use in Egypt during the early Christian period.) These writings cover a wide variety of subjects, and they seem to have been composed originally by a number of different authors, at different times, and in a variety of locations.

Early Christian Inscriptions

Christain inscription

Mariane Bonz wrote: ““In antiquity, inscriptions carved in marble or stone were the most effective means that government documents could be publicized to a wide public audience. In fact, inscriptions served as the recording device for nearly every phase of civic life. Anything and everything from imperial decrees, to the recording of holders of local public office, to the public recognition of generous civic benefactors, to the honoring of athletes was made known through the display of professionally carved inscriptions in prominent public places. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“Because of the virtually indestructible nature of inscriptions, many of them have survived the intervening centuries. Already by the late nineteenth century many of these inscriptions had been found and recorded by scholars and interested travelers, particularly those journeying through modern Greece, Turkey, and Syria. Either directly or indirectly, many of these inscriptions have shed new light on our understanding of the world in which the New Testament was written, and they have sometimes helped to answer questions posed by the writings themselves.

“In 1905, a doctoral student in Paris was sorting through a mass of inscriptions that had been recorded and collected from the Greek city of Delphi. He happened to notice that four separate fragments, if joined together, formed the nucleus of an imperial letter. The letter turned out to be a rescript from the emperor Claudius (41-54 CE) to a man by the name of Gallio, the proconsul of the province of Achaea in south central Greece. Since this inscription fixes Gallio's tenure in office to the year 52, and since the Book of Acts mentions the proconsul by name in connection with Paul's stay in Corinth, many New Testament scholars now use this inscription to date an important phase of Paul's missionary journey.

Existence of Godfearers

Bonz wrote: “But inscriptions need not refer to actual incidents in the New Testament in order to provide valuable information for historians of the New Testament world. In fact, inscriptions that shed light on unfamiliar terms or social structures mentioned only in passing by New Testament writers can be of far more value to the historian. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Aphrodisias Godfearer inscription

“For example, in speaking of Paul's missionary visits to local synagogues in the provincial cities, Acts repeatedly implies the existence of a group of pious gentiles who regularly attended the synagogue services and were known as "Godfearers" (Acts 13:16, 26; 16:14; 17:4, 17; 18:7). Until fairly recently, these references had remained something of a puzzle, because even though the term "Godfearer" had appeared in a number of inscriptions referring to a particular individual, there was no firm evidence of groups of "Godfearers."

“All that changed dramatically with a chance discovery in 1976. When a team of archaeologists from New York University was excavating an outlying area of the ancient city of Aphrodisias in south central Turkey, they uncovered two very interesting Jewish donor inscriptions. One of these inscriptions, dated to the early third century, lists a group of donors, all with Jewish names, to which was added the phrase, "and all those who are Godfearers." Following this phrase is another long list of donors, all of whom have gentile names.

“Unfortunately, the top of the inscription is broken off, so that we do not know exactly for what sort of benefaction these people were being honored. Nevertheless, scholars now have evidence that large numbers of gentiles were strongly attracted to and did participate in the worship and community life of the synagogues, even though they did not fully convert to Judaism. Furthermore, Acts is probably correct in suggesting that such groups might have been especially receptive to the message brought by early Christian missionaries.

Early Christian Art

Philip M. Soergel wrote: Some of the earliest Christian art comes from Dura-Europos, a Roman garrison town on the Euphrates River in modern Iraq. The wall paintings that were found made art historians rethink their notions about the retreat from naturalism in the late Roman Empire that had hitherto been associated with the rise of Christianity. There was a Jewish synagogue with scenes from the Old Testament. These came as a surprise, for Judaism took the Second Commandment banning "graven images" very seriously, as did early Christianity, but by the start of third century A.D., the veto for both religions had broken down. There was a Christian "house church". Before Christianity became a legal religion, Christian congregations met in ordinary houses which were adapted for worship; we know that there were at least forty such "house churches A.D. At one end of the baptistery room in the Dura "house church," set in a vaulted niche, there was a font shaped like a sarcophagus, and on the back wall of the niche was a painting showing Christ as the Good Shepherd, carrying a sheep on his shoulders, and beside him, Adam and Eve. This was clearly an example of wall painting as a mode of instruction: Adam and Eve represented the old Adam who sinned, and Christ, the new Adam, redeemed the victims of original sin. [Source:Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

The synagogue paintings were also art serving to instruct, and since they date before the "house church" was built, the Christians probably borrowed the idea of using art for religious education from the Jews. One synagogue painting shows the prophet Samuel anointing David as the future king of Israel while his six older brothers look on. Samuel towers over David and his brothers who are all the same height, though David's status is marked by the purple toga that he wears like a Roman emperor. The figures face the onlooker, fixing him with an intense gaze, and they seem to float in air. This frontality and weightlessness is even more pronounced in the sacrificial scenes that were painted and carved in the Temple of the Palmyrene Gods in Dura. By contrast, the art in the Christian baptistery has not quite abandoned the classical tradition. The "Christ the Good Shepherd" figure recalls a classical type; among the archaic sculpture found on the Athenian Acropolis there is an example, the dedication of Rhonbos showing a man carrying a lamb on his shoulders. The Dura finds make it clear that the features associated with early medieval art — two-dimensional, weightless figures in frontal poses — developed independently of Christianity, and that their inspiration came from the Middle East.

Roman-era Adam and Eve

Apart from the "house church" at Dura-Europos, examples of early Christian art come from the catacombs: underground cemeteries hewn from the rock-like tunnels for mines. The cata-combs were not solely Christian — the Jewish catacombs in Rome antedate the Christian ones — nor are they only in Rome: there are also catacombs in Naples, Syracuse in Sicily, and Alexandria. Christians, like Jews, did not cremate their dead, which was the prevailing custom in the pagan world until the late A.D., and the catacombs provided burial places that a Christian of modest means could afford. Most of the catacomb burials ar A.D. when Christianity was made legal by the so-called "Edict of Milan," and so the old romantic notion of persecuted Christian believers gathering secretly for worship in the catacombs must be abandoned. The dead were placed in niches (loculi) stacked one above the other like shelves lining the underground galleries, and in various places small rooms (cubicula) cut out of the rock served as funerary chapels. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

The paintings in the loculi and particularly in the cubicula are our earliest examples of Christian art. The style is similar to contemporary pagan art, though there is a charming naivete about the pictures. They are narrative art but they have an educational purpose: they give instruction in the Christian faith. Christ is usually shown either as a teacher or as the Good Shepherd, caring for his flock of sheep. In the early drawings he is depicted as a young man and beardless; he might pass for a young pagan god. The figure of Christ as a mature man with a full beard developed only later in Constantinople in the fifth century, and perhaps it reflects the impression made by Phidias' great gold-and-ivory statue of Zeus at Olympia when it was taken to Constantinople after the temple was closed by imperial decree in 391. The catacomb paintings were executed by journeymen painters who worked quickly in poor light, surrounded by decaying corpses, and they are not great art. They borrow heavily from the classical tradition. Yet their general aim was instruction in Christian piety, and though occasionally figures from classical mythology appear if they can be linked in some way with Christian teaching, the subjects are usually stories that convey a message from the Old and New Testaments.

Roman Art in the Ancient Christian Era

Bonz wrote:“Not all of the relevant information of the ancient world was recorded in inscriptions. In fact, because the literacy rate was so low, visual imagery was a much more effective means of popular communication. One important example of Roman imperial art specifically created for conveying political messages to the citizens of Rome and the inhabitants of the empire was the erection and decoration of massive triumphal arches. These arches were erected at government expense at various locations throughout the empire, but especially in Rome itself. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Still standing today in the city of Rome is the magnificently carved marble arch that was erected to commemorate the emperor Titus's victory over the Jews in 70 CE. The monument, which was completed shortly after Titus's death in 81, illustrates and celebrates the victory of Rome over Jerusalem, and, by implication, the favor bestowed on the Roman leader by the goddess Victoria.

“In Book 7 of the Jewish War , the Jewish historian Josephus describes in great detail the enormous victory parade held in Rome immediately after the war. A close comparison of the scenes carved on the arch and Josephus's literary description reveals that a significant part of the relief decoration carved on the arch of Titus is a visual narration of that victory parade. For example, one panel features part of a procession in which spoils from the Jerusalem Temple are conveyed on a float. The objects displayed are cult objects, such as the shewbread table. Also carved in intricate detail is a magnificent reproduction of a seven-armed candelabrum or menorah.

“As one would perhaps expect, other panels focus on Titus himself. One scene depicts his role in the triumphal procession. He is pictured in a magnificently decorated chariot, drawn by four horses. Above his head the goddess Victoria herself holds a golden crown. But the scene that is accorded the greatest prominence records an event that took place eleven years later. The dead emperor is portrayed as being carried off to heaven on the wings of an eagle. Viewed as a unified visual message, therefore, the arch celebrates Titus as the hero of the Jewish war, who eventually becomes a god because of his extraordinary service in maintaining the peace of the empire.

“The fortunate survival of the arch of Titus adds an important dimension to our understanding of the outcome of the Jewish war and what it meant to the various participants. The event that was seen by Palestinian Jews as an unbelievable tragedy, and by some early Christians as God's judgment against a sinful people, was viewed by many pagans as further proof of Rome's divine mandate to rule the world on behalf of the gods.

“Generally speaking, Roman emperors had extensive funds by which they could promote the political and religious messages of their reigns through monumental art. But they also had the rather simple but extremely effective medium of imperial coinage. By this means, they could reach as great a proportion of people in their everyday lives as can be reached today through the modern medium of television advertising.

“"Give to Caesar what belongs to Caesar," says Jesus as reported in the gospels (Mark 12:17; Matt 22:21; Luke 20:25). These words are prompted when one of the Pharisees produces a coin with a depiction of the emperor's head on one of its faces. The point of Jesus' remark is that no matter how powerful the emperor may be in the political realm, his influence does not extend to the spiritual realm.

Healing of a Bleeding Woman

“In this and other narrative scenes, the New Testament gospels reflect a keen awareness that the message of the good news regarding Jesus must compete in a world where other, very different messages easily circulate through every level of daily life. Imperial coins not only portrayed the emperor's face but quite often they advertised his accomplishments. Two of the most common messages that Roman coins emphasized regarding the emperors were their accomplishments in battle that maintained the peace of the empire and their generous benefactions that enhanced the material well being of its subjects.”

Popular Early Christian Religious Art

Bonz wrote:“Another way in which material remains can increase our understanding of the world in which the early Christian message was spread is by giving voice to other messages of hope and salvation that seem to have held appeal to the ordinary inhabitants of the Greco-Roman world. The situation in the provincial city of Philippi is a case in point. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“According to the Book of Acts, Paul began his major missionary journey in Philippi (Acts 16:11-40). Furthermore, we have his letter to the Philippians in which he indicates a special affection for the Christian community there. Yet, if we had to depend only on the details of these and later Christian writings, we would know very little about what aspects of the Christian message may have appealed most to the pious pagans of this small agricultural city. But thanks to the survival of some rather unusual material evidence, we do know something about the piety of ordinary people in this particular part of the world, at this particular time.

“Located in northeastern Greece, Philippi was a Roman colony nestled along the Via Egnatia, the principal highway leading from Rome to the Aegean coast. Even today, visitors to the site can see the remains of its forum, with its once-splendid fountains, its well-appointed library and civic offices, and its monumental temples honoring the patron goddess of the city and the imperial family.

“Beyond the forum to the south was a thriving commercial center and beyond that, the fertile fields of the Datos plain. But on the northern side of the great Roman highway looms a steep outcropping of rocks that leads to the higher elevations of the Pangaion Mountain. Scattered over this lonely stretch of rock is an incredibly rich profusion of rather crudely carved religious representations, graphic and poignant witness to the simple piety of ordinary people.

“These rock carvings are the products of local artists of minimal skill, doubtless commissioned by people with limited financial resources. The majority of them seem to have been commissioned as an act of piety and gratitude for some gift of protection, healing, or rescue that the god or goddess is credited with having performed on the suppliant's behalf.

“To date one hundred and eighty-seven reliefs have been identified, forming a kind of extended open-air sanctuary. The goddess Diana (the Roman counterpart to the Greek goddess Artemis), in her role as huntress is featured most prominently. In fact, there are over ninety separate representations of her in various hunting poses. This is perhaps not surprising in an area so predominantly rural in character. This evidence of popular concern for the risks and rewards of the hunter is further emphasized by the presence among these same rocks of a roughly carved sanctuary to Sylvanus, a Roman god of the woodlands.

“Although these deities of the woods and the hunt predominate the rocky landscape above the city of Philippi, a variety of other deities are also represented, including the Phrygian mother goddess Cybele and the Egyptian goddess Isis. Although Egyptian in origin, Isis became extremely popular in the Roman empire as a compassionate goddess who could heal, protect, and possibly grant her worshippers a better life in the next world.

“Higher up the mountain, Isis had her own temple and small sanctuary complex. But she is also honored among the rock carvings. In one of the few inscriptions accompanying a relief, Isis is honored as the Queen of Heaven, a frequently repeated title for this goddess. Other votive offerings found nearby attest to her mercy and her healing powers.

“What all of these deities who are honored in this desolate rocky outcropping have in common is that they extend concern and protection to ordinary people and to the occupations and preoccupations of their everyday lives. Paul appears to have understood this need of ordinary Philippians. And in his letter, he sought to address their longings by encouraging prayer and redirecting their supplications to the one God of Christian faith: "Do not worry about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be known to God" (Phil 4:6).”

Early Christian Catacomb Art

Bonz wrote:“The extensive and almost continuous exploration of early Christian catacombs has revealed a rich, albeit largely hidden world of early Christian art and imagery. As Margaret Miles wisely remarked, one must go to the catacombs for detailed information about the images that early Christians associated with their faith. [Source: Mariane Bonz, managing editor of Harvard Theological Review, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Although for some Christians they have been the object of religious pilgrimage since their very creation, it was not until the fifteenth century that scholars began visiting the Roman catacombs in the spirit of historical investigation. In 1475 the founder of the Roman Academy writes of discovering walls covered with paintings of biblical scenes on a visit to the San Callisto catacomb, located on the Appian Way. In the late sixteenth century, excavation of an area on the northern outskirts of the city led to another major underground grave site. Before the end of that century, the first of several Jewish catacombs had also been discovered in Rome. And the discovery of more catacombs has continued almost to the present time.

Catacomb of Domitilla

“How did the popular piety of the Christians of the third and fourth centuries express itself in the wall paintings surrounding these Christian graves? First, human figures, generally representations of the deceased, are depicted in a highly stylized manner. Typically, they stand with arms raised and large eyes also raised upward in a stereotypical attitude of early Christian prayer. In addition to these pious depictions of the deceased, early Christian tombs are also frequently decorated with religious symbols such as crosses and fish. A third subject typically portrayed in early Christian tomb art are a rich variety of scenes from biblical stories. Here a certain progression or development can be seen in the type of biblical subjects depicted in fourth-century art as compared with the subjects most often portrayed at third-century grave sites.

“In the third century, the biblical scenes are invariably taken from the stories of the Old Testament. Probably because of the persecutions that began in the middle of the third century and in which a number of Christians died, the artists of the third century especially favor stories of divine deliverance, such as Lot's escape from Sodom, Samson's slaying of the lion, and the many inspiring stories featuring Moses.

“Why the apparent reticence of third-century Christian artists regarding specifically New Testament themes? Some interpreters have suggested that it was because even in the third century New Testament writings had not achieved the full status of scripture, and the collected books of the Greek version of the Old Testament still remained the official Bible of the Christian churches. Others suggest a more practical answer: third-century Christians may have feared the desecration of the graves of their loved ones, if they should be marked as Christian in so conspicuous a manner. Whatever the reason, with the arrival of the Peace of the Church in the early fourth century, catacomb art became enriched by the addition of a number of specifically Christian biblical scenes, including illustrations of the healing miracles narrated in the gospels and depictions of the Last Supper.

“But by far the most commonly portrayed subject was Christ himself in the role of the Good Shepherd. And this phenomenon provides dramatic evidence that in the popular mind Christ had come to assume the role of divine protector, nurturer, and savior — just as the pagan predecessors of these fourth-century Christians had worshipped such protecting, healing, and saving deities as Herakles, Asclepius, Artemis, Mithras, and especially Isis. In the end, the virtues of the many had been found to reside in the One.”

Oxyrhynchus Hymn: Oldest Christian Music

The Oxyrhynchus hymn is the oldest surviving piece of Christian Music. According to smithcreekmusic.com: “Oxyrhynchus was among Egypt's most prominent cities under its Hellenistic and Roman rulers. It was a prosperous regional capital, third city of Egypt, and home town of Athenaeus. Today its name is el-Bahnasa. The town lies roughly 300 km south of the coastal metropolis of Alexandria, or 160 km south-west of Cairo (ancient Memphis). It is situated on the Bahr Yusuf, the branch of the Nile that terminates in Lake Moeris and the Fayum oasis. Oxyrhynchus, or Oxyrhynchon polis, means ‘City of the Sharp-nosed Fish’. [Source: smithcreekmusic.com]

“We know more about Oxyrhynchus as a functioning town, and about its people as living individuals, than we do about many more glamorous ruins because of the town dumps. These remained intact right up to the late nineteenth century, as they were not considered likely sites for treasure-hunters. They have yielded the largest collection of ancient papyrus ever discovered. Among these papyrus fragments is the earliest known Christian hymn, dating from the second or third century AD.”

Christain catacomb painting Christ the Teacher

Here are the words of the hymn in the original Greek, together with the English translation:

-ytaneo sigato,

med' astra phasesphora lampesthon

potamon rhothion pasai

hymnounton d'hemon patera k'hyion k'hagion pneuma

pasai dynameis epiphounounton Amen

kratos, ainos aei kai doxa theoi Empire,

doteri monoi panton agathon.

Let it be silent,

Let the Luminous stars not shine,

Let the winds and all the noisy rivers died down;

And as we hymn the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit,

Amen Let all the powers add "Amen Amen"

praise always, and glory to God,

Amen Amen The sole giver of good things, Amen Amen.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Aphrodisias Godfearer inscription from Oxford University

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024