KINGFISHERS

Kingfishers are small-to-medium-sized, colorful birds with a long, straights beaks that hunt for fish and other small creature by dive bombing into shallow water. They often have bright iridescent feathers. Cobalt blue with a touch red are common colors. Some species have a slightly hooked beak. Straight beaks are suited mainly for striking and grasping prey while slightly hooked ones are designed for holding and crushing.

Kingfishers belong to the order Coraciiformes and the family Alcedinidae. Within Coraciiformes, kingfishers are grouped into the suborder Alcidines, with todies (Todidae) and motmots (Motmotidae). Alcedinidae comprises approximately 19 genera and 118 species, and is frequently subdivided into three subfamilies; Alcedininae, which comprises most of the “fishing” kingfishers, Halcyoninae, which comprises the “forest kingfishers” that reside primarily in Australasia, and Cerylinae, which includes all of the New World kingfishers. [Source: Kari Kirschbaum, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kingfishers have short necks and large heads to go along with their long, thick bills. They live primarily in wooded habitats of tropical regions, often near water. Despite their name, not all kingfishers are fishing specialists. While some species do consume primarily fish, most species have unspecialized diets that include a high proportion of insects. Most kingfishers are monogamous, territorial breeders, though a few species breed cooperatively. |

Fossils of kingfishers from as early as 40 million years ago have been found in Wyoming in the U.S. Kingfishers are thought to be relatively long-lived, but the lifespan unknown for most species. Adult annual survival is thought to range between 25 and 55 percent. A common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) is among the oldest known kingfishers at 15 years and five months. A captive laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae) also lived over 15 years. Sources of kingfisher mortality include predation, collection, and collision with man-made structures such as windows, towers and building during nocturnal (active at night), migrations. |=|

RELATED ARTICLES:

KOOKABURRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, LAUGHING, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOWERBIRDS: BOWERS, TYPES, DECORATIONS, COURTSHIP DISPLAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOWERBIRD SPECIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LYREBIRDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

RIFLEBIRDS (PTILORIS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS OF AUSTRALIA: COMMON, UNUSUAL AND ENDANGERED SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, COLORS factsanddetails.com ;

BIRD FLIGHT: FEATHERS, WINGS, AERODYNAMICS factsanddetails.com ;

BIRD BEHAVIOR, SONGS, SOUNDS, FLOCKING AND MIGRATING factsanddetails.com

Kingfisher Habitat and Where They Are Found

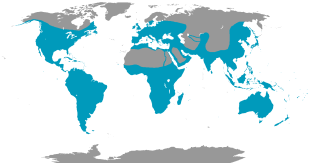

Kingfishers are found in all regions of the world, except in polar regions and on some oceanic islands. The majority of kingfisher species are tropical. Most kingfishers are found the Australasian (Australia, New Zealand, and the surrounding Pacific islands), Africa and Asia, with the highest numbers in the Australasian region. Only six species, all in the subfamily Cerylinae, occur in the Americas.

Most kingfishers live in forested or open woodland habitat, often near water. Slightly less than half of species live in closed-canopy forests (primary and secondary), around 18 percent of species live in wooded savannas, and 33 percent are found in aquatic habitats including seashores, mangrove swamps, lakes, rivers and streams. One species lives in desert scrub. |=|

The main habitat requirements for kingfishers are food and nest site availability. Forest-dwelling species are generally found in the lower levels of the canopy where they forage from the forest floor. Kingfishers that require aquatic habitat can be found most often near small water bodies such as mountain streams, rivers and lakes. Most also require perches near the shore to hunt from, but a few species are able to hunt by hovering, and can forage up to three kilometers from shore. Kingfishers excavate nests in earthen banks (usually), tree cavities (either natural, excavated by other animals, or excavated by the kingfishers if the wood is sufficiently rotten) or termite nests. Many kingfishers show a remarkable ability to adapt to different habitats, and may shift between very different breeding and non-breeding habitats. Kingfishers live at elevations of sea level to more than 2800 meters. [Source: Kari Kirschbaum, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kingfisher Characteristics

Kingfishers are 10 to 46 centimeters (3.9 to 18.1 inches) long and weigh nine grams to half a kilograms (0.3 ounces to 1.1 pounds). They are thickset birds with large heads, short necks, short legs, and long, thick bills. For the most part sexual dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. female larger Ornamentation is different. Kari Kirschbaum wrote in Animal Diversity Web: They typically have rounded wings and a short tail, though eight species of paradise kingfishers have long tail streamers. Kingfishers have small, weak, 3- or 4-toed feet that are fused, meaning that the front toes are all fused to some degree. The bill and feet of adult kingfishers are black or bright red, orange or yellow, and the eyes are usually dark brown. Kingfishers are generally colorful and boldly marked, often with blues and greens above and a mixture of red, orange and white below. Many species also have a pale collar and several species have a distinctive crest. [Source: Kari Kirschbaum, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The bills of kingfishers are all long and thick, but vary in shape in accordance with the foraging habits of each species. Fly-catching species have dorsoventrally flattened bills, whereas fishing species have laterally flattened bills. Ground-feeding species, including shovel-billed kingfishers (Clytoceyx rex) usually have shorter, quite broad bills. |=|

The sexes of most kingfisher species are similar in size and plumage, though some species show distinct differences. For example, the males of some paradise kingfishers have much longer tail streamers than females. Reversed sexual size dimorphism (females markedly larger than males) is found in the two largest kookaburra species, laughing kookaburras (Dacelo novaeguineae) and blue-winged kookaburras (Dacelo leachii). Juveniles typically look similar to adults, with somewhat duller plumage and often with mottling where adults have solid coloration. |=|

Like motmots and todies, kingfishers often have brilliant plumage, are largely insectivores (eat insects), and nest in cavities that are often excavated in earthen banks. Kingfishers are distinguished by their long, thick, straight beak and plumage that is more often blue than green. |=|

Kingfisher Food and Eating Behavior

Kingfishers are carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and primarily insectivores (eat insects and non-insect arthropods) but are also recognized as piscivores (eat fish) and can be molluscivores (eat molluscs). Kingfishers mainly eat insects and other arthropods, small fish, frogs and crawfish they catch by diving into the surface of a lake, stream or river. They like to perch on branches overlooking prime hunting spots and often sit on one spot patiently, without moving for long periods of time, waiting for an unsuspecting fish to come within range. Kingfishers especially like ponds or lakes with trees that they can use as perches overhanging the water. They ideally like to be near shaded areas, where fish often congregate. Some kingfishers hunt over land rather water.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Despite the name of this group, not all kingfishers are fish specialists. Many kingfishers are unspecialized carnivores that are often largely insectivores, and may take prey from the ground, the air, water or foliage. Kingfishers are highly adaptable, and will generally take whatever prey is available. Their diets can include a variety of insects (frequently grasshoppers), reptiles, (skinks, snakes), amphibians, mollusks, non-insect arthropods (centipedes, millipedes, scorpions, spiders, crabs), mice, and even small birds. Those species that are fish specialists usually also include some insects in their diet. One species of kingfisher has been seen eating carrion, and a few species occasionally eat berries or the fruit of oil palms. Kingfishers can take prey that are large relative to their body size. For example, laughing kookaburras can take snakes up to one meter long, though the tail may protrude from their bill for a time while the head end is digested. [Source: Kari Kirschbaum, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Other feeding specialists among the kingfishers include shovel-billed kingfishers (Clytoceyx rex) which use their beak to plough through earth and leaf-litter, looking for earthworms, grubs, snails, centipedes and lizards. Ruddy kingfishers (Halcyon coromanda) in the Philippines remove land snails from their shells by smashing them against stones on the forest floor. A few species follow other animals (including otters, platypus, cormorants, egrets, cattle or army ants) to catch prey that they disturb. Some species also attend grassfires to catch prey that are scattered by the flames. Kleptoparasitism has been reported in several species; the victims included blackbirds, song thrushes, water shrews, hawks and tree snakes. |=|

The majority of kingfisher species hunt from a perch, surveying quietly for prey, and swooping down to surprise it. A few species search for prey while flying, and a few others forage on the ground. Most species catch prey by surprising it, and rarely chase prey for any length of time. Once a kingfisher catches a prey item, it carries it to a perch (often the same one from which it was hunting) and uses its beak to beat the prey item against the perch until it is soft enough to swallow whole. This preparation removes the legs and wings of insects and breaks the bones, protective spines, and shells of fish, crustaceans and other prey. |=|

Diving Kingfishers

The “fishing” kingfishers can dive up to two meters below the surface of the water to catch fish. Kari Kirschbaum wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Some have a nictitating membrane that covers and protects their eyes as they enter the water, which means that they must anticipate the movements of their prey before they enter the water, and rely on their sense of touch to determine when to snap their beak shut. [Source:Kari Kirschbaum, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kingfishers rarely dive deeper than 30 centimeters and catch most of their prey near lake shores or river banks. They do not pursue their prey underwater like cormorant or grebes. If they don’t have any success in their initial plunge they return to their perch and try again later. If they catch a fish they do not tear it to pieces rather they maneuver it around into the right position inside their bill and swallow it head first. Sometimes they slam their prey against a branch to kill it or stun it and make it easier to swallow.

Kingfishers can hoover above the water, They can't do it as long as hummingbirds and most species need some wind to do it. Even their hoovering ability is quite extraordinary and required a radical alteration of the basic bird skeleton to achieve. Describing a kingfisher capturing a small fish, David Attenborough, wrote in The Life of Birds, "the turquoise blue kingfisher sits on a perch above a stream, short of tail but armed with a long dagger of a beak. At the sight of a small fish in the water below, it will flash into action. If its perch is a low one, only a few feet above the surface of the water, it will fly upwards to gain height to give itself room to gain speed on its dive."

"Then down it comes increasing its momentum with a few flickering wing-beats. With its wings extended but folded back tightly against its body, it plunges into the river. Its target may be minnow or a stickleback, Even if it is as much as three feet below the surface, the kingfisher will be able to reach it. Beating its wings below water to help it rise, the little bird shoots through the surface and flies off to a perch. There is kills its victim by thrashing its head against some hard object, and with one gulp, swallows it."

Kingfisher Behavior

Kingfishers fly and are diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), employ aestivation (prolonged torpor or dormancy such as hibernation), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Most are relatively sedentary (remain in the same area) but some can be migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds). [Source: Kari Kirschbaum, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

According to Animal Diversity Web (ADW): Most kingfishers live as solitary breeding pairs that defend a territory year-round. Several species defend their territory to the extent that they attack other species, including other birds, goannas, weasels, dogs and cats. A few species, such as pied kingfishers (Ceyx lecontei) and laughing kookaburras (Dacelo novaeguineae) are cooperative breeders. In these species, cooperative groups, which include a breeding pairs and one to several helpers defend a territory together. At night, most kingfishers roost alone on a perch within their territory. During incubation, females may roost in the incubation chamber. |=|

Many species of kingfishers have been observed bathing by diving repeatedly into water. Kingfishers generally preen frequently, and anting has been observed in at least one species of kookaburra. Most species are sedentary, but about a few species are migratory, or partially migratory. Unlike many bird species, some kingfishers migrate during the day. All but one species of kingfishers are diurnal. The nocturnal (active at night), species is hook-billed kingfishers (Melidora macrorrhina), which feed largely at night. Many species are inactive during the hottest part of midday. |=|

There are relatively few records of adult kingfisher predation. Kingfishers are quick fliers, and probably able to escape most predators. Most known predators of adult kingfisher are raptors. Nest predators include foxes, minks, dingoes, skunks, raccoons, chimpanzees, snakes , monitor lizards, driver ants, and mongooses. When threatened, kingfishers seem to employ one of two strategies; they either try to evade the predator by dodging behind trees or diving into the water, or they attack the predator directly, mobbing it until it leaves the area. A few species have alternative strategies; yellow-billed kookaburras raise their head feathers when threatened, revealing two black spots that resemble large eyes. When alarmed, young red-backed kookaburras assume a posture with their eyes closed and their beak pointed upward that make them look like the limb of a tree from above. Kingfishers aggressively defend the nest area against nest predators, often attacking intruders including humans. |=|

Kingfisher Senses and Communication

Kingfishers sense using vision, ultraviolet light, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses. They communicate with vision and sound. They also employ duets (joint displays, usually between mates, and usually with highly-coordinated sounds) and choruses (joint displays, usually with sounds, by individuals of the same or different species) to communicate.[Source: Kari Kirschbaum, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Kingfishers have very good eyesight, and rely heavily on sight for hunting. Their eyes have two fovea, which allow them to very accurately judge the distance to a prey item by turning their head slightly. Their eyes are also especially rich in oils that enhance color vision. At least one species of kingfisher is able to see near UV light. When some kingfishers dive for fish, their eyes are covered by a nictitating membrane. This means that these species must rely on their sense of touch to know when to snap their bill closed in order to catch the fish. |=|

Kingfishers are highly vocal species that used calls to advertise their territory and to communicate between family members. Some pairs of kingfishers call in duets (joint displays, usually between mates, and usually with highly-coordinated sounds), and cooperative groups of kookaburras call in a chorus at dawn and dusk. While the vocalizations of most species are not well studied, those species that have been studied often have several different vocalizations. For example, belted kingfishers (Megaceryle alcyon) use at least six calls in various combinations to convey messages. Several species also produce non-vocal sounds, such as bill rattling. |=|

Kingfisher Mating and Reproduction

Kingfishers are usually monogamous (have one mate at a time) but some are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). They engage in seasonal breeding and year-round breeding and are cooperative breeders (helpers provide assistance in raising young that are not their own). Courtship displays often involve loud calls and flights over the treetops. A male courting a female, often brings her one or two fish, carrying them crossways in his bill.

Kari Kirschbaum wrote in Animal Diversity Web: All kingfishers are territorial. Most are also monogamous, and many pair for life. Courtship involves aerial chases, individual and joint displays, and courtship feeding. Breeding pairs emphatically defend a territory using calls and displays, which can include spiraling flight displays or displaying boldly marked plumage by perching high within the territory and spinning slowly around a vertical axis. Kingfishers actively defend their territory, chasing intruders and when necessary, grappling in the air, sometimes toppling to the ground or into the water where the fight continues. Particularly aggressive neighbors may even enter the nest cavities of one another to puncture eggs. Territory size varies between species and with food abundance and nest site availability. Where nest sites are particularly scarce, a few species of kingfishers will breed in loose colonies and defend only an area immediately surrounding the nest hole. [Source:Kari Kirschbaum, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Some species of kingfishers are cooperative breeders. In these species, a male and female pair has one to several “helpers” that help defend the territory and feed the chicks. Helpers can be primary (related) or secondary (unrelated). They are often young from previous broods that may help at the nest for several years, and can dramatically increase nestling survival in some cases. Polygamy is known to occur in at least one species of kingfisher; male common kingfishers (Alcedo meninting) in Russia frequently breed with up to three females. |=|

Kingfisher Offspring, Nesting and Parenting

Kingfishers make their nests in burrows in river banks or hollows of trees or rotted logs. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is provided by both females and males. Both sexes participate in digging a burrow. Most kingfishers rear one brood per year. However, under favorable conditions, some species may rear up to four broods per year. In some cases, the male may even begin digging a new nest tunnel before the young of the previous clutch have fledged. Chicks are fed regurgitated pellets.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Most kingfishers that have been studied begin breeding at one year old, and can raise one to four broods per year. The female lays two to 10 (usually three to 6) white, unmarked eggs that weigh two to 12 grams each. Eggs are laid approximately one day apart, and incubation begins either when the first egg is laid, or after the majority of eggs have been laid. The naked and blind chicks hatch synchronously in species where incubation does not begin until most or all eggs have been laid, and asynchronously in species where incubation begins with the first or second egg. Siblicide is common in the latter. Nestlings fledge three to eight weeks after hatching, and are dependent on the parents for supplemental food for several days to weeks after fledging. In most species, the adults eventually force the fledglings to leave their territory. The timing of breeding varies considerably within this family. Generally, kingfishers in temperate regions breed during the spring and summer. Those in tropical regions can breed year-round or seasonally during the time of highest prey availability. |=|

Kingfishers nest most often in earthen banks such as those along rivers or lakes, but they also use termite nests and tree cavities. Tree cavities made by other species, such as woodpeckers, are readily used. If these are not available, kingfishers will excavate a cavity in wood (if it is sufficiently rotten), or another substrate. The male and female excavate the cavity together, taking turns pecking and scraping material with their bills and feet. Several species begin excavation by flying bill-first into the surface, an occasionally fatal strategy. The tunnel to a kingfisher nest cavity may be as long as three meters. The cavity is slightly larger in diameter than the tunnel, and is not lined with any material. Nest cavities can take up to a week to excavate, and pairs often use the same nest hole for many years. |=|

Both male and female kingfishers incubate the eggs, which take two to four weeks to hatch. During the nestling stage, which lasts three to eight weeks, both parents feed the young regurgitant, and later whole prey items. During the last part of the nestling stage, parents may feed each chick as frequently as once every 15 minutes. When the nestlings are large enough to fly, the parents may withhold food for a few days to encourage the chicks to leave the nest. After the chicks have fledged, the parents provide supplemental food while the chicks learn to hunt for themselves. Some kingfishers also teach their young to hunt. For example, belted kingfishers (Megaceryle alcyon) drop dead prey into the water for their young to practice diving. After up to three weeks of supplemental feeding, adult kingfishers usually force their young to leave their territory. Adult kingfishers do not engage in any nest sanitation, such as removing feces from the nest cavity. Because most kingfisher nests have only one outlet, nests can become rather smelly and are often infested with maggots as feces from the chicks and food scraps accumulate. |=|

Kingfishers, Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, most kingfishers are classified as a species of “Least Concern”. According to Animal Diversity Web: The biggest threat facing most kingfisher populations is the destruction or alteration of their habitat by logging, pollution of water bodies and development. Significant numbers of kingfishers are also killed by shooting, collision with cars and buildings, and accidental poisoning from pesticides and poisons intended for other species. While it appears that many species of kingfishers are relatively adaptable to changes in habitat, the biology of most species is not well known, making conservation planning or prediction of impacts to habitat difficult. |=|

According to the IUCN Red List, there are four critically endangered kingfisher species, one endangered species, 11 vulnerable species, and 12 near-threatened species. Most of endangered pr threatened species are forest species with limited distribution, particularly insular species. They are threatened by habitat loss caused by forest clearance or degradation and in some cases by introduced species. The Marquesan kingfisher of French Polynesia is listed as critically endangered due to a combination of habitat loss and degradation caused by introduced cattle, and possibly due to predation by introduced species. [Source: Google AI, Wikipedia]

Kingfishers sometimes take privately owned fish from fish farms or garden ponds. Otherwise they are generally shy birds and stay clear of humans and their activities. But despite this, they are featured in human culture, generally due to their large head, long bill bright plumage and interesting behavior. Among the Dusun people of Borneo, the Oriental dwarf kingfisher is considered a bad omen, and warriors who see one on the way to battle should return home. Another Bornean tribe considers the banded kingfisher as a good omen. The sacred kingfisher, along with other Pacific kingfishers have been venerated by the Polynesians, who have believed they had control over the seas and waves. As a symbol of dexterity and wisdom, kingfishers also inspire literary works from the Southeast Asian region, such as Wild Wise Weird: The Kingfisher Story Collection. We can’t forget Kingfisher beer from India.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025