LITERATURE IN THE EARLY ISLAMIC PERIOD

Antar, a popular hero that dates back to pre-Islamic times

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. Wrote in “A Concise History of the Middle East”: Almost every subject "is part of the literature of il the Muslim peoples. Poetry was also an important means of artistic expression, instruction, and popular entertainment. There were poems that praised a tribe, a religion, or a potential patron; some that poked fun at the poet's rivals; others that evoked the power of God and the exaltation of a mystical experience; and still others that extolled love, wine, or sometimes both (you cannot always be sure which). [Source: Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., “A Concise History of the Middle East,” Chapter. 8: Islamic Civilization, 1979, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu /~]

“Prose works were written to guide Muslims in the performance of worship, instruct princes in the art of governing, refute the claims of rival political and theological movements, or teach any of the 1001 aspects of living from cooking to lovemaking. Animal fables scored points against despotic rulers, ambitious courtiers, naive ulama, and greedy merchants. You probably know the popular stories that we call he Arabian Nights, set in Harun al-Rashid's Baghdad, but actually composed by many ancient peoples, passed down by word of mouth to the Arabs, and probably set to paper only in the fourteenth century. You may not have heard of a literary figure equally beloved of the peoples of the Middle East. The Egyptians call him Goha, the Persians say he is named Mollah, and the Turks refer to him as Nasruddin Hoja. One brief story will have to suffice. A man once complained to Goha that there was no sunlight in his house. "Is there sunlight in your garden?" asked Goha. "Yes," the other replied. "Well," said Goha, "then put your house in your garden."

Websites and Resources: Islam Islam.com islam.com ; Islamic City islamicity.com ; Islam 101 islam101.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org/islam ; BBC article bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam ; Patheos Library – Islam patheos.com/Library/Islam ; University of Southern California Compendium of Muslim Texts web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on Islam britannica.com ; Islam at Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Islam from UCB Libraries GovPubs web.archive.org ; Muslims: PBS Frontline documentary pbs.org frontline ; Discover Islam dislam.org ;

Islamic, Arabic and Persian Literature

Islamic and Arabic Literature at Cornell University guides.library.cornell.edu/ArabicLiterature ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ;

Wikipedia article on Islamic Literature Wikipedia ;

Wikipedia article on Arabic Literature Wikipedia ;

Wikipedia article on Persian Literature Wikipedia ;

Persian literature at Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ;

Persian Literature & Poetry at parstimes.com /www.parstimes.com ;

Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

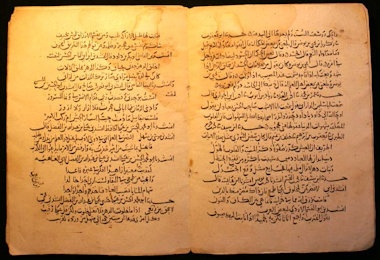

Writing and Manuscripts and under the Abassids

Abbasid manuscript

Paper was introduced to the Middle East from China in the 8th century. Gaston Wiet wrote in “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate": “In the meantime, the paper industry was born. After the battle of Talas [A.D. 751] in the Ili Valley at the end of the Umayyad period, a Chinese prisoner of war had been brought to Samarkand. There he began a paper industry using linen and hemp, imitating what he had seen in his own country. In 795, mention is made of the creation of the first paper factory in Baghdad. For a long time Samarkand remained the center of the industry, but, in addition to Baghdad, paper was manufactured in Damascus, Tiberias, Tripoli in Syria, Yemen, the Maghreb, and Egypt. The city of Jativa in Spain was famous for its thick, glazed paper. [Source: Gaston Wiet, “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate,” Chapter 5: the Golden Age the Golden Age of Arab and Islamic Culture translated by Feiler Seymour University of Oklahoma Press, 1971 ]

“After the appearance of paper, the number of manuscripts multiplied from one end of the Moslem empire to the other. This prosperous period for the publishing and selling of books was essential for cultural development. Paper was, therefore, of prime importance in the ninth century. From then on the book business was established in the Orient. However, we do not know whether the publishing was done by the author, a specialized merchant, or both at the same time. Well-stocked bookshops were often set up around the main mosque. Scholars and writers met in them, and copyists were hired there. In addition to the public libraries open to everyone, Jean Sauvaget, quoting an Arab source, spoke of "reading rooms where anyone, after paying a fee, could consult the work of his choice."

“Readers squabbled over works copied by well-known calligraphers, whose names were scrupulously recorded in the chronicles. The main libraries had their official copyists and their appointed binders. Wealthy writers had teams of such people. As is well known from monuments and manuscripts, calligraphy was an important art in Moslem countries. The most famous of the calligraphers of the time was Ibn Muqla, who was unfortunate enough to have been the vizier of three caliphs, an honor that earned him the cruel punishment of having his right hand amputated. It is said that he attached a reed pen to his arm and wrote so well that there was no difference between the way he wrote before and after he lost his hand.

“Baghdad had become an intellectual metropolis, an achievement which was to overshadow the elorts made by its two rival cities, Kufa and Basra. The work of the en- thusiastic translators was only the beginning; there was a very intimate rapport between the Arab writers and Greek thought, and the attempted assimilation was often quite successful.

Literature Under the Abbasids

Gaston Wiet wrote in “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate": “The Abbasid golden age gave rise to a capable and imposing group of translators, who tried successfully to regain the heritage of antiquity. Men of letters took advantage of this substantial contribution. They entered into passionate and fruitful discussions, which were dominated by the astonishing personality of Jahiz (d.868). He is probably the greatest master of prose in all Arab literature. He was a prolific writer with a vast field of interest. In addition, his Mutazilite convictions made him a literary leader. In order to describe reality, he broke with a tradition which was bound to the past. He laid the foundations of a humanism which was almost exclusively Arab and hostile to Persian interference at the beginning, and which took on more and more Greek coloration later on. His love of knowledge and his great intellectual honesty are evident on every page of his works. Jahiz is outstanding because of his exceptional genius, his qualities of originality, and his art in handling an often cruel and sometimes disillusioned irony, in which he was more successful than any writer before him. Jahiz pushed sarcasm to the point of mocking irreverence toward Divinity, more in the style of Lucian than of Voltaire. It is due to the tremendous talent of this prodigious artist that Arabic prose became more important than poetry. [Source: Gaston Wiet, “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate,” Chapter 5: the Golden Age the Golden Age of Arab and Islamic Culture translated by Feiler Seymour University of Oklahoma Press, 1971 ]

House of Wisdom

“Another great writer, Ibn Qutaiba, ranks high, immediately after Jahiz, whom he survived by about twenty years (d.88g). He too had an intellectually curious mind which made him a grammarian, a philologist, a lexicographer, a literary critic, a historian, and an essayist. In literature, he is an advocate of conciliation, through conviction and not lassitude, and a partisan of the golden mean. His Book Of Poetry, which shows him to be a creator of the art of poetry, contains judgments of great value.

“Ibn Duraid is worthy of mention because of the role re- cently attributed to him by an Arab critic as creator of the Maqama, of the Seance, which will be discussed later. This philologist is one of the last contestants in a battle which, during his lifetime, interested very few men of letters, the battle against Iranophilia.

“Mas'udi must certainly not be neglected, not only because he was born in Baghdad but because this tireless traveler has left us a most interesting account of the history of the Abbasid caliphate. The writer of memoirs, Suli, is of interest because he speaks of events of which he was a sad and, at times, indignant witness. His contemporary, Mas'udi, says, "He reports details which have escaped others and things which he alone could have known."

“The date of Tanukhi's death (994) places him in the Buyid period, as does his style, but in one of his works he speaks especially of the upheaval during Muqtadir's reign. Although it was meant to entertain, this book, written in a lively style, contains a good deal of solid judgment. Another short work consists of a series of amusing, merry stories which, if taken too seriously, might give a disturbing picture of the Baghdad bourgeoisie. It is dangerous to generalize, since the book is probably about a circle of party-goers and unscrupulous revelers. In short, reading Tanukhi is quite arnusing.

“It is impossible to mention all the prose writers who added to the glory of the ninth century in the Arabic language. Those who spent several years in Baghdad profited from the extraordinarily feverish atmosphere of the place. We must not omit Ya'qubi, the geographer, who left us exciting pages on the founding of Baghdad, and Ibn Hauqal who used Baghdad as the point of departure for his voyages.”

Arab Poetry

Diʻbil al-Khuzāʻī Arabic Praise poetry on Ali al-Ridha-Tiling-Balasar Mosque

Partly because of its association with the Qur’an and god, poetry has traditionally been considered the highest Arab-Muslim cultural form. Most of the Arab world's most famous literary figures have been poets. They have often been regarded as men blessed or cursed with special talent denied ordinary men, in some cased from demons.

Muslim poets wrote love songs rich in betrayal and sensual imagery, usually accompanied by musical instruments. Even Muslims who are illiterate can appreciate poetry because they recite and hear the poetic verses of the Qur’an every day.

In the pre-Islamic era poets acted as storytellers, historians, judges, philosophers and counselors. With the arrival of Islam, the rich language of the Qur’an because an expression of poetry in itself. In the courts of Baghdad and Damascus, poets were held in the highest of regard. Many famous poets seemed to have had drinking and women problems.

Popular styles of poetry included: 1) the “qasida”, an ode that originated in pre-Islamic times with accented meters and with a single rhyme running throughout it; 2) the “muwashshah”, a style that emerged in the 10th century and had a pattern of rhymes that appeared in a series of lines repeated throughout the poem. Among the most popular subjects were the exaltation of God, praise or rulers, odes to nature and romantic love and mysticism.

Poetry Under the Abbasids

Gaston Wiet wrote in “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate": “Under the Abbasids, there was also the social advancement of administrative secretaries, which enabled them to succeed the poets of an earlier period, who had been the only ones to earn their living in the field of letters. Thereafter the scholars, mathematicians, astronomers, astrologers, and translators of the works of Greek antiquity were supported by the first caliphs of Baghdad. [Source: Gaston Wiet, “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate,” Chapter 5: the Golden Age the Golden Age of Arab and Islamic Culture translated by Feiler Seymour University of Oklahoma Press, 1971 ]

“Songs and music are perhaps more important in Baghdad than in other regions of the Moslem world. There are great names in the field of theory, Farabi for example, and in composition, the Mausilis, father and son, and Ibrahim ibn Mahdi, the ephemeral caliph. During the reigns of several Abbasid caliphs, the Mausilis delighted the court of Baghdad. Ibrahim (804) had been the favorite of the caliphs Mahdi, Hadi, and Harun al-Rashid; he was the hero of some rather racy adventures. He led his musicians with a baton and was perhaps the first orchestra conductor. The great historian Ibn Khaldun wrote, "The beautiful concerts given at Baghdad have left memories that still last."

Poet Council of Al-Hakim II, Caliph of Cordoba

“Several poets gave accounts of the lives of the gay blades and the tough characters who frequented the cabarets of the capital. One small work, by Washsha, contains a sketch of the worldly manners and customs of the refined class of Baghdad and is a veritable manual of the life of the dandies of the period. It also gives minute details on dress, furniture, gold and silver utensils, cushions, and curtains, with their appropriate inscnptions.

“Another writer, Azdi, who is reminiscent of Villon, describes the society of debauched party-goers. His poems are difficult to translate because of their truculence, their strong language, and their defiance of decent morals. We should not be too surprised at the contrast between the studious world of the translator and the medical specialists and that of the writers of licentious poetry who sang, with some talent, of pleasure and debauchery and bragged of overtly displayed corruption.

Persian Influence on the Abbasids

Gaston Wiet wrote in “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate": “Moreover, the Iranization of the empire had an influence on the way of thinking, feeling, and writing. The discovery of Sassanian antiquity and Hellenic thought at the same time added fresh impetus. In the field of literature, there was a somewhat coordinated Iranophile movement called shu'ubiya. It consisted of a reaction, not always calm or tender, against Arab domination, both political and cultural. The promoter of this anti-Arab opposition was Sahl ibn Harun, director of the Academy of Wisdom, but in all fairness it should be said that even before him there were members of the fabulous Barmekid family who were prominent during Harun al-Rashid's reign because of their omnipotence and their tragic fate. They realized that poets played the same role as modern journalists. Poets should not, therefore, be led to oppose the regime. These great ministers were also famous for their broad tolerance; that the underlying motive was either coolness toward Islam or faithfulness to Iranian beliefs does not alter the facts. We know, for example, that a number of famous disputants among Islamic theologians, free-thinkers, and doctors of different sects met at the home of the educated and enlightened Yahya, the grandson of Barmek. [Source: Gaston Wiet, “Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate,” Chapter 5: the Golden Age the Golden Age of Arab and Islamic Culture translated by Feiler Seymour University of Oklahoma Press, 1971]

Arabic and Persian poetic verses

“Thus, in ninth-century Baghdad a fertile literary center was formed which lighted the way for Arab letters. Poetry continued to be cultivated with the same care. The poets of the Abbasid period were worthy of their great ancestors of pre-Islamic times and of the Umayyad court. A list of the poets of genius would include: Bashshar ibn Burd, who died in 783, the standard-bearer of the shu' ubiya and an erotic poet of great talent and robustness whose capabilities were rather disturbing from a religious point of view; Muti' ibn Iyas, who died in 787 as famous for his debauchery as for his blasphemy, as skillful in praising as in attacking; Saiyid Himyari, who died in 789 a more or less sincere panegyrist, who sought protection in the traditional way, who is particularly praised by the critics for his simplicity of style, and, as far as we are concerned, who escaped banality by his Shi'ite convictions, by the variety of his poetic themes, and by his artistic qualities; Abbas ibn Ahnaf, who died in 808 who speaks of the "power of love," always expressed his thoughts delicately and thus stands in opposition to the licentious poets who surrounded him, which explains his success in Spain; Abu Nuwas, who died in 8I3, the singer of the joy of living, the greatest Bacchic poet in the Arabic language, a sensual, debauched devil who became a hermit toward the end of his life and left a number of religious poems.

“Muti' ibn Iyas and Abu Nuwas, two great Iyric poets, had a pronounced taste for scandal and blasphemy. It would be an exaggeration to claim that they represented fairly accurately a certain aspect of Baghdad society. Yet, the smutty tales of the Book of Songs prove that the upper bourgeoisie was hardly overcome with moral scruples. Drunkenness was common, it seems, and perhaps even more violent thrills were sought. These poems, however, should be taken into account as a reflection of a part of society which was hungry for pleasure.

“Our honors list also includes Muslim ibn Walid, who died in 823 author of love poems and drinking songs; Abu Tammam (843) and Buhturi (897), famous for their original odes and their anthologies of poetry; Di'bil (960), who lived in peril because he associated with robbers and wrote satires in truculent and unpolished language; Ibn Rumi (896), whose verses include philosophical ideas and a close look at reality and whose satires are fine and cruel without being vulgar; Ibn Mu'tazz (908), who was caliph for one day and paid for it with his life, who, as a poet of transition, painted the society around him, describing the caliph's palaces in a rather delicate style, and who, in a moving poem, gave a glimpse of the future decadence of the caliphate; Ibn Dawud (9I0), leader of the school of courtly love and early ancestor of our troubadours; and, above all, the peerless Abul-Atahiya (825), the earliest Arab philosopher-poet, who wrote of suffering in verses that proclaim the vanity of the joys of this world. The anthologies of these poets were compiled perhaps to combat the Iranian spirit of the shu'ubiya in an attempt to conserve the masterpieces of the pre-Islamic period.”

Famous Poets from the Abbasid Period

from Confessions of Abu Nuwas

Abu Nuwas was a companion of the Baghdad Caliph Harun al-Rashid. He wrote many tributes to wine and appears to have been quite a rouge. One of his most famous lines goes: "”How can you but enjoy yourself/ When the world is in blossom,/ And wine is at hand?”" Al-Mutanabbi (915-68) is a legendary Arab poet born in Kufa whose names means “oracle.” When he was young he served as a court poet in Aleppo, Cairo, Baghdad and Shiraz. He was involved in politics and was murdered in a tribal feud by assassin who picked him out at random, not realizing he was a respected poet and sage. One of his most famous lines goes: “Not everything a man longs for is within his reach, for gust of winds can blow against a ship’s desires.”

In a tribute to his patron in Aleppo, who had just recovered from an illness, Al-Mutanabbi wrote: “Glory and honor were healed when you were healed, and pain passed from you to your enemies...Light, which had left the sun, as if its loss were a sickness in the body, returned to it...The Arabs are unique in the world in being of his race, but foreigners share with Arabs in his beneficence...It is not you alone I congragualte on your recovery; when you are well all men are well.”

Yunus Emre was a 13th century poet who wrote about universal love, friendship and divine justice. He lived in Anatolia from about 1228 to about 1320 and was a member of a Sufi sect of Muslims. His poems were about the search of spirituality, emphasizing the soul of the individual rather than formal religion. Emre once wrote, “ We see all of mankind as one...Whoever does not look with the same eye upon all nations is a rebel against truth...God’s truth is lost on men of orthodoxy. One of his most famous couplets goes: “”God’s truth is an ocean, and dogma is a ship./ Most people don’t leave the ship to plunge into that sea”.”

Persian Poets

The Persian provinces produced some of Islam's greatest scholars and poets: Izami (died 1209), Hafez (died 1390), Saadi (died 1292) and the 10th century Samanid figures Avicenna and Omar Khayyan. Many of great "Persian" poets and literary figures were in fact Tajiks from Central Asia. Iranians love Sufi poets.

Omar-Khayyám (1048-1123) was a Persian mathematician who enjoyed drinking and writing fatalistic poetry. He is famous in the West for his Rubiayat, or quatrains, but he was best known in his time as a mathemitican and astronomer.

Alchemy of Happiness by al-Ghazali

Omar-Khayyám wrote: “I sometimes think that never blows so red/ The Rosse as where some buried Caesar bled.” “Rubaiyat of Mar Khayyam” was a popular book in the Victorian era. Produced by an American expatriate Elihu Vedder, it was filled with images of skulls, owls and lizards set to Omar verse.

Al-Ghazali

Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali (d. 1111) is one of the great poets and thinkers in Muslim history. He made great contributions to Islamic theology, philosophy, literature, science and legal scholarship. In Baghdad in 1095 he suffered a nervous breakdown due to questions about his faith that left him paralyzed and unable to speak. He went to Jerusalem and recovered by doing Sufi excercises and concluded that God could not be found in reason and rationality but was more likely to be discovered using the rituals of Sufi mystics who aimed to have a direct relationship with God. He returned to Iraq 10 years after his breakdown and wrote his masterpiece “The Revival of Religious Sciences”, which became the most quoted text after the Qur’an and the hadiths.

Al-Ghazali was sort of like of a Muslim equivalent of St. Augustine or Thomas Aquinas: someone who wrote beautifully and was able to bring religion down to earth so that it could be understood by ordianry people. In addition to writing about deep philosophical issues he also wrote about music and what heaven is like.

In “The Revival of Religious Sciences”, al-Ghazali offered inights into prayer and knowledge of God and provided spiritual justification for Muslim rules on ordinary activities such as washing, eating and sleeping so that Muslims could feel they were doing something more than just following rules and that the only infallible teacher was Muhammad. Other Al-Ghazali works included “The Deliverer of Error” and “The Incoherence of Incoherence”.

On Disciplining The Soul Al-Ghazali wrote: “"If his aspiration is true, his ambition pure and his concentration good, so that his appetites do not pull at him, and he is not distracted by the hadith an-nafs (discourse of the soul meaning egotism of the soul) towards the attachments of the world, the gleams of the Truth will shine in his heart. At the outset, this will resemble a brief, inconstant shaft of lightening, which then returns, perhaps after a delay. If it returns, it may be fleeting or firm; and if it is firm (thabit), it may or may not endure for some time. States such as these may come upon each other in succession, or only one type may be present. In this regard, the stages of God's saints (awliya) are as innumerable as their outer attributes and qualities". (Translation by Shaykh Abdal-Hakim Murad).

See Separate Article AL-GHAZALI (1058-1111), SUFISM AND SUNNI ISLAM factsanddetails.com

Arabian Nights

From Arabian Nights: "He had the gift of understanding the language of beasts"

The most famous book in Arabic literature is “Arabian Nights”, a collection of stories that may have descended from an old Persian book called “Thousand and One Nights”. No one knows where the stories originally came or when they were first told.

The stories from “Arabian Nights” remain popular today. The include classical tales of adventure, magic and wealth set among exotic Eastern settings with harems, bazaars and luxurious palaces. Many people are familiar with the famous stories of Sinbad, Aladdin and Ali Babi through films and children stories without knowing anything about the originals.

The fairy tales of “Arabian Nights” are believed to be mostly of Persian origin. The moral fables are distinctly Arabian. The tales of animals and beasts are thought to have come from India. Others are probably of Chinese, Japanese and Egyptian origin.

In the A.D. 8th century, the stories of “Arabian Nights fame” were introduced to the court of Harun al-Rashid, the Caliph of Baghdad and one the greatest rulers during the Arab Golden Age. A great patron of the arts, Harun loved the stories and storytellers flattered him by making him a central character of many of the stories, often as a ruler traveling in disguises among his subjects.

No original or authoritative copy of “Arabian Nights” exists. Up until the Middle Ages the stories continued to be passed on orally, with different storytellers telling different stories, and did not take their present form until around 1400 when Egyptian scholars began writing the stories down. Arabic manuscripts that have survived from this period contain about 200 stories. The Middle Easter scholar Edward Said has accused European translations of the stories as being the source of many of the stereotypes and misconceptions about Arabs and Muslims.

Famous stories in the West from “Arabian Nights” include “Sinbad the Sailor”, “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves”, and “Aladdin”. The famous tale of a flying carpet began when three brothers—Prince Ali, Houssain and Ahmed—peered through an ivory tube and saw that the princess they loved was dying. To get to her as quickly possible they flew on a magic carpet Lesser known stories include “The Young King of the Black Isles”, “The Three Sisters”, “The Enchanted Horse” and Prince Ahmen and Periebanou”.

See Separate Article ARABIAN NIGHTS: ALADDIN, ALI BABA, FARTS AND SEXY, CLEVER WOMEN factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018