JADE

Green jade plate

Myanmar government officials say jade has replaced rubies as the main attraction at a state-run auction held in Yangon with the majority of the buyers being Chinese. The Chinese have revered jade since Neolithic times. Archeological data shows that the ancient Chinese were using nephrite jade to make ornaments and weapons between 7000 and 8000 years ago. According to an ancient Chinese proverb: "You can put a price on gold, but jade is priceless."[Source: Fred Ward, National Geographic, September 1987; Timothy Green, Smithsonian magazine, 1984]

The Chinese word "yu which we translate as "jade" actually refers to any rock that is carved. Some 30 or 40 different kinds of mineral in China are called yu. Nephrite is known as "lao-yu" (“old jade”) or "bai-you" (“white jade”) and jadeite is known as "fei-cui-yu" (“kingfisher jade). John Ng, a jade specialist and author of Jade and You, told Smithsonian magazine, " The Chinese or Japanese have no hesitation in buying good pieces to give their families or friends for good luck. To the Asian, giving jade conveys a special feeling."According to the Chinese creation myth, after man was created he wandered the earth, helpless and vulnerable to attacks from wild beasts. The storm god took pity on him and forged a rainbow into jade axes and tossed them to the earth for man to discover and protect himself with.

See Separate Article JADE: SOURCES, MINERAL COMPOSITION, COLOR AND BUSINESS factsanddetails.com

Jade Carving in Myanmar

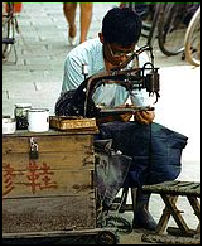

Up until about fifty years ago most carvers used the traditional method of drawing a bowstring back and forth to propel a drill with water and abrasive. Unlike ivory, jade is too hard to carve. It is shaped through cutting, grinding and polishing. Some craftsmen use electric tools, others use traditional tools such as pedal-operated treadle grinder, which has remained essentially unchanged for over a thousand years. One craftsman who prefers traditional tools told Smithsonian magazine, "We could use a diamond saw, but this traditional method gives him more control. There is less wastage, because you can cut a very thin slice."

Paul Watson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Child labor is an essential part of production at the bottom end of outdoor factories that surround Mandalay's jade market. Children huddle on their haunches around glowing embers in metal braziers, melting doping wax on the end of dop sticks, plucking small pieces of jade from a cup, and carefully placing them on the wax blobs. They blow gently to harden the seals and then hand the sticks up the line to other children. [Source: Paul Watson, Los Angeles Times, December 24, 2007]

On a recent day, one boy sat on the edge of a stool, stretching his leg to reach a wooden pedal that he pumped to spin a bamboo cylinder, wrapped in sandpaper, as he ground pieces of jade to a refined sheen. Once they'd done their best with small hands scraped by the grinders, the boys passed the jade along to men. It takes an experienced hand to get the shimmering polish that will bring the best price, a small piece of the profits that keep Myanmar's military in power. That can't be left in the shaky hands of children.

Burmese Jade, Hong Kong and China

sidewalk jade carver

Most of the world’s jadite is made into finished products in Hong Kong or Taiwan, mostly easy to replicate jewelry such as bangles and rings. Carving delicate figurines is time- consuming and expensive and there are only a few collectors that can afford the prices which often can be as high as $100,000 to $250,000. The highest price ever paid for jade jewelry was $9.39 million for necklace with 27 beads of emerald green jadeite. It was sold at a Christie's auction in Hong Kong.

The relation between the jade merchants of the Kachin State and the craftsman in the Yunnan Province endured for centuries but was broken by the Communist Revolution, when jade merchant set up shop in Hong Kong and carvers and crafts men migrated to Hong Kong from Beijing and Shanghai. Today, the quality of jade craftsmanship is much better in Hong Kong than it is in China or Taiwan.

Of the jadeite that reached China from Myanmar in the 1980s, about 40 percent of it was bought legitimately from auctions in Burma, 40 percent was smuggled through Thailand, and the remainder came directly from Burma to China's Yunnan province.

These days Chinese in Yunnan are buying more and more jade directly from the Kachin State. Much of the jade is purchased by buyers from China's National Arts and Crafts Import and Export Corporation in Beijing and the Guangdong Arts and Crafts Company in Guangzhou

Burmese Jade in Kachin State

The best jade deposits are located in the Kachin State, a semi-autonomous area in northern Myanmar. Most of jade here is found between the Burmese provinces of Chindwin and Uyu. Some of the jade is sold at government sponsored markets for "ridiculously high prices" but most of it is smuggled out." In the 1980s the top nephrite colors sold for $50 to $100 a kilogram, while a brilliant green, translucent jadeite cabochon (weighing little more than an ounce) could fetch more than $50,000. [Source: Fred Ward, National Geographic, September 1987, ╝].

The jadeite deposits are scattered over a large area between the Uyu and Chindwon rivers near the small town of Hpakan, about 200 miles north of Mandalay. The world's foremost deposit of jadeite is found in the bed of the Uru river and on the Tawmaw plateau.

The Kachin tribe has long felt that had the rights to the jade in their homeland, not the Myanmar government. Revenues from the jade mines once was the main source of income for the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), an insurgent group still active in the fight for independence from the Myanmar government even though it has a long-running ceasefire with the Myanmar government. [Source: Timothy Green, Smithsonian magazine]

The jade mines of Kachin State were controlled by Kachin chiefs until they were displaced by the KIO and its military faction, the Kachin Independence Army. Anyone who wants to jade from the region had to get a license from the KIO.

Describing a jade operation in Kachin state in the 1980s, Timothy Green wrote in Smithsonian magazine, "The mine owner, armed with his KIO license, employs a few miners and supplies them with food. They either work a small quarry—hauling out the jade boulders, which weigh anything from a couple of pounds to many tons, with the aid of water buffalos or oxen—or they scour streambeds. A small sector of the stream is dammed and then the diggers ferret through the exposed boulders for jade."

Burmese Jade Trade

Jade carver at work

The jadeite trade begins at the mines in Kachin, were low quality boulders are sold by the mines themselves to small time traders who go from to mine. Valuable boulders are taken from the mines to Hpakan, where the money from the sale is dived equally among the owner and miners, who in turn divide their share among themselves. The owner has to pay a five percent tax to the KIO, who mark the boulder as taxed. The price of the jade at this juncture is only ten percent of what it eventually becomes in Hong Kong. [Source: Timothy Green, Smithsonian magazine]

From Hpakan the jadeite is transported by ox or bullock cart to Mogaung, a larger town which has been the center of the jade for 200 years, when the Chinese in Yunnan began sending representatives here to buy jade for the Chinese Emperor's craftsmen. In Mogaung, the rough jade is sold to major traders who, for the most part, transport the jade along smuggling routes out of the country.

From Mogaung the jade can be taken about 70 miles to China, but much travels to Thailand, usually across 400 miles of rough country, occupied by warlords and hill tribe insurgents, who often exact tolls like petty Medieval lords. The jade couriers and armed caravans often pay for an escort by insurgent groups such as the Shan United Army, the Karen National Union, the Wa National Army or the remnants of the Kuomintang that came to Myanmar from China after the Chinese Revolution.

In the 1980s Most of the jade at the annual Burma Gems, Jade and Pearl Emporium came from two deposits in the Kachin State. The emporium accounts for only about 25 percent of the jade mined each year in Myanmar. The majority of it is smuggled out the country to Thailand—and more and more to China—on the backs of mules.

Jade Smuggling

"Smuggling," says Ward, "is more than the national pastime in Burma, albeit technically punishable by death. Most experts say that more than half the socialist's country's gross national product is black market. One U.S. Embassy official familiar with the problem jokes, 'Burma grows the tallest teak trees in the world. Not matter which way you cut one, it falls in China.' With jade, smuggling is the norm, even though it means lugging heavy boulders through the mountains and jungles to Thailand, at least a 12-day trek, using human porters. Everyone I saw agreed that well over half of the natural tonnage from the Mogaung area...is clandestinely carried from the Kachin State, through Shan State (where drug-snuggling warlords levy 15 percent safe-passage taxes) to northern Thailand." [Source: Fred Ward, National Geographic September 1987]

Shan tribesmen smuggle jade from Myanmar into Thailand along jungle trails on mules each packed with about 100 pounds of rough jade. It is estimated that $25 million worth of jade was smuggled from Myanmar in the 1980s into Thai border towns such as Mae Sot, Mae Hong Son or Mae Sai, where the jade is loaded into trucks and taken to Chiang Mae. [Source: Timothy Green, Smithsonian magazine]

In the 1980s Chinese in Yunnan province are buying more and more jade directly from the Kachin State. Much of the jade is purchased by buyers from China's National Arts and Crafts Import and Export Corporation in Beijing and the Guangdong Arts and Crafts Company in Guangzhou (Canton).

$8 Billion Jade Empire in Dominated by the Military and Chinese Tycoons

Shang-era jade tiger

Reporting from Hpakant, the center of Myanmar’s jade trade, Andrew R.C. Marshall and Min Zayar Oo of Reuters wrote: “Rare finds by small-time prospectors Tun pale next to the staggering wealth extracted on an industrial scale by Myanmar's military, the tycoons it helped enrich, and companies linked to the country where most jade ends up: China.[Source: Andrew R.C. Marshall and Min Zayar Oo, Reuters, September 29, 2013 ]

“Jade is not only high value but easy to transport. "Only the stones they cannot hide go to the emporiums," said Tin Soe, 53, a jade trader in Hpakant, referring to the official auctions held in Myanmar's capital of Naypyitaw. The rest is smuggled by truck to China by so-called "jockeys" through territory belonging to either the Burmese military or the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), both of whom extract tolls. The All China Jade Trade Association, a state-linked industry group based in Beijing, declined repeated requests for an interview.

After sending researchers to the area this year, the Harvard Ash Center published a report in July 2013 that put sales of Burmese jade at about $8 billion in 2011. That's more than double the country's revenue from natural gas and nearly a sixth of its 2011 GDP. "Practically nothing is going to the government," David Dapice, the report's co-author, told Reuters. "What you need is a modern system of public finance in which the government collects some part of the rents from mining this stuff."

“In a rare visit to the heart of Myanmar's secretive jade-mining industry in Hpakant, Reuters found an anarchic region where soldiers and ethnic rebels clash, and where mainland Chinese traders rub shoulders with heroin-fuelled "handpickers" who are routinely buried alive while scavenging for stones.

“At the top of the pecking order in Hpakant are cashed-up traders from China, who buy stones displayed on so-called "jade tables" in Hpakant tea-shops. The tables are run by middleman called laoban ("boss" in Chinese), who are often ethnic Chinese. They buy jade from, and sometimes employ, handpickers” who actually look for and find the jade.

Billions from “Unofficial Jade” from Myanmar Disappears

Reuters reported: “Almost half of all jade sales are "unofficial" - that is, spirited over the border into China with little or no formal taxation. This represents billions of dollars in lost revenues that could be spent on rebuilding a nation shattered by nearly half a century of military dictatorship. Official statistics confirm these missing billions. Myanmar produced more than 43 million kg of jade in fiscal year 2011/12 (April to March). Even valued at a conservative $100 per kg, it was worth $4.3 billion. But official exports of jade that year stood at only $34 million. [Source: Andrew R.C. Marshall and Min Zayar Oo, Reuters, September 29, 2013 ]

“Official Chinese statistics only deepen the mystery. China doesn't publicly report how much jade it imports from Myanmar. But jade is included in official imports of precious stones and metals, which in 2012 were worth $293 million - a figure still too small to explain where billions of dollars of Myanmar jade has gone. “Such squandered wealth symbolizes a wider challenge in Myanmar, an impoverished country whose natural resources - including oil, timber and precious metals - have long fuelled armed conflicts while enriching only powerful individuals or groups.

Since a reformist government took office in March 2011, Myanmar has pinned its economic hopes on the resumption of foreign aid and investment. Some economists argue, however, that Myanmar's prosperity and unity may depend upon claiming more revenue from raw materials. There are few reliable estimates on total jade sales that include unofficial exports.

The United States banned imports of jade, rubies and other Burmese gemstones in 2008 in a bid to cut off revenue to the military junta which then ruled Myanmar, also known as Burma. But soaring demand from neighbouring China meant the ban had little effect. After Myanmar's reformist government took power, the United States scrapped or suspended almost all economic and political sanctions - but not the ban on jade and rubies. It was renewed by the White House on August 7 in a sign that Myanmar's anarchic jade industry remains a throwback to an era of dictatorship. The U.S. Department of the Treasury included the industry in activities that "contribute to human rights abuses or undermine Burma's democratic reform process."

Hpakant, the Center of Myanmar’s Jade Mining

jade boulder

Reuters reported: “Hpakant lies in Kachin State, a rugged region sandwiched strategically between China and India. Nowhere on Earth does jade exist in such quantity and quality. "Open the ground, let the country abound," reads the sign outside the Hpakant offices of the Ministry of Mines. In fact, few places better symbolize how little Myanmar benefits from its fabulous natural wealth. The road to Hpakant has pot-holes bigger than the four-wheel-drive cars that negotiate it. During the rainy season, it can take nine hours to reach from Myitkyina, the Kachin state capital 110 kilometers (68 miles) away. [Source: Andrew R.C. Marshall and Min Zayar Oo, Reuters, September 29, 2013 ]

“Non-Burmese are rarely granted official access to Hpakant, but taxi-drivers routinely take Chinese traders there for exorbitant fees, part of which goes to dispensing bribes at police and military checkpoints. The official reason for restricting access to Hpakant is security: the Burmese military and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) have long vied for control of the road, which is said to be flanked with land-mines. But the restrictions also serve to reduce scrutiny of the industry's biggest players and its horrific social costs: the mass deaths of workers and some of the highest heroin addiction and HIV infection rates in Myanmar.

“Twenty years ago, Hpakant was controlled by KIA insurgents who for a modest fee granted access to small prospectors. Four people with iron picks could live off the jade harvested from a small plot of land, said Yitnang Ze Lum of the Myanmar Gems and Jewellery Entrepreneurs Association (MGJEA) in Myitkyina.

“There are also "obvious" links between jade and conflict in Kachin State, said analyst Richard Horsey, a former United Nations senior official in Myanmar. A 17-year ceasefire between the military and the KIA ended when fighting erupted in June 2011. It has since displaced at least 100,000 people. "Every Kachin feels passionately that their state's resources are being taken away," a leading Myitkyina gem trader told Reuters on condition of anonymity. "But we're powerless to stop them." "Such vast revenues - in the hands of both sides - have certainly fed into the conflict, helped fund insurgency, and will be a hugely complicating factor in building a sustainable peace economy," Horsey said.

“The mines were closed in mid-2012 when the conflict flared up again. Myanmar's military shelled suspected KIA positions; the rebels retaliated with ambushes along the Hpakant road. Thousands of people were displaced. Jade production plunged to just 19.08 million kg in the 2012/13 fiscal year from 43.1 million kg the previous year. But the government forged a preliminary ceasefire with the Kachin rebels in May, and some traders predict Hpakant's mines will re-open when the monsoon ends in October.

Jade Mining in Hpakant

Andrew R.C. Marshall and Min Zayar Oo of Reuters wrote: “Foreign companies are not permitted to extract jade. But mining is capital intensive, and it is an open secret that most of the 20 or so largest operations in Hpakant are owned by Chinese companies or their proxies, say gem traders and other industry insiders in Kachin State. "Of course, some (profit) goes to the government," said Yup Zaw Hkawng, chairman of Jadeland Myanmar, the most prominent Kachin mining company in Hpakant. "But mostly it goes into the pockets of Chinese families and the families of the former (Burmese) government." [Source: Andrew R.C. Marshall and Min Zayar Oo, Reuters, September 29, 2013 ]

“Other players include the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd (UMEHL), the investment arm of the country's much-feared military, and Burmese tycoons such as Zaw Zaw, chairman of Max Myanmar, who made their fortunes collaborating with the former junta. Soldiers guard the big mining companies and sometimes shoot in the air to scare off small-time prospectors. "We run like crazy when we see them," said Tin Tun, the handpicker.

Twenty years ago, Hpakant was controlled by KIA insurgents. A 1994 ceasefire brought most of Hpakant back under government control, and large-scale extraction began, with hundreds of backhoes, earthmovers and trucks working around the clock. "Now even a mountain lasts only three months," said Yitnang Ze Lum. Many Kachin businessmen, unable to compete in terms of capital or technology, were shut out of the industry. Non-Kachin workers poured in from across Myanmar, looking for jobs and hoping to strike it rich.

“When operations are in full swing, the road to Hpakant is clogged with vehicles bringing fuel in and jade out. Such is the scale and speed of modern extraction, said Yitnang Ze Lum, Hpakant's jade could be gone within 10 years.

Life of Myanmar Jade Pickers: Heroin, Hope and Danger

Reuters reported: “Tin Tun picked all night through teetering heaps of rubble to find the palm-sized lump of jade he now holds in his hand. He hopes it will make him a fortune. It's happened before. "Last year I found a stone worth 50 million kyat," he said, trekking past the craters and slag heaps of this notorious jade-mining region in northwest Myanmar. That's about $50,000 (30,975 pounds) - and it was more than enough money for Tin Tun, 38, to buy land and build a house in his home village. [Source: Andrew R.C. Marshall and Min Zayar Oo, Reuters, September 29, 2013 ]

“The handpickers are at the bottom of the heap - literally. They swarm in their hundreds across mountains of rubble dumped by the mining companies. It is perilous work, especially when banks and slag heaps are destabilized by monsoon rain. Landslides routinely swallow 10 or 20 men at a time, said Too Aung, 30, a handpicker from the Kachin town of Bhamo. "Sometimes we can't even dig out their bodies," he said. "We don't know where to look." In 2002, at least a thousand people were killed when flood waters inundated a mine, Jadeland Myanmar chairman Yup Zaw Hkawng told Reuters. Deaths are common but routinely concealed by companies eager to avoid suspending operations, he said.

“The boom in Hpakant's population coincided with an exponential rise in opium production in Myanmar, the world's second-largest producer after Afghanistan. Its derivative, heroin, is cheap and widely available in Kachin State, and Hpakant's workforce seems to run on it. About half the handpickers use heroin, while others rely on opium or alcohol, said Tin Soe, 53, a jade trader and a local leader of the opposition National League for Democracy party. "It's very rare to find someone who doesn't do any of these," he said.

“Official figures on heroin use in Hpakant are hard to get. The few foreign aid workers operating in the area, mostly working with drug users, declined comment for fear of upsetting relations with the Myanmar government. But health workers say privately about 40 percent of injecting drug users in Hpakant are HIV positive - twice the national average. Drug use is so intrinsic to jade mining that "shooting galleries" operate openly in Hpakant, with workers often exchanging lumps of jade for hits of heroin.

“Soe Moe, 39, came to Hpakant in 1992. Three years later, he was sniffing heroin, then injecting it. His habit now devours his earnings as a handpicker. "When I'm on (heroin), I feel happier and more energetic. I work better," he said. The shooting gallery he frequents accommodates hundreds of users. "The place is so busy it's like a festival," he said. Soe Moe said he didn't fear arrest, because the gallery owners paid off the police.”

China Companies Make a Killing on Myanmar Jade

“UMEHL is notoriously tight-lipped about its operations. "Stop bothering us," Major Myint Oo, chief of human resources at UMEHL's head office in downtown Yangon, told Reuters. "You can't just come in here and meet our superiors. This is a military company. Some matters must be kept secret." This arrangement, whereby Chinese companies exploit natural resources with military help, is both familiar and deeply controversial in Myanmar. [Source: Andrew R.C. Marshall and Min Zayar Oo, Reuters, September 29, 2013 ]

In 2012, “protests outside the Letpadaung copper mine in northwest Myanmar triggered a violent police crackdown. The mine's two operators - UMEHL and Myanmar Wanbao, a unit of Chinese weapons manufacturer China North Industries Corp - shared most of the profits, leaving the government with just 4 percent. That contract was revised in July in an apparent attempt to appease public anger. The government now gets 51 percent of the profits, while UMEHL and Myanmar Wanbao get 30 and 19 percent respectively.

“China's domination of the jade trade could feed into a wider resentment over its exploitation of Myanmar's natural wealth. A Chinese-led plan to build a $3.6 million dam at the Irrawaddy River's source in Kachin State - and send most of the power it generated to Yunnan Province - was suspended in 2011 by President Thein Sein amid popular outrage. The national and local governments should also get a greater share of Kachin State's natural wealth, say analysts and activists. That includes gold, timber and hydropower, but especially jade.

“A two-week auction held in the capital Naypyitaw in June sold a record-breaking $2.6 billion in jade and gems. But jade tax revenue in 2011 amounted to only 20 percent of the official sales. Add in all the "unofficial" sales outside of the emporium, and Harvard calculates an effective tax rate of about 7 percent on all Burmese jade. It is, on the other hand, highly lucrative for the mining companies, whose estimated cost of production is $400 a ton, compared with an official sales figure of $126,000 a ton, the report said. "Kachin, and by extension Myanmar, cannot be peaceful and politically stable without some equitable sharing of resource revenues with the local people," said analyst Horsey.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, The Irrawaddy, Myanmar Travel Information Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, burmalibrary.org, burmanet.org, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2014