ISLAMIC LEADERSHIP AFTER MUHAMMAD

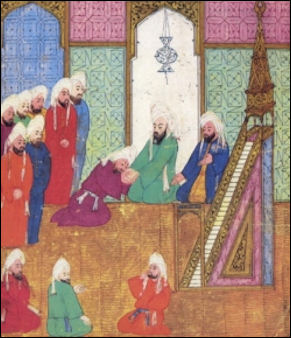

Muhammad in Paradise with Uthman, Umar and Abu Bakr

John L. Esposito wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”:After the death of Muhammad, his four immediate successors, remembered in Sunni Islam as the Rightly Guided Caliphs (reigned 632–61), oversaw the consolidation of Muslim rule in Arabia and the broader Middle East (Egypt, Palestine, Iraq, and Syria), overrunning the Byzantine and Sasanid empires. A period of great central empires was followed with the establishment of the Umayyad (661–750) and then the Abbasid (750–1258) empires. Within a hundred years of the death of Muhammad, Muslim rule extended from North Africa to South Asia, an empire greater than Rome at its zenith. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Each of these caliphs had been a close companion to Muhammad, and all belonged to the Quraysh tribe. The period of their rule is considered the golden age of Islam, when rulers were closely guided by Muhammad's practices. Even so, during the early period of the Arab conquests, many of the people who were close to Muhammad or his family were lost, with them was lost valuable information about the Qur’an and Muhammad. The early period was also characterized by the unification of Arab tribes that had traditionally been independent and were more used to living in a state of virtual anarchy than one of institutional order.

Islamic History: History of Islam: An encyclopedia of Islamic history historyofislam.com ; Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sacred Footsetps sacredfootsteps.com ; Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate” by Wilferd Madelung Amazon.com ;

“Caliphate: The History of an Idea” by Hugh Kennedy Amazon.com ;

“Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In”

by Hugh Kennedy Amazon.com ;

“In God's Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire” by Robert G. Hoyland, Peter Ganim, et al. Amazon.com ;

“In the Shadow of the Sword: The Birth of Islam and the Rise of the Global Arab Empire

by Tom Holland, Steven Crossley, et al. Amazon.com ;

“After the Prophet: The Epic Story of the Shia-Sunni Split in Islam” by Lesley Hazleton and Blackstone Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs: A History” by Eugene Rogan Amazon.com ;

“The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 1, Formation of the Islamic World, 6th to 11th Centuries Amazon.com ;

“Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes, and Empires” by Tim Mackintosh-Smith, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs in History” by Bernard Lewis Amazon.com ;

“History of Islam” (3 Volumes) by Akbar Shah Najeebabadi and Abdul Rahman Abdullah Amazon.com ;

“Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Muslim World: From Its Origins to the Dawn of Modernity”

by Michael A. Cook, Ric Jerrom, et al. Amazon.com ;

”History of the Arab People” by Albert Hourani (1991) Amazon.com ;

“Islam Explained: A Short Introduction to History, Teachings, and Culture” by Ahmad Rashid Salim Amazon.com ;

“No God but God” by Reza Aslan Amazon.com ;

“Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time” by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“The Messenger: The Meanings of the Life of Muhammad” by Tarqi Ramadan Amazon.com

Period After Muhammad's Death

By his death in 632, Muhammad enjoyed the loyalty of almost all of Arabia. The peninsula's tribes had tied themselves to the Prophet with various treaties but had not necessarily become Muslim. The Prophet expected others, particularly pagans, to submit but allowed Christians and Jews to keep their faith provided they paid a special tax as penalty for not submitting to Islam. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992 *]

For the first 30 years following the Prophet’s death, caliphs ruled the Islamic world from Yathrib, today known as Medina. Responding to threats from the Byzantine and Persian empires, the caliphs demanded allegiance from the Arab tribes. In a relatively short span of time, the Islamic empire expanded northward into present-day Spain, Pakistan, and the Middle East. However, maintaining unity proved to be a continual challenge. Following the death of the third caliph, Uthman, in 656, splits appeared in the burgeoning Islamic empire. The Umayyads (661–750) established a hereditary line of caliphs centered in Damascus. The Abbasids, claiming a different hereditary line, overthrew the Umayyads in 750 and moved the caliphate to Baghdad. Although the spiritual significance of Mecca and Medina remained constant, the political importance of Arabia in the Islamic world waned. [Source: Library of Congress, September 2006 **]

After Muhammad's death, his followers compiled those of his words regarded as coming directly from God into the Quran, the holy scriptures of Islam. Others of his sayings and teachings, recalled by those who had known him, became the hadith. The precedent of Muhammad's personal behavior is called the sunna. Together they form a comprehensive guide to the spiritual, ethical, and social life of the orthodox Sunni Muslim. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, Library of Congress, 1988 *]

Political Turmoil Over Muhammad's Successor

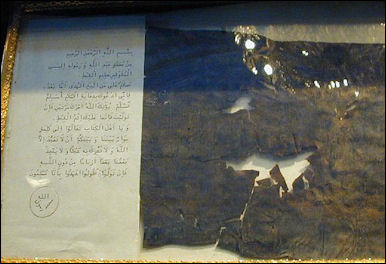

Muhammad's letter to Muqawqi When Muhammad died the Muslim world was thrown into turmoil because there were no obvious successor since his only surviving children were daughters. To help Muslim keep the focus on what really mattered, Abu Bakr proclaimed: “O men if you worship Muhammad, Muhammad is dead; if you worship God, God is alive.

The was a great debate about what form Islam should take and how it should be organized. Some believed that each tribal group and community should be lead by imam, and that is high as high as the hierarchy should go. Others felt that Muslims need to be united as they were under Muhammad.

From the very beginning Islam had a political side that was not well defined and this has generated problems every since. The selection of first Caliph was carried out by the Medina Muslim community and was done without defining authority or rules of selection. The only guidance left for future generations were the laws of Islam itself, with no distinction being made between the religious and political aspects of the community. There never really has been a Muslim equivalent of separation of church and state.

After Muhammad's death in A.D. 632 the leaders of the Muslim community chose Abu Bakr, the Prophet's father-in-law and one of his earliest followers, to succeed him as caliph (from khilafa; literally, successor of the Prophet). At that time, some persons favored Ali, the Prophet's cousin and husband of his daughter Fatima, but Ali and his supporters recognized the community's choice. The next two caliphs, Umar and Uthman, enjoyed the recognition of the entire community, although Uthman was murdered. When Ali finally succeeded to the caliphate in 656, Muawiyah, governor of Syria, rebelled in the name of his kinsman Uthman. After the ensuing civil war Ali moved his capital to Kufa (present-day Karbala in Iraq), where a short time later he too was assassinated. [Source: James Heitzman and Robert Worden, Library of Congress, 1989 *]

Ali's death ended the last of the so-called four orthodox caliphates and the period in which the entire Islamic community recognized a single caliph. Muawiyah then proclaimed himself caliph of Damascus. Ali's supporters, however, refused to recognize Muawiyah or his line, the Umayyad caliphs; they withdrew in the first great schism of Islam and established a dissident faction known as the Shias (or Shiites), from Shiat Ali (Party of Ali) in support of the claims of Ali's line to the caliphate based on descent from the Prophet. The larger faction of Islam, the Sunnis, claims to follow the orthodox teaching and example of Muhammad as embodied in the Sunna, the traditions of the Prophet. The Sunni majority was further developed into four schools of law: Maliki, Hanafi, Shafii, and Hanbali. All four are equally orthodox, but Sunnis in one country usually follow only one school. *

Originally political in nature, the difference between the Sunni and Shia interpretations took on theological and metaphysical overtones. Ali's two sons, killed in the wars following the schisms, became martyred heroes to Shia Islam and repositories of the claims of Ali's line to mystical preeminence among Muslims. The Sunnis retained the doctrine of leadership by consensus. Despite these differences, reputed descent from the Prophet still carries great social and religious prestige throughout the Muslim world. Meanwhile, the Shia doctrine of rule by divine right grew more firmly established, and disagreements over which of several pretenders had the truer claim to the mystical power of Ali precipitated further schisms. Some Shia groups developed doctrines of divine leadership, including a belief in hidden but divinely chosen leaders. The Shia creed, for example, proclaims: "There is no god but God: Muhammad is the Prophet of God, and Ali is the Saint of God." *

Mecca: the Heartland of Islam

Old Map of Mecca

Until about 900, the centers of Islamic power remained in the Fertile Crescent, a semicircle of fertile land stretching from the southeastern Mediterranean coast around the Syrian Desert north of the Arabian Peninsula to the Persian Gulf and linked with the Arabian heartland. After the ninth century, however, the most significant political centers moved farther and farther away — to Egypt and India, as well as to what is now Turkey and the Central Asian republics. Intellectual vitality eventually followed political power, and as a result, Islamic civilization was no longer centered in Mecca and Medina in the Hijaz. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992 *]

Mecca remained the spiritual focus of Islam because it was the destination for the pilgrimage that all Muslims were required, if feasible, to make once in their lives. The city, however, lacked political or administrative importance even in the early Islamic period. This devolved on Medina instead, which had been the main base for the Prophet's efforts to gain control of the shrines in Mecca and to bring together the tribes of the peninsula. After the Prophet's death, Medina continued to be an administrative center and developed into something of an intellectual and literary one as well. In the seventh and eighth centuries, for instance, Medina became an important center for the legal discussions that would lead to the codification of Islamic law. Orthodox (Sunni) Islam recognizes four systems--or schools--of law, and one of these, the school of Malik ibn Anas (died in 796), which is observed today in much of Africa and Indonesia, originated with the scholars of Medina. The three other Sunni law schools (Hanafi, Shafii, and Hanbali) developed at about the same time, but largely in Iraq.*

Under normal circumstances, Muslims visited Mecca every year to perform the pilgrimage, and they expected the caliph to keep the pilgrimage routes safe and to maintain control over Mecca and Medina as well as the Red Sea ports providing access to them. When the caliph was strong, he controlled the Hijaz, but after the ninth century the caliph's power weakened and the Hijaz became a target for any ruler who sought to establish his authority in the Islamic world. In 1000, for instance, an Ismaili dynasty controlled the Hijaz from Cairo.*

Caliphs

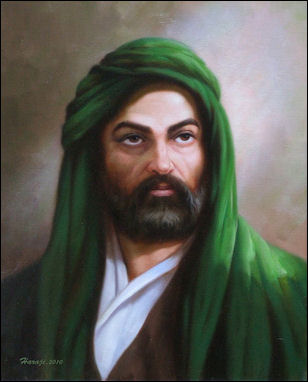

Abu Bakr The leaders that succeeded Muhammad were called Caliphs. Caliph is an Arabic that means "successor," "lieutenant" or "viceroy." It refers a supreme religious leader who is a descendent of Muhammad. They were powerful but they did not have the connection with divinity that Muhammad had. Additionally in the Muslim world, there were sultans, sovereigns of Muslim kingdoms.

Caliphs were not regarded as prophets or infallible interpreters of religious doctrines. They were religious and political leaders of the entire Muslim community and guardian of Muslim law and the Islamic holy sites. Their duty was to maintain peace and uphold the law in the Muslim community. Their qualifications included knowledge of religious laws and widely acknowledged virtuousness. It was also important for them to be linked by blood to Muhammad’s Quraysh tribe.

The first four Caliphs — Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali — were all from Mecca and all close friends or relatives of Muhammad. Later caliphs lived outside Arabia. They ruled over an empire that was considerably larger than the area that Muhammad presided over. Despite being greatly weakened after the 12th century caliphs endured for 1,300 years until the caliphate was abolished in 1924 by the leaders of modern secular Turkey.

See Separate Article: EARLY ARAB-MUSLIM RULE, CALIPHS AND SUNNI-SHIITE DIVISIONS africame.factsanddetails.com

Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr, the first caliph (reigned 632–34),was an old close, friend and advisor of Muhammad, his father-in-law and the father of his favorite wife, Aisha. He became caliph in a meeting of close friends of Muhammad and Muslim leaders even though many people thought Ali — Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law — was more deserving because he was a blood relative of Muhammad

Abu Bakr was an early convert to Islam. Respected for his piety and sagacity, Abu Bakr had been the one appointed to lead the Friday communal prayer in Muhammad's absence. After Muhammad's death the leaders of the Muslim community consensually chose Abu Bakr as Muhammad's successor. The community that selected him were called Sunnis, or followers of the sunnah (example) of the Prophet, based on their belief that leadership should pass to the most qualified person. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Abu Bakr maintained the loyalty of the Arab tribes by force, and in the battles that followed the Prophet's death — which came to be known as the apostasy wars — it became essentially impossible for an Arab tribesman to retain traditional religious practices. Arabs who had previously converted to Judaism or Christianity were allowed to keep their faith, but those who followed the old polytheistic practices were forced to become Muslims. In this way Islam became the religion of most Arabs. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992]

Abu Bakr’s rule was short (two years) but critical to shaping Islam. He led the wars of “ribbah” (apostasy) against tribes that had seceded from the Muhammad’s tribal confederation. He subdued the revolt with great political skill and was able to keep Arabs unified after Muhammad’s death, no easy task.

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di, the great 10th century Arab historian, wrote: “Abu 'Bakr surpassed all the Muhammadans in his austerity, his frugality, and the simplicity of his life and outward appearance. During his rule he wore but a single linen garment and a cloak. In this simple dress he gave audience to the chiefs of the noblest Arab tribes and to the kings of Yemen. The latter appeared before him dressed in richest robes, covered with gold embroideries and wearing splendid crowns. But at sight of the Caliph, shamed by his mingling of pious humility and earnest gravity, they followed his example and renounced their gorgeous attire.” [Source: The Book of Golden Meadows, c. 940 CE , Charles F. Horne, ed., “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East,” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 35-89, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

Abu Bakr stops Meccan Mob

Umar and Uthman — the Second and Third Caliphs

Umar (Omar ibn al-Khattab, Caliph from 634-44) was the second caliph. He was seen as the dominant personality among the four caliphs after Muhammad and was responsible for establishing many of the fundamental institutions of the classical Islamic state. Umar was a devoted pagan and lover of poetry, until he was converted to Islam by the beauty of the language in Qur’an and married one Muhammad’s daughters. Umar is remembered most as a military leader, who was able harness the Arab raiding urges, which bubbled under the surface among Muslims who were not allowed to fight each other, into a campaign against non-Muslims, in the process creating a Muslim empire that stretched across the Middle East. Umar was assassinated in a mosque in Medina 644 by a Persian prisoner of war.

Uthman (Othman ibn Affan, Caliph from 644-56) was the third caliph. He was a young merchant from the powerful Umayyad family and the first Muslim from an influential family. Uthman was a very pious man. During his reign he Qur’an was collected and put into its final form. Uthman's lack of strength in handling unscrupulous relatives, however, led to his demise, and the ushering of a period of disorder and civil war. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Uthman was weaker than his predecessors but the Muslim empire continued to prosper and expand. However he alienated many Muslims, especially those who were close to Muhammad in Medina, by picking members of his family for high positions. Malcontents began looking to Ali as the answer to their problems. In 656 Uthman was assassinated by malcontent soldiers who broke into the caliph’s simple home and killed him. The killers believed they were carrying out God’s will and declared Ali as Caliph.

Ali — the Controversial Fourth Caliph

After the Prophet's death, most Muslims acknowledged the authority of Abu Bakr but not all did. At that time some persons favored Ali, Muhammad's cousin and the husband of his daughter Fatima, but Ali and his supporters (the Shiat Ali, or Party of Ali) eventually recognized the community's choice. The next two caliphs (successors) — Umar, who succeeded in A.D.634, and Uthman, who took power in A.D.644 — enjoyed the recognition of the entire community. When Ali finally succeeded to the caliphate in A.D.656, Muawiyah, governor of Syria, rebelled in the name of his murdered kinsman Uthman. After the ensuing civil war, Ali moved his capital to Iraq, where he was murdered shortly there after.

Ali Ali ibn Abi Talib (Caliph from 656-61) was the foruth caliph. Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law, he was the husband of Muhammad's favorite daughter Fatima and grew up in Muhammad’s household. Ali seemed like the natural choice to be the first caliph. He was the closest male relative of Muhammad and the first male convert to Islam. He was regarded as a good soldier, charismatic, and pious, and was known for the wisdom of his judgements — a saying of the Prophet goes: “Ali is special to me and I am special to him; he is the supporting friend of every believer” — but because he was still young and inexperienced Abu Bakr was picked as the first caliph.

When Ali became caliph he established his capital in Kufa, Iraq. He was supported by the people of Medina, Muslims who resented the Umayyads, and traditionalist Muslims, but he was not universally accepted. The Umayyad elite opposed him and his rise to caliph. The assassination which brought him to power compromised his authority. A civil war broke out soon after Ali became caliph between his supporters and those of Muawiya, a relative of Uthman. Ali too was assassinated while praying in a mosque.

Ali's death ended the last of the so-called four orthodox caliphates and the period in which the entire community of Islam recognized a single caliph. Muawiyah proclaimed himself caliph from Damascus. The Shiat Ali refused to recognize him or his line, the Umayyad caliphs, and withdrew in the first great schism to establish the dissident sect, known as the Shias, supporting the claims of Ali's line to the caliphate based on descent from the Prophet. The larger faction, the Sunnis, adhered to the position that the caliph must be elected, and over the centuries they have represented themselves as the orthodox branch.

Ali and the Early History of Shiites and Sunnis

The group that supported Ali as caliph became Shias (Shiites, derived from “shi’at “Ali” , “the party of Ali,”). They believe that Ali was Muhammad’s true successor because he was a blood relative of the prophet and was thus the only one capable of explaining Islam’s doctrines. They believed the caliph should be selected among his family members because they were more intimately acquainted with Muhammad’s thinking and lifestyle. Those that opposed Ali became Sunnis. They believed that the caliph, or leader of the Islamic community should be selected among the most qualified of his followers. Sunnis believed the heirs of Abu Bakr, Umar and Uthman were best suited for the task even though they were not blood relatives like Ali.

Ali supporters believed that succession should be based on heredity and thus considered the first three caliphs to be usurpers. Ali's political discourse, sermons, letters, and sayings have served as the Shia framework for Islamic government. Shia Muslims recognize only Ali, as well as the brief reign of Ali's son Hussein (reigned 661).

The split between Sunni and Shiite sects was also politically motivated like Henry VIII's split from the Catholic Church, and was partly a disputes over the wealth of the early Caliphs. One reason the conflict between the sects has persisted to this day, some have suggested, is because the two groups were never allowed to fight it out until one group extinguished the other.

See Separate Article: HISTORY OF SUNNI-SHIA DIVISIONS africame.factsanddetails.com

Beginning of Umayyad Dynasty

Muawiyyah (Caliph from 661-80) became the recognized caliph after Hasan’s retirement. He ruled from Damascus, Syria and established the Umayyad dynasty. The name is derived from Bani Umayyah, My'awiyah's clan within Muhammad's Quraysh tribe. Muawiyyah was the son of Abu Sufyan, an old enemy of Muhammad, and was the Governor of Syria.

After Ali’s death, Muawiyyah managed to restore unity to the Muslim empire. He was a good Muslim and able leader and kept order with an effective administration system and a strong government.

Yazd I (Caliph from 680-683) succeeded his father Muawiyyah as caliph. They was great resistance to the establishment of a dynasty. A civil war broke out that lasted from 680 to 692.

See Separate Articles Under UMAYYADS: africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024