WASPS

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant. The most commonly known wasps, such as yellowjackets and hornets, are in the family Vespidae. They are eusocial, living together in a nest with an egg-laying queen and non-reproducing workers. [Source: Wikipedia]

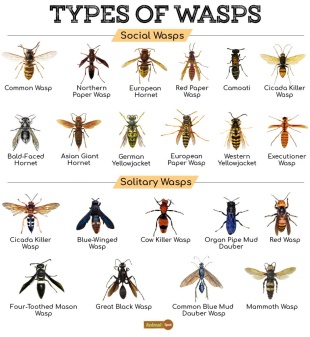

According to National Geographic: Wasps make up an enormously diverse array of insects, with some 30,000 identified species. We are most familiar with those that are wrapped in bright warning colors—ones that buzz angrily about in groups and threaten us with painful stings. But most wasps are actually solitary, non-stinging varieties. And all do far more good for humans by controlling pest insect populations than harm.

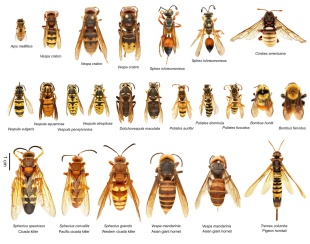

Wasps are distinguishable from bees by their pointed lower abdomens and the narrow "waist," called a petiole, that separates the abdomen from the thorax. They come in every color imaginable, from the familiar yellow to brown, metallic blue, and bright red. Generally, the brighter colored species are in the Vespidae, or stinging wasp, family. All wasps build nests. Whereas bees secrete a waxy substance to construct their nests, wasps create their familiar papery abodes from wood fibers scraped with their hard mandibles and chewed into a pulp.

Some species of wasps have extremely weird and cruel parasitic life cycles. A number lay their eggs in the eggs or larvae of other insect species and the larvae that hatch feed in various ways on the eggs and larvae of their hosts. The “Copidosama floridanum”, native throughout the United States and studied by Mike Strand of the University of Georgia, arguably has the weirdest life cycle of all, beginning 1) when an adult female wasp lays one or two eggs inside a cabbage looper moth egg. 2) As the moth egg develops into five-to seven-centimeter-long caterpillar, the grape-like wasp eggs release about 3,000 genetically-identical maggot-like wasp larvae, most of which drink the caterpillar’s blood. 3) Up to a quarter of the larvae take on snakelike “soldier” forms that attack wasp larvae and eggs which have the same mother they do. 4) The bloodsucking larvae that are not killed by soldiers devour their hosts and pupae. 5) The wasps that develop from the surviving larvae and eggs eventually fly away, leaving the soldier larvae trapped inside the mummified caterpillar. [Source: Carl Zimmer, New York Times, August 14, 2007]

RELATED ARTICLES:

BEES: HONEY, STINGS, AFRICANIZED KILLERS factsanddetails.com ;

INSECTS: CHARACTERISTICS, DIVERSITY, USEFULNESS, THREATENED STATUS factsanddetails.com ;

KINDS OF INSECTS: MANTIDS, CICADAS AND ONES THAT KILL HUMANS factsanddetails.com ;

FLYING INSECTS: FLIES, DRAGONFLIES, FIREFLIES factsanddetails.com ;

MOSQUITOES: BLOOD, DISEASE AND AVOIDING AND KILLING THEM factsanddetails.com ;

ANTS: PHERMONES, QUEENS, COMMUNICATION, HUNTING AND ENSLAVEMENT factsanddetails.com ;

ANTS THAT MAKE MILK, EXPLODE AND FORM ARMIES factsanddetails.com

Hornets

Hornets are omnivorous insects. They feed on nectar but also hunt grasshoppers, crickets and other insects. Typically they sting their prey cut them apart with their powerful jaws, and the carry the cut up pieces back to their nest and feed them to growing larvae. The nests of temperate hornet species, which can reach the size of a beach ball, are constructed from spring through autumn and abandoned in the winter and a new nest is built. At that time of the year males emerge and fly off to different places and wait there for female queens to show up. After the queens come out they mate with males and then look for a nice warm, dry spot to spend the winter. In the spring new queens begin building a new nest from scratch.

Hornets have a smooth stinger that slides in and out of their targets. They uses it for hunting and are able to use it repeatedly. In contrast bees have a barbed stinger that pulls off when inserted and yanked. They sting only in defense and use their stinger only once.

Temperate hornets are often aggressive in late autumn when the new queens develop, workers become more protective, food become scarcer and large species of hornets attack the nests of smaller species. If attacked by a hornet get as far away as possible from the nest as soon a possible, the initial attackers placed a pheromone onto the skin of its target — whether it be a person or animal — that identifies it as an enemy and the target for other hornet attacks.

Hornet Life Cycle

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Hornets “construct large nests. A single queen starts the nest in early spring, and her offspring, the workers, continue to expand it well into autumn. By this time of year, the nests are reaching maximum size, and in some species may house several thousand workers. Workers, although all females, do not mate or lay eggs. Their job description includes building the nest, hunting for food for the larvae and defending the colony against intruders. Come winter all of them will die off. Genetically programmed to be totally unselfish, if threatened they will defend the nest with reckless abandon. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, October 18, 2012]

As autumn wanes, a change comes over the nest. Until now all the larvae were destined to metamorphose into additional workers. Now, however, two special types of larvae are being raised. One type will metamorphose into males, and the other into a cadre of new queens. After metamorphosing, the males will leave their natal nest. They will fly around looking for another nest of the same species, then just sort of hang out idly on the outskirts. When the new queens emerge, the males will be waiting there to mate with them. Their one and only function in life is mating, and they die soon afterward. [Ibid]

After mating, the new queens will preserve the males' sperm in special pockets, then search for a warm cozy place to spend the winter. When they reawaken next spring, each queen will start building a nest of her own from scratch. All hornet nests, including some that are as big as a beach ball, have been constructed over the course of a single season. The founder queen and all the workers will die with the coming cold, and the old nest will be abandoned. [Ibid]

An autumn nest is the product of six months of hard work, the sole purpose of which is to raise a set of males and new queens to foster the next generation. As might be expected, the workers become especially sensitive and aggressive while the new queens and males are growing inside. Their attack threshold in mid to late autumn is thus considerably lower than in the warmer months. [Ibid]

Hornets and Bees

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Hornets are close relatives of bees, but are fundamentally different in terms of feeding ecology. Bees raise their larvae on nectar and pollen collected from flowers. Hornets, in contrast, do sip pollen and nectar for short-term energy boosts, but feed their larvae a steady meat diet. They hunt and kill caterpillars, grasshoppers and other insects, then use their powerful jaws to cut out bite-size pieces to carry back to the nest. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, October 18, 2012]

Bees sting only to protect their nests. In many species, the poison stinger is tipped with a barb that catches in the flesh of the enemy. When the bee pulls away, her abdomen rips apart, leaving the barbed stinger inside the victim. These bees can sting only once. Hornets, however, use their stingers not only in defense of the nest, but in their daily hunting chores as well. Their stingers are thus not barbed, and can be used over and over again.

Local farmers are a bit ambivalent about the local hornets. On the one hand, they recognize that these predatory insects eliminate large number of caterpillars and other crop pests. On the other hand, farmers who keep honey bees to pollinate their strawberries and other fruits and vegetables fear the hornets. The larger species often attack honey bee hives to get at the larvae inside. A squadron of a few dozen hornets can wipe out an entire hive in no time. [

Imported European honey bees have no defenses against a hornet raid. The workers rush out bravely, but are quickly cut to pieces by the hornets' powerful jaws. The ground around a raided hive will be littered with decapitated bees. Native Japanese honey bees, however, have evolved alongside the hornets, and have developed a technique for protecting themselves. Rather than trying to sting the intruders, they simply blanket them in huge numbers. This raises the hornets' body temperature and kills them.

Bees

Bees have barbed stingers that pull out when inserted in a target and yanked out. They sting only in defense and use their stingers only one. In contrast hornets have a smooth stinger that slides in and out. They use it for hunting as well as defense and are able to use it repeatedly.

A French mathematician concluded in 1934 that it defied science that bumble bees were able to fly. Bumble bees and other beers do have small wing to body sizes but are able to compensate for this by working harder than other insects and flapping their wings in unusual ways. Their unorthodox flapping methods lets them hoover, evade predators and get lift even when loaded up with nectar.

Most flying insects move their wings in long, sweeping strokes (140 to 165 degrees) at roughly 200 beats a second. But honeybees flap in short arcs (about 90 degrees) so they have to compensate with more speed (up to 240 times a second). To beat gravity bees beat their wings plus flip them. When they fly bees: 1) first flap forward creating a vortex above the bee and generating lift. 2) The wings then rotate and slow down in preparation for the backward stroke. 3) In the next step the wings finish rotating and start sweeping backwards, utilizing the previous stroke’s wake. And 4) Finally, the wings fling backwards, creating a new vortex in the process. The cycle then repeats.

Bees are widely used to pollinate agricultural plants. Beekeeping is encouraged in many places as a way for poor farmers to make supplementary income.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Mostly National Geographic articles. Also David Attenborough books, Live Science, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024