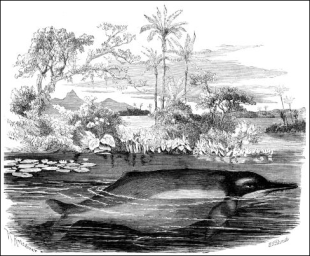

IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS

Irrawaddy dolphins (Scientific name: Orcaella brevirostris) are lightly colored and similar in appearance to beluga whales. They have a blunt, rounded head, and an indistinct beak. Their dorsal fin is short, blunt and triangular. In the wild, they have been seen spitting out streams of water, a unique and peculiar behavior. Contrary to what some people believe, these animals are not considered true river dolphin, but an oceanic dolphin because they can live in brackish water near coasts, river mouths and in estuaries. Even so they also live a considerable distance But they can also live [Source: WWF]

Irrawaddy dolphins are named after the Irrawaddy River in Myanmar bu are also found in the Mekong River in Laos and Cambodia, the Mahakam River in Kalimantan in Indonesia and the Padma River in Bangladesh. They were once found on the Chao Praya River, which flows through Bangkok, but haven’t been seen there in decades. The Yangtze river dolphin (baiji) is considered by some to be an Irrawaddy dolphin. It is now believed to extinct.

Irrawaddy dolphins prefer coastal areas, particularly muddy, brackish waters at river mouths and deltas, and do not appear to venture far offshore but occupy areas that pretty far upriver where the water is freshwater. They are typically found at depths of 2.5 to 18 meters (8.2 to 59 feet). Most sightings have been made within 1.6 kilometers of the coastline, but some have been reported in waters greater than five kilometers from shore. [Source: Melissa Koss; Lucretia Mahan; Sam Merrill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

See Separate Articles: RIVER DOLPHINS IN ASIA factsanddetails.com ; FRESHWATER DOLPHINS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Threatened Irrawaddy Dolphins in the Irrawaddy River

There are about 65 Irrawaddy dolphins left in Irrawaddy river according to the Wildlife Conservation Society and they face many challenges. Doug Clark wrote in the New York Times: “As the nation has modernized, the threats confronting the river dolphins have multiplied. Mercury from illegal gold mines, fertilizer from farms and industrial waste from factories have polluted the Irrawaddy. Increased ship traffic has harried the dolphins, and collisions are often fatal. Overfishing has devastated food sources, and the dolphins can get trapped in fixed gillnets and drown. Several are believed to have been electrocuted by fishermen illegally using car batteries to try to stun fish.. [Source: Doug Clark, New York Times, August 31, 2017]

”In 2012, the Wildlife Conservation Society reported finding 77 dolphins in the Irrawaddy. A 2016 survey found only 65. Since 2006, Myanmar’s government has established a special dolphin protective zone stretching about 50 miles north of Mandalay. But in the zone’s early years, there was little enforcement against electroshock fishing or pollution. Kira Salak wrote in National Geographic, “We are following the dolphins upriver when we pass some gill-net fishermen camped along the shore. This is one of the biggest threats to the Irrawaddy dolphin: Long nets are stretched across sections of the river to catch anything and everything that passes by—including dolphins.

Clark wrote: ”Recently, patrols have increased, and U Han Win, a researcher at Myanmar’s Department of Fisheries, says that dolphin conservation efforts have turned a corner. “The population decline of the dolphins would have been steeper if not for conservation,” he said. “Today, despite many challenges, the population is stable and doing better than it would have otherwise because of the conservation efforts.” Mr. Thin Myu, the fisherman, said that the increased patrols had made a positive difference. “Because of the patrols, now there are fewer electric fishermen,” he said, “and so the dolphins are working more cooperatively with us.”“

River Dolphins Help Irrawaddy Fishermen Fish

On the Irrawaddy (Ayerarwady) River in Myanmar, Irrawaddy dolphins engage in cooperative fishing with cast-net fishermen. Fishermen call the dolphins by tapping a lahai kway (wooden key) on the sides of their boats. One or two lead dolphins cooperate with the fisherman by swimming in smaller and smaller semi-circles herding the fish towards the shore. The dolphins dive with their flukes in the air just after the net is cast and create turbulence under the surface around the outside of the net. The dolphins seem to benefit from the fishing by preying on fish that are confused by the sinking net, and those trapped around the edges of the lead line or stuck in the mud bottom just after the net is pulled up. [Source: Melissa Koss; Lucretia Mahan; Sam Merrill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Doug Clark wrote in the New York Times: A few dozen fishermen are "left in Myanmar who know how to cooperate with Irrawaddy dolphins to fill their nets. Dwindling numbers of the endangered dolphins live in freshwater rivers and bays, including in Bangladesh and Indonesia, but only the population in Myanmar has been definitively documented as cooperating with humans. It is one of the few known instances of cooperation between humans and wild animals in the world." [Source: Doug Clark, New York Times, August 31, 2017]

” Irrawaddy dolphins have a long history with humans: A Chinese text dated to A.D. 800 noted, “The Pyu people traded this animal to China, and they named it the river pig.” When the dolphins stopped being prey and became partners is not known, but Mr. Thin Myu, 44, says he thinks it started in the times of his great-grandfather, who was a fisherman as well. Mr. Thin Myu said he had learned how to fish with dolphins from his brother and uncle. Back then, he told me, the fishermen had names for every dolphin, and the dolphins were so enthusiastic that they would spit water on fishermen sleeping in their boats at night to wake them to fish before dawn.”

Describing 42-year-old San Lwin fisherman, Kira Salak wrote in National Geographic, “ His father taught him to fish with dolphins when he was 16; the practice has been passed down for generations. Lwin's face, bronzed and creased from the sun, expresses a sort of reverence as he studies the silver waters for sight of a dolphin fin. "If a dolphin dies," he says, "it's like my own mother has died." [Source: Kira Salak, National Geographic, May 2006 \]

River Dolphins Help Fishermen Catch Fish Near Mandalay

Describing Lwin in action, Kira Salak wrote in National Geographic, “We reach the area of the river where Lwin says the dolphins congregate... Lwin and the other men tap small, pointed sticks against the sides of their canoes and make high-pitched cru-cru sounds. Several gray forms, gleaming in the sunlight, arch through the water toward us. One with a calf by her side spits air loudly through her blowhole. "Goat Htit Ma!" Lwin yells, pointing at her and smiling. "She's calling to us!" Goat Htit Ma has been fishing with them for 30 years, Lwin says. [Source: Kira Salak, National Geographic, May 2006 \]

Doug Clark wrote in the New York Times: “On a recent sweltering afternoon on the Irrawaddy River, about 10 miles upstream from Mandalay, a Burmese fisherman tapped a small teak dowel against the hull of his squat wooden boat, producing a xylophonic beat. Drawn by the drumming, the gray, melon-shaped forehead of an Irrawaddy dolphin — one of maybe 65 left in their eponymous waterway — breached the surface nearby. The dolphin was joined by about a dozen more, and together they began herding a school of thrashing baitfish toward the sun-weathered fisherman, who waited on the boat with a throw net. [Source: Doug Clark, New York Times, August 31, 2017]

”But before he could cast it, a barge loaded with pyramids of logs chugged past, causing the dolphins to dive and scattering the fish. Frustrated, the fisherman, U Thin Myu, began trying to drum up his partners again with the dowel. But a parade of barges from Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city, motored toward him and his wife, who was rowing at the stern.

”As he waited for the convoy of barges to rumble past his boat, Mr. Thin Myu patiently smoked a cheroot. After the convoy passed, he was again able to call the dolphins. He yelped at two he recognized, one by the distinctive white band around its neck, as if greeting old friends.

”One of the dolphins turned upside down, lifted its tail out of the water and slapped it down hard to the right — signaling to Mr. Thin Myu the location of their prey. With a shot-putter’s twist, he cast his net. The white mesh billowed open and came down over the roiling water. Another dolphin swam behind the splashing fish, herding them into the net. As Mr. Thin Myu reeled it in, the dolphins plucked at escaping fish. Mr. Thin Myu yanked a half-dozen small fish from the net, not yet enough for a full meal for his family. On better days, he would sell his excess catch at the market. But he never gave any to the dolphins — they had learned to cooperate with the fishermen independently, perhaps because they could steal fish tangled in the net.

“The fishermen splash their paddles to tell the dolphins they'd like to fish together. One dolphin separates from the group and begins swimming back and forth in large semicircles. It submerges again, reappearing less than ten feet (three meters) from our canoe, its tail waving with frantic urgency. Lwin winds up and tosses a lead-weighted net over the spot where the dolphin has shown its tail. The net spreads in the air like a great parachute, quickly sinking beneath the water. As Lwin slowly pulls it in, numerous silver fish flap in the strings. Lwin says the dolphins help themselves to any fish that escape the nets. \\

Challenges Faced by River Dolphins Helping Irrawaddy Fishermen

Doug Clark wrote in the New York Times: “The cooperation has frayed in the last decade as Myanmar has emerged from a half-century of isolation under a military junta. As the number of dolphins has dwindled, so has the number of fishermen who know how to work with them. According to the Wildlife Conservation Society, which helps Myanmar’s government manage the cetaceans, the number of cooperative fishermen has dropped to 65 — exactly the same as the number of Irrawaddy dolphins believed to still be in the river. Most of the fishermen are older, and finding new recruits is a challenge. [Source: Doug Clark, New York Times, August 31, 2017]

“Mr. Thin Myu trained his son to work with the dolphins, but the son left their village for Mandalay, so his wife now rows while he handles the net. Still, he has been tutoring five youths, trying to pass on the tradition. But with Myanmar’s economic development, he has noticed that young people find city jobs more alluring than trying to squeeze a living from the river.

The best hope to save both the dolphins and the fishermen may be ecotourism. Mr. Han Win, of the Department of Fisheries, estimated that 700 to 1,000 tourists come to see the dolphins every year. Most arrive on cruise ships and have little interest in the fishermen. But recently, the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries and Rural Development have begun to encourage smaller tours to accompany the fishermen, for which they are paid the equivalent of $20, a welcome sum in a country where the average worker makes $500 a month.

” U Kyaw Hla Thein, a project manager for the Wildlife Conservation Society, said, “Ecotourism encourages local fishermen to move away from harmful activities like electroshock fishing and maintain their traditional lifestyles. Dolphin conservation won’t be a success without ecotourism, and ecotourism won’t be a success without conservation.”

” Whether the dolphins and their partnership can endure in the face of Myanmar’s rapid modernization is unknown. Scientific study of the cooperative fishing phenomenon has been sparse. Brian Wood, an anthropology professor at Yale University, has researched similar instances of cooperation between humans and wild honeyguide birds to harvest honey in Tanzania. “As industrial lifestyles replace traditional ones across the world, humanity’s longstanding relationships with nature are disappearing,” Professor Wood said. “Once these relationships are lost, it’s almost impossible to get them back.” “The dolphins’ intelligence led them to partner with us originally because of the benefits they gained from us,” he added. “As they become less cooperative, they may be concluding it is no longer in their best interest to work as our partners.”

Irrawaddy river shark, image from Fishbase

Irrawaddy River Shark

The Irrawaddy river shark (Glyphis siamensis) is a species of requiem shark, family Carcharhinidae, known only from a single museum specimen originally caught at the mouth of the Irrawaddy River in Myanmar. A plain gray, thick-bodied shark with a short rounded snout, tiny eyes, and broad first dorsal fin, the Irrawaddy river shark is difficult to distinguish from other members of its genus without anatomical examination. Virtually nothing is known of its natural history; it is thought to be a fish-eater with a viviparous mode of reproduction. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as Critically Endangered, as its distribution is extremely limited and suffers heavy fishing pressure and habitat degradation. [Source: Wikipedia]

The only known Irrawaddy river shark was collected in the 19th century and described as Carcharias siamensis by Austrian ichthyologist Franz Steindachner, in Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien (volume 11, 1896). However, subsequent authors doubted the validity of this species, regarding it as an abnormal bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas), until in 2005 shark systematist Leonard Compagno recognized it as distinct member of the genus Glyphis.

The Irrawaddy river shark is found in the delta of the Irrawaddy River near Yangon, Myanmar, apparently inhabiting brackish water in a large, heavily silt-laden river lined with mangrove forests. The sole Irrawaddy river shark specimen is a 60 cm (24 in) long immature male, suggesting an adult length of 1–3 m (3–10 ft). Like other river sharks, its body is robustly built with a high back that slopes down to a broadly rounded snout shorter than the mouth is wide. The eyes are minute, and the nares are small and widely spaced. The mouth contains 29 tooth rows in the upper and lower jaws, and has short furrows at the corners. The upper teeth are broad, triangular, and upright, with serrated margins, while the lower teeth at the front are more finely serrated with a pair of small cusplets at the base.

The first dorsal fin is broad and triangular, originating over the rear pectoral fin bases with its free rear tip ending in front of the pelvic fin origins. The second dorsal fin is half as tall as the first, and there is no ridge between the dorsal fins. The trailing margin of the anal fin has a deep notch. The coloration is a plain grayish brown above and white below, without conspicuous fin markings. This shark most closely resembles the Ganges shark (G. gangeticus), but has more vertebrae (209 versus 169) and fewer teeth (29/29 versus 32–37/31–34). The small teeth of the Irrawaddy river shark suggests that it mainly preys on fish, while its small eyes are consistent with the extremely turbid water in which it hunts. Reproduction is presumably viviparous, with the young sustained by a placental connection, as in other requiem sharks.

Intensive artisanal fishing, mainly gillnetting but also line and electrofishing, occurs in the stretch of river where the sole Irrawaddy river shark specimen was caught. Habitat degradation poses a further threat to this shark, including water pollution and the clearing of mangrove trees for fuel, construction materials, and other products. This shark may be naturally rare, which along with its highly restricted range, probable overfishing, and loss of habitat, has led the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to list it as Critically Endangered. Despite fishing and scientific surveys in the area, no more Irrawaddy river sharks have been recorded in the hundred-plus years since the first.

New 'Bony-tongue' Fish Discovered in Myanmar

In May 2012, mongabay.com reported: “A new species of arowana, a highly valued aquarium fish, has been described from southern Myanmar. The description is published in the journal Aqua. The arowana, which is named Scleropages inscriptus, comes from the Tenasserim or Tananthayi River basin on the Indian Ocean coast of peninsular Myanmar. According to Tyson Roberts, the ichthyologist who described the species, Scleropages inscriptus is distinguished from the closely-related Asian arowana (Scleropages formosus) by the maze-like markings on its scales and facial bones. Like zebra, each fish is believed to have a unique pattern. [Source: mongabay.com, May 18, 2012]

Scleropages inscriptus is the first awowana recorded in Myanmar (formerly known as Burma), but according to Practical Fishkeeping, the fish has been known to fish hobbyists in Thailand for roughly a decade.Despite their large size and aggressive demeanor, arowana are popular aquarium fish. Asian species with distinctive coloration are particularly prized as "feng shui" fish believed to bring good luck. Some arowana may fetch tens of thousands of dollars at auction.Their popularity has lead to some species being overexploited. This, together with ongoing destruction of their rainforest habitat, has led conservationists to restrict the trade in some arowana species.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, The Irrawaddy, Myanmar Travel Information Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, burmalibrary.org, burmanet.org, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2020