GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA

The government of Malaysia is a federal parliamentary democracy with a constitutional monarch (somewhat similar to the one in Great Britain) and a prime minister. The prime minister is the leader of the party or coalition with the most seats in Parliament. General elections to elect members of have to be called within a five year period. The ceremonial monarch is a king. The Malays, which make up about 53 percent of the country's population, have the most representatives in the parliament and state assemblies.

From 1981 to 2003, the Prime Minister of Malaysia was Mahathir Mohamed, who was unquestionably the most powerful and influential political figure in Malaysia, substantially influencing economic and social development. He was prime minister for a second time from 2018 to 2020. He turned 100 in 2025. From the 1960s to 2018, the political coalition led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), Mahathir's political party, governed the country. Some observers contend that corruption is problematic in politics, but international organizations that focus on corruption generally suggest that while Malaysian politics and business exhibit a degree of corruption, which can peak such as in 1MDB scandal, Malaysia has less corruption than most countries in the world.

Local divisions: 13 states (11 states on Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah and Sarawak on Borneo) and two federal territories. Nine of the states are led by sultans and four by governors. The capital is Putrajaya not Kuala Lumpur. The 13 states (negeri-negeri, singular - negeri) are: Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Malacca, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Perak, Perlis, Pulau Pinang, Sabah, Sarawak, Selangor, Terengganu. The one federal territory (Wilayah Persekutuan) has three components, Kuala Lumpur, Labuan, and Putrajaya. [Source: CIA World Factbook]

RELATED ARTICLES:

GOVERNMENT BRANCHES OF MALAYSIA, PRIME MINISTER AND LEGISLATURE factsanddetails.com

MONARCHY OF MALAYSIA: SULTANS, POWER, RELEVANCY factsanddetails.com

DUTIES, RESPONSIBILITIES, SELECTION AND CROWNING OF THE MALAYSIAN KING factsanddetails.com

ELECTIONS IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

MAHATHIR MOHAMAD: HIS LIFE, VIEWS, CHARACTERS, OUTRAGEOUS STATEMENTS factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA UNDER MAHATHIR MOHAMAD factsanddetails.com

POLITICS IN MALAYSIA: LEADERS, ETHNICITY, RELIGION, SYMBOLS, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

POLITICAL PARTIES IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

POLITICS, ISLAM AND PAS (ISLAMIC PARTY OF MALAYSIA) factsanddetails.com

How Government Works in Malaysia

Malaysia is technically regarded as a constitutional monarchy nominally headed by paramount ruler (commonly referred to as the King) and a bicameral Parliament consisting of a nonelected upper house and an elected lower house. Functionally most power resides with the executive, and the government could most accurately be described as "prime ministerial government." All Peninsular Malaysian states have hereditary rulers (commonly referred to as sultans) except Malacca (Malacca) and Pulau Pinang (Penang); those two states along with Sabah and Sarawak in East Malaysia have governors appointed by government; powers of state governments are limited by federal constitution; under terms of federation, Sabah and Sarawak retain certain constitutional prerogatives (e.g., right to maintain their own immigration controls). [Source: CIA World Factbook]

In keeping with the concept of Parliamentary Democracy which forms the basis of the government administration in Malaysia, the Federal Constitution underlines the separation of governing powers among the Executive, Judicial and Legislative Authorities. The separation of power occurs both at the Federal and State level in keeping with the concept of federalism which forms the basis of the government administration in Malaysia. The federal government has authority over external affairs, defense, internal security, and justice, except for civil law cases among Malays, other Muslims, and other indigenous peoples, which are adjudicated under Islamic and traditional law. The federal government also has authority over federal citizenship, finance, commerce, industry, communications, transportation, and other matters.[Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale 2008; Malaysian Government]

States in Malaysia have their own constitutions and governments. Political institutions continue to evolve for many reasons, including recent emergence from colonialism, greater focus on economic rather than political development, and coexisting traditional and nontraditional authorities. Technically, all government acts are legitimized by the king’s authority, and the civilian and military public services officially owe their loyalty to the king and hereditary rulers. However, the king only acts on the advice of both parliament and the cabinet, and in practice the prime minister is the most powerful political authority. [Source: Library of Congress, 2006]

Power and Leadership in the Malaysian Government

Diane K. Mau wrote in Governments of the World: “In legal principal, the constitution, which is supreme, defines the parameters and mechanisms of government and the division of powers and responsibilities between levels of government and between the government and the people. The courts act as the guardian of the constitution. The constitution designates parliament as the law-making body of government, whose acts are sanctioned by the royal assent of the monarch, based on the advice of the elected government. [Source: Diane K. Mau, Governments of the World: A Global Guide to Citizens' Rights and Responsibilities, Thomson Gale, 2006]

“In actual practice, Malaysia has always had a strong executive, because of the electoral dominance of the ruling coalition and rigid party discipline. Parliament has correctly been viewed as a rubber-stamp institution: With little discussion it automatically passes the bills put forward by the governing executive. Early on it provided a forum for the opposition, but increasingly the opposition has been stymied by rule changes limiting its time, and government control of the media has muted its parliamentary voice. Parliament is held in such low regard that members of parliament, and especially ministers, constantly have to be reminded that they must attend sessions.

“Despite a strong tilt in favor of the power of the executive, when Mahathir became prime minister in 1981, he felt threatened by the monarch and hemmed in by the judiciary. He thus engaged in two quite controversial contests for power between 1983 and 1989. The constitutional monarch is expected to take the advice of the government and not withhold his assent to bills, except in cases involving the rulers, in which his consent is necessary. However, the constitution assumed but nowhere stated that the monarch must accept advice and must not withhold royal assent. Faced with the likelihood that the next king would be the Sultan of Johor, widely viewed as unpredictable, the government decided to close all the ambiguities allowed by convention through a constitutional amendment. However, the outgoing king opposed the amendment and, with the approval of the Conference of Rulers, withheld his assent, thus creating the very constitutional crisis that was feared. After months of tensions, with the rulers intransigent and the government attacking them with exposés of royal extravagance and threats to end the feudal system, a compromise was reached that filled most of the legal loopholes, but left the royal houses with some face-saving measures.

“A more serious crisis occurred with Mahathir's destruction of the independence of the judiciary in 1987 and 1988. Mahathir, who could impose his will over the cabinet and parliament, became increasingly frustrated at having his actions blocked at times by the courts, and he accused the courts of infringing on executive power, trying to usurp power, and thwarting the will of the majority. When his political party, UMNO, split and its vast corporate assets were up for grabs, Mahathir began to shear away the powers of the courts.

“In March 1988, with little publicity, parliament quickly passed the Federal Constitution (Amendment) Act 1988. This far-reaching amendment changed the political system. Henceforth, the powers of the judiciary would no longer be embedded in the constitution but rather conferred by parliament through statutes. Further, the High Courts were stripped of the power of judicial review (the power to pronounce on the constitutionality and legality or otherwise of executive acts). When the Supreme Court still seemed noncompliant, the Lord President was dismissed and five (of nine) Supreme Court judges were suspended. The revamped Court then voted to give the UMNO assets to Mahathir's "New UMNO" faction. Members of the Bar Council expressed shock at how easily the judiciary's constitutional protection was stripped.

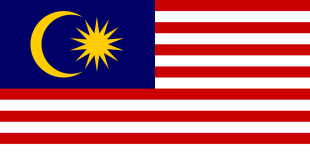

Symbols and Flag of Malaysia

The Malaysian flag: Known as the Jalur Gemilang (Stripes of Glory), it has 14 horizontal stripes of equal width: red (top) alternating with white (bottom); there is a blue rectangle in the upper, left corner bearing a yellow crescent and a yellow 14-pointed star. The 14 stripes stand for the equal status in the federation of the 13 member states and the federal government. The 14 points on the star represent the unity between these entities. Tthe crescent is a traditional symbol of Islam; blue symbolizes the unity of the Malay people and yellow is the royal color of Malay rulers. The design is based on the flag of the United States.

The Malaysian flag was adopted in 1963. The 14 stripes and 14-pointed star represent the 14 states that made up Malaysia at the time it was created in 1963. The flag is similar to the old Federation of Malaya flag which had 11 stripes. The Malaysian government encourages the flying of the Jalur Gemilang particularly during the Month of Independence in August as an expression of love, loyalty and pride for the country.

The coat of arms of Malaysia shows a 14-pointed star representing the 13 constituent states within the Federation of Malaysia together with the Federal Government, while the star and the crescent together symbolise Islam as the official religion of Malaysia. The five Kris represents the five former Unfederated Malay States (Johor, Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan and Terengganu). The left-hand division of the shield represents the state of Penang and the right-hand section shows the Malacca tree that depicts the State of Malacca. These two states formed part of the former Straits Settlements.

In the four equal sized panels in the centre, the colours black and white are colours of the State of Pahang; red and yellow are colours of the State of Selangor; black, white and yellow are the colours of the State of Perak; and red, black and yellow those of the State of Negeri Sembilan. These four States formed the original Federated Malay States. The three sections below represent the State of Sabah on the left and the State of Sarawak on the right. In the centre is the hibiscus, the national flower. Flanking the shield are tigers, a design element retained from the earlier armorial ensign of the Federation of Malaya (and before that, of the Federated Malay States).

The motto in Romanised-script on the left and Jawi (Arabic) script on the right reads “Bersekutu Bertambah Mutu”, the Malay equivalent of “Unity is Strength”. The yellow colour of the scroll is the royal colour of the Rulers.

The tiger is the national symbol of Malaysia.

Rukunegara: Malaysia’s National Ideology

Malaysia’s national ideology, the Rukunegara was formulated with the purpose to serve as a guideline in the country’s nation-building efforts. The Rukunegara was proclaimed on August 31, 1970 by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong IV. [Source: Malaysian Government]

The pledge of the Rukunegara is as follows: “Our Nation, Malaysia is dedicated to: Achieving a greater unity for all her people; maintaining a democratic way of life; creating a just society in which the wealth of the nation shall be equitably distributed; ensuring a liberal approach to her rich and diverse cultural tradition, and building a progressive society which shall be oriented to modern science and technology.

We, the people of Malaysia, pledge our united efforts to attain these ends, guided by these principles: 1) Belief in God; 2) Loyalty to King and Country; 3) Upholding the Constitution; 4) Sovereignty of the Law; and 5) Good Behaviour and Morality.

Malaysian National Anthem

“Negaraku” (“My Country”) has been Malaysia’s national anthem since 1957. It uses music adapted from the French melody “La Rosalie,” was originally the anthem of the state of Perak, and features lyrics by former Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman.

The anthem promotes unity and harmony among Malaysia’s diverse population. Under the National Anthem Act of 1968, it has three versions—full (royal), abridged, and short—each played in different circumstances. The full version is performed in the presence of the king. People are required to stand as a sign of respect when the anthem is played in public, and deliberate disrespect can result in fines or imprisonment.

The lyrics in Malay are:

Tanah tumpahnya darahku

Rakyat hidup bersatu dan maju

Rahmat bahagia Tuhan kurniakan

Raja kita selamat bertakhta

Rahmat bahagia Tuhan kurniakan

Raja kita selamat bertakhta.

Its idiomatic translation is:

My country, my native land

The people living united and progressive

May God bestow His blessings and happiness

May our Ruler have a successful reign

May God bestow His blessings and happiness

May our Ruler have a successful reign.

The tune of Malaysia’s national anthem, “Negaraku,” originated from the popular song “Terang Bulan,” which was adopted as the Perak state anthem in the late 19th or early 20th century. Accounts differ, but the melody was reportedly played in England during royal ceremonies when Perak rulers visited, despite the state not officially having an anthem at the time. The song itself may have been influenced by a French composition and gained popularity in Southeast Asia before being used at social events and official functions.

As Malaya prepared for independence in the 1950s, a committee sought a national anthem through an international competition but found none suitable. It ultimately selected the Perak state anthem’s melody, with new lyrics prepared by a panel that included Tunku Abdul Rahman. The song later became the national anthem of independent Malaya and, subsequently, Malaysia.alaysian flag from his baseball cap.

Constitution of Malaysia

The Constitution of Malaysia was adopted on Malaysia’s Independence Day on August 31, 1957 and was promulgated in 1963 when Sabah and Sarawak joined the Federation of Malaya to form Malaysia. Derives from the former Federation of Malaya, with provisions for the special interests of Sabah and Sarawak, the constitution prohibits discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, descent, sex and place of birth. It provides for the election of a head of state, the yang di-pertuan agong (king) for a single term of five years by the Conference of Rulers. The constitution also provides for a deputy head of state, chosen in the same manner and for the same term. The Malaysian constitution has been amended many times. [Source: Malaysian Government; Diane K. Mau, Governments of the World: A Global Guide to Citizens' Rights and Responsibilities, Thomson Gale, 2006]

Government in Malaysia is based largely on the Malayan Constitution of 1957, along with the amendments enacted with the formation of Malaysia in 1963. The Federal Constitution of Malaysia is the supreme law of the nation that distributes the power of governance in accordance with the practice of Parliamentary Democracy. Although Malaysia's political system was modeled after Britain, where parliament is supreme, the constitution of Malaysia established a modified separation of powers where certain powers, including judicial review, were allocated to the courts. The Constitution may be amended by a two-third majority in Parliament.

In Malaysia, human rights are partly protected under the Federal Constitution. The document guarantees several fundamental liberties, including the right to life, freedom of movement, freedom of speech, assembly and association, freedom of religion, and rights related to education. Most provisions of the constitution can be amended with the approval of at least two-thirds of the members of each house of Parliament. However, certain “entrenched” clauses — such as those relating to the powers of the Malay rulers — require the additional consent of the Conference of Rulers. Because the same dominant political coalition governed Malaysia from before independence for many decades and consistently held the necessary parliamentary majority, constitutional amendments have been relatively easy to pass. As a result, Malaysia has one of the most frequently amended constitutions in the world.

The constitution also contains two distinctive features shaped by the country’s history. First, at independence it was decided that Malaysia would have a single national monarch rather than only the nine hereditary Malay rulers of the states. The rulers form the Conference of Rulers and elect one among themselves to serve as king, or Yang di-Pertuan Agong, for a five-year term. The position rotates among the rulers.

Second, the constitution includes explicit provisions safeguarding Malay rights and privileges, reflecting policies that originated during the colonial era. These articles protect the status of the Malay language as the national language, recognize Islam, uphold the position of the rulers, and reserve certain opportunities for Malays, including a share of civil service positions, selected occupations, scholarships, and land reservations. These protections were part of a political compromise with non-Malay communities in exchange for the granting of citizenship based on birth (jus soli).

History of the Constitution of Malaysia

The drafting of the Constitution of the Federation of Malaya was the first step toward the formation of a new government after Britain agreed to concede independence to Malaya in 1956. For the task of drafting the Constitution, the British Government formed a Working Committee comprising representatives from their side, advisors from the Conference of Rulers and Malayan political leaders. [Source: Malaysian Government]

Following the Alliance’s landslide victory in the first Federal Election in 1955, Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra was appointed Chief Minister. In January 1956 the Tunku headed a delegation to London to discuss the Federal Constitution and negotiate the date for independence of Malaya. In March 1956 a Commission chaired by Lord Reid was set up to formulate a draft and refine the Constitution of the Federation of Malaya. The Commission sought the views of political parties, non-political organisations and individuals on the form of government and racial structure appropriate for this country. In the consultation process, a memorandum from the Alliance had gained precedence.

The memorandum, an inter-communal conciliation aimed at mutual interests and strengthening the nation's democratic system of government, took into account five main factors namely the position of the Malay Rulers, Islam as the official religion of the Federation, position of the Malay language, the special rights of the Malays and equal citizenship.

The draft drawn up by the Reid Commission was authorised by the Working Committee as the Constitution of the Federation of Malaya commencing on the date of the nation’s independence on August 31, 1957. When Sabah and Sarawak joined Malaya in 1963, several provisions in the Constitution were amended and the country’s name was changed to Malaysia.

Capitals of Malaysia

Kuala Lumpur is the national capital of Malaysia and the country’s largest city. Putrajaya, about 25 kilometers south of Kuala Lumpur, is Malaysia’s federal administrative capital and the seat of the executive branch. Parliament meets in Kuala Lumpur. Both Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya are federal territories. Kuala Lumpur remains the official national capital and legislative seat, while Putrajaya serves as the primary centre for federal administration and judicial functions.

Kuala Lumpur serves as the financial, economic, and cultural centre and remains the constitutional capital. Kuala Lumpur is also the seat of the legislative branch, housing the Malaysian Parliament, and it contains the official residence of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, the constitutional monarch and Indonesia king. Although many administrative functions have been relocated, the city continues to play a central role in national governance.

The Malaysian Houses of Parliament (Malay: Bangunan Parlimen Malaysia) is the complex where Parliament meets. Located near the Perdana Botanical Gardens and close to the National Monument, the complex consists of a three-story main building and a 17-story tower rising about 77 meters. The main building contains the Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) and the Dewan Negara (Senate), while the tower houses offices for members of Parliament.

Putrajaya was developed in the 1990s to ease congestion in Kuala Lumpur. The city now accommodates most federal ministries and government agencies. It also serves as the judicial centre, with major courts located there. Since 1999, Putrajaya has effectively functioned as the seat of the Malaysian government.

A key landmark in Putrajaya is Perdana Putra, the building that houses the Prime Minister’s Office and much of the Prime Minister’s Department. Situated on the city’s main hill, it is closely associated with the executive branch of the federal government. Construction began in 1997 and was completed in early 1999, with government offices moving from Kuala Lumpur soon afterward. The former prime ministerial office on Jalan Dato Onn in Kuala Lumpur has since been converted into the Memorial Negarawan museum, which commemorates the independence of Malaya, Sabah, and Sarawak.

Putrajaya was named after Malaysia’s first Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra. Planned as a modern “garden city,” it covers roughly 4,931 hectares and lies within the Southern Growth Corridor, part of the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC). Today, Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya function together as federal territories — the former as the constitutional and legislative capital, and the latter as the administrative and judicial centre of government.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026