ZOROASTRIANISM

Faravahar Zoroastrianism is one of the most ancient religions still practiced today. Founded by a religious leader named Zoroaster, it preceded Judaism and Christianity, has links with Hinduism and may date back to before 6000 B.C. Zoroastrianism is believed to have developed among tribal-pastoral people living in the mountain ranges of the Hindu Kush and Seristan, a territory shared by Iran and Afghanistan. From northeast Iran it spread through the Persian Achaemenid Empire beginning around the 6th century B.C.

Zoroastrianism is credited with helping to unify various tribes that lived in Persia in the 6th century B.C. into the Persians. At its height Zoroastrianism was the predominate religion of people in Persia and Asia Minor and parts of Central Asia and the Middle East. After the conquest of Alexander the Great, Greek and Semitic elements were added to the religion. In A.D. 226, it became the state religion of the Persian Sassanian Empire, which spread as far as east as India and as far west as Egypt. The most famous Zoroastrians are perhaps the Three Wise men who visited the infant Jesus.

Zoroastrianism remained a major religion until the Arab invasion in the 7th century when most Persians converted to Islam. Under Muslim rule, Zoroastrians were persecuted and subjected to forced conversion. During this period many emigrated to India, where they became known as the Parsis. Some also moved to China but that community was suppressed in the 11th century.

The Zoroastrians that remained in Iran endured severe poverty and discrimination. By the 13th century they had disappeared from the historical record. It wasn’t until European began exploring Iran in the 17th century that the Zoroastrians were rediscovered.

Zoroastrian Numbers

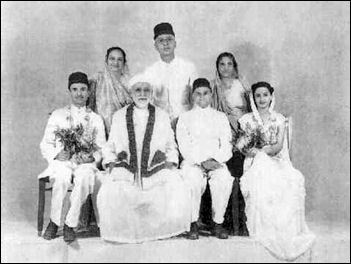

Parsi wedding portrait There are about 120,000 to 150,000 practitioners of Zoroastrianism (2009), with more than half in India and less than half in Iran. This is around half the number of a few decades ago. A third are over 60. Zoroastrians used to number in the millions but have suffered as a result of persecution, conversion to other religions and a low population growth rate. They have had a particularly hard time in Iran, where there could be as few as 30,000 left.

About 70,000 practitioners of Zoroastrianism live in India, where they are known as Parsis. About 70 percent of them live in Bombay. They have also settled in recent times in all the major cities and towns in India. They are lighter skinned than other Indians and they view themselves as a separate ethnic group as well as member of a religion. There may be some Parsis in Pakistan. The word Parsi is derived from “Pars” or Persian.

In the 1990s were around 135,000 practitioners of Zoroastrianism living in Iran. They made up less than 0.2 percent of the population. It is not clear how many remain today. They live in small communities in Yad, Kerman and Tehran. In Iran Zoroastrians are not known as Parsis. They are known as Gabar, Gabr, Guebre and Zardoshti. Many Muslim Iranians regard them as infidels.

See Parsis, India

Zoroastrianism and Other Religions

Zoroastrian Tomb Zoroastrianism is regarded as the first religion to teach monotheism, the belief in one supreme god, a cornerstone belief in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Judaism is said to have been influenced by Zoroastrianism when the Jews were in exile in Babylon when it was under the rule of the Persians. These influences were passed on to Christianity and Islam.

Many of the personalities and concepts in Judaism and Christianity evolved from Zoroastrianism, The Three Wise Men that visited the new-born Christ in Bethlehem and many of the Persian kings mentioned in the Old Testament were Zoroastrians. The concepts of Satan, angels, monotheism, Messiahs, the final judgment, the Resurrection, the Apocalypse, Heaven and Hell were all introduced by Zoroastrianism.

Zoroastrianism is also regarded as the first universal religion, meaning that it wasn’t a tribal faith like Judaism or the Egyptian religion, which were originally associated with one tribe, group of people or kingdom. From its inception Zoroastrianism aimed to convert people of all backgrounds and tribes. It welcomed outsiders and said that salvation was theirs if they embraced the religion. It was tolerant of other religions in that people were judged on the basis of their deeds not their faith.

Zoroaster

Little is known about the real Zoroaster other than that he probably lived in northeast Iran sometime between the 15th century and the 6th century B.C. It is believed that he was a priest who was given messages from God in a series of visions sort of like Mohammed was. What are believed to be his words are included in the Gathas, the oldest writings in Zoroastrianism. Zoroaster is believed to have come from a region between the Hindu Kush and Seistan. Some historians believe that he may have lived in Margiana in present-day Turkmenistan.

According to religious texts, the Prophet Zoroaster (known as Zarathustra in Iran) was born to a 15-year-old virgin around the 7th century B.C., when it was believed that all saviors born after him would be born to 15-year-old virgins. When he was fifteen he dedicated his life to religion.

When Zoroastrian was 30 he had a series of revelations and was given instruction by Ahura Mazda (the Zoroastrian God) to found the Zoroastrian religion. He began preaching his faith and converted many people. The religion took off after King Vishtaspa was converted when Zoroaster was around 40.

Like Jesus, Zoroaster resisted temptations, performed miracles and converted new followers with his charismatic sermons. He married the daughter of King Vishtaspa and used the king’s resources to spread the word of religion. He had two sons and a daughter and was supposedly murdered when he was in his seventies.

Zoroastrian temple in Yazd

Zoroastrian Beliefs

Zoroaster taught that there was one supreme god, Ahura Mazda ("Creator of Order and Light"), the god of light and good. He created the universe in six creations. Zoroastrianism teaches that all of the souls of the living and dead today were present at the beginning of the universe and it through them that world is kept in motion. There are beliefs in the power of magic.

Zoroaster taught it was the duty of each individual to help Ahura Mazda by living morally and following the words “good thoughts, good words, good deeds.” Zoroastrians value the “Asha” (the law of God), the concept of spiritual love, and practice loving one’s fellow man. They believe in individual human responsibility and hold in high regard the virtues of truth, purity, simplicity, good thoughts, good words and good deeds. They also believe that the soul and the flesh are united and a messiah-like figure Essiag will save the world.

Zoroastrianism is regarded as a very social religion. It stresses hard work and enjoying oneself. Men have a religious duty to bear children and raise cattle. Asceticism and being a bore are viewed as sins and followers are encouraged to have a "healthy body." During religious holidays Zoroastrians are encouraged to party it up and have a good time. Even so Zoroastrians condemned the use of “haoma”, a potion made with opium, cannabis and ephedra plants.

Contrary to its initial concept of universality, modern Zoroastrianism does not welcome new members and is passed on from generation to generation. This accounts for it shrinking numbers and status as a dying religion.

Zoroastrianism, Evil and Satan

Zoroastrians regard the existence of evil as necessary and that men achieve goodness through battling it. They also view life as struggle between the Ahura Mazada and the devil Ahriman (Prince of Chaos and Darkness) and believe that man has a free will to choose between God and the devil and that Ahura Mazada has given man intelligence to carry out the fight which provides man with the insight that the good life is sometimes hard but the consequences of evil are worse. Ahriman’s power is almost equal to that of Ahura Mazda.

Zoroastrian fire pot The battle between good and evil is also expressed in the conflict between the good spirit Spenta Mainyu and the evil spirit of Angra Mainyu, both offspring of Ahura Mazda. Their battles are sometimes seen as metaphors of the choice between truth and lies. Humans can tip the balance in the favor of good by practicing “good thoughts, good words and good deeds.”

The history the world is seen in terms of conflicts between good and evil that take place over four 3000-year periods. In the first two God and the devil prepare their forces. In the third they fight it out, In the forth the devil is defeated and the existence of evil is completely eliminated and truth and happiness prevail.

There are beliefs in other spiritual beings. Among the most important of these are the seven beneficent immortals, which are beings as well as representations of Ahura Mazda’s virtues such as “best truth” and “immortality.” Zoroastrianism also absorbed some earlier Indo-Iranian gods such as Yazatas. These god generally have responsibilities over the material world. There is also reverence of Fravashis, or spirits of the soul, associated with deceased people that lived particularly virtuous lives.

Zoroastrian Judgement, Heaven and Hell

Zoroastrians believe that individuals are responsible for their own souls and their fate in the afterlife is determined by the good and evil deeds they perform while they are alive. After a person dies the soul remains bound to the earth for three days. On the forth day the soul rise with the sun to the Chinvat Bridge, the Zoroastrian equivalent of a Judgement Day.

For people who have performed mostly bad deeds the bridge narrows to a razor’s edge and they fall into the House of Lies, a place ruled by Ahriman. The Zoroastrian concept of hell was adapted in part from views about places of afterlife punishment for sinners that had been around for a long time in religions in Egypt, Persia, India and other places.

People who have performed mostly good deeds cross the bridge, escorted by an attractive member of the opposite ex, to one of the seven garden-like, heaven-like paradises near the sun. The Persian word “pairi-daeza”, or enclose, is the source of the word paradise. Zoroastrians regard judgement, heaven and hell as metaphorical places that can bring great bliss or pain but are largely incomprehensible to the living.

Fire in Yazd Zoroastrian temple In addition to heaven (Behesht) and hell (Dozakh) Zoroastrians have a place in the middle (Hamestegan), a realm with no joy but only mild suffering. Here they wait in a kind of twilight until resurrection at the end of time. It was not like purgatory in that one could not work one’s way to heaven.

Zoroastrians also have an end of the world scenario ushered in by arrival of a final Messiah. When this occurs all souls are resurrected and the mountains turn to river of molten metal. During a final judgment everyone is immersed in the molten rivers. For the pure it feels like a warm bath. For wicked they endure horrific suffering as their skin and flesh melts off their bones. In early Zoroastrian text the souls of the wicked were destroyed forever. In later texts, the wicked were thus purified and allowed to dwell in paradise.

Zoroastrianism, the Soul and Fire

Zoroastrians believe in the immortality of the soul. After death they believe that the soul stays near the body for three days, during which time ceremonies for the dead are performed.

Zoroastrians believed that a soul has nine parts: three physical ones (1, bodily matter and sensation, 2, the physical frame and nervous system, 3, skeleton and muscles); three subtly material ones (4, life energy, 5, the astral body, 6, ethereal substance), and three spiritual ones (7, the link between sensation and soul, 8, inner soul, 9, divine spark).

During life the nine elements work together on three “planes” to keep a human being going. After death the elements go their separate ways, the first six ultimately dissolve, leaving behind the last three, which unite and become immortal.

Zoroastrians have been called fire worshipers but that is not really the case. They don’t worship fire but they revere it as a symbol of purity, truth, divine grace and law and as a representation of their God, Ahura Mazda., and his splendor. Zoroaster saw divinity in flames and called it Atar. Prayer is often performed in front of fires. There is always a sacred fire attended by priests burning somewhere and keeping this fire alive is very important. Before some rituals the fire is crowned. The tradition may date back to Aryans — the source of the Indo-European Persian language — who used fires in a number of their rituals.

Fire is the main symbol of Zoroastrianism and is treasured for its warmth and use in cooking meat. Priests make offerings and individuals recite prayers around sacred fires. Every ritual and ceremony requires the presence of a sacred fire. Offerings of frankincense and sandalwood are made to the fire at least five times a day by ordained priests who wear a veil that covers their lower face to keep his breath frm polluting the fire. Non-Zoroastrians are not allowed to set eyes on the sacred fires.

Zoroastrian Fire Temples, Sacred Books and Priests

Parsi jashan ceremony Zoroastrian fire temples (Atashkadeh) are central to the Zoroastrian faith. A sacred fire is ritually consecrated and installed and is kept going in a brazier in the fire temple. Keeping the fire alive is very important. One fire in a desert shrine near Yazd has been kept going for 1,500 years, and has been moved at least four times. A smaller ritual fire is kept in every Zoroastrian home.

The “pure place” where high rituals are performed consists of a small rectangular-shaped piece of ground surrounded by prayers intended to ward of evil. It is purified with water and prayers. Those that attend are expected to be spiritually and physically clean. Non-Zoroastrians are often not allowed to enter a temple because they do not carry out the prescribed cleaning and purification.

There are about 50 fire temples in Bombay, which only Parsis are allowed to attend. The sites of visions of saints and angels are made into shrines The sacred fire of Azar Gushnasp is said to sit beside a bottomless lake.

The sacred Zoroastrian texts are fragmentary. These include the “Avesta” , dating back to the 4th and 6th centuries B.C. and attributed to Zoroaster himself. It is written in the Zoroastrian liturgical language of Avestan. This is supplemented by later Pahlavi texts written in Middle Persian and dated to around the A.D. 9th century and modern texts from the last 200 years in India and written in Gujarati and English. Avestan is a member of the Indo-European family of languages and is closely related to Sanskrit. It was developed in the A.D. 5th century with the explicit purpose of recording religious material because existing languages were regarded as inadequate for recording sacred words.

The words and teaching of Zoroaster are contained within the 17 hymns of the “Gathas” , which are part of the “Yasna” , Zoroastrian sacred book which has 72 chapters. The texts has connections with the Hindu Rig.” Interpretations of Zoroaster’s teachings vary greatly.

The Zoroastrian community has traditionally been divided into two groups: hereditary priests and the laity. In the old days, magi were priests and scholarly men who kept themselves pure, carried out daily religious duties and nurtured the sacred fire. Zoroaster set down strict rules about how the were supposed live their lives simply and ascetically. Over time they became the object of jokes by non-Zoroastrians. The word “magic” is derived from magi. The three wise when who followed the star to the baby Jesus were magis.

Parsi navjote sitting Today there is hereditary clergy is divided into Dasturs (high priests) and Mobeds. A male descendant of priests up to the 5th generation may take up the profession. There are no monastic orders, nor are their women functionaries. Priests can marry.

Zoroastrian priests have traditionally worn white caps and white robes. Many have long white beards. The process of becoming a priest is long and difficult, involving several purification rituals and memorization of texts. There currently is a shortage of priests. The sons of priests prefer other professions.

Parsi Festivals, Initiation and Life Cycle Events

For Parsis, there are major life cycle ceremonies to celebrate birth, initiation, puberty, marriage, pregnancy and death. Before each of the ceremonies participants purify themselves by confessing their sins and during it they mark their foreheads with ashes from the sacred fire. At birth a child is given “haoma” ,the juice of an intoxicating plant. At age seven a child is initiated into the Zoroastrian religion with a nine-day ceremony that required the recitation of certain prayers in Avestan and the presentation of a ritual cotton shirt and sacred belt of lambs wool and 72 threads.

One of the most important rituals is the “Naojot” ceremony, a Coming of Age ritual in which young Zoroastrians are initiated into their faith and symbolically take on the responsibility of the religion. Naojot is held for both girls and boys when they are around seven. Initiates are ritually given a “sadre” (a sacred vest) and “kasti” (sacred thread with 72 strands) which is tied with three knots and wrapped around the waist three times to symbolize universal fellowship, the chapters of the Yasna and the three rules of Zoroastrianism “good thoughts, good words, good deeds.” Once a child finishes naojot, he or she accepts responsibility for his or her own salivation, religious observations and morality.

The sadre is made of white muslin. It has two halves — a back and front’symbolizing past and future. Near the neckline is a small pocket-like fold. Children are taught from an early age to keep it filled with goodness and righteousness. The kasti made of undyed wool. It is a hollow tube made up of 72 strands ending in several tassels.

Sadeh is a Zoroastrian mid-winter festival honoring the discovery of fire and celebrating its ability to banish the cold and dark. It is celebrated in the depth of winter on a snowy mountain near Cham, a small village in central Iran, by the lighting of giant bonfires fires. Sadeh was the national festival of Persia before the conquest of Islam in the 7th century. In addition to the fires, white-robed priests recite hymns in ancient Persian and children dance to lively music. The celebration climaxes when men and women in white traditional clothes, and carrying torches, light the massive bonfire.

See Iranian Holidays

Zoroastrian Rituals and Religious Observations

Parsi chuna closeup Zoroastrianism is a secretive religion. It is full of ancient rituals, customs and symbols that are thought to be more than 2,500 years old. Some of them have been absorbed into wider Iranian culture.

Zoroastrians pray five times day like Muslims. The prayers involve reciting of a basic credo while untying and retying the kasti. A Zoroastrians must always wear the sadre and kasti. The kastri is tied and untied many times during the day as a prelude to prayers, eating and toilet duties.

Water and purification rituals are important to Zoroastrians. Water makes life possible. People deemed impure are segregated from others. Bodily substances such as saliva, urine, and menstrual blood are regarded as impure. Menstruating women used to be segregated but this customs is falling into disuse in urban areas where there are few places where women can be sent.

Parsis welcome guests with rose water and candy made from crystallized sugar and pistachios. The considered the use of toothpicks a religious rite.

The chief ritual is Yasna, a kind of sacrifice which includes the offering of haoma (the juice of an intoxicating plant), water and milk before the sacred fire to honor Ahura Mazda. The ritual strengthens both god and evil. In the old days the sacrifice of animals was part of the ritual.

Parsi Funerals

Zoroastrians regard death as separation of the immortal soul from the body and view corpses as extremely polluted dwelling places for demons. The dead cannot be cremated, buried or thrown in the sea because those practices would defile the sacred elements of fire, earth and water. According to sacred Zoarastrian texts: “No impure thing can, therefore be thrown upon any one of these elements, because it would spoil the good creation by increasing the power and influence of demons, who take possession of the body as soon as a man dies.

Instead the dead are laid in circular walled enclosures called Towers of Silence (“dokma” or sometimes “dakma”) to be devoured by vultures and become mummified in the desert sun. “Stripping the flesh” is regarded as a clean method to dispose of bodies. According to a Zoroastrian text: “There shall they deposit his lidless body for two night, or three nights, or a month long until the time when the birds shall fly forth...in order that the corpse be attended to, the Dakhmas attended to, the impurities attended to, and the birds gorged.” Another text read the corpse is “exposed to dogs and vulture, so as to benefits in this way the animals of the good creation.”

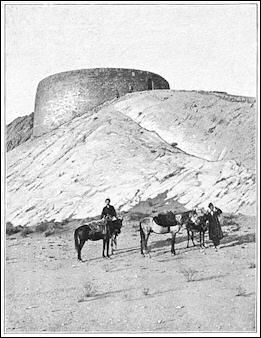

Towers of Silence

Bombay Temple Of Silence Engraving The Tower of Silence (“dokma” ) is usually built on a hilltop and made from stones or bricks. Typically they about five meters high and maybe 30 meters across., with an internal platform on which sit three ranks of stone slabs, on which the bodies of men , women and children are placed. They slope downwards towards a central dry well. The Tower of Silence is closed to everyone but special corpse handlers.

Describing a Tower of Silence in Bombay, one Professor Minier Williams wrote in the Times in 1876, “Towers of Silence are erected on a grade, on the highest point on Malabar Hill... five circular structures which appear at intervals rising above the foliage..They are simply masses of mason, massive enough to last for centuries, built of the hardest black granite, and covered with white chunam...Towers they scarcely deserve to be called: for the height of each is quite out of proportion with the diameter. A sixth tower stands quite apart from the others. It is square in shape, and used for person who have suffered death for heinous crimes.”

On one of the towers he wrote: “Imagine a round column or massive cylinder 12 to 14 feet high, and at least 40 feet in diameter, built thoroughly of solid stone, except in the center, where a well of 5 or 6 feet across leads down an excavation under the masonry, containing four drains at right angles to each other, terminated by holes filled with charcoal. Round the upper surface of this solid circular cylinder and completely hiding the interior from view is a stone parapet 10 or 12 feet in height.” With the parapets is a “circle of open stone coffins divided from the next by a pathway, so that there are three circular pathways...In the outermost circle of the stone coffins are placed the bodies of males, in the middle of this females, and in the inner and smallest circle, nearest the well, those of children.”

There is a Parsi "Tower of Silence" in Mumbai. In Iran Tower of Silences are no longer used. There the body is first placed on a metal stretcher with legs that keeps the body separated from the ground and then is placed in a cement grave.

India has lost more than 95 percent of its vultures. No one is sure why although pesticide-contaminated carrion is a prime suspect. Among those affected are the Parsis who have traditionally had vultures consume their dead in hilltop Towers of Silence. In response to the problem Parsis have enlisted the National Birds of Prey Center in England to help design a breeding program. In the meantime Parsis must rely on nature to dispose of bodies — about three a day — and are looking at other methods that fit their religion beliefs. In Mumbai there is discussion of building a huge aviary outside of the Towers of Silence to keep the vultures from flying away and eating carrion contaminated with pesticides.

Preparation of the Corpse in a Zoroastrian Funeral

Building used in the

Zoroastrian death ceremony As a person dies he is expected to utter a prayer praising the righteous and a prayer for penance. If he dies suddenly his close relatives are expected to say these prayers quietly in the ear of the deceased.

Ideally, the body is prepared on the same day that death occurs. Rich and poor are treated exactly the same. After death the corpse is shrouded in a white cotton cloth and bathed in cow’s urine and water. A sacred thread is wrapped around the body while a special prayer is said. After this the corpse is wrapped in old clothing (wasting new clothes on the dead is considered sinful) and relatives embrace the dead a final time. After this the body is regarded as in a state of decomposition and too polluted for ordinary people to come in contact with. All procedure from then on are taken care of by special corpse handlers.

The corpse handlers ritually wash themselves and put on clean but old clothes which are disposed of after the funeral is over. They then place the corpse in a special white robe, set up the body in a special way, and place it in a funerary room on a stone slab, so it doesn’t come in contact with the earth, with the head pointing north. Three concentric circle are drawn around the slab and a fire with sandalwood and incense and a lamp burning coconut oil are lit.

After that a special “four eyed” dog — with spots on its forehead — is brought in to make sure the person is truly dead (if the dog shows an interest in the body it means it is dead, if it looks away the body is checked to see if it is alive. The gaze of the four-eyed is thought to confuse evil spirits.

Towers of Silence at a Zoroastrian Funeral

Tower of Silence An hour before the corpse is carried to the Tower of Silence, priests enter the funerary room and perform a special ritual that involves saying blessings and chanting hymns. Then while people turn their backs to the corpse, which is believed to throw out polluting germs when it is moved, the corpse is lifted and placed on a bier and taken to the Tower of Silence in a precession attended only by male mourners and corpse handlers.

After the body is laid in the tower, according to Zoroastrian texts, the copse bearers “tear off the clothes from the body of the deceased and leave it [the body] on the floor of the Tower...The body must be exposed and left party uncovered, so as to draw towards the eye of the flesh-devouring birds and fall easy prey to them. The sooner it is is devoured, the lesser the chance of further decompositions and the greater sanitary good and safety.”

The corpse is placed in the Tower of Silence. The flesh is removed, mostly by vultures and birds of prey. It usually takes around an hour for the flesh to be picked clean from the bones. On the funeral of a child Williams wrote: “The two [corpse] bearers speedily unlocked the door, reverently conveyed the body of the child into the interior, and, unseen by any one, laid it uncovered in one of the open stone receptacles nearest the central well. In two minutes they re-appeared with the empty bier and white cloth; and scarcely had they closed the door when a dozen vultures swooped down upon the body, and were rapidly followed by others. In five minutes more we saw the satiated birds fly back and lazily settled down again upon the parapet. They had left nothing behind but skeleton.”

A few days later the corpse bearers return and throw the bones down the central well. The well has charcoal and sand in it. the purpose of the charcoal is to protect the earth from the polluting qualities of the dead. Williams wrote: “In a fortnight, or at most four weeks, the same bearers return, and with gloved hands and impalements resembling tongs place the dry skeleton in the central well. There the bones find their last resting place, and there the dust of whole generations of Parsees commingling is left undisturbed for centuries.”

If no Tower of Silence exists the dead are placed in a tree for vulture to devour or are buried or cremated. Cremation and burial is frowned upon because it pollute the earth. Parsis living in the United States, Britain and other countries where leaving bodies for vultures is not allowed practice cremation. According to an ancient text: “It is said the body of a male Persian is never buried, until it has been torn ether by a dog or a bird of prey.” Vulture never attack the living. There are a couple of cases of people who were not dead being taken to the Tower of Silence. The towers have chains so such person can pull themselves up and be rescued. In Bombay those that survived the towers were ostracized and not allowed to mingle with ordinary people.”

Zoroastrian Mourning

Tomb in Sulaymaniyah province Relatives often used to camp out by the remains for two or three days while and after the vultures did their work. Zoroastrians believe that the soul remains earthbound for three days so during that time they say prayers and make offerings to the dead.

Even after the dead have left the earth, Zoroastrians believe they have the power to affect the living and bring fertility, prosperity, luck, hardships and sickness to the land and people. For these reasons offerings are made every day for 30 days; monthly for a year; and yearly for 30 years — when it is believed that the dead is finally absorbed completely into its place in the afterlife. Offerings of wine, milk, pomegranates and quince are made. Sometimes special animal sacrifices are made.

During the last ten days of the year, a special festival is held that honors all the dead. During this time people carefully clean their houses, fill them with juniper incense and display the best possible behavior. A special prayer is said for the dead who are believed to visit their former homes on this day.

During Farvardegan, a holiday in which the dead are remembered, seven different kinds of greens are sewn to welcome the spirits with freshness. Many Zoroastrians believe that the world of the dead coexist with the world of the living and dreaming is a form of communication between the two worlds and the soul wanders from the body during dreams.

Zoroastrians in Iran

ruined fire temple Ani There are believed to be less than 30,000 Zoroastrians left in Iran. They are mostly in Tehran, Yazd and Kerman. Many of those that lived in Iran at the time of the Shah left after the Islamic revolution in 1979. Many emigrated to the West. Those that remained were discriminated against and practiced their religion quietly at home. Their festivals were strongly and anything to do with fire worship was discouraged.

In the 1950s about 40 percent of Zoroastrians lived in villages. By the 1980s only 15 percent did. Today, most live in Tehran to take advantage of the economic opportunities there. A number of former Zoroastrians villages are now abandoned. In the 1970s there were only 15 Zoroastrian priests in Iran.

Yazd and villages around it have traditionally been home to many Zoroastrians. Desert shrines here attract Zoroastrian pilgrims from all over the world. Many of the Zoroastrian villages are now derelict. Their residents have moved to Tehran, India or the West. The number of Zoroastrians living in Yazd has been declining steadily. Early in the 19th century there were around 8,000 living there. By the 1980s there were less than 5,000.

Zoroastrians endured a great deal of persecution and discrimination over the centuries. Until the 19th century, they were forbidden from engaging on any trade or craft that would bring them in close contact with Muslim. Until the 1890s they could not use umbrellas, wear glasses and were forced to twist turbans instead of folding them. Because they feared attacks from Muslim extremists they often hid the locations of their fire temples. Many were farmers. Other sought education and became teachers, doctors, engineers and businessmen. Some became quite wealthy. To maintain good relations they donated money to build schools. hospitals and cultural centers.

Zoroastrian Life in Iran

Zoroastrians in Iran speak their own special dialect in addition to of Farsi. Some scholars have classified it as a dialect of Dari. In many ways their lifestyle today is indistinguishable from other Iranians but that wasn’t always so. In the old days they lived in houses that conformed to restrictions imposed on them but also had features that were needed for their religion and protection from Muslim extremists. The houses in Yazd had a great hall and small hall, rooms used for religious practices, and an open hearth in the kitchen where a sacred fire was kept burning. They lacked wind towers and instead had a number of vents on holes in the roof to help circulate the air.

Mehregan Table for the

Persian Autumn Festival Kin relationships are strong. Relatives are expected to be financially supportive of one another. Marriages are viewed as unions of families rather than individuals and marriages between cousins and next of kin have traditionally been preferred to keep wealth within the family. These customs have led to a problem of inbreeding and resulting high rates of mental retardation, diabetes and heart diseases. Because many young Zoroastrians are moving to the United States and Europe and marrying non-Zoroastrians there is a worry that the group may become extinct. This has led to acceptance of conversion to Zoroastrianism, a sometimes complex process usually associated with marriage that demands the non-Zoroastrians to learn Zoroastrian rituals and prayers and requires the approval of seven Zoroastrians that the new convert is a worthy individual of good character.

There is no supreme Zoroastrian leader on Iran. In each major community there is an association with an affiliated youth group. These days few participate in temple centered activities.

Zoroastrian and Iranian Holidays

Zoroastrians and Iranians celebrate Iranian New Year (Nowruz, or Noroz), which is celebrated in March and has Zoroastrian influences. People light bonfires, set of firecrackers and dance in the streets to leave their failures behind them and start the new year with prosperity.

Zoroastrians hold major festivals in the spring and the fall; and honor the dead at the end of the year. These are often celebrated at temples.Ceremonies for marriage, initiation, death and the seasons are usually conducted at home. Full and new moons are marked with offerings of dried leaves of herbs and animal fat.

Many Iranians still celebrate Chahar Shanbeh Suri (The Feast of Wednesday), or Feast of Fire. Held around Iranian New Year in the spring. It is marked by public bonfires and leaping over fires of “boteh” , or desert thorn, and chanting in Farsi: “My troubles and my age I cast into your flames: give me your warmth and brightness in return.” The ritual is believed to be rooted in Zoroastrianism.

Yazd Zoroastrian temple On the Winter solstice, the longest night of the year, Iranians buy fruit, nuts and other goodies to mark the feast of Chellah, also known as Yalda, an ancient tradition when families get together and stay up late, swapping stories and munching snacks.

In February, 2010 for the first time in a long time thousands of Iranians gathered in a snowy mountain in Cham to light giant fires to celebrate Sadeh, the ancient Zoroastrian mid-winter festival with Iran’s dwindling community of Zoroastrians. There was even a police band on hand that played the Iranian national anthem and other patriotic songs.

The enthusiasm was seen as a sign that Iranians were tiring of life under the Islamic regime and were expressing more interest in Iran’s ancient cultures. One Iranian Muslim who took part, told AP: “I’m proud of Sadeh because it is part of Iran’s cultural heritage. Once it was a national celebration and for centuries it has been restricted to Zoroastrians but there is no reason why Iranian Muslim should not celebrate the event.”

In March 2001, 1,200 people were arrested a Feast of the Fire celebration in Tehran for “selling firecrackers” and “disrupting public calm”.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2019