LIVESTOCK

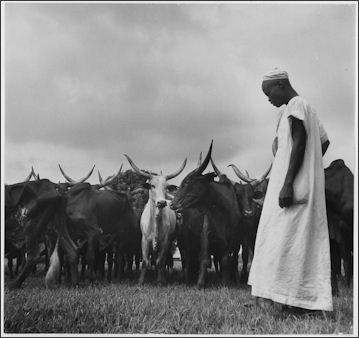

cattle in French Equatorial Africa Large animals such as horses, water buffalo, oxen and cattle are used in farming, particularly for plowing; are kept for wealth; and used as beasts of burden and sources of meat. Small livestock such as goats, pigs and sheep reproduce quickly and are sold for money, slaughtered for meat and raised for milk, skins and wool. Chickens, ducks and other fowl produce eggs and meat. Many of these animals are also used in sacrifices and rituals.

Villagers like to own their own plowing animals. It is difficult to borrow or share animals because often farmers want to plow and perform other chores with them at around the same time. Pigs, goats and chickens are generally allowed to roam free around the village. They sometimes roam around inside huts where people live. Development officials try to discourage this as a precaution against disease.

Modern domesticated animals are the way the are because of selecting breeding, which essentially means to take animals with traits you want and breed them and in the next generation you repeat the process until the traits become dominate.

Large numbers of animals are raised by herders and nomads. Herders direct their animals with shouts, well aimed rocks, whistles, clicks and noises made by hitting the roof of the mouth with the tongue. Sometimes they use dogs, which are useful in herding animals and scaring off potential predators.

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY DOMESTICATED ANIMALS factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST CATTLE AND COW DOMESTICATION factsanddetails.com ;

CATTLE: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND MEAT factsanddetails.com ;

PIGS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, PRODUCERS AND PORK-EATING CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com ;

GOATS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, MILK AND MEAT factsanddetails.com ;

DONKEYS, MULES AND ONAGERS: THEIR HISTORY, USES AND BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

What Does Animal Domestication Mean

Katja Pettinen wrote in Woman’s World: Domesticated animals is a category that includes the many species that humans consume as food: cows, chickens, sheep, reindeer, and the rest. Most animals that have been domesticated are there to fulfill some kind of functional relationship for humans: to provide us with calories, hides, or wool, or as a means of transportation. That’s not to say that humans don’t develop close feelings for some of these species, such as horses. In each category, though, these species are there to perform tasks. [Source: Katja Pettinen, Woman’s World,, April 18, 2023]

For biologists, who commonly wrestle with issues of classification, the term “domesticated” means that there is a clear physical difference between a species in the wild and its domesticated counterpart. Since Charles Darwin began to write about this in the 1800s, that difference has been dubbed the “domestication syndrome.” In part, the term “syndrome” here highlights the fact that the domesticated forms no longer can sustain themselves in the wild. Instead, the new variant of the species — the domesticated version — is dependent on humans. This change results from “artificial selection” rather than natural selection, operating in nature. Through artificial selection, humans now increasingly control three main aspects of animals’ lives: food, shelter, and reproduction.

It’s clear that many things become altered if you keep an animal captive. Some of the changes come about because, in contrast to life in the wild, animals in captivity no longer go out and acquire their own food. Nor do captive animals traverse the same amount of territory as their wild forebears. This decline in movement changes the body on multiple levels. Pretty quickly, it becomes a loop: The less you move, the less you can move. So all in all, domesticated animals become increasingly dependent on humans. Once this pattern is repeated over many generations, the changes become encoded in the biology of these animals, and a new, fully domesticated species comes into existence.

Artiodactyls (Even-Toed Ungulates)

Most domesticated animals are artiodactyls. Artiodactyls are the most diverse, large, terrestrial mammals alive today. According to Animal Diversity Web: They are the fifth largest order of mammals, consisting of 10 families, 80 genera, and approximately 210 species. As would be expected in such a diverse group, artiodactyls exhibit exceptional variation in body size and structure. Body mass ranges from 4000 kilograms in hippos to two kilograms in lesser Malay mouse deer. Height ranges from five meters in giraffes to 23 centimeters in lesser Malay mouse deer. [Source: Erika Etnyre; Jenna Lande; Alison Mckenna; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Artiodactyls are paraxonic, that is, the plane of symmetry of each foot passes between the third and fourth digits. In all species, the number of digits is reduced by the loss of the first digit (i.e., thumb), and many species have second and fifth digits that are reduced in size. The third and fourth digits, however, remain large and bear weight in all artiodactyls. This pattern has earned them their name, Artiodactyla, which means "even-toed". In contrast, the plane of symmetry in perissodactyls (i.e., odd-toed ungulates) runs down the third toe. The most extreme toe reduction in artiodactyls, living or extinct, can be seen in antelope and deer, which have just two functional (weight-bearing) digits on each foot. In these animals, the third and fourth metapodials fuse, partially or completely, to form a single bone called a cannon bone. In the hind limb of these species, the bones of the ankle are also reduced in number, and the astragalus becomes the main weight-bearing bone. These traits are probably adaptations for running fast and efficiently. /=\

Artiodactyls are divided into three suborders. 1) Suiformes includes the suids, tayassuids and hippos, including a number of extinct families. These animals do not ruminate (chew their cud) and their stomachs may be simple and one-chambered or have up to three chambers. Their feet are usually 4-toed (but at least slightly paraxonic). They have bunodont cheek teeth, and canines are present and tusk-like. 2) The suborder Tylopoda contains a single living family, Camelidae. Modern tylopods have a 3-chambered, ruminating stomach. Their third and fourth metapodials are fused near the body but separate distally, forming a Y-shaped cannon bone. The navicular and cuboid bones of the ankle are not fused, a primitive condition that separates tylopods from the third suborder, Ruminantia. 3) This last suborder includes the families Tragulidae, Giraffidae, Cervidae, Moschidae, Antilocapridae, and Bovidae, as well as a number of extinct groups. In addition to having fused naviculars and cuboids, this suborder is characterized by a series of traits including missing upper incisors, often (but not always) reduced or absent upper canines, selenodont cheek teeth, a three or 4-chambered stomach, and third and fourth metapodials that are often partially or completely fused. /=\

See Separate Article: ARTIODACTYLS (EVEN-TOED UNGULATES): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Humans Have Shared Food With Animals for Millennia — Why?

James Gorman wrote in the New York Times: “Throughout history in fat years and lean across many cultures, sometimes with no apparent reason, humans have fed animals of every imaginable stripe in every imaginable way. Some researchers think the desire to give food to other animals may drive domestication as much as the human desire to eat them does. Our Stone Age leftovers from the hunt may have fostered the domestication of dogs. Some of us give our beloved dead to vultures, which is a problem when the birds disappear. We fed and feed cats both tame and feral, sharks, alligators, deer, hedgehogs, bears, pigeons of all sorts, ducks, swans, zoo animals, lab animals, pets, farm animals and more. [Source: James Gorman, New York Times, May 12, 2021]

A group of researchers in Britain is asking: Where does this desire to give food to other animals come from, and what has it meant for animals, humans and their shared environments? Some feeding of animals is purely practical. You feed chickens today if you want to eat their eggs, or their wings, tomorrow. You can’t ride a starving horse. Animals used for experiments in laboratories have to be kept alive to get cancer.

“But a lot of feeding is unrelated to any return on investment. The black kites of Delhi reach population densities that may be the highest for raptors anywhere because of accidental and purposeful feeding. They rely on garbage and on the tasty and nutritious pests that garbage attracts. And they also benefit from the charity of Muslims who follow a tradition of tossing bits of meat into the air for the birds.

Rabari herder with animals “Many Indians feed street dogs as a matter of course, treating them as animal neighbors. In a small city near Ahmedabad where I reported on anti-rabies efforts, residents told me that you can’t just give dogs plain leftover bread. You have to put some clarified butter on it, to make it palatable. The residents were middle class, and had both bread and butter to give, but I also met people who lived by the side of the road, with nothing more than mattresses and a few pots, who shared their food with dogs.

“Almost nothing about humans feeding animals is fully understood, largely because scholars have not given the subject a great deal of attention. And that, most of all, is what the researchers in England and Scotland want to change. With a four-year grant of more than $2 million from the Wellcome Trust, five researchers are pursuing a collaborative multidisciplinary attempt to give animal feeding its due, and begin to answer some puzzling questions. They call their project, “From ‘Feed the Birds’ to ‘Do Not Feed the Animals.’”

“Naomi Sykes, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter, is the moving force behind the project. She is working with Stuart Black, a geochemist at the University of Reading; and Andrew Kitchener, principal curator of vertebrates at National Museums Scotland. Black and Sykes have also been looking at changes in wildcats in Britain and their diet over time, and studying the bones of wild squirrels that were fed peanuts to help keep the population going. In adapting to the diet, the squirrels may not have developed the same jaw muscles as squirrels that have to struggle with pine cones, he said. Adaptations to changing diets for animals that live around or near humans can result in significant skeletal changes, he said, which raises questions about some physical changes that are thought to accompany domestication in different animals. Animals might have adapted to living around humans long before they became what we think of as domesticated. “So did the change come before they were domesticated or did the change come because they were domesticated?” he asked.

Domestication, Extinction and Humans Sharing Food With Animals

James Gorman wrote in the New York Times: One striking possible answer to why humans have feed animals is extinction. Domestication may be the death knell for wild progenitors. The ancestors of horses and cattle are gone. And while there are still wolves around, they are not thriving the way dogs are. [Source: James Gorman, New York Times, May 12, 2021]

Sykes’s group has largely restrict itself to the last 2,000 years, but Black said some detours are irresistible, like the Tomb of the Eagles, a 5,000-year-old stone-age site in the Orkney Islands known officially as the Ibister Chambered Cairn. The cairn, or tomb, held about 16,000 human bones, and the remains of about 30 white-tailed sea eagles, Black said. “They were deposited over quite a significant period of time,” he said, “so it was people coming back, putting eagle remains in there....The key question that nobody has really answered at the moment is whether people went out and killed and then deposited them as a sort of an offering. There is a suggestion that they may have been pets.” If that were the case, the eagles would have probably been eating a different diet than wild eagles that were foraging at sea.

Gaucho in Patagonia “Sykes sees much of the human habit of feeding animals in the light of domestication, which she says happened as much through the process of humans feeding animals as it did through catching and corralling them to eat. That seems clear enough with our close companions, dogs and cats. “It also seems that some animals that we now eat, like chickens and rabbits, may have first come into our lives not as food, but as eaters. And, she said, “domestication is not this thing that happened way back when, in this kind of neolithic moment where everybody got together and goes, we’re going to domesticate animals. I just don’t buy it. I think it’s something that has not only continued throughout time, but it’s really accelerating.”

“Bird feeding is just one example, and that sets off warning bells for her, because domestication and extinction often go together even if the cause and effect isn’t clear. The aurochs gave way to cattle. There are plenty of domestic cats in Britain, but just a few Scottish wildcats. Wolves are still here but not the wolves that dogs descended from. They are extinct. And modern wolves are just hanging on, while dogs might number a billion. Their future, at least in terms of numbers, is bright. As long as there are people, there will be dogs. No one knows what they will look like, and whether we will have to brush their teeth day and night, and spend a fortune on their haircuts. But they will be here. The same cannot be said of wolves. And as wild creatures go extinct, we all lose.

Nomads, Herders and Livestock Migrations

Herders have traditionally moved their animals between the high summer pastures of the mountains and their villages camps on steppes where they spend the winter. They pick up and move two or three times a year, typically in May and October, usually remaining within a 25-square mile area, and relocate from November to April in a winter camp with some stone shelters for the animals.

Herders will stay in an area as long as the there is enough grass. Where grazing land is more scarce nomads roam across large swaths of empty plains, mountains and grassland, having to travel longer distances and pack up and move maybe ten or so times a year or as often as twice a week. Moving the animals around also allows the grass to grow back.

There are no fences, except around cities, Herders have traditionally takes their animals to where the pastures were best. In the dusty steppes and sandy deserts they find places where wild grasses grow tall and find places in the mountains were the pastures are sweet.

In some cultures men ride on horses and women and ride on horseback or on the pack animals. Camels have traditionally been used to move possessions, with everything loaded on their backs: tent parts, carpets, pots and pans, shelves, stoves. These days trucks often fulfill this duty.

It takes a nomad around two weeks to slowly move his animals, which graze along the way, 100 kilometers. The nomads don’t need maps and GPS devices; they use the sun, stars, the shape of hills and mountains and landmarks to find their way.

Seasonal Migrations

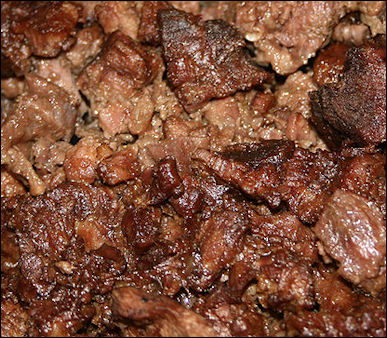

Moroccan preserved dried meat The pastures are divided according to season — summer, spring/fall, and winter based on the amount of grass and when the grass is sufficient to eat, which is often determined by geography, climate conditions and season. The summer pastures are usually located in the north in the steppe areas or in the mountains. These areas have abundant, lush grass but heavy snows made it impossible for the animals to graze. In the winter the animals are taken to the south to the desert and semidesert zones, where autumn rains are imperative for producing grass for animals to eat.

Groups that lived near mountains migrate between the high pastures in the summer and the river valleys in the winter. The distance between pastures and the river valleys is often less than 50 miles. When the conditions are favorable large groups sometimes set up their tents together in the open pastures and gather for circumcision ceremonies, weddings, funerals, festivals and family reunions that often feature dancers and animal races.

The main migrations are between summer and winter pastures. Between them nomads stay briefly at fall and spring pastures. Nomads that move overland between the northern steppes and the southern semideserts are known as “meridanal” nomads while those that migrate up and own the mountains were called “vertical” nomads. The nature of the migration, the type of grass available and the market price for animals and family and clan needs determine which animals are raised.

Meat and Artificial Meat

The world consumes 240 billion kilograms of meat every year. The British food writer Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall has said the fat and brains of one animal taste pretty much like the fat and brains of another; the lungs are known as “lights” in British butchering lingo; brains are a pain to extract; testicles and ears are tasty; and supermarket meat exudes water when it is cooked because it is “water-aged” rather than “dry-aged” to make it heavy so it can be sold at a higher price.

David Sedaris wrote in The Guardian: “Like most westerners I tend towards herbivores, and things that like grain: cows, chickens, sheep, etc. Pigs eat meat — a pig would happily eat a human — but most of the pork we're privy to was raised on corn or horrible chemicals rather than other pigs and dead people. There are distinctions among the grazing animal eaters as well. People who like lamb and beef, at least in north America, tend to draw the line at horse, which in my opinion is delicious. The best I've had was served at a restaurant in Antwerp, a former stable called, cleverly enough, The Stable. Hugh was right there with me, and though he ate the same thing I did, he practically wept when someone in China mentioned eating sea horses. "Oh, those poor things," he said. "How could you?" [Source: David Sedaris, The Guardian July 15, 2011]

meat cooked for Muslim holiday It is possible to create meat in a petri dish in a laboratory. Both NASA and the Dutch government are experimenting with the idea using a process in which myoblasts — muscle precursor cells that behave sort of like stem cells — are extracted from a living animal and encouraged to multiply in a slurry of glucose, amino acids, minerals and growth agents. The cells are placed in a bioreactor where they are stretched, using electrical impulses, until they form muscles fibers. The result is “meat sheets” that can be pealed off and ground up into hamburgers or sausages. [Source: Ben MacIntyre, Times of London, January 2007]

The process is very experimental and in the early stages of its development. At this juncture it is also very expensive. Growing a kilogram of “meat” using the method described above costs roughly $10,000. But who knows: scientists believe the process holds ths potential for producing healthier, cleaner meat that uses up less resources and doesn’t require killing any animals. In 2006 scientists at Touro College in the United States made artificial meat from the abdomen of anesthetized goldfish and coated in bread crumbs and fried it in olive oil. The results they said “smelled good” but they didn’t eat it.

Ecological Problems with Meat

Meat production is a very wasteful process. About 75 percent of what is fed to an animal is lost through metabolism or is in the form of inedible parts such as bone. Every kilogram of beef requires 16,000 liters of water to produce it. On top of that there is greenhouse gas production, deforestation, contamination and pollution from pesticides and fertilizer and disease. Many of the world’s worst diseases — tuberculosis, avian flu, swine flu and mad cow disease — are linked with livestock.

The British food writer Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall wrote, “Most of the meat we eat comes from industrially farmed animals who lead miserable lives and are fed on inappropriate diets.” Hormones, antibiotics and other chemicals added to livestock have been blamed for causing early breathing difficulties in children and diseases that are difficult to treat with conventional means. The run off from manure and chemicals linked to the production of meat have been blamed for contaminating fields and rivers. Animals are fed cheap grains and butchered with high pressure hoses. The slaughtering process leaves behind millions of kilograms of carcasses that are incinerated or buried.”

Over half the synthetic fertilizer used in the United States goes to producing corn and soy beans for the livestock industry. Fertilizer run off is a leading cause of marine dead zones. Livestock production consumes 70 percent of the water in the American West — water so heavily subsidized that if supports were removed ground beef would cost more than $70 a kilogram.

Livestock accounts for 21 percent of greenhouse gas emissions — more than all forms of transportation combined. In the United States, domestic animals consume 70 percent of all the antibiotics produced. Undigested antibiotics from manure leach into the soil and into freshwater systems and impair the sex organs of fish.

Industrial Slaughtering Livestock

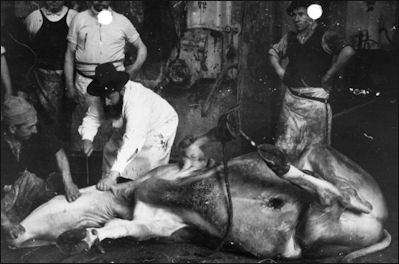

Kosher butcher Fearnley-Whittingstall has asked “why is it considered entertaining when predators make a kill in a nature film “whereas the final moments of human predation of our farmed livestock are considered too disturbing and shameful to be made available even for information.”

Describing the slaughter of livestock animals, Bill Buford wrote in The New Yorker, the animals are “backed up against a corral....Then: a captive bolt gun [is] pressed against the top of an animal’s head. Then: the animal [is] on its side on a concrete floor, collapsed, blood starting to pool. It is raised by its hind legs and hung upside down to drain the blood. It is skinned, a thick layer of white fat peeled off the body in a single rug piece. This is followed by a tug-of-war removal of unwieldy, instantly expanding intestines like a white plastic trash bag filled to bursting, and the sawing of the carcass in half, the moment when conventional butchering begins.”

Cloned Animals and GM Animals

In January 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration said that meat and milk from cloned animals was safe. European regulators had come to a similar conclusion. At $10,000 to $20,000 per animal, clones are too expensive to be used as meat sources and are used to produce meat-producing offspring. Among the animals clone in the United States have been prize-winning cows and rodeo bulls.

Domesticated mammals that have been cloned include: 1) sheep (Dolly in 1997) ; 2) a bull (1999, leading to a debate about the safety of milk and meat from clones); 3) pigs (2000, opening the way for the cloning of animals to produce organs, possibly for human transplants); 4) goats (2000, the first one died of abnormal lung development); 5) cat (2002, quickly followed by the formation of a company to make clones of cherished pets); 6) mule (2003, the first hybrid clone, mules are offspring of a horse and a donkey); 7) dog (2005, achieved with an Afghan by South Korean researchers) ; 8) water buffalo (achieved in China in 2005); 9) horse (2005, achieved with a surrogate mother that was also a genetic donor).

Alok Jha wrote in the Guardian, “Though there are no transgenic animals currently approved for human consumption, they might not be far away. Last year, the US Food and Drug Administration proposed allowing the sale of the AquAdvantage salmon — a modified North Atlantic salmon created by AquaBounty Technologies in Boston, Massachusetts. The company says the salmon grows at twice the speed of similar fish.” [Source: Alok Jha, The Guardian, January 13, 2011]

Genetically-engineered Coho salmon with a modified gene that allows them to grow at a faster pace, especially in the winter, can reach a weight up to 30 times greater than non-genetically-engineered salmon. Scientists are not sure what would happen if genetically-engineered salmon escaped into the wild.

slaughtering a goat for Muslim holiday AquaBounty, a Massachusetts-based company, wants to market a genetically engineered version of Atlantic salmon. The company has argued their case in hearings before the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is weighing the request. If approved, the fish would become the first genetically-modified animals to be designated safe for human consumptions.. Ron Stotish, chief executive of AquaBounty, has said that his company's fish product is safe and environmentally sustainable. FDA officials is leaning towards approval, saying that the salmon, which grows twice as fast as its conventional salmon is as safe to eat as the traditional variety. But they have not yet decided whether to approve the request. [Source: Mary Clare Jalonick, AP, September 20, 2010] See Sea, Fish Farming

Livestock Diseases

Foot and mouth disease affects cows, sheep, goats and other cloven-footed animals. Not usually fatal, it causes blisters on the mouth and feet. Foot and mouth disease doesn’t affect humans but it is highly contagious among animals. It usually starts with a loss of appetite and fever. When outbreaks occur authorities cull animals and quarantine affected areas. Other countries often ban meat from the infected country.

Mad Cow Disease is the name the media gave to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE for short), a degenerative brain disease for cattle that many scientists believe became widespread in Britain in the 1990s after a large number of cattle consumed animal feed made with the remains of brains sheep that died from scrapie (a disease similar to BSE). The disease was called the Mad Cow Disease because infected cattle, drooled, staggered and acted strange before they dropped dead.

The strange disease that affected the humans was similar to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), a rare, painful, incurable, always-fatal disease that kills by eating away sponge-like holes in the victim's brain. When the Mad Cow scare began 10 Britons had been diagnosed with the new disease, eight of them having already died. Several of the victims worked on a farm, in a slaughter house or as a food processor.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024