PUTAO

PUTAO (northernmost Myanmar) is a the largest town in northeastern Myanmar. Myanmar's and Southeast Asia’s highest mountain, 5,861-meter-high (19,320 foot-high) Hkakabo Razi, is about 50 miles from Putao. In the markets you can see body parts of a wide variety of wild animals. Many people who live here have never seen a white perosn. The road between Myitkyina and Putao is lovely and very rough. It takes two days to make the journey by bus, if there are no major breakdowns and the roads are passable. Putao can also be reached by plane.

Putao is located near snow-peaked mountains and the weather is cold around the year. The town itself is a small district capital with around 10,000 people. There are many different ethnic minority tribes in the area. Flowing streams and rivulets, straw-roofed houses and fences of pebbles and creek stones provide a pleasant, pastoral contrast to the scenes and sights of modern cities. Suspension bridges made of wood, ropes and vines are the typical river crossing in this region. People of the Rawan, Lisu, Khamti-Shan, Jingphaw and Kachin are represented in the region.

This Putao is famous for its nature and unique flora. There are many various kinds of orchids. Even super rare black orchids can be found in this area. And for fauna one of the rarest animal species takin as well as red panda, black bears, black deer, monkeys, boars, mountain goats are seen in this region. Various kinds of butterflies can be seen in this area, especially in January. The Butterflies include rare and endangered species such as the Kaiser, Apollo, Bhutan, and Glory. Among the flora are different kinds of rhododendrons, maple trees and various kinds of bamboos. The months of January and April are the best times to see butterflies, flowers and orchids in the icy forest.

Kawn Moo Lon Golden Sambur King Pagoda (10 miles east of Putao) is situated in Kham Ti Lung area 12 miles from Machambaw, on east bank of Malikha River. It was one of 84,000 pagodas built by Thiri Dhamma Thawka the great king, enshrining three relics under the tutelage of Thatitha Arahantha, at the place of demise of the king of sambur that was the embryo-Buddha left on Hinthagon (Ngun Pik) Hill many existences ago. In the east entrance are an image of Kakusana Buddha, Matali nat and Manuthiha, in the north an image of Gonaguna Buddha, king of nats, and king of wuns, in the west an image of Kassapha Buddha, Wathondaray guardian of the earth, and figure of a lion, in the south an image of Gautama Buddha, a figure of an ogre and a king of tigers. In the south-east are a satellite pagoda and an image of Arimetreya.

Visiting Putao

On his journey to Putao organize a trip to the village of Rat Baw, about thirty miles from the Chinese border, Jamie James wrote in Natural History magazine: “Our flight north was slightly terrifying, aboard an ancient commuter plane that looked ready for the scrap heap. When we skittered to a landing in Putao, I found myself in the middle of a broad plain encircled by distant blue mountains, the southeastern edge of the Himalayas. Concealed by the closer peaks, to my north lay Hkakabo Razi, at 19,294 feet. At the only decent restaurant in Putao, I met with Yosep Kokae, an experienced guide.

My rush to get to Rat Baw and back before my permit expired was soon revealed to be pointless. In Putao I learned that my flight to Yangon had been cancelled indefinitely. So I was stranded there with a trio of British birdwatchers, staying in an unheated guesthouse next door to a karaoke club that catered to very drunk loggers. The birders told me that they had sighted the Burmese bushlark, hooded treepie, white-browed nuthatch, white-throated babbler, and several species of bulbul. They held out little hope for the pink-headed duck, Rhodonessa caryophyllacea, a legendary waterfowl with a head as pink as bubble gum. It is almost certainly extinct; the last reported sighting was in 1966.

A week later, an airlift was organized for us, serendipitously scheduled for the morning after Putao's annual festival. This country fair consisted mainly of dart-throwing gambling games, booths selling beer and fried snacks, and karaoke. The chief attraction was a performance by an inept rock band, Claptonian noodling laid over a thumping pop rhythm of bass and drums. Yosep Kokae was there with his wife; Khun Kyaw and his compadres were flirting with the girls, boasting about their adventure. Perhaps 500 people milled about watching the show. Outside Burma it might have been accounted a pretty poor festival, but after my trip to Rat Baw it seemed like a jubilant saturnalia. [Source: Jamie James, Natural History magazine, June 2008]

Traveling by Motorcycle from Putao

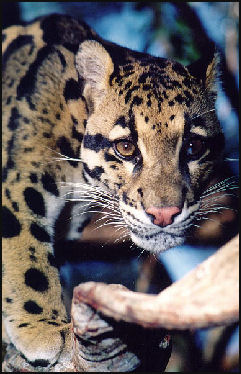

Clouded leopard

Jamie James wrote in Natural History magazine, “The area I wanted to visit had been a site of active resistance by guerilla groups until the mid-1990s, and the presence of foreigners there is restricted. I had only managed to obtain a ten-day pass to Putao and environs. A guide was also assigned to accompany me—a tall, serious, bespectacled man of twenty-seven named Lynn Htut Oo, who continually reminded me of the importance of giving him a big tip. With the aid of my government guide, I immediately set about organizing an expedition to Rat Baw. The village lies in a rugged area that is home to hill tribes that came from around Tibet hundreds of years ago. Known collectively to outsiders as the Kachin, they call themselves by the names of their tribal groups, among them the Jingpaw, Rawang, and Lisu. [Source: Jamie James, Natural History magazine, June 2008]

“The forests in the valleys around Rat Baw “partake of the character of tropical rain forest.” So wrote the botanist Frank Kingdon-Ward, who traveled to Burma ten times from 1914 to 1956, bringing back showy species that became staples of English gardens. At the only decent restaurant in Putao...Then the restaurant's owner, a tall, dignified Kachin woman, told me that her son and his friends might be willing to take me to Rat Baw on their motorcycles. Her son, Khun Kyaw, a strapping, self-confident twenty-two-year-old, recruited two friends, making a party of six with me, my government guide, and Yosep Kokae. It wasn't ideal, roaring through the wilderness on cheap Chinese motorbikes, but I had no alternative. Just as we were about to depart, the local constabulary decided that we must have another official minder on the expedition, so we were assigned a timid twenty-year-old policeman, whom Khun Kyaw and the others treated with open contempt.

“It was a cool, misty morning when we set off, seven men on six bikes, laden with bottled water and freshly killed chickens. On the outskirts of town we passed several Protestant churches, simple bamboo structures with wooden crosses surmounting their flimsy entrance gates. Burma is overwhelmingly Buddhist, but most of the people around here follow Christianity. The earliest known missionary to the Kachin was Eugenio Kincaid, a Baptist preacher from Wethersfield, Connecticut, who paddled a small boat loaded with bibles and religious tracts some 400 miles up the Irrawaddy from Mandalay in 1837.

“A few miles out of town, we crossed a fine iron suspension bridge spanning a northern tributary of the Irrawaddy. Elephants were stacking freshly felled trees on the riverbank, awaiting a barge from Myitkyina, the capital of Kachin State, to collect them. It was the last evidence of logging activity I would see on the trip. A good paved road led to the village of Machanbaw, the last outpost of relative civilization; after that, the trail became narrow and overgrown, climbing steadily to an elevation of 2,000 feet. Although it lies north of the Tropic of Cancer, the forest here has a distinctly subtropical character, with towering dipterocarps, Chinese coffin trees, flowering magnolias, fragrant screw pines, and many fruit trees, including rambutan, mangosteen, and banana, all wrapped in thick ropes of lianas and other climbers. The British botanist Frank Kingdon-Ward described the terrain in his account of a collecting expedition in 1953: “Here the forest is richer and denser—not only does frost never enter into these deep sheltered valleys, but throughout the winter they are steeped in mist till nearly midday, and so partake of the character of tropical rain forest.”

“Kingdon-Ward was the hardest-working and most productive of the foreign scientists...in the region. In ten epic journeys to Burma from 1914 to 1956, he collected dozens of plant species new to science, and brought back hundreds of varieties of begonias, poppies, rhododendrons, and other showy flowering plants, which became staples of English gardens. His vivid, often witty journals of those expeditions were popular reading for British Sunday gardeners.

Exploring the Jungles and Forests of the Putao Area

Jamie James wrote in Natural History magazine, “We made our first camp at a village called Htanga. It was wretchedly poor, malaria was rampant, and the people were obviously not getting enough to eat. Yet the inhabitants were wonderfully hospitable, giving us the best house in town, a rickety bamboo structure on stilts with a thatched roof. For dinner, Yosep Kokae made “bachelor's chicken,” a mild, savory curry served with tiny fried potatoes, the size of garbanzo beans, which had a delicious, nutty flavor. Later, a few children sneaked up to see us. They were fascinated by my battery-powered lantern; one little boy blew on the light bulb as if it were a flame or ember, trying to make it glow more brightly. [Source: Jamie James, Natural History magazine, June 2008]

“We awoke to a misty morning. Yosep Kokae was already busy cooking fried rice with chilies. Breakfast began with pomelo, the fruit of Citrus maxima. One of the volleyball-size fruits—the largest of the citrus fruits—fed us all. Its mild grapefruit tang was sharpened with a dash of salt. My bowl had a fried egg on top, the only one, laid overnight by the hen that lived on the back porch. One of the bikes wouldn't start, so we abandoned it there, along with our useless police escort.

“After we had been an hour on the road, our surroundings took on a wilder aspect, so I told the guys to break for a few hours. I went ahead on foot and was soon surrounded by dense forest. I saw a hornbill swoop overhead, a reliable harbinger of wilderness; farther along I heard a pair of gibbons serenading each other. The most thriving forms of wildlife I observed, however, were the leeches. The morning mist gave them a congenial environment in low-hanging foliage. Kingdon-Ward wrote after an expedition to Putao District in 1937, “It was rather horrible to see the hordes of famished leeches advancing immediately one entered the jungle. It is almost indecent how they smell their victim and sway their way towards him, the foliage shivering to their regular movements.”

“By midday the weather had cleared, and the landscape displayed an exquisite, rugged beauty—high rock cliffs with waterfalls plunging a hundred feet or more, soaring trees, ferns with fronds five to ten feet long, stands of many varieties of bamboo, and treelike rhododendrons. I passed some boys catching tiny fish in a creek with conical, thorn-lined traps. Where a tree had fallen across the trail, I sat to wait for my escort. In a shady recess by a small creek I found a black orchid—a rare flower, but not as beautiful as its name.

“At dusk, just as a light rain began to fall, we reached Rat Baw, tucked into a valley between two high ridges that vanished into swirling clouds. Home to forty-eight families, the village has a rustic, Tolkienesque charm: bamboo fences crisscross the gentle hillside, ruling off neat vegetable patches; the low roofs of the houses, thatched with fan-palm leaves, blend imperceptibly with the surrounding secondary forest. A dirt path curves back toward the river, leading to the schoolhouse, a solid frame building with a tin roof. It was here Joe Slowinski died.” Slowinski was herpetologist who died from the bite of rare snake. See Animals.

“We pitched our tents in the main classroom. After dinner the schoolmaster, Joseph Tawng Wa, invited me to his house behind the school, just as he had Slowinski in 2001. His house was almost in ruins, with gaping holes in the floor and roof. Wild spearmint grew all around, covering the mild funk of cow dung. A grave, placid man with two gold incisors, Wa wore a Norwegian ski sweater against the damp cold. He had lost three of his five children to malaria. He opened a bottle of homemade rum and we talked about our lives. He told me he loved America, and showed me a laminated portrait of Bill Clinton he carried in his wallet.

Recalling the death of Slowinski, Wa said, “We were so sad, sir. The lady teachers all wept. The men teachers were also very sad.” He was upset that Slowinski had refused to take mashaw-tsi, the local herbal cure for snakebite. He claimed that no one in Rat Baw ever died of snakebites, thanks to the plant's miraculous curative power. Kingdon-Ward was the first to identify the herbal remedy as a species of the genus Euonymus. At that time a Kachin elder controlled the market for the precious herb. “This cheerful old rogue,” wrote Kingdon-Ward, “claimed a monopoly not only in purveying mashaw-tsi—at a price—to the public, but even in the occurrence of the plant, which he maintained grew only in the jungle near his village.” (Later in Putao, I bought a sprig in the market for a few cents.) In the morning, Wa told me, “You are very fortunate to find me here.” After six years as schoolmaster in Rat Baw, he had been offered a new job, and was leaving for good just four days later.

Hukaung

HKAKABO RAZI LANDSCAPE

Mt. Hkakaborazi (around Putao, near where Myanmar, China and India meet) is the highest peak in Myanmar and Southeast Asia at 5,881 meters (19,295 feet). Hkakabo Razi Landscape was nominated to be a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2014. According to a report submitted to UNESCO:The Northern Mountain Forest Complex (NMFC) consists of Hkakabo Razi National Park (NP) and Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary (WS), along with a proposed Southern Extension of Hkakabo Razi NP. Hponkan Razi WS, Hkakabo Razi NP, and the proposed Southern Extension form a contiguous property of more than 11,280 square kilometers. Elevation ranges from 50 meters at the southern end of Hponkan Razi WS to over 5,800 meters. The property borders India and China and includes Mt. Hkakaborazi, which at 5,881 meters is the highest peak in Southeast Asia. Mt. Hponkan Razi rises to 5,165 meters. [Source: Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar]

Hkakabo Razi NP and Hponkan Razi WS’s scenic beauty includes forest-covered mountains, undammed rivers flowing through deep canyons, sharp ridges, and stunning snow-capped peaks, including the highest mountain in Southeast Asia: The dramatic landscape and natural state of the environment here combine to produce an exceptionally scenic landscape. The property is inhabited by a about 2,000 people, 500 of whom live in the town of Naung Mung inside the proposed Southern Extension. The rest of the population, including the Rawang and Tibeto-Burman groups, live in smaller, scattered settlements along the river valleys.

Hkakabo Razi NP was established in 1998 and covers 3,810 square kilometers, making it the second largest protected area and largest national park in Myanmar. It is also an ASEAN Heritage Park. Hponkan Razi WS was gazetted in 2003 and covers about 2,700 square kilometers (Instituto Oikos and BANCA 2011). Hkakabo Razi NP’s proposed Southern Extension covers the area south of the current park boundary to the northern edge of the Putao plain and from Hponkan Razi WS in the west to the N’mai Hka River in the East. This area ranges in elevation from 500 to 2,900 meters and covers 4,778 square kilometers, which would more than double Hkakabo Razi NP’s area. The area contained within the proposed extension is of particularly high bird endemism and diversity.

Its very low population and inaccessibility have protected the NMFC from development. Fewer than 8,000 people live in the property: 6,000 in Putao, which is located outside of the property, and 500 in Naung Mung, inside the proposed protected area. Small settlements in the proposed extension are home to about 1,500 more people. The NMFC enjoys a remarkable degree of ecological integrity. Renner et al. (2007) report less than 0.01% deforestation annually between 1991 and 1999 and the deforestation that has occurred is concentrated in the sparsely populated river valleys, including Mali Hka and Nam Tamai, and in the flood plains of Putao and Naung Mung. Swidden cultivation has created a patchwork of secondary forest fallows in various stages of regeneration extending up hillsides from inhabited river valleys.

Hkababo National Park (east of the town of Tahawdam) is located where Myanmar, China and India all come together. To the east, the property is contiguous with the Gaoligonshan Nature Reserve (NR), which is one component of the Three Parallel Rivers (TPR) of Yunnan Protected Areas WHS in China. To the west, the property is contiguous with Namdapha NP in India. Namdapha NP was submitted to India’s TL in March 2006 for criteria vii, ix, and x (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2013a). The contiguous area protected across Myanmar, India, and China in these three properties totals 17,390 square kilometers.

Ecosystem of Hkakabo Razi Landscape

According to the report submitted to UNESCO: The Northern Mountain Forest Complex includes a suite of forest types transitioning across 5,830 meters of vertical elevation. Subtropical evergreen forest at lower elevations transitions to temperate evergreen forest, mixed deciduous forest, pine-rhododendron forest, alpine meadows, and at the highest elevations into snow-capped alpine peaks. Globally threatened wildlife includes the Black Musk Deer, Red Panda, and White-bellied Heron. [Source: Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar]

The NMFC covers an area of outstanding size and ecological diversity. At the transition between three biogeographical zones and two ecoregions, it is an area of high endemism and diversity that showcases evolutionary and ecological processes. Even when not considered in combination with the contiguous protected areas in China and India, the NMFC provides sufficient scale and diversity for evolutionary processes to occur, including seasonal altitudinal migrations, potentially in response to climate change. When transboundary properties are taken into account, it represents a still greater example of conservation at a landscape scale.

The NMFC covers 11,280 square kilometers of Eastern Himalaya habitat across an altitudinal range from below 1,300 meters to over 5,800 meters. It contains a diversity of forest types across this elevation gradient, from lowland evergreen forests up to alpine meadows. This diversity of habitats supports a variety of endangered wildlife, including several that are endemic to the property. Its position at the convergence of three biogeographical regions, Eurasia, the Indian subcontinent, and Indochina, has resulted in high levels of endemism and species richness. It is also located at the convergence between Palearctic and Indo-Malayan ecozones, therefore containing both temperate and tropical components. The Southern Extension strengthens the OUV of the property because it contains an area of high bird species richness and areas in which vertebrate species new to science have recently been discovered (Renner and Rappole 2011). The very large size, diversity, and intactness of ecosystems across the NMFC, and its location next to large protected areas in China and India creates an exceptional contribution to conservation across the Eastern Himalayan range.

Threats to the property include potential logging and mining concessions. Infrastructure development plans are reported around Putao and could result in in-migration and increased human impacts. Other pressures include the commercial hunting of wildlife and gathering of non-timber forest products within the existing park boundaries. The Black Musk Deer has been heavily hunted for use in traditional Chinese medicine and its population has declined across the region (Rao et al. 2010). Imawbum is currently or potentially impacted by dams, logging, and mines. These may not necessarily pose a direct threat to the Myanmar Snub-nosed Monkey but do raise questions about the site’s long-term integrity and compatibility with the rest of the complex. Hkakabo Razi NP and Hponkan Razi WS are both managed out of the same office in Putao, which should assist in their joint management as a single WHS.

Wildlife in the Hkakabo Razi Landscape

According to the report submitted to UNESCO: Its location on multiple biogeographical transition zones has given the NMFC high species endemism and diversity. Diversity of birds and butterflies is particularly high. Surveys have recorded more than 80 species of amphibians and reptiles, 442 species of birds, 360 species of butterflies, 297 species of trees, and 106 species of orchids (Oikos and BANCA 2011; Renner et al. 2007). Both Hkakabo Razi NP and Hponkan Razi WS are Important Bird Areas and lie within the Eastern Himalaya Endemic Bird Area (EBA 130), which includes 19 restricted-range bird species, 10 of which are globally threatened (BirdLife International 2013). [Source: Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar]

Since 1999, nine vertebrate species new to science have been described in the NMFC, including the Leaf Deer (Muntiacus putaoensis), catfish (Clupisoma sp.), new bird species and subspecies, including the Naung Mung Scimitar-Babbler (Jabouilleia naungmungensis), and several reptiles (Renner et al. 2007). The Gongshan Muntjac (Muntiacus gongshanensis)andLeaf Deer (Muntiacus putaoensis) are both DD. Considering the limited scientific exploration of the area it is likely that more will be discovered. The proposed Southern Extension contains rainforest areas with high bird diversity, with many species’ ranges overlapping in the 900-1,500 meters band. This extension also has high endemism and is the site of multiple of the recent species discoveries in the NMFC (Renner and Rappole2011). A potential addition to the NMFC is the proposed Imawbum protected area, which is located 150 kilometers to the southeast along the Chinese border and is connected to the NMFC through Gaoligongshan NR. Imawbum strengthens the NMFC’s natural values by including habitat of the recently discovered CR Myanmar Snub-nosed Monkey (Rhinopithecus strykeri). It lies within the Yunnan Endemic Bird Area.

Globally threatened or DD species in the NFMC and proposed extension include (Myanmar Biodiversity 2012):Mammals: Endangered: Black Musk Deer (Moschus fuscus), Shortridge’s Langur (Trachypithecus shortridgei), Chinese Pangolin (Manis pentadactyla), Dhole (Cuon alpinus); Vulnerable: Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens), Red Goral (Naemorhedus baileyi), Takin (Budorcas taxicolor), Hoolock Gibbon (Hoolock spp.), Himalayan Black Bear (Ursus thibetanus), Sun Bear (Helarctos malayanus), Clouded Leopard (Neofelis nebulosa), Marbled Cat (Pardofelis marmorata), Bengal Slow Loris (Nycticebus bengalensis),Sambar (Rusa unicolor), Stump-tailed Macaque (Macaca arctoides). Birds: Critically Endangered: White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis); Vulnerable: Blyths Tragopan (Tragopan blythii), Sclater’s Monal (Lophophorus sclateri), Rufous-necked Hornbill (Aceros nipalensis), Beautiful Nuthatch (Sitta formosa), Snowy-throated Babbler (Stachyris oglei) Near-threatened: Rusty-bellied Shortwing (Brachypteryx hyperythra). Reptiles: Endangered: Keeled Box Turtle (Cuora mouhotii); Vulnerable: Impressed Tortoise (Manouria impressa). Plants: Endemic: Paphiopedilum wardii, Euonymus burimanicus, Euonymus kachinensis, Rhododendron spp.

HUKAWNG VALLEY WILDLIFE SANCTUARY

HUKAWNG VALLEY WILDLIFE SANCTUARY (near India in northwest Myanmar) is one of the remotest places in Myanmar and home to some the last large concentrations of wild life in Southeast Asia. Located between the Samgpang and Kumon mountains, it is has hardly any people living in and is virtually void of roads and villages. Much of the travel in the area is done on foot or by boat on the Tanai and Turung Rivers. Tanai is the largest town near the valley. The three ethnic groups that dominate the region are the Kachin who live in the lowlands and the Naga and Lisu who live in the highlands. For a long time the areas was controlled by the Kachin Independence Army (KIA).

The Hukawang Valley is sometimes called the Valley of Death after the number of Allied soldiers that died here during the building of the Ledo Road in World War II. After the war much of the road was quickly reclaimed by jungle .Even though the KIA signed a peace treaty with the Myanmar government in 1994 the group refused to give up its arms and retained bases in the jungles in the valley. An effort is being made to convince local tribal people and miners to raise livestock so they rely less on wild game for meat. [Source: Alan Rabinowitz, National Geographic, April 2004]

Hukaung Valley Wildlife Sanctuary was nominated to be a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2014.According to a report submitted to UNESCO: The Hukaung Valley Wildlife Sanctuary (HVWS) and its extension are located in northwest Myanmar and falls in both Sagaing Division and Kachin State and cover a total area of 17,890 square kilometers. HVWS and extension form a doughnut whose unprotected center covers the floodplain of the Chindwin River, the largest tributary of the Ayeyarwady River. The floodplain is inhabited by some 50,000 people. Established in 2001, HVWS covers 6,371 square kilometers. In 2004, the extension was established, adding 11,519 square kilometers. Hereafter, the two sites are referred to as the HVWS. To the east and northeast, it is contiguous with Bumhpabum WS and Hponkan Razi WS. To the north, it abuts Namdapha National Park (NP), which was put on India’s TL in March 2006 (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2013a). Forest areas within HVWS are primarily evergreen. At higher elevations, mixed deciduous forest, evergreen hill forest, and pine forest are present. Globally threatened wildlife includes the Asian Elephant, Tiger, and White-bellied Heron. [Source: Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar]

About 50,000 people live in the unprotected central valley, the majority of whom are Kachin. Naga and Shan ethnic groups also live in the valley. HVWS is an excellent example of large-scale conservation in Southeast Asia. It is the largest protected area in Myanmar and its size is augmented by its contiguity with other protected areas. Such protection on a landscape scale is critical for globally threatened wildlife with large home ranges, including the Asian Elephant, Tiger, and Rufous-necked Hornbill. HVWS contains an array of forest types and elevations, in turn providing habitat to a diverse assemblage of wildlife. The inclusion of a substantial portion of the unprotected floodplain (the hole in the doughnut) would greatly strengthen its OUV by preserving a vast central seasonally-flooded grassland (second only in size to the Tonle Sap in Cambodia) that can support high densities of charismatic megafauna.

Hukaung Valley Wildlife

Among the animals found here are tigers, clouded leopard, golden cat, Asiatic black bear, elephants, macaques, gibbons, great hornbills, green peafowl, barking deer, samar deer, and dhole. A survey of animals in the early 2000s estimated that “probably fewer than a hundred tigers remain in the valley.”

According to a report submitted to UNESCO: HVWS includes many highly threatened species. Its size and connection to other protected areas makes HVWS particularly important for wide-ranging wildlife such as the Asian Elephant, Tiger, and Rufous-necked Hornbill. The Hoolock Gibbon and Shortridge’s Langur are also present (Brockelman and Geissmann 2008). More than 400 species of birds have been documented, including the White-bellied Heron. HVWS also contains the Burmese Peacock Softshell Turtle, which is endemic to Myanmar. The conservation value of HVWS would be greatly increased by extending the boundary to cover the northern part of the floodplain. Inclusion of this area would be particularly significant for waterbirds and Indian Water Buffalo. [Source: Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar]

Species of high conservation importance in HVWS include (Myanmar Biodiversity 2012): Mammals: Endangered: Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus), Dhole (Cuon alpinus), Hog Deer (Axis porcinus), Indian Water Buffalo (Bubalus arnee), Tiger (Panthera tigris), Hoolock Gibbon (Hoolock spp.), Shortridge’s Langur (Trachypithecus shortridgei); Vulnerable: Clouded Leopard (Neofelis nebulosa), Himalayan Black Bear (Ursus thibetanus), Gaur (Bos gaurus), Sambar (Rusa unicolor).

Reptiles: Endangered: Burmese Narrow-headed Softshell Turtle (Chitra vandijki), Burmese Peacock Softshell Turtle (Nilssonia formosa), Keeled Box Turtle (Cuora mouhotii); Vulnerable: Asian Box Turtle (Cuora spp.), Asiatic Softshell Turtle (Amyda cartilaginea), Impressed Tortoise (Manouria impressa). Birds: Critically Endangered: White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) Endangered: Slender-billed Vulture (Gyps tenuirostris), White-rumped Vulture (Gyps bengalensis), White-winged Duck (Carina scutulata), Masked Finfoot (Heliopais personata), Green Peafowl (Pavo muticus); Vulnerable: Wood Snipe (Gallinago nemoricola), Lesser Adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus), Rufous-necked Hornbill (Aceros nipalensis)

Hukaung Valley Ecosystem, Poachers and Environmental Threats

Hukawang Valley Wildlife Sanctuary was established in April 2001. It covers about 2,500 square miles. Hunting is banned but goes on anyway. There are plans to add 5,500 square miles to the sanctuary, tripling it size, making it the largest tiger refuge in the world. In this area tiger hunting would be banned but the hunting of other animals for food would be allowed in “exclusion zones.” Animals such as tigers and leopard are hunted to supply body parts for the Chinese medicine market. Hunters are paid $8 for a bear foot which can be sold for hundreds and even thousands of dollars at restaurants in China. The major focus of conservation is not to get people to stop hunting for food but to get them stop hunting for profit. Hunters are encouraged not only to stop hunting tigers but also to stop hunting tiger prey such as sambar deer and wild boar, many of which have been killed to supply meat that feed an influx of gold miners to the area.

According to the report submitted to UNESCO: Its size makes HVWS an outstanding example of large-scale ecological processes. It contains multiple interacting ecosystems and biophysical processes, as well as substantial habitat for megafauna with large ranges. HVWS ranges in elevation from 170 meters to 3,225 meters. If it were extended to include about 500 square kilometers of floodplain north of the Chindwin, this criterion would be further strengthened by connecting the mountain forests to the valley grasslands. [Source: Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar]

Within HVWS, except for small areas impacted by artisanal mining, the habitat is generally in good condition. However, protection of commercially valuable wildlife is a challenge, due in part to its size. Although tiger conservation was a driving factor behind its creation, it currently has fewer than 50 individuals. Judging from a Landsat image taken in September 2013, there appears to be no significant human impacts in the proposed floodplain extension. This extension would contribute to the property’s wholeness by including the ranges of key species including waterbirds.

Concessions cover most of the floodplain and parts of HVWS itself. The Russian energy company Nobel Oil was granted oil exploration rights in 2008 to Block PSC-A, which covers a significant portion of HVWS. Since no extractive industries can be present within a WHS, this presents a significant barrier to its nomination as a WHS. Several large gold mines are present in the unprotected valley. The largest is in Shingbwiyang in the western part of the valley. Migrants engage in gold panning along the rivers, which typically involves the use of cyanide, mercury, or other toxic substances. Inmigration has also increased hunting for subsistence and commercial use. Agricultural plantation concessions are also present in the valley. The proposed extension was drawn to exclude any areas of apparent mining or agriculture.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: Myanmar Travel Information, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, The Irrawaddy, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, burmalibrary.org, burmanet.org, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2020