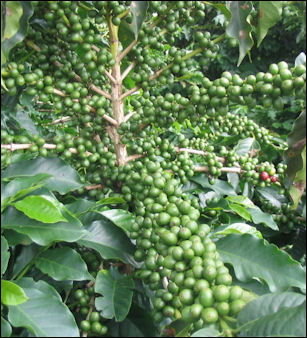

COFFEE PLANT

ripe coffee beans The coffee plant is a perennial tropical evergreen belonging to the genus “Coffea” in the family “Rubiaceae” . Although there are at least 60 plants in the genus, only three are harvested commercially: arabica, robusta and to a much lesser extent “libeca” . Hybrids have also been developed.

The coffee bean comes from the cherry or berry of the coffee plant which is actually plant’s fruit. It is produced after the withering of a white flower. Each cherry consists of two seeds (beans) surrounded by pulp and skin. The cherries are green at first and turn red when they are ripe. They take six to 14 months to ripen, depending on the species of tree.

Coffee is cultivated in many places in tropical Latin America, Asia and Africa between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. It grows best in places with rich soil, reliable rainfall and altitudes between 3000 and 6000 feet. As a rule, the higher the elevation the coffee is grown the better the quality. Cold weather and frosts can seriously damage a coffee crop. Coffee grown above 3,937 feet is considered to be the best quality.

Arabicas grow best in shady areas at elevations above 3,000 feet in climates with an average temperature between 18̊ and 25̊C the entire year, and a low of 13̊C and with rain between 40 and 90 inches a year. They are often grown on slopes of mountains or hills and shaded and protected wind damage by banana palms, orange, mango, mahogany, or rosewood trees or other large trees.

Robusta beans grow better in the open sun. They are often mass produced in plantations where they are chemically fertilized and grow fast. Robusta trees reach their peak at age 7 and can keep producing until they are 18.

Book: “Coffee: A Dark History” by Antiny Wild (W.W. Norton, 2005)

Websites and Resources: History of Coffee National Geographic National Geographic ; Coffee Research coffeeresearch.org/agriculture/coffeeplant ; International Coffee Organization ico.org/ ; Coffee Geek coffeegeek.com ; SinPari Trading: sinpari.com/Coffee_History_Cultivation.html ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Coffee Facts coffeefacts.org ; Coffee Trail guardian.co.uk/news ; Farming and Processing coffeeterms.com/coffee-farming-and-processing ;

Coffee Agriculture

coffee flower, branch and leaves

A total of 25 million farming families in 60 countries depend on coffee for their livelihood. About 70 percent of the world's coffee is grown by 7 million farmers on farms on than less than 5 hectares (12 acres) of land. Much of the work is still done by hand. Because coffee is raised on mountain sides and in forest it can not be planted and harvested with large machines like corn or wheat, which are grow on flat areas and are harvested with the entire plant being cut down. Coffee bushes take years to reach peak production, which means that growers need to make an initial investment and wait.

These days much of the world's coffee comes from high-yield robusta plants that grow well in sunny conditions. This has had a harmful effect on the environment by depriving wildlife of trees to live in. In many places subsistence farmers are being driven off their land and are being replaced by sharecroppers.

Arabicas tend to be grown on small farms. A 45-year-old third generation coffee farmer told Smithsonian magazine, “It’s a craftsman job. You’ve got to love it every day.” To produce a good quality crops, he said, requires 32 steps, including understanding the soil, choosing the right beans, cultivating plants in nurseries and giving different mixtures of compost made of coffee ground, cow manure and farm wastes to the coffee plants at different stages of their development. “When they are producing fruit, you must treat them with more respect, just as if they were a mother,” he said.

Harvesting is labor intensive work, with the cherries being picked mostly by hand. The cherries ripen at different times and are ideally picked only when they are ripe. In some places all the cherries on a plant are picked, regardless of ripeness. In other places selective picking is done. An average worker can pick 100 to 125 pounds a day.

Bourbon coffee Mechanical pickers have been invented but they offer poor results because they yields a mixture or ripe and unripe beans, Scientist are working in a genetically modified coffee with beans that stop short of ripening and then are all ripened at the same time with a chemical spray.

Problems encountered by coffee cultivators include coffee leaf rust and the berry borer, Columbia.

Biotechnology has produced decaffeinated coffee beans. Many coffee growers don’t want these plants anywhere near their plants.

In recent years there has been an effort to bring back Arabica agriculture. See Fair Trade

Coffee and the Environment

In the 1960s, most coffee was Arabicas grown in the shade of rain forest trees. Arabica coffee are relatively an environmentally-friendly crops. It was traditionally grown under a canopy of rain forest shade trees amid other kinds of vegetation. The trees and plants fixed nitrogen in the soil and their leaves provided nutrients. Few chemical were used and the lush vegetation prevented erosion and provided a habitat for wildlife. In the 1960s and 1970s Arabica crops were devastated by the coffee leaf rust.

These days much of the coffee grown are high-yield robustas that grow well in open in sunny fields and were introduced to stop the spread of coffee leaf rust.. Robusta production requires large amounts of fertilizer and pesticides and has resulted in trees being chopped down and rivers and groundwater contaminated with chemicals from pesticides and fertilizers.

Millions of hectares of rain forests and cloud forests have been clear. Much of the land in the 25 highly threatened biodiversity hot spots designated by Conservation International are in or around coffee-growing areas. One study found that coffee plantations located near fragments of forests boosted their income because of the presence of pollinating bees.

The coffee genome was cracked after two years at an expense of $2 million. The Nara Institute of Science and Technology in Japan has developed genetically-engineered plants that produce coffee beans with 60 percent less caffeine. Many coffee growers don’t want these plants anywhere near their plants.

Coffee Processing in Producing Countries

Handmaking coffee in Indonesia Coffee processing is also very labor intensive. Great attention and care is requires during the fermenting, washing and drying process. A few over-fermented beans can spoil the whole bunch.

After the harvest, cherries are dried in the sun until they turn hard and brown. The beans are regularly raked so that the drying is uniform. In the processing plant, the hull, skin and pulp of the fruit are rubbed from the bean by a noisy hulling machine Try to avoid cheap hotels near a coffee processing plant. These factories often operate between 11:00pm and dawn because that is when electricity is at its cheapest.

In places where water is plentiful beans are removed using the wet method, in which the cherries are passed through rollers that squeeze the beans out. The beans are then placed in vats so the pulp ferments away. Finally the beans are dried to remove the skin around the bean.

After the beans have been dried and hulled they are often cured and then sorted for size with special machines. They are then graded according to size, shape, aroma, appearance, and imperfections and rated according to the flavor they will produce: mild or harsh, pungent or neutral, bitter or mellow. High qualify coffees are often hand sorted by nimble-fingered workers. After this beans, called "green coffee," are usually shipped to consuming countries.

Coffee Processing in Consuming Countries

In the coffee consuming countries, the beans are blended, roasted, ground and packaged for sale. Before it is roasted coffee is mostly sold and distributed in 60 kilogram (132-pond) bags. For decaffeinated coffee, the green beans are soaked in poisonous solvents, carbon dioxide and repeatedly bathed in water to remove the caffeine.

Mechanical separator Most coffees are blends although in recent years coffees from a particular region or of a particular type have become popular. Decisions about beans blend are made by professional coffee tasters, which can tell the quality, place of origin and altitude grown by sniffing the beans or sipping a cup made from them. Describing one at work, Tony Smith wrote in the New York Times, “Luiz Norberti Paschoal removes the frothy top off one last cup of espresso with a theatrical slurp. Savoring the taste and aroma for a few seconds, he then expels the liquid in a thick brown jet into a bucket at his feet.”

Once a blend has been selected the beans are roasted in a perforated cylindrical machine that circulates hot air at a temperature between 300̊F and 425̊F for 16 to 17 minutes. Roasting brings out the flavor and aroma of coffee. Some people believe slow roasting is best. Others argue quick roasting is better.

Coffees are classified according to the darkness of the roasted bean. Dark roasts create sweet, toasty flavors. Light roast are popular in the United States. After roasting most blended coffees ground with roller mills.

Coffee Business

Coffee is the world's largest traded commodity after crude oil and creates jobs for 10 millions people, many of them in poor countries. Global revenues from coffee sales are around $55 billion, compared to $30 billion in the 1990s. Coffee is sold on the world market at commodity exchanges along with other agricultural products. The benchmark robusta beans price per ton is the standard price for coffee. The coffee futures market is popular with speculators.

The coffee market is controlled by the four big coffee roasters: Sara Lee, Nestle, Proctor & Gamble and Kraft. Market share in 2002: Philip Morris (25 percent); Nestle (24 percent); Sara Lee (7 percent), Proctor & Gamble (7 percent), Tchibo (6 percent); Other (31 percent). Starbucks only accounts for 1 percent of all coffee sales.

About 10 percent of the profits from coffee sales go to growers; 10 percent to exporters, 55 percent to shippers and roasters and 25 percent to retailers. In early 1990s, people in the coffee-producing countries earned about 40 cents on every dollar spent on coffee. Now they only earn about 8 to 13 cents. The difference is attributed mainly to low coffee prices paid to farmers and the high prices paid by consumers.

coffee dryingIn 2002, a typical small farmer sold his crop to a middleman at a price of 14 cents a kilogram. After the middleman takes the raw coffee berries it to a mill and transports the beans to a major trading center or city he sells them for 26 cents a kilogram to an exporter, who transports the coffee to a port, sorts it for quality, pays taxes and delivers to an importer, who buys it for 45 cents a kilogram. He delivers it to a consuming country in Europe or North America and sells it there for 52 cents a kilo. The price includes the cost of the coffee, insurance and freight. Transportation to a roaster adds 11 cents and boosts the price to 63 cents. [Source: The Independent]

At the roasting factory, the coffee beans lose weight as the are ground and processed into brewing coffee or instant coffee. In the case of instant coffee, a kilogram of coffee that was bought for 63 cents is reduced in weight to 385 grams and sells for $1.64. The roaster processes, packages, distributes and markets the coffee and sells it a wholesale price to supermarkets for around $13.40 a kilo. Consumers but it at the retail price of $26.40 a kilogram, or 7000 percent more than what the farmer is paid.

For a $3.75 double cappuccino sold at a coffee specialty shop in the United States, 3.5 cents goes to coffee growers, 17.5 cents goes to coffee millers, exporters, importers and roasters, 40 cents covers the cost of the milk, 7 cents covers the cost of the cup, $1.35 pays the labor costs at the coffee shop, $1.29 covers the shop rent, marketing and general administration, 18 cents goes towards the initial investment, and 25 cents is the profit earned by the shop owner.

Rising demand for coffee in China has created rising demand for coffee production world wide. Starbucks buys about 2 percent of the world’s coffee.

Coffee Prices

Coffee has traditionally been a relatively lucrative crop. The price for hectare of coffee in 2000 was $2,250, compared to $421 for cocoa. The prices however are highly unstable, with the fortunes of coffee growers rising and falling with the wildly fluctuating world prices of coffee. Coffee prices are effected by weather, politics and speculation on coffee futures, with big rises or falls sometimes determined by whether or not there is a winter frost in Brazil.

Prices were once largely controlled by the International Coffee Organization (ICO), which had traditionally been dominated by the United States which tried to keep prices stable to avoid political unrest in Latin America. Pricing was kept in line in accordance with the 1962 International Coffee Agreement (ICA) between coffee-consuming nations and coffee-producing nations set to a system of quotas designed to keep prices high by preventing overproduction.

Prices remained relatively stable until 1989 when the ICA collapsed and United States withdrew its support from the ICO and let the market control the price. The result was more instability and lower prices.

Volatile Coffee Prices in the 1990s and 2000s

Coffee fermentation bins In the 1990s supply began exceeding demand and price began to plummet. By 1997 the wholesale price of coffee was 38 percent lower than it was 1989. By 2001, the price of a bound of coffee had dropped to 50 cents a pound half what it was two year before.

Low prices have been the rule through the 1990s and 2000s. The only time they rose significantly were in 1994 and 1997 when frost ruined much of the coffee crop in Brazil.

In 2000, coffee prices fell as low as 60 cents a pound, below production costs. The value of exports fell to $5 billion, down from $12 billion in 1996. Prices then fell too 42 cents a pound in 2001. Prices didn’t start rebounding until around 2006 and then producers were warned not to boost production and cause prices to collapse again.

In 2006 prices were about 90 cents a pound and reached a six year high in July 2006. The rise was attributed in part efforts by the coffee industry and the governments in Brazil urging their citizens to buy more of the drink, resulting in a doubling consumption there. Similar campaigns are being launched in India, Indonesia and Mexico. Coffee producers there hope the campaign will have the same impact as the one in Brazil.

In 2007 the price was $1.05 a pound Coffee prices rose in late 2007 and early 2008 and then reached record lows in the forth quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009 during the global financial crisis.

Coffee Prices and Vietnam

Many blamed the overproduction and the collapse of prices in the 1990s and early 2000s on Vietnam. Between 1990 and 2000 over a million acres of robusta were planted in Vietnam, increasing its annual coffee production from 84,000 tons in 1991 to 950,000 tons in 2002. Practically overnight Vietnam rose from being a minor player in the world coffee market to a major player, and overtook Columbia as the world’s No. 2 producer. Their exports flooded the market with coffee as Brazil was boosting it production in Brazil, resulting in oversupply and declining prices.

Vietnam has demonstrated how coffee prices and coffee farmers can be dramatically affected by globalization and decisions made by major financial institutions. The program to boost coffee production Vietnam was largely the idea of the World Bank. In the early 1990s, Vietnam was facing an export crisis so the World Bank designed a $96 million rescue plan that revolved around generating foreign currency by growing and exporting coffee.

Impact of High Coffee Prices

Separation vats Low coffee prices are good for coffee makers and bad farmers After the collapse of prices in 2000 and 2001 Starbucks and Nestle made record profits over $1 billion each. In some cases they boosted their profits margins to 26 percent because they were able to charge the same prices for their products while their cost were sharply reduced by the low coffee prices.

In the mean time farmers in the developing world are getting a pittance for their crops. In the worst cases their production costs were higher than the money they received from their buyers. Many had a hard time feeding their families and sending their children to school. In some places they were forced abandon their land, move to the cities or grow coca instead.

The low prices have also caused the quality of coffee to fall. Farmer see little point in lavishing much care on their coffee plants if they aren’t going to make any money from them Producers have replaced high-quality arabica beans with cheaper low-quality robusta beans. Supermarket consumers sometimes complain their purchases contain materials “not recognizable as coffee.”

Combating High Coffee Prices

As of 2002, supply exceeded demand by about 8 percent and was increasing at a rate of 2 percent a year while the rate of increase for demand was only 1.5 percent. Of the 115 million sacks of coffee reaped from the 2001-02 harvest, only 105 million were consumed. Some 50 million sacks are stored away in warehouses. In Central America, an estimated 600,000 coffee workers lost their part time or full time jobs.

Some large growers and producers are responding to challenge by improving the quality of their coffee, marketing it as specialty coffee, and charging higher prices. Other are looking into new ways to use coffee. In Japan and Columbia researchers studied the use of coffee for roofing and wall material In Costa Rica, coffee was burned as an alternative energy source. In an effort to raise prices in 2001, many of producing countries in Latin America agreed to earmarked 5 percent of the lowest grade coffee for purposes other than consumption.

Coffee growers have prosed establishing an OPEC-like cartel called the Association of Coffee Producers to lower production and raise prices. The plan has gotten very far. Coffee is not a critical as oil so producers don’t have as much leverage and coffee-producing nations had difficulty agreeing on terms.

Another solution is destroy the five million sacks of low quality coffee in warehouses in coffee-producing countries. The cost of that would be $100 million but, experts believe, would cause prices to rise by 20 percent.

Fair Trade and ECO-O.K. Coffees

These days many companies have begun promoting "ECO-O.K." coffees whose designation is based on the amount of shade trees used to grow the coffee, respect for the rain forest, the use of fertilizers and pesticides, wages given to peasants and the environmental-soundness of the mills. Few growers score A+'s in all categories but those that meet most of them get the "ECO-O.K" designation. Only about a sixth of the coffee consumed by Americans is grown organically in the shade.

roasting grades

Fair Trade is a network of North American and European activist who act as middle men and pay coffee growers higher than market prices for their crops and sell the beans to companies that sell their products at supermarkets with a " Fair Trade" label for $2 more than regular coffee. Under the coffee industry’s Fair Trade protocol, farmers in 2003 were paid $1.26 a pound for beans, more double the current average price of 52 cents a pound for green coffee. Farmers who grow coffee for Fair-Trade- certified coops say their income has doubled.

Procter & Gamble sells a premium coffee called Millstone that has been certified by the protocol. Starbucks and Wall-Mart also sell Fair Trade coffees. As of 2004, Fair Trade coffee made up only 0.5 percent of the total coffee market. About 35 to 45 percent of the Fair Trade coffee sold in the United States is sold at Fair Trade prices. The rest is sold at market value in regular coffee.

Pauk Katzeff, a buddy of Hunter Thompson, is the leader of a movement to encourage farmers to grow high quality arabica beans. The idea is that high quality coffee will bring in higher prices, helping the farmer, and protect the environment and rain forest by encouraging farmers to raise arabica beans that grow better shaded by other trees than cheap robusta beans that do better in open sun.

Groups such as Oxfam are trying to pressure the four big coffee roasters—Sara Lee, Nestle, Proctor & Gamble and Kraft — into guaranteeing that farmers get paid more than their production costs.

There is also a movement to produce organic coffee. Organic coffees have only a 1 percent share of the market and some think the idea is a dead end because people “don’t want to think about their health when they drink coffee.”

coffee selling

World’s Top Coffee Producing Countries

Coffee production is measured in bags, with one bag being equal to 60 kilograms. The Largest coffee producers are 1) Brazil; 2) Vietnam and 3) Columbia: They are big enough that they can determine the market price. Brazil produces roughly 30 percent of the world’s coffee. There is saying in the coffee trade that when Brazil sneezes everything catches a cold. In 1994, a winter frost killed much of the crop in Brazil, causing prices to shoot up to $2 a pound. Speculators in the futures market pushed up prices three times that year. Coffee production in 2006 was around 120 million bags with 41.5 million bags from Brazil. That year coffee stockpiles dropped to their lowest level since 1976, with stocks sufficient to cover only three months of consumption.

World’s Top Producers of Coffee, Green (2020): 1) Brazil: 3700231 tonnes; 2) Vietnam: 1763476 tonnes; 3) Colombia: 833400 tonnes; 4) Indonesia: 773409 tonnes; 5) Ethiopia: 584790 tonnes; 6) Peru: 376725 tonnes; 7) Honduras: 364552 tonnes; 8) India: 298000 tonnes; 9) Uganda: 290668 tonnes; 10) Guatemala: 225000 tonnes; 11) Laos: 185721 tonnes; 12) Mexico: 175555 tonnes; 13) Nicaragua: 158759 tonnes; 14) China: 114000 tonnes; 15) Costa Rica: 76008 tonnes; 16) Tanzania: 60651 tonnes; 17) Philippines: 60641 tonnes; 18) Cote d’Ivoire: 59412 tonnes; 19) Venezuela: 57100 tonnes; 20) Madagascar: 42220 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org. A tonne (or metric ton) is a metric unit of mass equivalent to 1,000 kilograms (kgs) or 2,204.6 pounds (lbs). A ton is an imperial unit of mass equivalent to 1,016.047 kg or 2,240 lbs.]

World’s Top Producers (in terms of value) of Coffee, Green (2019): 1) Brazil: Int.$6288668,000 ; 2) Vietnam: Int.$3518950,000 ; 3) Colombia: Int.$1849612,000 ; 4) Indonesia: Int.$1590164,000 ; 5) Ethiopia: Int.$1008395,000 ; 6) Honduras: Int.$995406,000 ; 7) Peru: Int.$759160,000 ; 8) India: Int.$667651,000 ; 9) Uganda: Int.$530961,000 ; 10) Guatemala: Int.$470177,000 ; 11) Nicaragua: Int.$363603,000 ; 12) Laos: Int.$346652,000 ; 13) Mexico: Int.$346284,000 ; 14) China: Int.$250761,000 ; 15) Costa Rica: Int.$175733,000 ; 16) Cote d’Ivoire: Int.$141465,000 ; 17) Madagascar: Int.$137417,000 ; 18) Philippines: Int.$125472,000 ; 19) Venezuela: Int.$118503,000 ; [An international dollar (Int.$) buys a comparable amount of goods in the cited country that a U.S. dollar would buy in the United States.]

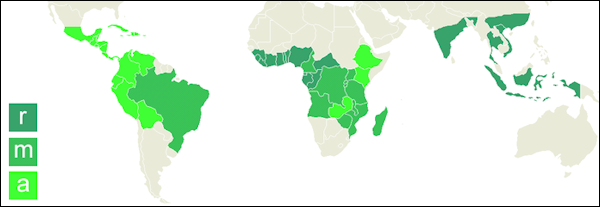

robusta (r) and arabica (a) producers

Top Producing Countries of Green Coffee: in 2008 (Production, $1000; Production, metric tons, FAO): 1) Brazil, 2286655 , 2796927; 2) Viet Nam, 872663 , 1067400; 3) Colombia, 563037 , 688680; 4) Indonesia, 558342 , 682938; 5) Peru, 223831 , 273780; 6) Ethiopia, 223520 , 273400; 7) Mexico, 217321 , 265817; 8) India, 214200 , 262000; 9) Guatemala, 203256 , 248614; 10) Uganda, 173098 , 211726; 11) Honduras, 155448 , 190137; 12) Costa Rica, 87757 , 107341; 13) Philippines, 79653 , 97428; 14) El Salvador, 73417 , 89801; 15) Côte d'Ivoire, 65404 , 80000; 16) Papua New Guinea, 61644 , 75400; 17) Nicaragua, 59458 , 72727; 18) Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), 58864 , 72000; 19) Madagascar, 54776 , 67000; 20) Thailand, 41239 , 50442;

Top Producing Countries of Green Coffee: (Production, $1000; Production, metric tons in 2008, FAO): 1) Brazil, 2286655 , 2796927; 2) Viet Nam, 872663 , 1067400; 3) Colombia, 563037 , 688680; 4) Indonesia, 558342 , 682938; 5) Peru, 223831 , 273780; 6) Ethiopia, 223520 , 273400; 7) Mexico, 217321 , 265817; 8) India, 214200 , 262000; 9) Guatemala, 203256 , 248614; 10) Uganda, 173098 , 211726; 11) Honduras, 155448 , 190137; 12) Costa Rica, 87757 , 107341; 13) Philippines, 79653 , 97428; 14) El Salvador, 73417 , 89801; 15) Côte d'Ivoire, 65404 , 80000; 16) Papua New Guinea, 61644 , 75400; 17) Nicaragua, 59458 , 72727; 18) Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), 58864 , 72000; 19) Madagascar, 54776 , 67000; 20) Thailand, 41239 , 50442;

World’s Top Coffee Exporting Countries

World’s Top Exporters of Coffee, Green (2020): 1) Brazil: 2372633 tonnes; 2) Vietnam: 1231314 tonnes; 3) Colombia: 694928 tonnes; 4) Indonesia: 375671 tonnes; 5) Honduras: 363400 tonnes; 6) Germany: 340060 tonnes; 7) Uganda: 329373 tonnes; 8) Belgium: 241340 tonnes; 9) Ethiopia: 230246 tonnes; 10) Peru: 213236 tonnes; 11) India: 205809 tonnes; 12) Guatemala: 189489 tonnes; 13) Nicaragua: 149117 tonnes; 14) Mexico: 100767 tonnes; 15) Costa Rica: 69654 tonnes; 16) Tanzania: 57641 tonnes; 17) Laos: 50620 tonnes; 18) China: 49169 tonnes; 19) Kenya: 43386 tonnes; 20) Cote d’Ivoire: 40263 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

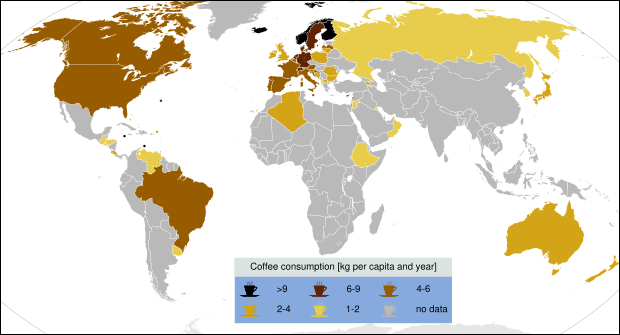

Coffee consumption map

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Coffee, Green (2020): 1) Brazil: US$4973728,000; 2) Colombia: US$2453943,000; 3) Vietnam: US$1943554,000; 4) Honduras: US$980247,000; 5) Germany: US$972497,000; 6) Indonesia: US$809679,000; 7) Ethiopia: US$742823,000; 8) Guatemala: US$651964,000; 9) Peru: US$639931,000; 10) Belgium: US$617996,000; 11) Uganda: US$514192,000; 12) India: US$461672,000; 13) Nicaragua: US$438202,000; 14) Mexico: US$355653,000; 15) Costa Rica: US$325620,000; 16) Kenya: US$208991,000; 17) United States: US$148656,000; 18) Tanzania: US$129215,000; 19) China: US$123557,000; 20) Papua New Guinea: US$115163,000

World’s Top Roasted Coffee Exporting Countries

World’s Top Exporters of Roasted Coffee (2020): 1) Germany: 245626 tonnes; 2) Italy: 239579 tonnes; 3) Netherlands: 98949 tonnes; 4) Switzerland: 95858 tonnes; 5) United States: 79771 tonnes; 6) Poland: 61676 tonnes; 7) France: 58030 tonnes; 8) Canada: 43412 tonnes; 9) Belgium: 35887 tonnes; 10) United Kingdom: 28626 tonnes; 11) Slovakia: 25429 tonnes; 12) Czechia: 22823 tonnes; 13) Sweden: 22764 tonnes; 14) Spain: 21479 tonnes; 15) Bulgaria: 17623 tonnes; 16) Malaysia: 14878 tonnes; 17) Portugal: 13321 tonnes; 18) Colombia: 11268 tonnes; 19) Russia: 11101 tonnes; 20) Austria: 9935 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Roasted Coffee (2020): 1) Switzerland: US$2846297,000; 2) Italy: US$1639310,000; 3) Germany: US$1601323,000; 4) France: US$1378781,000; 5) Netherlands: US$724673,000; 6) United States: US$632450,000; 7) Canada: US$386205,000; 8) Poland: US$340117,000; 9) United Kingdom: US$300565,000; 10) Belgium: US$277666,000; 11) Spain: US$188459,000; 12) Czechia: US$167253,000; 13) Sweden: US$135564,000; 14) Slovakia: US$133408,000; 15) Portugal: US$92526,000; 16) Bulgaria: US$90034,000; 17) Austria: US$75687,000; 18) Colombia: US$68787,000; 19) Lithuania: US$58624,000; 20) Denmark: US$57588,000

Coffee plantation

Coffee Consumers

Tea is more popular than coffee almost everywhere in the world except the United States.

The top five coffee drinkers are (cups per day): 1) Finland (3.4), 2) Germany (2 cups), 3) France (1.5 cups), 4) Italians (1.4 cups) and 5) Americans (1.1 cups).

The worlds top consumers of coffee are (1988): 1) the U.S. 2) Brazil, 3) W. Germany, 4) France, 5) Japan, 6) Italy, 7) the Netherlands, 8) Spain, 9), Columbia, 10) the UK.

The United States is the world’s largest coffee consumer. It consumes about a quarter of the world’s coffee, importing 75 percent from other countries sin the Americas. Daily coffee consumption in the United States rose from 49 percent in 2004 to 57 percent in 2007.

World’s Top Coffee Importing Countries

World’s Top Importers of Coffee, Green (2020): 1) United States: 1427849 tonnes; 2) Germany: 1120426 tonnes; 3) Italy: 566783 tonnes; 4) Japan: 391611 tonnes; 5) Spain: 317417 tonnes; 6) Belgium: 314423 tonnes; 7) France: 234313 tonnes; 8) Russia: 198323 tonnes; 9) Switzerland: 191822 tonnes; 10) Netherlands: 189184 tonnes; 11) Canada: 188997 tonnes; 12) United Kingdom: 162380 tonnes; 13) South Korea: 159748 tonnes; 14) Poland: 128713 tonnes; 15) Sweden: 109759 tonnes; 16) Malaysia: 104640 tonnes; 17) Australia: 90626 tonnes; 18) Algeria: 82517 tonnes; 19) Turkey: 79071 tonnes; 20) India: 77584 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

Immature coffee beansWorld’s Top Importers (in value terms) of Coffee, Green (2020): 1) United States: US$4543041,000; 2) Germany: US$2762952,000; 3) Italy: US$1234563,000; 4) Japan: US$1061674,000; 5) Belgium: US$765896,000; 6) Switzerland: US$717986,000; 7) France: US$638308,000; 8) Spain: US$633487,000; 9) Canada: US$618367,000; 10) Netherlands: US$509858,000; 11) South Korea: US$467795,000; 12) United Kingdom: US$446258,000; 13) Russia: US$416436,000; 14) Sweden: US$326675,000; 15) Poland: US$292511,000; 16) Australia: US$280208,000; 17) Malaysia: US$223257,000; 18) Finland: US$193614,000; 19) Saudi Arabia: US$173993,000; 20) Turkey: US$165783,000

World’s Top Importers of Coffee Extracts (2020): 1) Philippines: 166151 tonnes; 2) United States: 69991 tonnes; 3) Germany: 64817 tonnes; 4) Russia: 62167 tonnes; 5) United Kingdom: 41686 tonnes; 6) China: 40279 tonnes; 7) Canada: 36634 tonnes; 8) Poland: 35580 tonnes; 9) United Arab Emirates: 28139 tonnes; 10) France: 26787 tonnes; 11) Turkey: 23818 tonnes; 12) Japan: 23765 tonnes; 13) Saudi Arabia: 22677 tonnes; 14) South Africa: 22641 tonnes; 15) Malaysia: 21700 tonnes; 16) Netherlands: 20268 tonnes; 17) Singapore: 19962 tonnes; 18) Czechia: 19312 tonnes; 19) Hungary: 18501 tonnes; 20) Ukraine: 18179 tonnes

World’s Top Importers (in value terms) of Coffee Extracts (2020): 1) Philippines: US$521852,000; 2) United States: US$499656,000; 3) Germany: US$443894,000; 4) Russia: US$385688,000; 5) United Kingdom: US$328237,000; 6) Poland: US$268423,000; 7) China: US$232588,000; 8) France: US$212506,000; 9) Canada: US$166467,000; 10) Japan: US$164166,000; 11) Australia: US$149662,000; 12) Netherlands: US$148193,000; 13) Saudi Arabia: US$141039,000; 14) Turkey: US$134672,000; 15) Czechia: US$134048,000; 16) United Arab Emirates: US$131174,000; 17) Ukraine: US$123969,000; 18) South Korea: US$116370,000; 19) Thailand: US$114430,000; 20) Malaysia: US$104600,000

World’s Top Roasted Coffee Importing Countries

coffee plants

World’s Top Importers of Roasted Coffee (2020): 1) France: 151048 tonnes; 2) United States: 97226 tonnes; 3) Germany: 93904 tonnes; 4) Netherlands: 72196 tonnes; 5) Canada: 67418 tonnes; 6) United Kingdom: 66789 tonnes; 7) Poland: 59132 tonnes; 8) Austria: 46994 tonnes; 9) Romania: 39428 tonnes; 10) Belgium: 37335 tonnes; 11) Czechia: 33691 tonnes; 12) Russia: 32376 tonnes; 13) Spain: 27128 tonnes; 14) Slovakia: 26322 tonnes; 15) Ukraine: 23624 tonnes; 16) Denmark: 21473 tonnes; 17) Italy: 21344 tonnes; 18) Hungary: 19907 tonnes; 19) Lithuania: 18063 tonnes; 20) South Korea: 16796 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Importers (in value terms) of Roasted Coffee (2020): 1) France: US$2236184,000; 2) United States: US$1133225,000; 3) Germany: US$780182,000; 4) Netherlands: US$675142,000; 5) Canada: US$589873,000; 6) United Kingdom: US$543116,000; 7) Austria: US$380061,000; 8) Spain: US$376848,000; 9) Belgium: US$354253,000; 10) Poland: US$353932,000; 11) South Korea: US$269994,000; 12) Italy: US$263194,000; 13) Russia: US$234922,000; 14) Romania: US$220274,000; 15) Australia: US$215571,000; 16) Czechia: US$208981,000; 17) Portugal: US$154928,000; 18) China: US$154787,000; 19) Switzerland: US$137020,000; 20) Greece: US$130810,000

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2022