KOUPREY

Kouprey (Bos sauveli) are also known as the forest ox and grey ox. First first scientifically described in 1937 and last seen in 1969, they were forest-dwelling wild bovine native to Southeast Asia that are now believed to be extinct. The name kouprey means means "forest ox" in the Khmer language. The kouprey is listed as Critically Endangered and possibly extinct on the IUCN Red List.

Kouprey once ranged from Cambodia to the Dongrak Mountains of eastern Thailand, southern Laos, and western Vietnam. There is fossil evidence that kouprey once resided in central China. It is is possible that a few individuals survive in the wilderness in eastern Cambodia.[Source: Jill Winker, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

In 1964, Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia declared the kouprey to be the national animal of Cambodia. Since then a number of search parties have been formed to look for the animal but nearly all came back empty handed except for horns from dead animals found in markets. Occasionally there are reports of sightings by locals.

Kouprey were found in open forest and savannas, often near thick monsoon forests. Their lifespan was around 20 years. They were described by Achille Urbain in 1937 based on an adult individual that was caught in northern Cambodia and was kept at the Paris Zoological Park. The first captive kouprey was caught by mistake and died of during World War II of starvation.

See Separate Article: WILD CATTLE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

Kouprey Characteristics and Diet

Kouprey ranged in weight from 680 to 910 kilograms (1500 to 2004 pounds) and had a head and body length of 210 to 223 centimeters (82.7 to 87.8 inches). Adult kouprey stood 170 to 190 centimeters (67 to 75 inches) at the shoulder. The tail was up to 100 centimeters (39.4 inches) long. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Males and females have different shapes. Ornamentation is different. [Source: Jill Winker, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

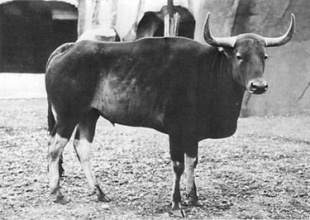

Kouprey looked a bit like a cow. Bulls were black or dark brown and had a pednulous dewlap ((skin fold that hangs from the neck) and L-shaped horns that split at the tips after three years growth. Females were paler in color. Both sexes had pale undersides and off-white legs. Kouprey young were reddish in color, but become more gray by five to six months of age. Young also had lighter colored legs.

The dewlap of the bulls distinguished kouprey from other species of wild cattle. The horns of males could reach up to 80 centimeters (31.5 inches) in length. Female kouprey also had horns, which were about half the length of male's horns, but spiraled upwards. Both males and females had notched nostrils.

Kouprey were herbivores (primarily eat plants or plants parts), and were also classified as folivores (eat mainly leaves). Among the plant foods they ate leaves, roots and tubers. They grazed on grasses, including bamboo (Arundinella species), ploong (Arundinella setosa) and koom (Chloris species). They frequented salt licks and water holes.

Kouprey Behavior

Kouprey were terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). They sensed and communicated with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. [Source: Jill Winker, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Kouprey are thought to have formed small, loose herds. They adapted a nocturnal apparently as a means of avoiding humans and retreated to the forest to escape the hot sun, emerge into the fields in the evening to feed. Female led herds, which included bulls during the dry season, reached twenty individuals.

Kouprey were are described as active and restless. They dug in the ground and thrusted into tree stumps, which caused the fraying of the male horns. They were more alert when compared to banteng and ran more gracefully. Kouprey were seen mixing with banteng and water buffalo. They roamed up to 15 kilometers per night while grazing. Herds separated and rejoined frequently.

Kouprey Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

There is little information available on mating systems in kouprey. Sexual Dimorphism suggested some level of polygyny (males mating with multiple females). In other bovids, males often compete for females and successful males are polygynous. Female left the herd to give birth, and returned about a month after giving birth to a single young. Their gestation period was eight to nine months. [Source: Jill Winker, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Kouprey mated in the spring and calved in the winter (typically December or January). Female kouprey were known for having low fertility rates. There is little data on the parental involvement of kouprey. As in other mammals, the female provides the bulk of parental care, producing milk for the young, grooming it, and protecting it from danger.

Parental care by males had not been observed. Pre-birth and pre-weaning provisioning and protecting was done by females. Pre-independence protection was provided by females. /=\

Kouprey, Humans and Conservation

Kouprey have not officially been declared extinct. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Critically Endangered. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. /=\

Recent survey efforts have been unsuccessful finding live kouprey, although some horns have been found in markets. Primary threats have been hunting, poaching and habitat loss. High levels of hunting since the 1960s resulted in at least an 80 percent decline in population numbers.

With the fall of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia in the 1980s, demand for bushmeat and trophies surged, resulting in intense pressure on all large mammals in the region. If any kouprey remain, they are likely to be in eastern Cambodia, where there are some protected areas. There are no individuals in captivity

In the past kouprey may have been preyed upon by tigers an leopards. They are thought have been very genetically diverse and immune to certain pests that plague domestic cattle in this region. Cross-breeding between kouprey and domestic cattle could potentially reduce disease. Kouprey horns and gall bladders were used in traditional medicine. /=\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2025