POLITICS AND ISLAM IN MALAYSIA

Ian Buruma wrote in The New Yorker, “The real Malay dilemma today is that democrats need the Islamists: Malay liberals and secular Chinese and Indians cannot form a governing alliance without religious and rural Malays. And the only serious contender who can patch over the differences between secularists and Islamists for the sake of reform is Anwar, a liberal Malay with impeccable Muslim credentials. “He is our last chance,” Zaid told me, as he celebrated the victory of PAS in Kuala Terengganu. When I repeated this to Anwar, he looked thoughtful and said, “Yes, and that’s what worries me.” [Source: Ian Buruma, The New Yorker, May 19, 2009]

Malaysia’s Islamic politics were strongly shaped by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, who ruled for 22 years until 2004. To counter the opposition Islamist party PAS, Mahathir expanded the religious bureaucracy and strengthened its authority at both state and federal levels. Malaysia identifies itself as an Islamic state, unlike neighboring Indonesia, which did not adopt Islam in its constitution. [Source: Jane Perlez, New York Times, February 19, 2006 ]

Mahathir’s successor, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi,, an Islamic scholar, was initially expected to ease the growing influence of religious courts, but he took few concrete steps to limit their power. His government instead enforced religious sensitivities, including shutting down a newspaper that published the Danish cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. Tensions between civil and religious authority were highlighted in 2006 when Islamic officials overrode a family’s wishes and conducted a Muslim burial for a national hero whom relatives said remained Hindu. After public controversy, the prime minister ordered a review of policies related to religious conversion, signaling possible future reforms.

RELATED ARTICLES:

POLITICS IN MALAYSIA: LEADERS, ETHNICITY, RELIGION, SYMBOLS, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

POLITICAL PARTIES IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA: SYMBOLS, CONSTITUTION, LEADERSHIP factsanddetails.com

GOVERNMENT BRANCHES OF MALAYSIA, PRIME MINISTER AND LEGISLATURE factsanddetails.com

ELECTIONS IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

MAHATHIR MOHAMAD: HIS LIFE, VIEWS, CHARACTERS, OUTRAGEOUS STATEMENTS factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA UNDER MAHATHIR MOHAMAD factsanddetails.com

NAJIB RAZAK: LIFE, POLITICAL CAREER, SCANDALS factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA UNDER PRIME MINISTER NAJIB RAZAK 2009-2018 factsanddetails.com

1MDB SCANDAL: BILLIONS, BIRKIN BAGS, CELEBRITIES, JHO LOW, JAILTIME FOR NAJIB factsanddetails.com

ANWAR IBRAHIM'S LIFE AND POLITICAL CAREER factsanddetails.com

ANWAR IBRAHIM'S TRIALS, LEGAL PROBLEMS AND TIME IN JAIL factsanddetails.com

ANWAR IBRAHIM FINALLY BECOMES PRIME MINISTER factsanddetails.com

Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) — Islamic Party of Malaysia

The Parti Islam se-Malaysia (PAS) is the primary Islamic party of Malaysia. It considers itself the guardian of Islamic values in Malaysia which it says have been lost in the pursuit of wealth and economic prosperity. It wants to make sharia (Muslim law) the law of the land. .It is known in English as the Islamic Party of Malaysia or the Pan-Malaysia Islamic Party is Malaysia. Internationally, PAS is affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood.

Malaysia’s first Muslim political party was founded in 1948 by Abu Bakar al-Bakir as the country moved toward independence. In 1951, Ahmad Fuad bin Hassan established the Parti Islam SeMalaysia (PAS), which later became a major political force and is now one of the country’s main opposition parties. In the early 2000s, PAS had 800,000 registered members, half of them women. [Source: Ahmad Yousif, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

PAS has traditionally been strong in northern Peninsular Malaysia in Kedah, Perlis and Pahang states and is the dominate party in Kelantan, where it has passed laws banning alcohol sales, gambling and unisex hair salons. The part also gained significant support in rural Perak and Pahang during the 2022 general election and the 2023 state elections. This surge in support was dubbed the "Green Wave."

Following the 2022 general election, PAS became the largest individual party in the federal Dewan Rakyat (Malaysia’s parliament) , holding 43 of the 222 seats. The party has also elected parliamentarians or state assembly members in 11 of the country's 13 states. PAS was a founding and key component of the Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition, which took power amid the 2020–21 Malaysian political crisis. Currently, the party governs either solely or in coalition with other parties in the states of Kelantan, Terengganu, Kedah, and Perlis. Previously, it was a coalition partner in the state governments of Penang and Selangor, as part of the federal opposition, from 2008 to 2018. [Source: Wikipedia]

PAS's Position on Sharia and Ethical Issues

PAS wants Sharia (Islamic law) to be the land in moral matters for Muslims in Malaysia and supports varying degrees of segregation of the sexes but it doesn't necessarily endorse stoning, caning and amputations but it did in the past. Non-Muslims fear they will be affected by Islamic law. PAS has said it supports the Taliban in Afghanistan. In a major speech in August 2004, the leader of PAS said it was committed to making Malaysia a strict Islamic state.

PAS has a reputation for being honest and not corrupt. It has renounced terrorism and said it is committed to democracy. However it did declare jihad over American attacks in Afghanistan. It is supported by middle class Malays, professionals and university graduates as well as farmers, fishermen and working class Muslims. Some have called the party Taliban Lite.

PAS has is struggled to broaden its appeal. The party has long campaigned to turn Malaysia into an Islamic state, which turns many non-Muslims off. "What we're doing now is trying to narrow the gap between PAS and the non-Malay, non-Muslim community," PAS deputy president Nasharudin Mat Isa told Reuters. "We're going to defend the culture of all minority groups, the language, the schools." In efforts to form an alliance with the Chinese-dominated parties, PAS has reached out to the Chinese community in the areas they control by giving them money for social programs.

In the early 2000s, "a more moderate face of PAS has emerged," Abdul Razak Baginda of the Malaysian Strategic Research Center told the New York Times. "This is a clear sign that even PAS recognizes that, in Malaysia, a moderate approach is necessary. Adopting a more radical and extreme view of Islam will not resonate with the public." Chandra Muzaffar, a leading political analyst in Kuala Lumpur, said this is true of Southeast Asia in general. Although Islamic radicalism has become more prevalent in recent years, it has not gained significant public support. "This would go against the way Islam is practiced in this region," Chandra said. "Malaysian Muslims, like those in Indonesia and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, are not comfortable with this rigid, dogmatic approach to religion." [Source: Seth Mydans, New York Times, December 6, 2005]

Islamic Rule in Kelantan

PAS has been in power in Kelantan in northeast Malaysia since 1990, Liau Y-Sing of Reuters wrote: Due to its population make-up — 94 percent of its 1.4 million people are Muslims — Islam plays a big role in Kelantan. Historically part of the Thai kingdom of Patani and the ancient seat of Islamic civilization, Kelantan has an appearance of piety and austerity. Many villagers live in rickety wooden homes and till the land, go to sea or sell farm produce for a living. With its strong emphasis on the afterlife, the state has more Islamic religious schools than other parts of Malaysia. Gambling joints, cinemas and nightclubs are not allowed in the state and alcohol can only be sold to non-Muslims. Dikir barat, a group recital of catchy poems, is said to be a typical pastime. But some locals say real entertainment — illicit drugs and cheap sex — abounds across the Thai border. [Source: Liau Y-Sing, Reuters, February 5, 2008]

Ian Buruma wrote in The New Yorker, ““Kelantan has hardly any huge buildings. Everything in the state capital, Kota Bharu, near the border with Thailand, is built on a modest scale... Islamic laws have been introduced there for Muslims, though they are not always enforced. Muslims cannot drink alcohol. The lights must stay on in movie houses, and only morally acceptable films can be shown. (Some movie houses have gone out of business.) But nobody has been stoned for adultery or had limbs amputated.[Source: Ian Buruma, The New Yorker, May 19, 2009 ]

“Few people in Kelantan, even the Chinese, openly complain about the PAS government. Non-Muslims don’t feel hampered by religious rules that don’t apply to them, and the lack of corruption is widely acknowledged. Still, given the chance, many young people leave for Kuala Lumpur. Several young Malays told me that it was “no fun” living in a place where you can get arrested for buying a beer. “This is a place for old men,” an unemployed building contractor said. “They can sit around and pray all day.”

Softening of Islamic Rule in Kelantan

After PAS’s poor showing in the 2004 elections, Seth Mydans wrote in the New York Times, “Alcohol, dancing, movies and gambling are still forbidden today in Kelantan, and most women cover their heads in compliance with local government directives. On a billboard advertising shampoo in the state capital, Kota Bharu, a row of seven smiling women hide their hair under Muslim head scarves. But the Kelantan government has softened its religious pronouncements and has begun to loosen its bans on evening entertainment, allowing traditional theater and shadow-puppet plays. It has even staged a rock concert and a fashion show. [Source: Seth Mydans, New York Times, December 6, 2005 +=+]

“It appears to have stopped trying to enforce one of its more showy decrees - separate supermarket lines for women and men. In the Pacific Hypermarket, as in other markets in Kota Bharu, men and women stand together at checkout counters, ignoring little stick-figure pictures overhead that indicated who should go where. "At first, the authorities enforced the rule," said Rusmini Hakim, assistant manager of cashiers at the market. "But people made a fuss. And now no one comes around any more to check on us." +=+

Razak Ahmad of Reuters wrote: “PAS, long tagged as a conservative Islamic party, did not have any appeal beyond its rural Malay strongholds until 2005 when the reformers started winning key posts in party elections on a pledge to moderate the party to broaden its appeal. The strategy paid off, with PAS gaining support from mainly non-Muslim ethnic minority Chinese and Indians in general elections in 2008. [Source: Razak Ahmad, Reuters, June 6, 2009]

“PAS is the smallest party in the three-member Alliance holding just 24 of the opposition's 83 seats in Malaysia's 222-seat parliament, but is the biggest in terms of membership. Observers note a growing assertiveness and awareness in PAS of its kingmaker role.

Honest Islam Versus Ruling Party Money in Kelantan

Liau Y-Sing of Reuters wrote: The political battle lines are clear in Malaysia's predominantly Muslim state of Kelantan: religion versus money. The federal government has promised millions of dollars of investment in a bid to win the state back from an Islamist party that has ruled the rural backwater for 18 years. But for many of Kelantan's voters, material wealth — or the lack of it — may not count for as much as religious piety and a corruption-free environment. [Source: Liau Y-Sing, Reuters, February 5, 2008 ~~]

"Islamic rule is very generous," said Mrs Tan, a tiny 50-year old ethnic Chinese, as she peered over her half-moon glasses while poring over newspapers in her modest auto spare parts store. "They follow religious laws. There is no corruption and they are more fair and honest." Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi's Barisan Nasional coalition is targeting poor voters in Kelantan in a bid to shake them off from the grip of the fundamentalist Parti Islam se-Malaysia (PAS) that governs the northeastern state.

“A small farming area of 1.4 million people, Kelantan has seen few fruits of the country's rapid economic growth in the last decade. In 2004, a tenth of its people lived in poverty, the third highest rate among Malaysian states, official figures show. The government hopes to change this under a $34 billion plan to create a farming, energy and tourism hub encompassing the states of Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang and parts of Johor. The blueprint — the first large scale development involving the country's east coast — pitches a vision of Kelantan as a booming farming centre with thriving goat, fish and kenaf farms. ~~

“But for many the "purist" appeal of the PAS remains the biggest draw. "Kelantan is strongly religion-orientated," said Syed Husin Ali, an opposition party leader and former university professor specializing in rural poverty. "As far as they are concerned, what is important is not material things, but the spiritual. PAS, of course, appeals to this kind of religious conservatism." ~~

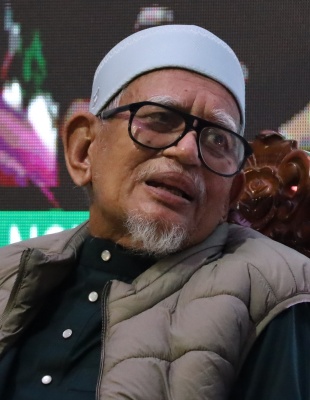

Central to PAS's appeal is its 77-year old spiritual leader,Nik Aziz Nik Mat, who is also chief minister of Kelantan. An iconic figure garbed in flowing robes and a skullcap, the bearded Egyptian-educated scholar is seen as morally upright and accessible to the common folk, living in a modest brick and wooden home in a traditional Malay village. This is in stark contrast to what many locals see as the opulent lifestyles of the ruling coalition's leaders.

"A more effective approach for Barisan Nasional is quite simply to spend more time, more money and more planning based on Kelantan's situation," said Shamsul Amri Baharuddin, the founding director of the government-created Institute of Ethnic Studies. "They should not use the approach that is seen from outside." Ultimately, the outcome of the battle for Kelantan may be decided by indifferent locals such as toy store owner Lim. "It doesn't matter who wins," he said over a simple meal of fish and rice in a cramped corner of his shop. "No one will help us, we just have to make our own living."

Efforts by Mahathir and the UMNO to Undermine PAS

The UMNO (United Malays National Organization), which traditionally dominated Malaysian politics, promoted a moderate version of Islam, known as “hadhari,” as an alternative to the more conservative approach associated with PAS. Leaders framed elections as a choice between different interpretations of Islam. [Source: Seth Mydans, New York Times, December 6, 2005; The Economist , May 29, 2003]

During the 1990s and early 2000s, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad took a firm stance against Islamic political rivals. He linked PAS to extremism and terrorism, especially after the September 11 attacks, and some PAS members were arrested. Supporters of PAS argued these actions were politically motivated. Mahathir also expanded state involvement in Islamic affairs by building mosques, strengthening religious education and courts, supporting Islamic finance, and placing religious schooling under government oversight. While these measures aimed to counter Islamist criticism, they also helped PAS gain sympathy among some voters

In August 2001, Malaysian authorities detained several people under the Internal Security Act (ISA), including Nik Adli Nik Abdul Aziz, the son of PAS spiritual leader Nik Abdul Aziz. Police said the detainees were linked to a militant group that had received training in Afghanistan and was involved in violent crimes. The ISA allowed indefinite detention without trial, prompting criticism from opposition leaders and human rights groups, who argued the arrests were politically motivated and called for open court trials. Government officials denied targeting PAS, stating that action was taken for national security reasons. [Source: AFP, August 5, 2001]

Tensions between authorities and opposition groups continued in later years. In September 2007, police fired on rioters at a political rally in Kuala Terengganu, wounding two members of an Islamist opposition party in what opposition figures described as one of the country’s most serious episodes of political violence in recent times.

PAS's Ups and Downs in Malaysian Elections

In parliamentary elections in 1999 PAS tripled the number of seats it held in the Malaysian parliament to 27 and took control of state governments, including the oil rich province Terengganu. After the election the Mahathir government began to view PAS as a legitimate threat and stepped up their effort to present its self a voice or reasonable Islam and characterize PAS as fanatics. In Terengganu PAS has tried to get a larger share of the state’s oil money which goes primarily to the national government but was blocked from doing so and punished by having the oil money they usually get denied them and put into a special fund controlled by the national government.

In the election in March 2004, PAS collapsed, with its number of seats in parliament dropping from 27 to 7. It lost control of Terengganu, which it gained in 1999. With Mahathir gone and the Islamic-school-trained Abdullah in power the PAS could not attack UNMO like it had in the past. PAS retained control of Kelantan, but number of seats it held in the local parliament was reduced to 24, compared to 39 it held in 1990. Malaysia’s ruling coalition held 21 in the local parliament. A special election was called when one of the PAS. A loss of that seat would have left PAS with a majority of just one seat.

In May 2013, the the Barisan Nasional (BN, National Front) coalition of Prime Minister Najib Razak won a majority of seats in the lower house of the Parliament but otherwise looked weak in an election that could be viewed as a kind of failure for both sides as the BN failed to improve its tenuous position and Anwar Ibriham’s opposition coalition failed to take a majority and did not improve much on the progress it made in 2008. The BN won 133 seats (60 percent of the seats) in the 222-member parliament. Anwar’s Pakatan Rakyat (People’s Pact) took 89 seats (40 percent of the seats). [Source: AFP, May 5, 2013]

PAS Joins a Coalition with Reformist Anwar

In March 2008, PAS joined a three-party opposition alliance led by reformist Ibrahim Anwar, including the pro-Chinese Democratic Action Party (DAP) and Parti Keadilan, led by Anwar’s wife, which made unprecedented gains against the ruling UMNO party in general elections Anwar's three-party opposition alliance won an unprecedented 82 of Parliament's 222 seats — 30 short of a majority — as well as control of five states. [Source: Associated Press, July 15 2009; Jalil Hamid, Reuters, June 4, 2005]

Among the opposition groups, PAS drew strong support from ethnic Malays, who are defined as Muslim by the state, and was often viewed by the government as the most concerning rival. Although the Chinese-backed DAP held more parliamentary seats, PAS’s Islamic platform generated greater political debate. PAS aligned with Keadilan before Anwar’s release from prison in 2004, but both parties performed poorly in that year’s elections, prompting renewed discussions about closer cooperation with DAP despite lingering concerns among DAP supporters over PAS’s goal of establishing an Islamic state.

In 2005, PAS invited Anwar to help unify the fragmented opposition and mount a stronger challenge to Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi’s multiracial ruling coalition. PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang told party members that Anwar’s “charisma and credibility” could strengthen the opposition and publicly accepted him as a leader. At the same time, Hadi emphasized that PAS would not compromise on its objective of creating an Islamic state based on Shariah law, describing the party as being at a “critical crossroads” guided by the Qur’an. Anwar, who did not attend the party assembly, argued that PAS was often misunderstood in the West as extremist, a characterization Hadi also rejected.

After the 2008 general election, PAS continued to demonstrate its regional strength but faced signs of declining support. In July 2009, the party retained a legislative seat in its Kelantan stronghold, winning a by-election by just 65 votes—a sharp drop from its 1,352-vote margin the previous year. Analysts suggested the narrower victory reflected renewed momentum for the ruling coalition among Malay voters. PAS officials countered that holding the seat despite government campaign promises and development pledges was a significant achievement, underscoring the party’s continued relevance in Malaysian politics.

Although Islam is the official religion, Malaysia is not an Islamic state. Some Muslims have argued that religious freedom includes the right to create Islamic legal and economic systems and potentially an Islamic state. These concerns increased in 1999 when PAS formed state governments in Kelantan and Terengganu. The federal government has promoted a moderate interpretation of Islam while maintaining the existing political structure and has taken strong action against suspected Islamic militants, including detentions without trial under the Internal Security Act. [Source: Ahmad Yousif, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

Leadership of PAS

As of 2025, the President of PAS is Abdul Hadi Awang. He has held the position since 2002. The spiritual leader is Hashim Jasin, whoh as held the position since 2016. The influential leader of PAS, Fazil Noor, died in 2002, when Abdul Hadi Awang took over. The former spiritual leader of PAS NokAziz Nik Mat, who was also chief minister of Kelantan, made headlines when he advocated polygamy to rescue unmarried women from becoming "aged virgins." Despite this many in Kelantan respected him. Reuters reported: “An iconic figure garbed in flowing robes and a skullcap, the bearded Egyptian-educated scholar is seen as morally upright and accessible to the common folk, living in a modest brick and wooden home in a traditional Malay village.”

In June 2009, the reformist wing of PAS suffered a setback when vice president Husam Musa lost an internal leadership contest to conservative incumbent Nasharudin Mat Isa, who was supported by influential clerics and party president Abdul Hadi Awang. The outcome suggested that PAS members favored a cautious approach to change and that religious leaders remained highly influential within the party. Nasharudin’s victory raised speculation about possible cooperation between PAS and the ruling UMNO, though he reaffirmed PAS’s commitment to the opposition People’s Alliance while remaining open to dialogue with other groups. Analysts viewed the results as a sign that PAS was not ready for rapid reform. [Source: Razak Ahmad, Reuters, June 6, 2009 ]

Ian Buruma wrote in The New Yorker about his meeting with , I met the PAS vice-president, Husam Musa at the party headquarters: “Husam, an economist by training, is not an imam but one of the new breed of professionals in Islamist politics. He was polite, if a little defensive. On the question of an Islamic state, he said this goal was often misunderstood: “We don’t mean a state ruled by clerics but one guided by the holy books. Without the books, we’d be like UMNO and just grab the money. The difference between us and them is that we believe we will be judged in the afterlife.” .[Source: Ian Buruma, The New Yorker, May 19, 2009 ]

“He said that Islam was “pro-progress,” and that American democracy was a good model. (“Unfriendly people will accuse me of being pro-American for making this statement.”) He also said that discriminating against ethnic minorities was “un-Islamic,” as was government corruption. “People should be treated the same, and that includes the freedom of religion,” he said. What about Muslims “” were they free to renounce their faith? He averted his eyes. “I have my own opinion about that, but I will reserve it,” he said. “Media in Malaysia will interpret it in the wrong way. Everything here is turned to politics.” He used “politics” as a pejorative term. “I am not a politician,” he said. “I’m a Muslim activist.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Common

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026