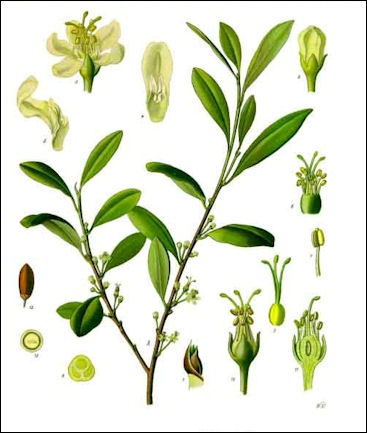

COCA PLANT

coca plant Coca is the source of cocaine. The coca plant is a shrub with two to seven centimeter (one to three inch) leaves, which contain an alkaloid that can be removed relatively easily and after a few more complicated steps made into the drug cocaine. There a 260 plants in the coca family that contain cocaine, but only four of them have usable amounts of the drug.

Coca plants resemble blackthorn bushes. They are usually about chest high although they grow to a height of three meters (10 feet). The leaves, the source of coca and cocaine, can be stripped off as many as eight times year. The plant produces flowers that are small and clustered on short stalks. The flowers mature into red berries. Neither the flowers or berries yield significant amounts of coca. The leaves are sometimes eaten by the larvae of the moth Eloria noyesi. [Source: Wikipedia]

Coca leaves contain one half of one percent of the active ingredient in cocaine. In valleys in Peru coca was grown legally in the 1980s and sold to ENACO, the Peruvian government coca monopoly. Small amounts of coca leaves are sold legally to drug manufacturers and Coca-Cola, who still uses a coca extract (with no cocaine in it) to flavor its cola. Many restaurants in Bolivia and Peru serve coca tea. It is recommended for tourist arriving by plane to the Andes highlands to help them adjust to the altitude. [Source: Peter White, National Geographic, January 1989]

Products made with powdered coca leaves include tea, flour, energy pills, energy bars, crackers, cookies, toothpaste, skin creams , toffee and soft drinks. A 1975 Harvard study cited the leaf’s protein, fiber and calcium content. Coca it turns out contains many nutrients: calcium, phosphorus, vitamins A and B2.

See Separate Articles:COCAINE: USE, EFFECTS, DANGERS AND HOW IT WORKS factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF COCA AND COCAINE factsanddetails.com ; COCAINE PRODUCTION: JUNGLE LABS, WORKERS AND COCA PASTE factsanddetails.com ; GLOBAL COCAINE TRADE factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) justice.gov/dea/concern ; Vaults of Erowid erowid.org ; United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) unodc.org ; Wikipedia article on illegal drug trade Wikipedia ; Illegal Drugs, country by country listing, CIA cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook ; Addiction Rehab Treatment is actively working to raise awareness on the health risks of cocaine addiction and the long-term effects. Addictionrehabtreatment.com offers addiction help and resources and helps people find a rehab facility if they are looking for it. addictionrehabtreatment.com

Books: “Illegal Drugs, Economy and Society in the Andes” by Francisco Thoumi (2003, Johns Hopkins University Press) is fascinating study of the Andean drug industry by an independent researcher with a Ph.D, in economics from the University of Minnesota. “Buzzed” by Cynthia Kuhn Ph.D. Scott Swartzwelder, Ph.D., Wilkie Wilson Ph.D. of the Duke University Medical Center (Norton, 2003); “Consuming Habits: Drugs in Anthropology and History” by Goodman, Sharratt and Lovejoy; “Drug War Heresies: Learning from Other Vices, Times and Places” by Robert MacCoun and Peter Reuter (Cambridge University Press).

Varieties of Coca Plant

There are two species of cultivated coca, each with two varieties: 1) Erythroxylum coca: A) Erythroxylum coca var. coca (Bolivian or Huánuco Coca) — adapted to the eastern Andes of Peru and Bolivia, an area of humid, tropical, montane forest; and B) Erythroxylum coca var. ipadu (Amazonian Coca) — cultivated in the lowland Amazon Basin in Peru and Colombia. Erythroxylum novogranatense; [Source: Wikipedia]

2) Erythroxylum novogranatense: A) ) Erythroxylum novogranatense: var. novogranatense (Colombian Coca) — a highland variety that is utilized in lowland areas cultivated in drier regions found in Colombia; and B) Erythroxylum novogranatense var. truxillense (Trujillo Coca) — grown primarily in Peru and Colombia.

All four of the cultivated cocas were domesticated in pre-Columbian times and are more closely related to each other than to any other species. E. novogranatense is very adaptable to varying ecological conditions. The leaves have parallel lines on either side of the central vein. Wild populations of Erythroxylum coca var. coca are found in the eastern Andes; the other three taxa are only known as cultivated plants.

The cocaine alkaloid content of dry Erythroxylum coca var. coca leaves range between 0.23 percent and 0.96 percent.

Coca Cultivation

coca bushes Coca is traditionally cultivated in the lower altitudes of the eastern slopes of the Andes (the Yungas), or the highlands depending on the species grown.

Coca grows best in a hot humid climate at an elevation of between 1,000 and 6,000 feet. It grows best on the temperate slopes on the east side of the Andes. Coca is grown primarily in the valleys and upper jungle regions of the Andean region, where Colombia, Peru and Bolivia are home to more than 98 per cent of the global land area planted with coca. In 2014, Coca plantations were discovered in Mexico, and in 2020 in Honduras. The quality of the leaves grown in Bolivia and Peru are regarded as higher quality than those grown in Colombia.

The seeds of the coca plant are generally sown from December to January in small plots sheltered from the sun. When the young plants reach about 40 to 60 centimeters (16 to 24 inches) in height they are placed in final planting holes, or if the ground is level, in furrows.The plants thrive best in clearings of forests but the most-desired leaves re obtained in drier areas, on the hillsides. [As coca plants mature they yield more of the leaves used to make cocaine. This means after coca plants are planted, there aren't many leaves the first year and it takes a few years before the bushes produce significant amounts of leaves. The leaves are gathered from plants varying in age from one and a half to upwards of forty years [Source: Wikipedia]

Only the new fresh leaves are harvested. They are considered ready for plucking when they break on being bent. The first and most abundant harvest is in March after the rainy season. There are other major harvests at the end of June and in October or November. The green leaves (matu) are spread in thin layers on coarse woollen cloths and dried in the sun; they are then packed in sacks, which must be kept dry in order to preserve the quality of the leaves.

Coca is an easy crop to grow, maintain, harvest and transport. It can be harvested multiple times a year. Most other crops in contrast can only be harvested once a year. Sometimes coca plants are grown on terraces that are somewhat reminiscent of those found on tea plantations. The leaves are often collected by peasant women who place the leaves in their aprons. Bags of coca are not heavy and be can easily be transported by plane or other means. Plane is preferable in case there are military roadblocks.

Coca Farmers

In Peru and Bolivia about 450,000 people make their living from coca. Many farmers who raised coffee, cacao and bananas during the 1970s switched to coca in the 1980's. Many leave the coca bushes virtually unattended and take a five day trek from their homes to the mountains, where the coca bush are, four times a year to harvest the leaves. Most people involved in cocaine look upon it strictly as a business or admit perhaps its wrong but then ask how else they are supposed to make a living. Those not in the cocaine business are often poor, living in houses without windows and descent lights, while those in the business have enough money to afford a nice house in Lima and send their kids to university. [Source: Peter White, National Geographic, January 1989]

A typical peasant farmer in the 1980s slashed and burned a six hectare (15 acre) plot out of the jungle: ten acres for coca and five acres for food such as maize or manioc. With proper weeding and fertilizing the leaves could be stripped every 35 days. An acre of coca trees produced about a ton of coca leaves, which yields about a half a kilogram (pound) of cocaine. Peasants growing coca earn about twice as much as they would growing coffee. About 200,000 to 400,000 hectares (a half million to a million acres) of land is believed to have been under cultivation for coca in the 1980s. [Ibid]

Coca prices go up and down. On average farmers are paid about $45 a load, which means a coca farmer growing four crops a year can earn about $700 an acre annually. (1992). In the mid-1980s, when times were good and prices were high, it was possible for a peasant farmer to make $7,000 a year growing about five acres of coca.

As many as 1 million of Colombia’s 50 million citizens are linked to the coca business directly or indirectly, according to Eduardo Diaz, a Colombian economist and former health minister. He told the Washington Post that coca is not lucrative for small farmers — even if it pays more than traditional crops. “And that’s the good news for us, because it makes it easier to succeed with alternatives.” As of 2015, two-thirds of Colombia’s 170,000 acres of coca fields were in national parks, indigenous reserves, border areas and other places off limits to spraying coca with herbicides according to the government,[Source: Nick Miroff, Washington Post, November 10, 2015]

In recent decades, especially after the break up of the Colombian drug cartels in the 1990, much of the territory on which coca was grown in Colombia was controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, a rebel group that fought the Colombian government for decades. FARC was a formidable guerrilla force. It initially “taxed” farmers’ coca production and went on to dominate trafficking in the areas under their control. Other armed groups — including ELN guerrillas, paramilitary gangs and the rural bands known as “bacrim” — in Colombia were also believed to have hands in the coca and cocaine trade.

Coca Producers

coca foliageThe world's largest producers of coca are Peru, Colombia and Bolivia. Which ones are dominant vary from time to time often based on the politics of cocaine at a given time. In the 1980s and early 1990s about 60 percent of the coca leaf produced was grown in Peru, with around 15 percent from Colombia and 22 percent from Bolivia. Most of the processing from cocaine base and paste to pure cocaine was done on Colombia.

In 1997, coca production dropped dramatically in Peru and dropped modestly in Bolivia but rose sharply in Colombia. By the early 2000s Colombia had become the leading coca grower. Coca leaf production in 2000 (in thousands of tons in 2000) was: 1) Colombia (266); 2) Peru (54); and 3) Bolivia (13). At the time much of the coca leaf production was in rebel-controlled territories in Colombia.

According to the UNODC: Following years of increase, coca bush cultivation decreased in 2019 Following a massive upward trend over the period 2013– 2017, during which the area under coca bush cultivation more than doubled, the size of the area under coca bush cultivation stabilized in 2018 and then decreased — for the first time in years — by 5 percent in 2019. This was mainly the result of a decrease reported by Colombia (9 percent); the area under coca bush cultivation remained stable in Peru and increased in the Bolivia (by 10 percent). In 2019, Colombia continued to account for the vast majority of the global area under coca bush cultivation (two thirds), Peru accounted for just under a quarter and the Bolivia accounted for 11 percent.2 In 2020, despite some disruptions in the cocaine manufacture supply chain at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, it did not seem that coca bush cultivation in any of the three countries was significantly affected by the restrictions implemented in response to the pandemic. [Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), World Drug Report 2021]

Coca Cultivation in Columbia

According to the UNODC: Coca bush cultivation has decreased in most parts of Colombia and is becoming increasingly concentrated The overall area under coca bush cultivation in Colombia decreased by 1 percent in 2018 and by 9 percent in 2019 compared with the previous year, with decreases observed in all the main coca bush-cultivating regions of the country other than Catatumbo (Departments of Norte de Santander and Cesar), which borders Venezuela. In 2019, coca bush cultivation was found in 22 of the 32 departments in Colombia; of those, 17 reported decreases in the area under cultivation compared with the previous year and reported increases. The increases were minimal in most cases, except for Norte de Santander, the department with the largest area under coca bush cultivation in 2019, where the increase was 24 percent. [Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), World Drug Report 2021]

Nonetheless, most of the coca bush cultivation in Colombia continues to take place in the south of the country, where the Departments of (in order of the size of the area under coca bush cultivation) Nariño, Putumayo, Cauca and Caquetá accounted for 54 percent of the total area under coca bush cultivation. The size of the area under coca bush cultivation decreased, however, in most of the country’s southern departments in 2019.

At the same time, coca bush cultivation is becoming increasingly concentrated in Colombia: two thirds of coca bush cultivation took place on just 5 percent of the territory affected by such cultivation in Colombia in 2019, up from 62 percent in 2018. The overall decrease in coca bush cultivation, going hand in hand with a concentration of such cultivation, is likely the result of a number of factors. Beyond a steep increase in manual eradication since 2017, which in 2019 reached a level almost as high as that seen at its peak, in 2008, the decrease in cultivation has also been linked to successes in alternative development efforts. While in territories where no intervention was recorded the overall area under cultivation declined by 2 percent in 2019, the overall decline as compared to a year earlier amounted to 22 percent in areas where an intervention with regard to eradication and/or alternative development took place in 2019.

Despite a decrease in coca bush cultivation, greater productivity has seen cocaine manufacture in Colombia increase slightly Despite a decrease of 9 percent in the overall area under coca bush cultivation in Colombia from 2018 to 2019, the “productive” area under coca bush cultivation remained more or less stable in 2019, as previously sown fields became productive in 2019. At the same time, the concentration of coca bush cultivation in areas where yields are higher than in others meant that overall coca leaf yield continued to increase (from 4.7 tons per hectare in 2014 to 5.8 tons in 2018 and 5.9 tons in 2019). This resulted in an increase in coca leaf production, despite a decrease in the area cultivated, and thus in a small increase in the cocaine manufactured in Colombia (1.5 percent in 2019). Overall, productivity continued to increase, from an average of 6.3 kilograms of cocaine hydrochloride per harvested hectare in 2014 to 6.5 kilograms in 2018 and 6.7 kilograms in 2019; this also reflects ongoing improvements in the efficiency of cocaine-manufacturing laboratories.

Coca Cultivation in Peru

harvested coca leavesAccording to the UNODC: Coca bush cultivation in Peru has stabilized With 54,700 hectares under cultivation reported by the Peruvian authorities,10 Peru accounted for 23 percent of global coca bush cultivation in 2019. [Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), World Drug Report 2021]

Most of the areas under coca bush cultivation in Peru continued to be found in the valley of the rivers Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro (VRAEM), followed by La Convención y Lares and Inambari-Tambopata. While the area under coca bush cultivation in VRAEM and in Inambri-Tambopata continued to grow after 2013, coca bush cultivation decreased in La Convención y Lares as well as in the traditional coca-producing region of Huallaga, which only accounted for 3 percent of the national total in 2019.

After a long-term decrease in coca bush cultivation in Peru throughout the 1990s and a resurgence in the early 2000s, the area under coca bush cultivation in the country fluctuated between 40,000 hectares and 60,000 hectares in the 2010s. Since 2015, coca bush cultivation and potential production output have undergone moderate year-onyear increases, although the area under coca bush cultivation in Peru stabilized in 2019, growing by just 1 percent compared with the previous year. Inverse trends have been observed over time between the area under cultivation and eradication, although a stabilization of both cultivation and eradication was reported in 2019.

Coca Cultivation in Bolivia

According to the UNODC: Coca bush cultivation in the Bolivia increased in 2019 Following a decrease of 6 percent in the area under coca bush cultivation in the Bolivia in 2018, it grew by 10 percent in 2019 to reach 25,500 hectares. Similar to the situation in neighbouring Peru, there has been an inverse trend in the area under coca bush cultivation and eradication in the Bolivia. While rationalizationand eradication decreased bush cultivated in the traditional coca-producing area of Yungas de La Paz, this region continued to account for the most coca bush cultivation in 2019. This was followed by Trópico de Cochabamba (34 percent) and, to a much lesser extent, Norte de La Paz (2 percent). [Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), World Drug Report 2021]

“Rationalization” refers to the process of eradicating coca bush cultivation that exceeds the agreed limit of 1 cato (1,600 square meters ) per family in the coca bush-growing areas of the Bolivia. In protected areas, such as national parks, all identified coca by some 2,000 hectares in 2019, the area under coca bush cultivation grew by some 2,400 hectares. In parallel, the control exercised by coca farmers’ unions over their members, which limits the area under coca bush cultivation to 1 cato (1,600 square meters ) per family, also appears to have dwindled in 2019.

Increases in cultivation from 2018 to 2019 were reported in all three regions. Quantities of cocaine seized reached record levels in 2019 In 2019, the global quantity of cocaine seized increased by 9.6 percent compared with the preceding year to reach 1,436 tons (of varying purities), a record high. The 90 percent increase in the quantities of cocaine seized between 2009 and 2019 is likely a reflection of a combination of factors, including an increase in cocaine manufacture (50 percent between 2009 and 2019) and a subsequent increase in cocaine trafficking, as well as an increase in the efficiency of law enforcement, which may have contributed to an increase in the overall interception rate.

Some coca bush cultivation took place in areas that had been deforested in the previous year, posing a particular challenge to the country’s forest ecosystem, especially in protected areas such as the national parks of Madidi and Amboró.14 Nevertheless, with 64 percent of the coca bushes are eradicated.

Programs to Encourage Farmers Not to Grow Coca

coca eradication

n the 1990s the Department of Agricultural Reconversion in Bolivia paid farmers about $800 for every acre of coca they uprooted. The program only applied to coca grown before 1988, when planting new plots of coca was outlawed. The money was paid by a host of organizations including U.S.A.I.D. and the United Nations Drug Control Program.

Farmers who participated in the program were visited twice by a reconversion inspector who measures the plot before and after the uprooting and testified the plants have been removed. The farmer then received a check and a certificate that qualified him for alternative crop programs. Many farmers who received payments continued to grow coca. Many eradicated only part of their coca holdings, generally when coca prices were down or they were strapped for cash.

Proponents of U.S. financed programs to uproot coca plants point to fields emptied of coca bushes, growing only weeds. But on the slopes above them are vigorous healthy plants. Two-year-old plants can be pulled up hand but five year old ones are so deeply rooted you need a winch or have to cut them out. [Source: Peter White, National Geographic, January 1989]

Growing alternative crops is often easier said than done as the prices that can be earned from them is low, sometimes below the cost of production, and getting the product to market can be difficult. A crop like pineapple, which grows well in the soil and climate found in cocaine-growing regions can yield up to $30,000 a year but requires $20,000 in start up cost to plant the pineapples. Transporting oranges, bananas and yucca is prohibitively expensive. These crops often rot before they can be taken to markets. One cocaine grower told AP, "If someone can guarantee us another crop to sell, we'll rip out the coca leaf ourselves. If not, what can we do? If no one buys from us, we're going to persist with coca."

Other problems with anti-coca growing programs include a lack of manpower, resources and tactics to enforce restrictions on coca growing, which is done over a large area, often in remote valleys several days walk from the nearest road. Politicians will go along with the programs to a certain point because they like the money brought in by the programs campaigns but are reluctant to crack down too hard on coca-growers and loose their votes.

Coca Eradication Efforts in Columbia

Nick Miroff wrote in the Washington Post: U.S.-funded aerial spraying played a huge role in reducing Colombia’s coca crop from an estimated 400,000 acres in 2000 to fewer than 120,000 acres in 2012. The tactic was bitterly resented in rural communities, though, and it provided diminishing returns as drug growers moved their crops to national parks, indigenous reserves, border areas and other places off limits to spraying. [Source: Nick Miroff, Washington Post, November 10, 2015]

Eduardo Diaz, the economist and former health minister in charge of the crop substitution, told the Washington Post the government has learned critical lessons over the years about what works and does not. “It can’t be, ‘Here, try these seeds, see you later,’ ” Diaz said. “We have to establish the presence of the state in these conflict zones.”

coca harvesting in Columbia

Cash payments to individual families in exchange for voluntary eradication do not work either, Diaz said, because the possibility of earning money simply encourages everyone to grow coca. Instead, the government wants entire communities to opt for crop substitution in the hope it will bring state-building investments in infrastructure, health and education. Holdouts would face forced eradication and criminal penalties. Diaz said asking farmers to gradually phase out coca also does not work. As long as there are illegal crops in the community, there will be armed groups attracted to it, he said, like flies swarming food.

Here in Tierradentro, a tiny village in the foothills of the Nudo de Paramillo range in the northern state of Cordoba, a crop substitution program supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development is encouraging former coca growers to try bananas and cacao instead. The area is one of Colombia’s most war-torn, fought over by right-wing paramilitaries and the FARC for the past 20 years. But with a unilateral cease-fire in effect, Tierradentro is quieter now than at any time in recent memory. FARC units remain active farther up the mountain, protecting coca fields in a national park.

Farmers here say they are proud to grow food again, returning to a simpler and more innocent era. Sure, they said, the coca brought more money, but also wanton killing, prostitution and benefits that did not last. “Most of the money went to alcohol,” said Darwis Tarifa, 42, who said he lost two brothers to drug deals gone bad.

Cacao seemed the most promising alternative for Tierradentro’s farmers, but the trees planted here will take several years to bear fruit. Bananas are the only option in the meantime, and many farmers here confessed they were losing patience, earning as little as $175 a month, well below minimum wage and less than a third of what they made growing coca. Selling bricks of cocaine base was a lot easier than arranging for truckloads of bananas to reach markets several hours away along a rough dirt road. “Today we live in peace,” said Alexis Fernandez, 63. “But there’s no coca and no money.”

Farther up the mountain and a canoe ride across the muddy San Jorge River, Jacinto Tapia showed off the fields where he grew coca until switching to bananas last year. In the rich alluvial soils, his mature coca plants could be harvested every 40 days, virtually year-round, almost as good as a monthly paycheck. Soldiers arrived last year and ripped them out. Tapia signed up for the crop substitution program. “Once you start getting old, you get tired of having these problems,” said the sun-worn Tapia, 69. “You don’t make as much money, but you sleep better at night.” A few vestigial coca plants poked through the ground between the bananas and empty cans of glyphosate herbicide. Their leaves were a radiant shade of green. Tapia chopped at their roots with his machete but said the only way to finish them off was with heavy doses of the weedkiller. All it takes is a few severed roots left in the ground, he said, and the plant comes roaring back.

Coca Production in Colombia Surges as Government Makes Peace with FARC Rebels

Reporting from Tierradentro, Colombia, Nick Miroff wrote in the Washington Post: “Illegal coca cultivation is surging in Colombia, erasing one of the showcase achievements of U.S. counternarcotics policy and threatening to send a burst of cheap cocaine through the smuggling pipeline to the United States. Just two years after it ceased to be the world’s largest producer, falling behind Peru, Colombia now grows more illegal coca than Peru and third-place Bolivia combined. In 2014, Colombians planted 44 percent more coca than in 2013, and U.S. drug agents say this year’s crop is probably even larger.[Source: Nick Miroff, Washington Post, November 10, 2015]

The coca boom comes at an especially sensitive time for the Colombian government, which is in the final stages of peace negotiations with leftist FARC rebels, who have long profited from the illegal drug trade. The government has halted aerial spraying of the crop, citing concerns that the herbicides used may cause cancer. That program had been a pillar of Plan Colombia, under which the United States has provided more than $9 billion to this country since 2000.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos, a key U.S. ally, said his administration is ready to launch a massive crop substitution campaign if a deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, is reached and areas under rebel control become safe enough for government workers. The guerrillas and the government have already agreed in principle on a sweeping new development plan for Colombia’s struggling rural areas, with the FARC pledging to help persuade farmers to rip out their coca in favor of lawful crops. U.S. and Colombian officials say the biggest reason for the current bumper crop is that the FARC, along with other armed groups, has encouraged farmers to plant more coca in anticipation of the peace deal and the new government aid. Andrews said Colombia’s 2015 coca output is projected to go “way up.” Many of the plants added last year have since matured, “so what you’ll see is a big cocaine production spike as those plants come online.”

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons; DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) except coca harvesting Brookings Institute

Text Sources: “Buzzed, the Straight Facts About the Most Used and Abused Drugs from Alcohol to Ecstasy” by Cynthia Kuhn, Ph.D., Scott Swartzwelder Ph.D., Wilkie Wilson Ph.D., Duke University Medical Center (W.W. Norton, New York, 2003); National Geographic, Time, Newsweek, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, The Independent, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2022