INDIANS IN MALAYSIA

Malaysian Indians are the smallest of three main ethnic groups in Malaysia after Malays and Chinese. Malaysian Indians form about seven percent of the population. Most are descendants of Tamil-speaking South Indian immigrants who came to the country during the British colonial rule. Lured by the prospect of breaking out of the Indian caste system, they came to Malaysia to build a better life. There are smallers numbers of Malayalees, Punjabis, Gujaratis and Sindhis. Predominantly Hindus, Malaysian Indians brought with them their colorful culture such as ornate temples, spicy cuisine and exquisite sarees. The main Indian language’s spoken in Indonesia are Tamil, Malayalam, Punjabi, Gujarati, Sindhi, English [Source: Malaysian Government Tourism]

There are about 2.2 million people of Indian decent (excluding those of Pakistani and Bangladeshi descent) in Malaysia. Although they originally came from many parts of South Asia and include Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, Christians and Parsis. Most are Tamils. they are generally categorized as two types; 1) “Bengalis,” or north Indians; or 2) “Klings,” or Tamils and south Indians, . There are significant numbers of Telugus, Pathans, Malayalis, Punjabis and Sikhs. Collectively, there are about 150,000 members of these groups.

Ethnic Indians occupy the bottom of Malaysia's economic and political hierarchy. There have been tensions between them and conservative Muslims. Vijay Joshi of Associated Press wrote: “At the time of independence, most Malaysians were poor, regardless of race. But an affirmative action program that gives Malays preference in university admission and government jobs, discounted homes and a mandatory 30 percent share of all publicly listed companies has lifted the Malay standard of living. The Chinese, already well established in business, continued to flourish. But the Indians remain at the bottom of the barrel. [Source: Vijay Joshi, Associated Press, March 6, 2008]

As in Singapore, the term “Indian” is something of a misnomer as it includes a large number of different ethnic and religious groups whose main point in common is their origin in the Indian subcontinent. Most ‘Indians’ live in peninsular Malaysia and around 80 percent are Tamils. Indian Muslims have a high rate of intermarriage with the Malay community. [Source: Minority Rights.org, January 2018]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MALAYSIA: HARMONY, DISHARMONY, GOVERNMENT POLICIES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA: DISCRIMINATION, SEPARATION, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

CHINESE IN MALAYSIA: HISTORY, GROUPS, BUSINESS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

ORANG ASLI: GROUPS, HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHY LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com

SEMANG (NEGRITOS OF MALAYSIA): LIFE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

SENOI: HISTORY, GROUPS, DREAM THEORY factsanddetails.com

TEMIAR: HISTORY, SOCIETY AND RICH RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

History of Indians in Malaysia

There has been an Indian presence in Malaysia for over a thousand years. Tamils and others from the Indian subcontinent introduced Hinduism and Islam, as well as their respective cultures, to Malaysia. Evidence of "Indianized" kingdoms in the area dates back 1,500 years, but large-scale Indian immigration did not occur until the development of the plantation economy under British rule in the 19th and 20th twentieth centuries. Many of these new arrivals were indentured laborers from Tamil Nadu and other parts of India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, who were brought to work on rubber plantations. Some came as traders and miners.

Due to its proximity of southern India to Malaya, the largest groups of Indian migrants until the mid-1900s were from southern India, particularly the Tamil, Telugu, and Malayalam minorities. Others were brought in for specific economic purposes, such as building and maintaining railways. They have tended to be economically disadvantaged in Malaysia, as many worked as laborers on plantations with little or no access to quality education.

The main group of Indian immigrants in Malaysia and Singapore are Tamils. Many were brought in by the British from South India and to a lesser extent Sri Lanka during the 20th century to work as laborers in the tin mines and at rubber, palm and tea plantations. Most Indians in Malaysia speak Tamil and English.

Before independence many Indians were employed in rubber plantations, though some occupied other labour force categories: the Punjabis for example tended to work in the police force. Their economic situation has tended to deteriorate since independence in 1957 and the closure of many rubber plantations, since they are excluded from the Bumiputera (pro-Malay) policies and have not succeeded as well as the Chinese in economic and educational terms.

By the early twentieth century, Indians were estimated to represent up to 15 percent of the population of what is now Malaysia. Demographically speaking, this was the high point for the Indian minority; many left or did not take up Malayan citizenship after independence in 1957. The outward flow of Indians increased further after the May 1969 race riots. Though the Chinese were the main targets, members of the Indian minority were also among the victims because they had supported opposition parties associated with ethnic Chinese. Following the departure of tens of thousands of Indians, their proportion of the Malaysian population had fallen considerably by the 1990s.

Indians have tended to live in the cities. They have worked as small business owners, civil servants or in professions such as law and medicine. Some still work as laborers. time. In the early 1970s, 60 percent of Indians still lived and worked on plantations often under harsh conditions. Many are still there.

Indian Plantation Workers in Malaysia

Many Indians are employed in menial jobs, such as rubber and oil plantation work. Associated Press reported in 2008 about 85 percent of ethnic Indians are descendants of indentured laborers brought by the British to work on rubber plantations in the 19th century. The work, where it remains, pays about $60 per month. However, many plantations were converted into golf courses and luxury residential communities in the 1980s and 1990s, causing the workers to lose their jobs, as well as the free housing and schooling that came with them. [Source: Vijay Joshi, Associated Press, March 6, 2008]

Other plantations were converted to palm oil, which did not require the skills of rubber tapping, and Indian workers were replaced by Indonesian immigrants willing to work for lower wages. Another rubber estate in Kuala Lumpur was cleared to make way for stadiums and athlete housing for the 1998 Commonwealth Games.

Former workers continued to live on the remaining 40-acre plot, which was slated to become a graveyard. The residents were classified as squatters and were offered two-room rental apartments in a nearby low-cost housing development. Their school and temple were to be relocated inside the burial ground, a proposal that angered the residents. "My age is 43 years. I have lived here for 43 years. How can I be a squatter?" Shanti Vasupillai told Associated Press. "All I am asking for is our rights."

Issues Among Indian Malaysians

According to Minority Rights.org: Indians continue to be disadvantaged economically as they are not Bumiputera and do not have the demographic weight to be able to exercise any large degree of political power. They continue to face significant poverty and relatively low levels of education as compared to the Chinese, without being able to benefit from any of the affirmative action programmes restricted to Bumiputeras. [Source: Minority Rights.org, January 2018]

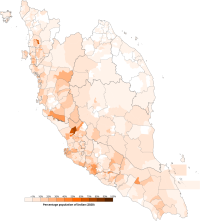

Percentage population of Indians in different parts of Peninsular Malaysia, according to 2020 census; there are hardly any Indians in Malaysian Borneo

As with the Chinese community, Indians have also expressed disquiet at the government’s language policies, such as the exclusive use of Malay, which creates a tangible barrier for employment in the civil service, and the refusal to allow Tamil to be used as a language of service, as well as the continuing refusal to teach in Tamil in public schools, despite the 2003 announcement that Tamil could be taught as an elective in some state schools. Education in Tamil usually occurs in private schools which in 2006 were still not fully funded by the Malaysian government.

There are also concerns that statements by UMNO (United Malays National Organization) leaders during its 2006 Annual General Meeting signalled an increasingly pro-Muslim and Malay agenda resulting in further restrictions on the religious and cultural practices of the Indian minority.

In September 2007, a lawsuit was filed in London by Malaysian lawyers backed by the Hindu Rights Action Force (HINDRAF). The suit, on behalf of Malaysia’s 2 million ethnic Indians, is against the current British government and demands that the court hold the British colonial authority liable for shipping millions of Tamil-speaking South Indians to Malaya and later abandoning them without adequate safeguards for their position, rights and future. The lawyers were calling for £1 million in compensation for every minority Indian in Malaysia for their ‘pain, suffering, humiliation, discrimination and continuous colonization’, and wanted the court to declare Malaysia a secular state and not an Islamic one.

In November 2007 the ethnic Indian community staged its biggest ever anti-government street protest in Kuala Lumpur when more than 10,000 protesters faced riot police to voice complaints of racial discrimination. Ethnic Indians claim that the government affirmative-action policy in favour of majority ethnic Malays has marginalised them and the protest was politically significant ahead of the coming elections. See Below

Discrimination Against Indians in Malaysia

Many Indians allege they are deprived of employment and education opportunities and say their temples are being systematically destroyed. They have laso spoken out strongly against the government’s decades-old affirmative action policy favoring Malays in education, jobs and business. Authorities deny any unfair discrimination, saying minorities in need also receive assistance.

While Malays control the government and the Chinese dominate business, Indians complain they are at the bottom of the society with little wealth, education or job opportunities because of government policies that give preferential treatment to Malays. Many Indian still do menial labor similar in nature to what the British brought them to Malaysia to do.

Reporting from Rinching, about 50 kilometers from Kuala Lumpur, Vijay Joshi of Associated Press wrote: “With a small knife, plantation worker Ramalingam Tirumalai makes raw incisions on the rubber trees every morning to harvest the oozing gooey latex. Just like the gashes on the trees, Ramalingam says, countless wounds have been inflicted by Malaysia's government on the country's ethnic Indian minority, denying them jobs, education, freedom of religion and most of all dignity. [Source: Vijay Joshi, Associated Press, March 6, 2008 |+|]

“The government denies discriminating against Indians, citing statistics that show the poverty rate among Malays is higher than for Indians. But analysts say the statistics are skewed because the Malay figure includes indigenous tribes that are extremely poor and not ethnically Malay. Indians were also infuriated when municipal authorities destroyed several Indian temples in 2007 because they were deemed to have been built illegally.” |+|

Ethnic Indians say discrimination continued after Malaysia's independence in 1957 because of an affirmative action policy favoring Malays. Activists say more than two-thirds of ethnic Indians, who constitute about 8 percent of the population, live in poverty, with many trapped in a cycle of alcoholism and crime.

Bad Feeling Stirred Up When Muslim and Hindu Festivals in Malaysia Coincide

In October 2006, Malaysia's prime minister defended joint religious celebrations by the country's Muslims and Hindus. "A joint celebration does not mean that Muslims and Hindus have to mix their religions. "Everyone has their own beliefs and faith,'' Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi said in a speech. "It does not in any way tarnish one's religion.'' The comments were apparently aimed at ending a controversy over whether Muslims should send holiday greetings to Hindus for their religious celebrations including the festival of lights, Diwali or Deepawali. [Source: AP, October 18, 2006]

Associated Press reported: Diwali was followed by Eid-al-Fitr - known in Malaysia as "Hari Raya'' - the main Muslim holiday at the end of the fasting month of Ramadan. The two lunar calendar holidays often occur back to back and are celebrated together in a weeklong holiday, nicknamed "Deeparaya.'' Controversy erupted this year after the religious chief of a government-linked Islamic finance group, Takaful Malaysia, advised its Muslim employees not to wish Hindus "Happy Diwali.'' In an e-mail to employees, Mohamed Fauzi Mustaffa described Hindu festivals as being against Islamic tenets because they involve idol worship, considered blasphemous in Islam.

Takaful Malaysia, which is majority-owned by Malaysia's Bank Islam, later apologised after Hindu groups, many Muslims and government ministers expressed outrage at the comments, describing them as a narrow interpretation of Islam. "The issue at hand is about ... creating a sense of unity among all the races in the country and one identity that we are all Malaysians,'' said Abdullah, a respected Islamic scholar. "I do not want any confusion in all this ... I want to set the record straight that this does not in any way go against the faith of Muslims in the country,'' Abdullah said.

Anti-Hindu 'Cow Head' Demonstration and the Caste System in Textbooks

In August 2009, a religious dispute in Malaysia escalated when a group of Muslim protesters used a severed cow’s head to protest the relocation of a Hindu temple into a Muslim-majority neighborhood in Selangor state. According to media reports, about 50 protesters brought the cow’s head—an animal sacred to Hindus—to a state government office and trampled on it. Photographs of the bloodied head were widely circulated online, intensifying public outrage. [Source: AFP, August 29, 2009]

The incident drew sharp criticism from political leaders across party lines. Khairy Jamaluddin, head of the youth wing of the ruling United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), condemned the protest as emotionally driven and deeply offensive, warning that it disregarded religious sensitivities and threatened social harmony. Opposition leader Lim Kit Siang described the act as deplorable, arguing that in a multi-religious society, insulting one faith amounted to insulting the entire nation.

Police said the protesters would be investigated for possible sedition. However, the demonstration’s organizer denied responsibility, refused to apologize, and said the act reflected local anger over the temple’s relocation rather than an organized attempt to provoke Hindus.

Tensions resurfaced in January 2011, when ethnic Indian groups criticized the government for retaining a high school literature textbook that referenced the Hindu caste system. Activists argued that the material was insensitive and portrayed ethnic Indians as inferior. While the government said amendments would be considered, Hindu organizations called for the book’s complete withdrawal, saying the issue reflected a broader failure to respect minority religious and cultural sensitivities. [Source: AP, January 28, 2011]

Indians and Politics in Malaysia

Indians have traditionally voted for the Malaysian Indian Congress, their party in the National Front. The National Front is dominated by the party of the Muslim Malay majority. It also has the support of some ethnic Chinese, who are 25 percent of the population, and some Indians, who are eight percent.

On the eve of election in March 2008, Vijay Joshi of Associated Press wrote: “Seething anger among ethnic Indians like Ramalingam is likely to singe the government during parliamentary elections on March 8. "We have been independent for 50 years," the stocky 53-year-old said of his country. "But there has been no change in the lives of Indians." Voters are upset by rising prices and a surge in urban crime. Ethnic tensions are also at a high, largely because of the increasing influence of Islam in daily life. "We need a new kind of leadership," Ramalingam said in an interview near his plantation. [Source: Vijay Joshi, Associated Press, March 6, 2008]

But now the Indians will "definitely vote for the opposition," said S. Nagarajan of the Education, Welfare and Research Foundation, a nonprofit group that represents impoverished ethnic Indians. "This time there is raw anger." Indian voters could make a difference in 62 of the 222 constituencies, said Denison Jayasooriya, a political analyst who specializes in Indian affairs.

Protests by Indians in Malaysia in the 2000s

In March 2001, six people, including five Indians, were killed and 50 people were injured in clashes between Indians and Malays that broke out in a poor area of Kuala Lumpur. Most of the wounded were ethnic Indians. When opposition leaders claimed that the casualty figures were higher, the government threatened to charge them with sedition. However, no charges were ever brought.A group of Indians sued the government for not doing enough to stop the fighting. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The disenchantment of Indian Malaysians exploded in November 2007 when 10,000 to 20,000 Indians demonstrated in Kuala Lumpur. The protest was seen as a watershed in the country's politics, emboldening Malaysians unhappy with the government and boosting opposition parties to spectacular gains in general elections in March. Several smaller demonstrations have taken place since. [Source: Associated Press, October 16 2008]

In 2007, Indians demonstrated in Kuala Lumpur over privileges granted ethnic Malays and discrimination against Indians. The protesters — some of whom carried pictures of India's independence leader Mohandas Gandhi and banners that read "We want our rights" — gathered before dawn near the Petronas towers. Tear gas and water cannons were needed to put the protests down. The protests were organized by the Hindu Rights Action Force, or Hindraf. [Source: Associated Press, November 26, 2007]

Associated Press reported: “Slogan-shouting protesters hurled water bottles and stones at police, who chased them through streets surrounding the famous Petronas Twin Towers and doused them repeatedly with tear gas and chemical-laced water for more than eight hours. There were no immediate reports of injuries. Witnesses saw people being beaten and dragged into trucks by police. Shoes and broken flower pots littered the scene after protesters scattered to hide in hotels and shops. The organizers said hundreds of people were detained by the time the protest dispersed. "This gathering is unprecedented," said protest leader P. Uthayakumar. "This is a community that can no longer tolerate discrimination." It was the second such street protest in Kuala Lumpur in month. A November 10 rally that drew thousands of people demanding electoral reforms was also broken up with similar force, but lasted only a few hours.

The protest—the largest involving ethnic Indians in at least a decade—was linked to a major lawsuit filed in London seeking compensation for the historical exploitation of Indian laborers under British rule. Government officials condemned the rally as politically motivated, while police justified the crackdown as necessary to maintain public order. Malaysian police used tear gas and water cannons to break up a banned rally. Protesters clashed with police near the Petronas Twin Towers for more than eight hours. Hundreds were reportedly detained, though no injuries were officially confirmed.

In February 2008, Malaysian police used tear gas and water cannons again to disperse an illegal rally by ethnic Indians demanding equal rights ahead of national elections. In August 2009, ethnic Indian Malaysians protested the planned demolition of Buah Pala Village in Penang, a 150-year-old settlement with deep cultural significance. The protest targeted a development plan approved by a previous government, which the new opposition-led state administration said it could not legally reverse.[Source: Associated Press, February 15, 2008; August 3 2009]

Arrests and Crackdowns After the November 2007 Rally

The November 2007 protests were organized by the Hindu Rights Action Force (Hindraf). In December 2007, five of its top leaders were detained under Malaysia’s Internal Security Act (ISA), which allows indefinite detention without trial. Hindraf chairman P. Waytha Moorthy fled abroad and lived in exile in London. Authorities also charged dozens of Indian demonstrators with serious offenses, including attempted murder, and denied them bail. [Source: AP, May 8, 2009]

In October 2008, the government formally banned Hindraf, labeling it an extremist group that threatened public order and racial harmony. The ban made participation in Hindraf activities a criminal offense. Hindraf leaders rejected the accusations, saying they were demanding equal rights for marginalized Malaysian Indians and accused the government of suppressing dissent. [Source: Associated Press, October 16 2008]

In May 2009, the government released 13 detainees held under the ISA, including three Hindraf activists imprisoned since 2007. Despite the ban, tensions continued. In March 2011, eleven ethnic Indian activists were charged with being Hindraf members, facing prison terms if convicted. Activists argued that these actions were attempts to silence a human rights movement rather than genuine security measures. [Source: Associated Press, March 2, 2011]

Protests by Indians Raise Questions About Malaysia’s Ethnic Policies

The 2007 protests unsettled Malaysia’s government and raised fears of renewed racial tensions among Malays, Chinese, and Indians. The demonstrations were significant because they openly challenged both a ban on public rallies and Malaysia’s long-standing policy of preferential treatment for the Malay Muslim majority. [Source: John Burton, Financial Times, January 9, 2008]

The government reacted strongly. Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi used the Internal Security Act to detain five Indian protest leaders without trial and considered restricting migrant workers from India. The protests exposed deep grievances in a country often viewed as a model of peaceful multi-ethnic coexistence and economic openness.

Observers were especially surprised because ethnic Indians—Malaysia’s smallest and traditionally most loyal minority—led the protests. Growing discontent stemmed from issues such as the demolition of Hindu temples and legal rulings limiting religious conversion. While the protests reflected Abdullah’s earlier push for greater openness, critics suggest the harsh response was aimed at reassuring powerful figures within the ruling party who feared challenges to their authority and potential ethnic backlash.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026