SINGAPORE AFTER WORLD WAR II

When the Japanese surrendered in 1945, Singapore was handed over to the British Military Administration, which remained in power until the dissolve of the Straits Settlement comprising Penang, Melaka and Singapore. In March 1946, Singapore became a Crown Colony. "The Japanese occupation nightmare was over and people thought the good times were about to return," Lee Kuan Yew wrote. "By early 1946, however, people realized that there was to be no return to the old peaceful, stable, free-and-easy Singapore. The city was packed with troops in uniform. They filled the newly-opened cafés, bars and cabarets...It was a world in turmoil where hucksters flourished. Much of the day-to-day business was still done on the black—now the free—market." [Source: Library of Congress]

Japan’s surrender in 1945 did not bring an immediate return to stability or prosperity in Singapore. The British Military Administration ended in March 1946, after which Singapore was reconstituted as a Crown Colony. Penang and Malacca, by contrast, were incorporated into the Malayan Union in 1946 and later into the Federation of Malaya in 1948. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

In the postwar period, Singapore’s commercial community began pressing for a more active role in politics. Initially, constitutional authority remained concentrated in the hands of the governor, who was advised by a council composed of officials and nominated non-official members. In July 1947, this arrangement evolved into separate Executive and Legislative Councils. Although the governor continued to exercise substantial control, provisions were made for the election of six members to the Legislative Council by popular vote. These reforms culminated in Singapore’s first election, held on 20 March 1948.

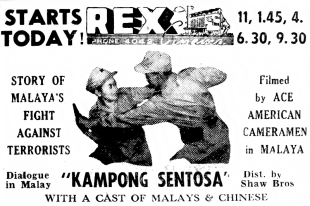

Meanwhile, efforts by the Communist Party of Malaya to seize control of Malaya and Singapore by force led to the declaration of a state of emergency in June 1948. The Emergency persisted for twelve years, shaping the political and security environment of the region. Against this backdrop, the British government in late 1953 appointed a constitutional commission chaired by Sir George Rendel (1889–1979) to reassess Singapore’s political status and recommend reforms. The commission’s proposals were accepted and formed the basis of a new constitution that granted Singapore a significantly greater degree of self-government.

In the decades after World War II, Singapore was known as a crime-ridden city filled with opium addicts, revolutionaries and gangsters. The stereotype image of Singapore in this era was steamy bars, with a slow moving ceiling fans, where unrepentant colonials, war correspondents, sailors, fugitives and expatriate writers downed shots of whiskey and traded stories about Communist insurgencies and bar girls. Singapore also suffered from communist terrorism,

RELATED ARTICLES:

SINGAPORE HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

JAPAN'S MALAYA CAMPAIGN AND DEFEAT OF THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE DURING WORLD WAR II: POOR BRITISH DEFENSE, HARSH JAPANESE OCCUPATION factsanddetails.com

POLITICAL ACTIVITY IN PRE-INDEPENDENCE SINGAPORE: PAP, LEE KUAN YEW, COMMUNISTS, LABOUR FRONT factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE INDEPENDENCE: SELF RULE, UNION THEN SPLIT WITH MALAYSIA, CHALLENGES factsanddetails.com

LEE KUAN YEW — SINGAPORE'S FOUNDER-MENTOR — AND HIS LIFE, VIEWS AND DEATH factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE UNDER LEE KUAN YEW factsanddetails.com

GOH CHOK TONG: SINGAPORE'S PRIME MINISTER FOR 14 YEARS AFTER LEE KUAN YEW factsanddetails.com

LEE HSIEN LOONG: SINGAPORE'S PRIME MINISTER FROM 2004 TO 2024 factsanddetails.com

British Re-Enter Singapore After World War II

After World War II, Singapore was excluded from both the Malayan Union and, later, the Federation of Malaya established in 1948. Instead, it remained under direct British rule until 1959, when it was granted internal self-government. Singapore was reoccupied by the British in September 1945. In 1946, Singapore was constituted a crown colony with Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, which are in the middle of nowhere in the Indian Ocean southwest of Indonesia. Singapore was no longer part of the Straits Settlements as Penang and Malacca became part of Malaysia. Later, Singapore separated from Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands and became a self-governing state in June 1959. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

The abrupt end of the war took the British by surprise. Although the Colonial Office had decided on the formation of a Malayan Union, which would include all the Malay states, Penang, and Malacca, no detailed plans had been worked out for the administration of Singapore, which was to be kept separate and serve as the headquarters of the British governor general for Southeast Asia. Many former colonial officials and businessmen opposed the separation of Singapore from peninsular Malaya, arguing that the two were economically interdependent and to exclude Singapore would "cut the heart out of Malaya." The Colonial Office maintained that the separation did not preclude union at some future date, but that union should not be forced on "communities with such widely different interests." In September 1945, Singapore became the headquarters for the British Military Administration (BMA) under Mountbatten. Although Singaporeans were relieved and happy at the arrival of the Commonwealth troops, their first-hand witnessing of the defeat of the British by an Asian power had changed forever the perspective from which they viewed their colonial overlords. [Source: Library of Congress]

In 1946 Singapore became a separate crown colony with a civil administration. When the Federation of Malaya was established in 1948 as a move toward self-rule, Singapore continued as a separate crown colony. The same year, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) launched an insurrection in Malaya and Singapore, and the British declared a State of Emergency that was to continue until 1960. The worldwide demand for tin and rubber had brought economic recovery to Singapore by this time, and the Korean War (1950–53) brought even further economic prosperity to the colony. However, strikes and student demonstrations organized by the MCP throughout the 1950s continued to arouse fears of a communist takeover in Malaya.

Economic and Social Recovery in Singapore After World War II

The British returned to find their colonies in sad shape. Food and medical supplies were dangerously low, partly because shipping was in total disarray. Allied bombing had taken its toll on Singapore's harbor facilities, and numerous wrecks blocked the harbor. Electricity, gas, water, and telephone services were in serious disrepair. Severe overcrowding had resulted in thousands of squatters living in shanties, and the death rate was twice the prewar level. Gambling and prostitution, both legalized under the Japanese, flourished, and for many opium or alcohol served as an escape from a bleak existence. The military administration was far from a panacea for all Singapore's ills. The BMA had its share of corrupt officials who helped the collaborators and profiteers of the Japanese occupation to continue to prosper.

As a result of the inefficiency and mismanagement of the rice distribution, the BMA was cynically known as the "Black Market Administration." However, by April 1946, when military rule was ended, the BMA had managed to restore gas, water, and electric services to above their prewar capacity. The port was returned to civilian control, and seven private industrial, transportation, and mining companies were given priority in importing badly needed supplies and materials. Japanese prisoners were used to repair docks and airfields. The schools were reopened, and by March 62,000 children were enrolled. By late 1946, Raffles College and the King Edward Medical College both had reopened. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Food shortages were the most persistent problem; the weekly per capita rice ration fell to an all-time low in May 1947, and other foods were in short supply and expensive. Malnutrition and disease spawned outbreaks of crime and violence. Communist-led strikes caused long work stoppages in public transport, public services, at the docks, and at many private firms. The strikers were largely successful in gaining the higher wages needed by the workers to meet rising food prices. *

By late 1947, the economy had began to recover as a result of a growing worldwide demand for tin and rubber. The following year, Singapore's rubber production reached an all-time high, and abundant harvests in neighboring rice-producing countries ended the most serious food shortages. By 1949 trade, productivity, and social services had been restored to their prewar levels. In that year a five-year social welfare plan was adopted, under which benefits were paid to the aged, unfit, blind, crippled, and to widows with dependent children. Also in 1949, a ten-year plan was launched to expand hospital facilities and other health services. By 1951 demand for tin and rubber for the war in Korea had brought economic boom to Singapore. *

By the early postwar years, Singapore's population had become less transitory and better balanced by age and sex. The percentage of Chinese who were Straits-born rose from 36 percent in 1931 to 60 percent by 1947, and, of those born in China, more than half reported in 1947 that they had never revisited and did not send remittances there. Singapore's Indian population increased rapidly in the postwar years as a result of increased migration from India, which was facing the upheavals of independence and partition, and from Malaya, where the violence and hardships of the Emergency caused many to leave. Although large numbers of Indian men continued to come to Singapore to work and then return to India, both Indians and Chinese increasingly saw Singapore as their permanent home. *

In 1947 the colonial government inaugurated a ten-year program to provide all children with six years of primary education in the language of the parents' choice, including English, Malay, Chinese, and Tamil. Seeing an English education as offering their children the best opportunity for advancement, parents increasingly opted to send their children to English-language schools, which received increased government funding while support for the vernacular schools declined. In 1949 the University of Malaya was formed through a merger of Raffles College and the King Edward Medical College.

Communist Threat in Post-World War II Singapore

Communist-inspired subversion and violence was a serious problem in Malaya and Singapore in the post-World War II period. In June 1948, the British colonial government declared a state of Emergency in Malaya and Singapore and passed tough security laws to cope with the threat. After Lee Kuan Yew led the PAP to victory in the 1959 election, the influence of the communists quickly declined and citizens known or alleged to have contacts with the MCP or other groups that advocated the overthrow of the government were closely monitored by the police. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987*]

The MCP was legal in Singapore during the first two-and-one- half years of post-war British colonial rule. The communist-controlled Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army, formed during the Japanese occupation, had several hundred Chinese members, including the commander, Chin Peng. In 1945 and 1946, many poorly educated Chinese Singaporeans sympathized with the communists because they seemed to offer a program of labor reforms that would benefit the common man. Additionally, most of the better educated Chinese resented British policies that limited participation in politics to Straits-born British subjects who were literate in English. A large segment of the Chinese community also supported the Chinese Communist Party as it moved closer to gaining control in China.

Chin Peng was elected secretary general of the MCP in March 1947. At that time, the communists had an estimated 300 members in Singapore who were committed to the party's goal of destabilizing the British regime by promoting civil unrest in the trade unions. In 1947 communist fronts were influential in organizing over 300 strikes involving more than 70,000 workers. Economic concessions by the colonial government and business community reduced but did not destroy communist influence, and communist leaders gradually became more militant. They recruited former guerrillas of the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army and members of various secret society gangs to form the underground Workers' Protection Corps. When the communists were unsuccessful in penetrating targeted trade unions, small groups belonging to the Workers' Protection Corps used various methods of intimidation in an effort to have moderate leaders replaced by communists or communist sympathizers.*

The party's chance to take over Singapore from the British through legal means ended in 1948 when the communist leaders decided to adopt a strategy of insurrection and terrorism in Malaya and Singapore, which led to the period known as the Emergency. The MCP was declared illegal and was subjected to countermeasures by the government; its membership in Singapore dropped precipitously, and all of the members of the Singapore Town Committee, which was the CPM's central committee for Singapore, were arrested in December 1950. The communist effort was crippled until the mid-1950s, when a new strategy of collaboration with legal political organizations was adopted by the government.

The communist movement survived in Singapore largely in the Chinese-language middle schools, whose students were particularly susceptible to propaganda because their employment and political opportunities were much more limited than those of English-speaking Chinese. After 1949 the success of the communists in China also attracted students to the party. The organizing force behind student activity was the Singapore Chinese Middle School Students Union. Because of the unpopularity of the 1954 National Service Ordinance, which required males between the ages of eighteen and twenty to register for conscription or face jail or a fine, the communists had little difficulty in organizing violent student demonstrations. No popular uprising in support of the communists ever materialized, however.*

In 1956 when it had become clear that the British were going to leave Singapore, the communists moved to obtain control of an independent government by legal means while continuing to foster disorders. In October 1956, after more rioting by students and laborers, Singapore's police raided labor unions and schools and rounded up large numbers of communists and communist supporters. The concurrent effort by the communists to find a legal route to power focused on the party's alliance with the PAP.

Organizers of the PAP had deliberately collaborated with the communists in order to broaden the PAP's organizational base among the Chinese majority, and the communists saw in the leftist orientation of the PAP an ideologically acceptable basis for an alliance. When the communists attempted to seize control of the PAP Central Executive Committee in 1957, however, they were defeated by supporters of Lee Kuan Yew. Lee went on to lead the PAP to victory in the 1959 election. As prime minister, Lee gradually eliminated communists from influential positions within the party and government and later used provisions of the Internal Security Act to prevent alleged communists from participating in politics.*

In February 1963, the Singapore and Malaysian police forces organized a joint operation that resulted in the arrest of 111 suspected communists in the two countries. This large-scale police action targeted suspected MCP members in Singapore and successfully destroyed the party's underground political organization in Singapore. In 1989 there were no reports of the CPM's having reestablished a base of operations in the country.*

Riots in Singapore 1950 and the Government Response

In response to communal riots in December 1950, the British reorganized the Singapore Police Force and established links between the police and the British army that effectively prevented subsequent civil disturbances from getting out of hand. The 1950 riots occurred when Malay policemen, who comprised 90 percent of the police force, failed to control a demonstration outside Singapore's Supreme Court. The demonstration occurred following a decision by the court to return to her natural parents a Dutch Eurasian girl who had been raised in a Malay foster home during the Japanese occupation. Incensed by the court's decision, large groups of Malays randomly attacked Europeans and Eurasians killing 18 and wounding 173. The British army had to be called in to restore order. [Source: Library of Congress]

The British reorganization of the police force included the hiring of large numbers of Europeans, Chinese, and Indians to improve the ethnic balance; the establishment of riot control teams; and the modernization of police command and communication channels. The riot control teams belonged to a new organization known as the Police Reserve Unit. Members of the unit had to be politically reliable and had to pass a rigorous training course. The first riot control teams were deployed in December 1952. In May 1955, these units were effective in containing communist-inspired rioters during a transportation workers' strike, although four people were killed and thirty-one injured over a three-day period.*

In July 1956 the Singapore government under Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock's government prepared an internal security plan that simplified arrangements for cooperation between the police and the British army during serious civil disturbances. The new plan provided for a joint command post to be set up as quickly as possible after the police recognized the possibility of a riot. The Police Reserve Unit was to assume responsibility for riot control operations within clearly defined sectors while army units were deployed to control the movement of civilians in the immediate area.

The plan was tested and proved effective during communistinspired riots in October 1956, when five army battalions supported the police and five helicopters were used for aerial surveillance of the demonstrators. Police and army cooperation succeeded in breaking up large groups of rioters into smaller groups and preventing the spread of the violence to neighboring communities. Police and army restraint kept deaths and injuries to a minimum and improved the confidence of the public in the government's capability in handling incidents of domestic violence. The British role was a stabilizing factor that facilitated the demise of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP, also known as the Communist Party of Malaya, CPM) in Singapore and a smooth transition of power to the People's Action Party (PAP).*

Chinese Raise Their Ambitions and Education Levels in Post-World War II Singapore

Although the Chinese-educated took little interest in the affairs of the Legislative Council and the colonial government, they were stirred with pride by the success of the CCP in China. Fearful that support by Singapore's Chinese for the CCP would translate to support for the MCP, the colonial government attempted to curtail contacts between the Singapore Chinese and their homeland. When Tan Kah Kee returned from a trip to China in 1950, the colonial government refused to readmit him, and he lived out his days in his native Fujian Province. [Source: Library of Congress *]

For graduates of Singapore's Chinese high schools, there were no opportunities for higher education in the colony. Many went to universities in China, despite the fact that immigration laws prohibited them from returning to Singapore. To alleviate this problem, wealthy rubber merchant and industrialist Tan Lark Sye proposed formation of a Chinese-language university for the Chinese-educated students of Singapore, Malaya, and all Southeast Asia. Singaporean Chinese, rich and poor, donated funds to found Nanyang University, which was opened in Singapore in 1956. *

By the early 1950s, large numbers of young men whose education had been postponed by the Japanese occupation were studying at Chinese-language high schools. These older students were particularly critical of the colonial government's restrictive policies toward Chinese and of its lack of support for Chinese- language schools. The teachers in these schools were poorly paid, the educational standards were low, and graduates of the schools found they could not get jobs in the civil service or gain entrance to Singapore's English-language universities. While critical of the colonial government, the students were becoming increasingly proud of the success of the communist revolution in China, reading with interest the publications and propaganda put out by the new regime. *

Decline of British Military Influence in Singapore

British military influence in Singapore was reestablished at the end of World War II and declined at a slower pace than London's political influence. Singapore was made the headquarters for British forces stationed in the East Asia. The local population's resentment of British rule was tempered by the magnitude of the social and economic problems remaining after the Japanese occupation. Britain's military expenditures provided jobs and promoted support for its political objectives in the region.

From 1948 to 1960, Malaya and Singapore were under emergency rule as a result of the threat posed by the MCP. Throughout this period, the majority of Singapore's political and business leaders were strong supporters of the British military presence. As Singapore moved from being a crown colony, to becoming a state in the Federation of Malaysia, and finally to independence in 1965, the British armed forces continued to be viewed as the protector of Singapore's democratic system of government and an integral part of the island's economy. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987*]

By 1962 the British were questioning the strategic necessity and political wisdom of stationing forces in Singapore and Malaya. At that time London was spending about US$450 million annually to maintain four infantry battalions, several squadrons of fighter aircraft, and the largest British naval base outside the British Isles, even though Southeast Asia accounted for less than 5 percent of Britain's foreign commerce.*

In January 1968, the British government informed Prime Minister Lee that all British forces would be withdrawn from the country within three years. By then Singapore already had begun to organize its army and to plan for the establishment of an air force and navy. The British left behind a large military infrastructure and trained personnel of the newly formed Air Defence and Maritime commands. London formally ended all responsibility for Singapore's defense in 1972 when it turned over control of the Bukit Gombak radar station to Singapore.*

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Singapore Tourism Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated February 2026