ABBASID DYNASTY RULERS

Abbasid family tree

Abbasid Dynasty—Iraq (Muslim dates, Western dates): 132–656: 750–1258

Ruler, Muslim dates A.H., Christian dates A.D.

al-Saffah: 132–36: 749–54

al-Mansur: 136–58: 754–75

al-Mahdi: 158–69: 775–85

al-Hadi: 169–70: 785–86

Harun al-Rashid: 170–93: 786–809

al-Amin: 193–98: 809–13

al-Ma'mun: 198–218: 813–33

al-Muctasim: 218–27: 833–42

al-Wathiq: 227–32: 842–47

al-Mutawakkil: 232–47: 847–61

al-Muntasir: 247–48: 861–62

al-Mustacin: 248–52: 862–66

al-Muctazz: 252–55: 866–69

al-Muhtadi: 255–56: 869–70

al-Muctamid: 256–79: 870–92

al-Muctadid: 279–89: 892–902

al-Muktafi: 289–95: 902–8

al-Muqtadir: 295–320: 908–32

al-Qahir: 320–22: 932–34

al-Radi: 322–29: 934–40

al-Muttaqi: 329–333: 940–44

al-Mustakfi: 333–34: 944–46

al-Mutic: 334–63: 946–74

al-Ta'ic: 363–81: 974–91

al-Qadir: 381–422: 991–1031

al-Qa'im: 422–67: 1031–75

al-Muqtadi: 467–87: 1075–94

al-Mustazhir: 487–512: 1094–1118

al-Mustarshid: 512–29: 1118–35

al-Rashid: 529–30: 1135–36

al-Muqtafi: 530–55: 1136–60

al-Mustanjid: 555–66: 1160–70

al-Mustadi': 566–75: 1170–80

al-Nasir: 575–622: 1180–1225

al-Zahir: 622–23: 1225–26

al-Mustansir: 623–40: 1226–42

al-Mustacsim: 640–56: 1242–58

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di

“Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di (Masudi, Masoudi) (ca. 895?-957 CE) — "the Arab Suetonius" or "the Arab Herodotus" — specialized in a history which went beyond chronology to look at themes and individual anecdotes. His “Book of Golden Meadows” (c. 940 CE) includes detailed descriptions of the early Abbasid caliphs.

Charles F. Horne wrote: “Among the early chronicles of the Arabs, by far the most celebrated is the many-volumed work of Masoudi, called the "Book of Golden Meadows." It is a collection of interesting and sometimes scandalous anecdotes about anything and everything in the past, but chiefly about the earlier caliphs. Masoudi himself was born at Baghdad, but was, like many of his countrymen, a wanderer. After visiting all lands, he finally selected Egypt as his dwelling-place, and there died, probably in 957.”

Other versions of Al-Masudi’s works: 1) “Mas'udi, The Meadows of Gold The Abbasids, translated by Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone, (Kegan Paul, April 1989); “Islamic Historiography: The Histories of Masudi,” trans. Khalidi Tarif, (SUNY Press, 1975).

See Separate Articles HARUN AL-RASHID (786-809) AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF ISLAMIC CULTURE factsanddetails.com and AL-MANSUR (A.D. 754-775), THE BUILDER OF BAGHDAD factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Great Caliphs: The Golden Age of the 'Abbasid Empire” by Amira K. Bennison Amazon.com ;

“The Abbasid Caliphate” by Tayeb El-Hibri Amazon.com ;

“Caliphate: The History of an Idea” by Hugh Kennedy Amazon.com ;

“Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate” by G Le Strange Amazon.com ;

“The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance” by Jim Al-Khalili, Simon Vance, et al. Amazon.com ;

“1001 Inventions: The Enduring Legacy of Muslim Civilization: Official Companion to the 1001 Inventions Exhibition” by Salim T.S. Al-Hassani Amazon.com ;

“Pathfinders: The Golden Age Of Arabic Science” by Jim Al-Khalili Amazon.com ;

“The Umayyad Empire” by Andrew Marsham Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs: A History” by Eugene Rogan Amazon.com ;

“The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 1, Formation of the Islamic World, 6th to 11th Centuries Amazon.com ;

“Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes, and Empires” by Tim Mackintosh-Smith, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs in History” by Bernard Lewis Amazon.com ;

“History of Islam” (3 Volumes) by Akbar Shah Najeebabadi and Abdul Rahman Abdullah Amazon.com

Caliph Al-Mansur

Caliph Al-Mansur (ruled 754-75) was the second caliph of the Abbasid dynasty. Under the authorization of “special help” from God he murdered all the Shiite leaders he considered a threat. He decided to build a new capital, surrounded by round walls, near the site of the Sassanid village of Baghdad. His son called himself the “Guided One,” the Shiite equivalent of the Messiah.

Caliph Al-Mansur ended the practice of giving Arabs special privileges. Regional leaders were selected from among local ethnic groups. This was done not so much to create a more equal society but to win the support of landowners so as to establish a feudal style monarchy.

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di, the great 10th century Arab historian, wrote: “Al Mansur, the third Caliph of the house of Abbas, succeeded his brother Es-Saffah ("the blood-shedder"). He was a prince of great prudence, integrity, and discretion; but these good qualities were sullied by his extraordinary covetousness and occasional cruelty.”

See Separate Article: AL-MANSUR (A.D. 754-775), THE BUILDER OF BAGHDAD africame.factsanddetails.com

Caliphate of Al Mahdi

al-Mahdi dirham

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Mu ammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Man ūr, better known by his regnal name al-Mahdī "He who is guided by God"), was the third Abbasid Caliph, reigning from 775 to his death in 785. He succeeded his father, al-Mansur. During his rule the Abbasids engaged in several major battles with the Byzantines and the cosmopolitan city of Baghdad, attracting immigrants from Arabia, Iraq, Syria, Persia, and lands as far away as Afghanistan and Spain. Baghdad was home to Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians, in addition to the growing Muslim population. It became the world's largest city. Al-Mahdi continued to expand the Abbasid administration, creating new diwans, or departments: for the army, the chancery, and taxation. Qadis or judges were appointed, and laws against non-Arabs were dropped. New York Times Wikipedia]

There is some dispute over how Al-Mahdi died. One account said he fell off his horse while hunting and died. Another said he was poisoned by one of his concubines in 785 AD. The concubine, Hasanah, she was jealous of another female slave to who Mahdi was drawing closer to and her aim was to poison the rival. Hasanah prepared a dish of sweets and placed a poisonous pear at the top of the plate. The pit of the pear was removed and replaced with a lethal paste. She sent the dish to her adversary via a servant, however, Mahdi intercepted the plate and ate the pear without hesitation. Shortly afterward, he complained of stomach pain and died that night at 43 years old.

See Separate Article: AL MAHDI africame.factsanddetails.com

Harun al-Rashid

Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786-809) is the most famous of the Abbasid Caliphs. A contemporary of Charlemagne and perhaps the greatest ruler of the Arab world, he oversaw the Golden Age of Islamic culture as the Muslims made progress militarily against the Byzantines and nearly captured Constantinople. Harun al-Rashid helped established a unified Muslim law for the entire Muslim world. He ruthlessly crushed any opposition groups and this helped usher in a period of peace.

Harun al-Rashid was a far cry from the first caliphs, who lived humbly in rather modest homes and required that Muslim only prostrate themselves before God. Harun al-Rashid ruled like a classic grand monarch. He made his home in huge palaces and required courtiers to kiss the ground when they were in his presence. He was called the “Shadow of God on Earth” and was often accompanied by an executioner to show that he had the power of life and death. Much of the day to day duties of running the empire was left to his vizier. The military was dominated by Persians.

Under Harun the arts and music flourished; the "Arabian Nights" stories were collected and written down; mathematics, sciences and medicine were pursued; and the elite at least enjoyed themselves and the arts. Abu Nuwas, a poet friend of Harun al-Rashid, wrote: "How can you but enjoy yourself/ When the world is in blossom,/ And wine is at hand?"

See Separate Article: HARUN AL-RASHID africame.factsanddetails.com

Caliph al-Ma'mun

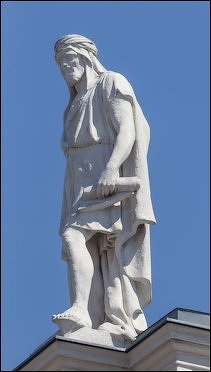

statue of Al Masudi in Austria

Abu al-Abbas Abd Allah ibn Harun al-Rashid 786/9– 833), better known by his regnal name al-Ma'mun, was the seventh Abbasid caliph, reigning from 813 until his death in 833. He succeeded his half-brother al-Amin after a civil war, during which the unity of the Abbasid Caliphate was weakened by rebellions and the rise of local warlords. Much of al-Ma'mun’s domestic rule was taken by pacification campaigns. Well educated and deeply interested in scholarship, al-Ma'mun promoted the Translation Movement, the flowering of learning and the sciences in Baghdad, and the publishing of al-Khwarizmi's book now known as "Algebra". He is also known for supporting the Islamic theological doctrine of Mu'tazilism and for imprisoning Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, the rise of religious persecution. Under his rule the Abbasids resumed large-scale warfare with the Byzantine Empire.. [Source: Wikipedia]

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu'di wrote: “When Harun Al Rashid died he left the empire to his sons Emin and Ma’mun, giving the former Iraq and Syria, and the latter Khorassan and Persia. Emin had the title of Caliph, to which Ma’mun was to succeed. War broke out between the brothers; Emin fled from Baghdad, but was captured and slain, and his head sent to Ma’mun in Khorassan, who wept at the sight of it. He had, however, previously, when his general Tahir sent to him requesting to know what to do with Emin in case he caught him, sent to the general a shirt with no opening in it for the head. By this Tahir knew that he wished Emin to be put to death, and acted accordingly. [Source: The Book of Golden Meadows, c. 940 CE , Charles F. Horne, ed., “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East,” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 35-89, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“The Caliph, however, bore a grudge against Tahir for the death of his brother, as was shown by the following circumstance: Tahir went one day to ask some favor from Al Ma’mun; the latter granted it, and then wept till his eyes were bathed in tears. "Commander of the Faithful," said Tahir, "why do you weep? May God never cause you to shed a tear! The universe obeys you, and you have obtained your utmost wishes." "I weep not," replied the Caliph, "from any humiliation which may have befallen me, neither do I weep from grief, but my mind is never free from cares."

See Separate Article: CALIPH AL MA’MUN africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024