ANIMISM IN MYANMAR

Thagyamin Nat

An estimated 3 percent of the population, mainly in more isolated areas, adhere solely to animistic religious beliefs. Many Burmese Buddhists—and Muslim and Christians too—also believe in spirits called nats. A variety of religious practitioners are associated with the animistic beliefs of most Buddhists, including spirit dancers who become possessed by spirits and may engage in healing and fortune-telling. There are also astrologers, other types of healers, tattoists with occult knowledge, and magicians.

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “Animism is a generic term used to describe the myriad religious beliefs and practices that have been utilized in small-scale human societies since the beginning of the prehistoric era and is the earliest identifiable form of religion found in Burma. This is not an unexpected occurrence because animist beliefs and practices have been found among early human societies in almost every country of the world. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

“Animism is a belief that spirits exist and may live in all things, sentient and non-sentient. The world is thought to be animated by all sorts of spirits that may intervene negatively or positively in the affairs of men. Although spirits may live in all things, every object does not harbor a spirit. If there were a spirit in everything, the daily activities of mankind would be seriously disrupted because a spirit would have to be addressed or placated at every step in a day's activities.” =

“Animism, a generic term for the Small Religions, is a substratum of beliefs out of which the Great Religions have developed. It is a useful term to describe all of the small religions that vary greatly in the specifics of their practice. However, there are general characteristics that are easily recognized. Since animism is based upon the worship of individuals who once lived in addition to spirits that dwell in specific environmental locations, there are a myriad number of spirits. These spirits change in name and function in different physical environments. Consequently, the names of the spirits change from valley to valley, from one village to another or from one small group to the next. The worship of numerous spirits differs markedly from the great religions, which usually have one all encompassing god or a limited pantheon of gods. By comparison, in Burma and Thailand there is a spirit attached to every parcel of land. =

“Since Animism is typically practiced by non-literate groups of people, a written record of their theology or literature doesn't exist. Practices or beliefs are passed down orally from shaman to apprentice. Since it is important for the shaman to preserve the correct order in which chants and genealogies must be recited, shaman in several societies have independently invented what scholars have come to refer to as "memory boards". These are boards on which there are a series of symbols or marks that assist in proper recollection and recitation. These boards have been found in many small-scale societies including those in Southeast Asia, particularly in Borneo and as far away as Easter Island. These boards, although often undecipherable to the uninitiated, are important because they are examples of the first form of writing. *

Spirits (Nats) in Myanmar

Yokkaso Nat

Burmese believe in nats—"terrestrial spirits that influence human affairs." Many Burmese still worship them vigorously and believe that Nats can bring luck and prosperity to the those who appease and worship them and bring danger and misfortune to those who do not respect them or don't believe in them. The origin of word "Nat" is unclear. It may be derived from the Hindu term “Natha.” which means lord. savior or protector. There are also ghosts, demons and spirits and goblins in the forest, caves and natural features that are also capable of causing harm. There male and female nats. Most are malevolent. The worst and most powerful nats are ones that evolved from people who died from unusually painful deaths.

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “ Spirits by their very nature are thought to be normally invisible and to assume visible form only on rare occasion. Therefore, it is a challenge for anyone to contact a specific spirit and be absolutely sure that the correct spirit was contacted and was present. Therefore, throughout the world, spirits are often assigned a contact point where they may be enticed for consultation. Salient features of the landscape often become the "home" of a spirit by assignment. Spirits are thought to live, for example, on the highest peak in a mountain range or at the odd bend in the creek but not in every stone or drop of water. If a landscape is devoid of a salient feature, such as is the case with a flat rice field, one is created by assignment such as building a simple shrine in the northeast corner of the field. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

“That the spirits have a recognized "home" is important since the relevant spirit or spirits must be located and consulted before important decisions are made or an activity undertaken. Location as well as "presence" is of vital importance in animism because the spirit must be agreeably enticed to the location so that the request will meet with a positive response. A home or locus for consulting ancestor spirits is often created in animist societies by carving a generic but gendered human image and wrapping it in a garment or with possessions identified with the deceased. Gifts of all kinds, often of luxury goods, are ritually presented to the image when it may be wrapped in any of the deceased individual's possessions.” =

Types of Spirits in Myanmar

Bo Bo Gyi Nat in Sule Pagoda in Yangon

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “ In virtually all societies that practice animism, there are three broad categories of spirits: Spirits of the Ancestors, Spirits of the Locale or Environment (often referred to as genie of the soil) and Spirits of Nature or Natural Phenomenon. Those individuals who were important in this life, such as patriarchs, matriarchs, clan leaders, political leaders, or chiefs, are honored after their death because it is believed that if they were powerful in this life then they will be powerful in the afterlife and consequently they should be consulted. Security for the living is achieved and maintained by consulting these important ancestor spirits to receive advice on major decisions and assistance to bring them to fruition. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

“Spirits of the locale or environment include, for example, the spirit of the mountain, the waterfall, the great tree or of each plot of land. In inhabited areas in Burma and especially within villages or towns, almost every large tree has a spirit shelf on which food and drink is placed to please the spirit and thus assure its blessings. The small wayside shrines, typically containing no images that are found along thoroughfares as well as in remote locations throughout Burma are dedicated to the spirit(s) of that area, that tract of land or that city plot. =

“The Spirits of Natural Phenomenon are consulted as needed. These include the sun, moon, storms, hurricanes, typhoons, winds and earthquakes. These spirits represent the uncertainty of the world; that which is beyond the understanding and complete control of the living.” =

Buddhism, Hinduism and 37 Nats

Burmese Buddhists believe that the Nat world is for the this world. Buddha is for next world. Anthropologist link the worship of nats with crisis management. "Buddhism," wrote W.E. Garret in National Geographic "allows for no spirit of god worship, but people cling to animism that predated the arrival of Buddha's teachings. One Burmese tries to explain it to me: "Buddhism is concerned with the hereafter; we placate and propitiate the nats in this world." [Source: W.E. Garret, National Geographic, March 1971.]

Most Buddhist pagodas contain shrines and alters for nats as well figures related to Buddhism. People make offering to nats. Many homes have small foot-high-houses nailed onto the wall, which are used to house nats.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: “As in many Southeast Asian cultures, so too in Myanmar an ancient animistic belief system exists side by side with the official main religion, in this case Theravada Buddhism. Spirits are called nat in Myanmar, and the nat spirits were already canonised very early on. There are altogether 37 nat. They may be the spirits of exceptional, deceased persons or localised variants of Hindu deities. One example of the latter is Deva Indra Sakka, the king of the nat, who can be recognised as Indra, the head of the Hindu pantheon. The nat are traditionally the protectors of homes, villages, towns, mountains, and forests, although they have also been given Buddhist connotations. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki]

37 Nats

Burmese place special importance on 37 Nats, Kira Salak wrote in National Geographic: “In the 11th century, King Anawrahta established the Theravada school of Buddhism as Myanmar's primary religion. When his attempts to eliminate nat worship, considered a form of occultism not accepted by Buddhist scriptures, proved fruitless, he decided to adapt it instead, creating an official pantheon of 37 spirits to be worshipped as subordinates of the Buddha. The result is that many Buddhist temples in Myanmar now have their own nat-sin, spirit house, attached to the main pagoda. Though people still worship spirits outside the official pantheon, the 37 enjoy a VIP status, with traveling troupes of dancers, singers, and musicians reenacting the human stories of the spirits' tumultuous lives and violent deaths. [Source: Kira Salak, National Geographic, May 2006]

Nats and their Hindu inspirations: Thurathadi (Saraswati), Sandi (Chandi), Paramethwa (Shiva), Mahapeinne (Ganesha), Beikthano (Vishnu)

During the 11th century King Anawrahta of Pagan was converted to Buddhism which then became the official religion of the entire kingdom. The ancient Myanmar people believed that the forces of nature were driven by spirits. Every spirit maintains a territory. Finally, the number of the Nats was set in the twelfth century by King Anawrahta in order to contain a cult that Buddhism had failed to eliminate. Even today, Myanmar people keep alive their belief in the 37 Nats. Myanmar Travel Information]

The 37 Nats are: ; 1) Thagya (Indra or Sakra); 2) MahaGiri (Lord of the great mountain); 3) Hnamadawgyi (Great royal sister of Magagiri); 4) Shwe Nabe (Lady Golden Sides); 5) Thon Ban Hla (Lady Three Times Beautiful); 6) Toungoo Mingaung (King Mingaung of Taungoo); 7) Mintara (King Hsinbyushin); 8) Thandawgan (The Royal Secretary to Taungoo Minkaung); 9) Shwe Nawrahta (The young prince drowned by King Shwenankyawshin); 10) Aung Zawmagyi (Lord of the White Horse); 11) Ngazishin (Lord of the five white elephant); 12) Aungbinle Hsinbyushin (Lord of the white elephant from Aungbinle);

13) Taungmagyi (Lord of Due South); 14) Maung Minshin (Lord of the North); 15) Shindaw (Lord Novice); 16) Nyaung-gyin (Old man of the Banyan tree); 17) Tabinshwehti (King of Myanmar between 1531-50); 18) Minye Aungdin (Brother-in-law of King Thalun); 19) Shwe Sit thin (Prince) son of Saw Hnit); 20) Medaw Shwedaw (Lady Golden Words); 21) Maung Po Tu (Shan Tea Merchant); 22) Yun Bayin (King of Chiengmai); 23) Maung MinByu (Prince MinByu); 24) Mandalay Bodaw (Lord grandfather of Mandalay); 25) Shwebyin Naungdaw (Elder Brother Inferior Gold);

26) Shwebyin Nyidaw (Younger Brother Inferior Gold); 27) Mintha Maungshin (Grandson of Alaung Sithu); 28) Htibyusaung (Lord of White Umbrella); 29) Htibyusaung Medaw (Lady of White Umbrella); 30) Pareinma Shin Mingaung (The Usurper Mingaung); 31) Min Sithu (King Alaung Sithu); 32) Min Kyawzwa (Prince Kyawzwa); 33) Myaukpet Shinma (Lady of the North); 34) Anauk Mibaya (Queen of the Western Palace); 35) Shingon (Lady Hunback); 36) Shigwa (Lady Bandy-legs); 37) Shin Nemi (Little lady with the flute); ;

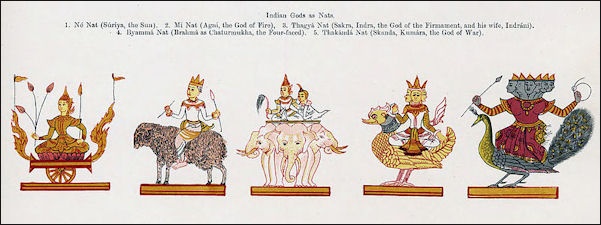

Nats and their Hindu inspirations: Thuriya (Suriya), Agni, Thagyamin (Indra), Byamma (Brahma) and Thukanda (Skanda)

Religious Practitioners and Rituals in Burmese Animism

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “Animism is typically practiced through rituals that are performed by a specially trained practitioner who serves as an intermediary between a person or group and the spirit to be consulted. The term shaman - the word used for such an individual in tribes living along the American Northwest Coast - is today widely employed by academics to identify such individuals wherever they appear in the world. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

“This practitioner is called to perform a ritual at an auspicious location in which he entices the appropriate spirit or spirits to appear and cooperate by flatteringly calling them by name, performing their favorite music or songs, recounting their good deeds and offering them the things that they enjoyed when alive, such as food, drink (frequently alcohol), or things that have an appealing fragrance such as flowers or incense. These "objects of enticement" are considered by outsiders to be the Arts of Animism. Since animist rituals often do not require an image, these arts frequently consist of the objects used for enticement such as fine textiles, fine basketry or fine ceramics. Typically these items are the best available, expensive, newly made for the ceremony, or at least refurbished since it would be offensive to offer old clothing or stale food to a respected individual. Once the shaman is convinced the desired spirit is present and in an agreeable mood, he goes into trance and consults with the spirit concerning the critical matter at hand. He then comes out of trance and shares the wishes of the spirit(s) with his client(s).” =

“There are typically three categories of questions that are asked: those that involve the security of the group or person; the fertility of humans, livestock and crops; and the health of the group or the individual. All three categories of questions have to do with everyday life, the here and now, and unlike the "Great Religions", little attention is focused on the afterlife.” =

“The practitioners of animism, the shaman or mediums, do not belong to an organized clergy but, instead, learn the rituals and the practices of animism by having been an apprentice or an acolyte to another shaman. The specialized task of the shaman requires them to communicate with spirits, whether male or female, while in a trance. Consequently, an individual of ambiguous gender is well suited to speak intimately with spirits of either gender. Therefore, shaman tends to be either effeminate males or masculine females who at their will are capable of going into trance.” =

Animist Art in Myanmar

nat ceremony in 1959

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “Art objects used in animism are typically made of perishable materials. The images are often of wood, cane, feathers, leather, and other materials such as unfired clay that easily disintegrate. Due to humidity, bacteria, and the foraging of animals and insects, these art forms do not last for long periods. Art forms made of perishable materials are suitable for animist ritual since the animist aesthetic places importance on the new and beautiful because the end goal is to please and attract the spirits. The sentiment here is that attractive gifts should be new and not secondhand. Therefore, old images that have been used previously are frequently repainted, re-dressed or made anew. At times, the "art objects" are discarded after a ritual since the objects have served their purpose of attracting the spirit and the spirit by its very nature of being a spirit can not take the objects away. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

“Animist art obects are created in almost any form. The images may be anthropomorphic, or just an uncut slab of rock. The object may be adorned or unadorned. In Burma, the major Animist spirits were transformed into the Pantheon of the 37 Nats during the Pagan Period. The earliest known images of the brother and sister nats, Min Mahagiri and his Sister, who lead the pantheon, were painted on two planks hewn from a their sacred tree that had been thrown into the Irrawaddy and had floated down the Irrawaddy to Pagan. =

Nat Centers and Festivals

Burmese believe that nats must be appeased at stated times and places to avoid misfortune. Mount Popa is the home of of nats. At Mount Popa there are transvestite shaman—wives of nats — who serve as intermediaries to the gods. They go into trances. People throw money at them. Many of transvestites have said they had dreams when they were young in which a nat came to them and asked them to be their wife.

An 80 year medium named old Daw Thein Khin often presides over ceremonies to placate evil nats. National Geographic editor Bryan Hodgson observed her offering rum to honor the Brother Nats of Taungbyon who are particularly strong because they had been killed by having their testicles crushed.

In the Kachin region "manaus" or nat festivals are sometimes held. During these festivals the Kachin—many of them Christians— gather wearing their most beautiful and colorful costumes. In a large gathering 29 water buffalo may be sacrificed—one buffalo for each of the 28 nats honored and one for all the nats together. Before the sacrifice offerings of rice, eggs and wine and bamboo tubes are made. The buffalo are then ritually slaughtered, and their skulls and horns are placed on X-shaped poles. To the music of gongs and flutes the Kachin do snake dances around the poles with the buffalo skulls, as well as around nat poles which are reminiscent of totem poles. During the snake dance, which are led by chiefs wearing feathered head dresses, the dancers often go into trances.

During some spirit possession rituals hunks of raw meat are clutched in the teeth of the possessed.

Mt. Popa

Mt Popa

The center of the nat cult is Mount Popa, near Pagan. Mount Popa (near the town of Kyuak Padaung, 50 kilometers from Pagan) is a 4,900-foot-high lava plug (the hardened lava remnants of volcano that eroded away millions of years ago) that has become the center of “nat” (spirit) worshiping in Myanmar. Perched on a rocky outcrop at the top of the mountain is a temple where the nats are worshiped. Thousand of pilgrims climb the dizzying stairway, especially in May, to pay homage to the nats that reside in the temple, which also has a famous monastery, troops of monkeys and snake charmers.

Mt. Popa is sort like Mt. Olympus for nats (spirits of ancient ancestors) who dwell in various parts of the mountain. The evidence of these beliefs is abundant in the form of "nat shrines", legends, rituals, ceremonial offerings, annual representative festivals, and the never- ending stream of pilgrims and believers in mysticism. In many places there are "nat trees" which have prayer rags tied to their branches, Tibetan style, and have alters at the bases of their trunks. Popa today is one of the most popular pilgrimage spots in the country.

The Mt. Popa Nat Festival honors Mt Popa's presiding nats: Mae Wunna and her sons Min Lay and Min Gyi. Devotees of Manuha Paya celebrate a large paya pwe (or pagoda festival) on the full moon of Tabaung (which falls between February an March. depending on the Lunar Calendar).

Nat Pwe, Spirit Rituals

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: “The nat cult has many features that resemble shamanism. In the Burmese nat cult, the priestesses, as well as priests, fall into a trance, during which they act as oracles or healers to the community that commissioned the ritual. An event of this kind is called nat pwe (pwe = play or performance). Despite the fact that the cult is very archaic, the nat priests are organised, which is rather rare in Southeast Asian animistic systems. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki ]

“The main annual nat event is held in Taungbyon near Mandalay, where dozens of nat pwe groups gather for their rituals. These rituals can also be performed at other times, for example in a Buddhist temple compound, or in private homes or shops, which are converted into nat shrines with temporary altars and statuaries.

“The ceremony is accompanied by a small, traditional percussion orchestra, which signals the event with its dynamic music. Fruits, food, cigarettes, rum, and beer are offered to the nat statues, after which the nat pwe gradually starts. One or more nat priests with their assistants arrive on the scene, dancing in a relaxed manner and partaking of the offerings.

Mt Popa nats

“The principal priest performing the actual ritual wears a simple garment, such as a shawl, or a headgear, indicating which nat he or she will be in contact with during the ritual. The priest dances ecstatically, repeating simple steps and moving arms and hands in a manner typical of Burmese dance. However, in nat pwe, as in so many possession rituals around the world, dancing skill is of only secondary importance.

“The priest sings while dancing and recites scenes from the life of the nat being portrayed. At the climax of the ritual, the priest falls into a trance and “becomes” the nat in question. Still dancing or sometimes whirling half-consciously on the ground, the priest announces prophecies to the assistants, who interpret them to the audience.

“Nat pwe ceremonies can still be seen frequently, and a short nat ritual is almost always part of a traditional theater or dance performance in Myanmar. A performance usually begins with the dance of the nat priestess. In classical productions, lacking the element of trance, this dance is performed by a skilful professional dancer and it is more refined than in the authentic, often powerful, nat pwe rituals.”

Nat Ka Daws (Transvestite Spirit Wives) and Irrawaddy River Spirit

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “In Burma, animism has developed into the cult of the Thirty-Seven Nats or spirits. Its spirit practitioners, known as nat ka daws, are almost always of ambiguous gender, and are thought to be married to a particular spirit or nat. Despite their physical appearance and costume, however, they may be heterosexual with a wife and family, heterosexual transvestites, or homosexual. Being a shaman is most often a well-respected profession because the shaman performs the functions of both a doctor and a minister, is often paid in gold or cash, and is often unmarried with the time and money to care for their aging parents. Shamans who combine their profession with prostitution lose the respect of their clients - a universal conflict and outcome. The reputation of Burmese nat-ka-daws has been generally damaged by this conflict. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

Tabinshwehti Nat

Kira Salak wrote in National Geographic: “Numerous spirits live along the river, and worshipping them has become big business...I stop near a small village called Thar Yar Gone to witness a nat-pwe, or spirit festival. Inside a large thatch hut, musicians play loud, frenetic music before a crowd of rowdy onlookers. On the opposite end of the hut, on a raised stage, sit several wooden statues: nat, or spirit, effigies. I pass through the crowd and enter a space underneath the stage, where a beautiful woman introduces herself as Phyo Thet Pine. She is a nat-kadaw, literally a "spirit's wife"—a performer who is part psychic, part shaman. Only she isn't a woman—she is a he, a transvestite wearing bright red lipstick, expertly applied black eyeliner, and delicate puffs of powder on each cheek. Having traveled to the village by oxcart, smears of dirt covering my sweaty arms and face, I feel self-conscious before Pine's painstakingly created femininity. I smooth my hair and smile in apology at my appearance, shaking Pine's delicate, well-manicured hand. [Source: Kira Salak, National Geographic, May 2006 ]

“Nat-kadaws are more than just actors; they believe that the spirits actually enter their bodies and possess them. Each has an entirely different personality, requiring a change in costume, decorations, and props. Some of the spirits might be female, for whom the male nat-kadaw dons women's clothing; others, warriors or kings, require uniforms and weapons. To most Burmese, being born female rather than male is karmic punishment indicating grave transgressions in former lifetimes. Many Burmese women, when leaving offerings at temples, pray to be reincarnated as men. But to be born gay—that is viewed as the lowest form of human incarnation. Where this leaves Myanmar's gay men, psychologically, I can only imagine. It perhaps explains why so many become nat-kadaws. It allows them to assume a position of power and prestige in a society that would otherwise scorn them.

“Pine, who is head of his troupe, conveys a kind of regal confidence. His trunks are full of make-up and colorful costumes, making the space under the stage look like a movie star's dressing room. He became an official nat-kadaw, he says, when he was only 15. He spent his teenage years traveling around villages, performing. He went to Yangon's University of Culture, learning each of the dances of the 37 spirits. It took him nearly 20 years to master his craft. Now, at age 33, he commands his own troupe and makes 110 dollars for a two-day festival—a small fortune by Burmese standards.

Nat Ka Daw (Transvestite Spirit Wife) Ritual

Kira Salak wrote in National Geographic: Pine, a ka daw, “outlines his eyes with eyeliner and draws an intricate mustache on his upper lip. "I'm preparing for Ko Gyi Kyaw," he says. It is the notorious gambling, drinking, fornicating spirit. The crowd, juiced on grain alcohol, hoots and shouts for Ko Gyi Kyaw to show himself. A male nat-kadaw in a tight green dress begins serenading the spirit. The musicians create a cacophony of sound. All at once, from beneath a corner of the stage, a wily-looking man with a mustache bursts out, wearing a white silk shirt and smoking a cigarette. The crowd roars its approval. [Source: Kira Salak, National Geographic, May 2006 ]

Nat Kadaw dressed as U Min Gyaw at a nat festival in Mingun in 1989

“Pine's body flows with the music, arms held aloft, hands snapping up and down. There is a controlled urgency to his movements, as if, at any moment, he might break into a frenzy. When he talks to the crowd in a deep bass voice, it sounds nothing like the man with whom I just spoke. "Do good things!" he admonishes the crowd, throwing money. People dive for the bills, a great mass of bodies pushing and tearing at each other. The melee ends as quickly as it had erupted, torn pieces of money lying like confetti on the ground. Ko Gyi Kyaw is gone.

“That was just the warm-up. The music reaches a feverish pitch when several performers emerge to announce the actual spirit possession ceremony. This time Pine seizes two women from the crowd—the wife of the hut's owner, Zaw, and her sister. He hands them a rope attached to a pole, ordering them to tug it. As the frightened women comply, they bare the whites of their eyes and begin shaking. Shocked as if with a jolt of energy, they start a panicked dance, twirling and colliding into members of the crowd. The women, seemingly oblivious to what they are doing, stomp to the spirit altar, each seizing a machete.

“The women wave the knives in the air, dancing only a few feet away from me. Just as I am considering my quickest route of escape, they collapse, sobbing and gasping. The nat-kadaws run to their aid, cradling them, and the women gaze with bewilderment at the crowd. Zaw's wife looks as if she had just woken from a dream. She says she doesn't remember what just happened. Her face looks haggard, her body lifeless. Someone leads her away. Pine explains that the women were possessed by two spirits, ancestral guardians who will now provide the household with protection in the future. Zaw, as the house owner, brings out two of his children to "offer" to the spirits, and Pine says a prayer for their happiness. The ceremony ends with an entreaty to the Buddha.

“Pine goes under the stage to change and reappears in a black T-shirt, his long hair tied back, and begins to pack his things. The drunken crowd mocks him with catcalls, but Pine looks unfazed. I wonder who pities whom. The next day he and his dancers will have left Thar Yar Gone, a small fortune in their pockets. Meanwhile, the people in this village will be back to finding ways to survive along the river.

Taungbyon Nat Festival

Nat festival

“The main annual nat event is held in Taungbyon near Mandalay, where dozens of nat pwe groups gather for their rituals. The festival is usually held during the month of August. This festival includes the following matters: 1) Preparation for the Ritual; 2) The Offerings; 3) The Orchestra; 4) The Possession. [Source: Myanmar Travel Information]

The Nat Pwe is usually held for three days. The first day is for the Summoning the Nats. The second day is the Nats' feast. The third is the day for the Nats' departure. Devotees from all over Myanmar come to this special festival and offer their donations and enjoy themselves with the blessings of the spirits. They pray for prosperity, fame and luck for the next coming year.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, The Irrawaddy, Myanmar Travel Information Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, burmalibrary.org, burmanet.org, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2019