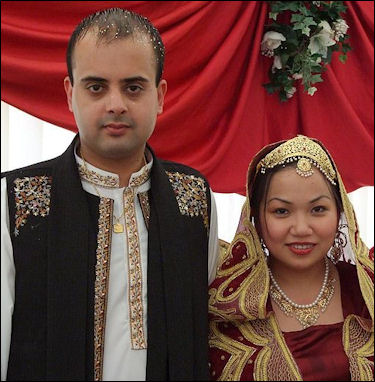

MARRIAGE IN PAKISTAN

wedding in Pakistan Age at first marriage: 26 for men and 20.3 for women (compared to 33.4 for men and 31.2 for women in Finland and 22.1 for men and 17.9 for women on Nepal) [Source: Wikipedia and Wikipedia ]

Legal Age for marriage: 18 for men and 16 for women. [Source: United Nations Data data.un.org]

Women aged 20-24 years who were first married or in union by age 18: percent (compared to 32 percent in Yemen and 3.9 percent in the United States. [Source: UNICEF data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-marriage ]

Many young men try to land jobs and save enough money to get married. In many parts of Pakistan, a wife is considered here husband's property. Traditionally, arranged marriages have been the norm and people often married a cousin or some other member of their extended family. A great efforts is made by the family to keep the marriage together.

Sunni Muslims in Pakistan follow Islamic marriage customs in which the union is formalized by nikah, a formal legal document signed by the bride and groom in front of several witnesses. A Muslim marriage is generally regarded as union not only of the husband and wife but also a union of their families. The nikah establishes that the couple is legally married. Pakistani Muslims are prohibited from marrying members of other religious. Marriages between different ethnic groups is also discouraged if not banned, In this way kin groups are and basically remain identical ethnically and culturally. [Source:“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices,” Thomson Gale, 2006; “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Marriage as a Bond Between Pakistani Families

Marriage is a means of allying two extended families; romantic attachments have little role to play. The husband and wife are primarily representatives of their respective families in a contractual arrangement, which is typically negotiated between two male heads of household. It is fundamentally the parents' responsibility to arrange marriages for their children, but older siblings may be actively involved if the parents die early or if they have been particularly successful in business or politics. The terms are worked out in detail and are noted, by law, at the local marriage registry. [Source: Peter Blood, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

Marriage is a process of acquiring new relatives or reinforcing the ties one has with others. To participate fully in society, a person must be married and have children, preferably sons, because social ties are defined by giving away daughters in marriage and receiving daughters-in-law. Marriage with one's father's brother's child is preferred, in part because property exchanged at marriage then stays within the patrilineage. *

The relationship between in-laws extends beyond the couple and well past the marriage event. Families related by marriage exchange gifts on important occasions in each others lives. If a marriage is successful, it will be followed by others between the two families. The links thus formed persist and are reinforced through the generations. The pattern of continued intermarriage coupled with the occasional marriage of nonrelatives creates a convoluted web of interlocking ties of descent and marriage. *

Dowries in Pakistan

In Pakistan, as is true throughout India, Bangladesh and South Asia, assets are moved from the bride’s family to the groom’s family. In most parts of the world it is either the other way around or there is no exchange of assets between families.

wedding party in Pakistan

Typically in accordance with Islamic law a dowry, called mehr, is paid by the groom to the bride's family. Although some families set a symbolic haq mehr of Rs32 in accordance with the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, others may demand hundreds of thousands of rupees. In Pakistan, Indian-style dowries are also common.

Fiza Farhan wrote in The Express Tribune: “Dowry is an “amount of property brought by a bride to her husband on their marriage”. No matter how much our societies have seemingly evolved, dowry or jahez is still practised in most geographical areas of Pakistan and surprisingly enough at all levels of social hierarchy. Historians trace back the tradition of dowry to the kanyadana concept along with the moral basis of stridhana in Hindu religion. The kanyadana concept entails that giving gifts is one of the ways to achieve higher spiritual and cultural recognition. Moreover, it is a way to compensate the bride in order to omit her from inheriting land or property from the family. [Source: Fiza Farhan, The Express Tribune, March 20, 2018. Farhan is an independent consultant and chairperson to Chief Minister Punjab’s Task Force on Women Empowerment]

“In a sharp contrast to this practice, Islam only has the concept of mehr in which the groom presents a gift to the bride. A short incident from the life of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) suggests that when Hazrat Ali came to visit him to express his wish to marry Hazrat Fatima, the Prophet (PBUH) asked if he possessed anything to offer as mehr. He replied that he had a horse and a saddle to which the Prophet (PBUH) advised him to keep the horse and to sell the saddle.

“Jahez cannot be traced back to any religious custom in Islam, yet it is widely practised in Pakistan from the poor households to the elitist urban families. Not only is the practice forbidden in Islam, it is banned legally too in some parts of Pakistan. The law titled, ‘the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Dowry, Bridal Gift and Marriage Functions Restriction Act of 2017,’ states that the total expenditures on marriages, including on baarats or valimas, shall not exceed Rs75,000. The law also restricts the maximum value of gifts given to the bride by her parents, family members or any other person to Rs10,000. Further, making it illegal for anyone from the groom’s family to ask or force the bride’s family for dowry. If they still do, they shall be liable to a two-month prison term and a fine of Rs300,000 or both.

“Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan are still behind in enacting a powerful law such as that of K-P. Even though the law in Punjab states that the expenditures on marriage should not exceed a ‘reasonable amount’, it does not clearly define dowry as a malpractice. A more desperate state could be found from the fact that the Sindh Assembly actually opposed the draft bill presented for banning dowry. Obviously, a great amount of criticism can be made on the implementation of the law.

“Dowry is a cult, a malpractice that has been followed by generations of our society after importing it from another religion and culture. My question then is, when a practice is prohibited in our religion, partially or fully banned by our legal system, an import from another culture or tradition.”

Status of a Woman in a Pakistani Marriage

A woman's life is difficult during the early years of marriage. A young bride has very little status in her husband s household; she is subservient to her mother-in-law and must negotiate relations with her sisters-in-law. Her situation is made easier if she has married a cousin and her mother-in-law is also her aunt. The proper performance of all the elaborate marriage ceremonies and the accompanying exchange of gifts also serve to enhance the new bride's status. Likewise, a rich dowry serves as a trousseau; the household goods, clothing, jewelry, and furniture included remain the property of the bride after she has married. [Source: Peter Blood, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

A wife gains status and power as she bears sons. Sons will bring wives for her to supervise and provide for her in her old age. Daughters are a liability, to be given away in an expensive marriage with their virginity intact. Therefore, mothers favor their sons. In later life, the relationship between a mother and her son remains intimate, in all likelihood with the mother retaining far more influence over her son than his wife has. *

Types of Marriages and Polygamy in Pakistan

Most marriages in Pakistan are traditional arranged marriages (See Below), semi-arranged marriages or love marriages. Most Pakistan children are raised with the expectation that their parents will arrange their marriages, but an increasing number of young people, especially among the college-educated, are finding their own spouses. So-called love marriages are deemed a slightly scandalous alternative to properly arranged marriages. Some young people convince their parents to "arrange" their marriages to people with whom they have fallen in love. [Source: Library of Congress]

Full-on love marriages (also known as court marriages) are rare, since theoretically they are set up with out "family consent". This kind of “free-will” arrangement challenges traditional mores and basic Islamic beliefs and "dishonours" the family, which is a terrible thing in Pakistani society. Without family consent, marriages are harshly disapproved of. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Semi-arranged marriage — where both men and women interact with one another before marriage under what could be described as arranged dating — has become more common, especially in urban areas and among educated families. Prospective couples have several “meet and greet” dates, both chaperoned and unchaperoned, allowing them to get to know each other. The process can take place occur over weeks, months or even a few years. Under these terms it is possible to have meeting with several potential marriage partners and get out of the relationship if so desired. Although such situations should be avoided. Thus the meetings may or may not result in marriage. If a couple does want to get married the potential groom has to get his family to send a proposal to the family of the potential bride. +

Marriage by telephone is allowed by Muslim law. The bride and groom both have to have a witness with them at their end of the line. In 2002, the famous Pakistani cricket player Shoaib Malik was married to his Indian girlfriend in this fashion.

Islam permits the practice of polygyny, whereby a man may have up to four wives at the same time. Under Pakistani law the husband is required to inform his existing wife or wives of his intentions to marry again. If these rules are not followed a man can end up in jail. In 2019, a Lahore man was sentenced 11 months in jail for getting married for the second time without the permission of his first wife. Shahid Hussain wrote in Samaa: “A fine of Rs250,000 has been imposed on him too. The court said that his prison sentence will be extending by four months if he fails to submit the said amount. The wife of Rashid Mahmood, a resident of Iqbal Town, said that he married another woman and didn’t ask for her permission. The case was taken up by a judicial magistrate. Mahmood was found guilty of violating Section 6(5) of the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1961. A man is required to submit written permission from his first wife if he wishes to marry another woman according to the law. If a man is found guilty of violating the man, then he may be imprisoned for a year. [Source: Shahid Hussain, Samaa, July 15, 2019]

Samaa also reported the how chaos ensued at a wedding in Gujranwala after the groom's first showed up. Mohsin Khalid wrote: “The woman tried to halt the wedding function. The man and his family made all efforts to throw her out of the hall. A groom's family member said that the first wife had gone to her mother's house after a fight with her husband three months ago. The woman said that her husband didn't give her a divorce or take her permission before getting married again. [Source: Mohsin Khalid, Samaa, April 21, 2019]

Arranged Marriages

Pakistani bride

It is estimated that at least 50 percent of all marriages in Pakistan are arranged by the bride and groom's parents. These marriages are regarded as a union of families not just wedding partners. Arrangements are generally made the parents — with little input from the prospective bride and groom until meetings are set up — using relatives and sometimes a marriage broker.

Traditionally, girls leave school in their teens for an arranged marriage set up by their family. Girls are expected to follow their families wishes of filial duty and clan honor. It is not unusual for a bride to meet her future husband for the first time on their wedding day.

Parents looking for perspective spouses for their children contact each other in various ways. Most matchmaking in Pakistan is done between families or go-betweens, which are typically a relative like an anunt. In the cities some people use classified ads in newspapers or matchmaking agencies like their counterparts in India. Often rural areas, many young people end up marrying their cousins. [Source: Associated Press]

The process often begins when families exchange photographs of their children. Investigations are sometimes conducted into the backgrounds of family members. If a match seems appropriate a meeting is arranged with the prospective couple who often have tea while their parents are present. If a couple doesn’t wish to marry parents usually respect their wishes. The parents who agree on how much of a dowry the groom should pay.

By the early 2000s, Pakistanis looking mates were posting ads on matrimonial sites like Mehndi.com and checking what was available. Young women and their mothers screened dozen of responses and pictures and choose a couple for meetings. There was also a popular television show in which men and women described what they wanted in a perfect mate and receive e-mails form viewers. Many traditionalists regarded these methods of finding a partner as sleazy.

In a typical arranged or semi-arranged marriage set up extended families work together and comes with a number of prospective mates for a girl. She picks the ones that interest her. Chaperoned meetings are set up. If the couple like each there are other chaperoned meetings, some phone calls, and gifts but no physical contact. Pakistani-American Sabaa Saleem wrote in the Washington Post: “In the end the decision will be mine. My parents would never force me to marry a particular man. But they do expect me not to dawdle. Ideally, I should have a decision after no more than five or six meetings. I am supposed to pick a husband, accept my fate and hope the marriage is successful. Our engagement would likely last a year or two, during which we would get to know each other better — and maybe even grow fond of each other...Breaking it off at that point would be possible, but that would reflect badly on me and my family. And would represent wasted time.” [Source: Sabaa Saleem, Washington Post, August 17, 2003]

Benazir Bhutto’s Arranged Marriage

Benazir Bhutto — the Prime Minister of Pakistan from 1988 to 1990 and again from 1993 to 1996 — was married to Asif Ali Zadari — President of Pakistan from 2008 to 2013 — in an arranged marriage in 1987. People was surprised by the marriage because Zadari was considered beneath her. Zadari was a polo-playing former real estate developer from a down on its luck landowning family that made most of it money from a Karachi cinema. Before the marriage some had described him as "womanizing layabout." His family reportedly pursued Benazir for two years until she finally agreed to the marriage. Bhutto later said, "I never knew what real love meant until I met Asif." She has also praised her husband for remaining at her side and enduring problems brought upon him by her political career instead of fleeing abroad. She and Asif had three young children. [Source: Claudia Dreifus, New York Times magazine, May 15, 1994]

When asked how an independent person like herself could agree an a marriage with someone she hardly knew, Bhutto told the New York Times magazine, "I ‘couldn't’ have a love match. I was under such scrutiny. If my name had been linked with a man, it would have destroyed my political career. Actually, I had reconciled myself to a life without marriage or children for the sake of my career. And then my brothers got married. I realized I didn't even have a home, that in the future I couldn't do politics when I had to ask permission from their wives as to whether I could use the dining room or the telephone."

"Once my father died. I knew the day would come when, like all feudal families, they'd lock up the daughter so that the son takes over...I couldn't rent a home because a woman living on her own can be suspected of all kinds of scandalous associations. So keeping mind that many people in Pakistan looked to me, I decided to make a personal sacrifice in what I thought would be, more or less, a loveless marriage, a marriage of convenience. The surprising part is that we are very close and that it's been a very good match."

"I feel there is someone to spoil me, to take care of me, comfort me. It's so nice to have somebody who cares about you. I was so lonely after my father died. I felt I was taking care of everybody lese. With Asif, for once, I had somebody with whom I'd lay my hair on the pillow and feel I was safe. I'd love to arrange my own children's marriages. I say that because I've been so happy."

Benazir Bhutto’s father — Zulfikar Bhutto — entered an arranged marriage in 1943, at the age of 15, with Shireen Amir Begum. Bhutto married his second wife, Nusrat Ispahani, an Iranian-Kurdish woman, in Karachi in 1951. Their first child, Benazir, was born in 1953, followed by Murtaza in 1954, Sanam in 1957 and Shahnawaz in 1958.

Defending Arranged Marriages

In the early 1990s, it was not unusual for girls to get married when they were 14 or even younger. There were cases in which young teenage girls were married off to 80-year-old great uncles as part of a blood feud settlement. This kind of marriages still occur in remote tribal areas but are condemned by the vast majority of Pakistanis.

In defense of arranged marriages, Saleem wrote in the Washington Post: “My parents are not evil people, who have kept me in a box my whole life, bent on handing me over to a man who will do the same. They’ve always treated me with love and respect....My parents have given me every opportunity for happiness. And I know that their happiness depends on fulfilling their responsibilities as good Muslim parents. They must see their children married to other Muslims of whom they approve.” [Source: Sabaa Saleem, Washington Post, August 17, 2003]

She said her religious father “believes it his duty to secure my spiritual well-being ...If he succeeds in marrying me well, ideally to a Muslim from a good Pakistanis family, then my soul will be at peace in the afterlife. Morever, he will be enabling me to follow the rules set out by Islam — to respect my parent’s wishes, to start a family and to hand down my religious morals to my children....My mother doesn’t believe she can perform the pilgrimage to Mecca...with a clear conscience until I am married.”

Dating Pakistani-Style

According to Associated Press: “Regular dating is comparatively rare, and a family’s status and wealth is usually critical for a match. A prospective bride often endures scrutiny by many suitors before finding a husband.”

Unchaperoned conversation is frowned during the arranged marriage meetings. Saleem wrote in the Washington Post, “My parents never allowed me to date and generally frowned on any male friendships. Dating leads to intimacy which would ne of the question. In high school...a tight curfew ensured my good behavior.” At a party-oriented American university she said she remains true to parents’ expectations and fending off date invitations by either pretended she was gay or saying she was busy. [Source: Sabaa Saleem, Washington Post, August 17, 2003]

An increasing number of young Pakistanis are surfng the Internet for prospective dates, Some even arrange meetings, go out on dates and get married. But if their parents find out they met over the Internet they are forced to call the whole thing off. Some people have used marriage websites to find dates rather than mates. In some cases sex meetings have been arranged over the Internet and secretly videotaped.

One man told the Los Angeles Times he met a 32-year-old woman on the Internet, When he asked her “When will you get married” She said, “Ask Allah.” He said, “When I found her trust in God, I found that she was a true girl.” He was in London at the time and asked his brother to meet with her in Pakistan and convey his marriage proposal. They were married a few weeks later.

Shaadi Online: Pakistan’s Popular Dating-Marriage TV Show

“Shaadi Online” was a popular television show in the 2000s in which young people and their parents tried to find the perfect mate, using the Internet. Associated Press reported: “Are you young? Single? Pakistani? Then “Shaadi Online” is just the Western-style dating — er, marriage — show for you. Using a combination of prime-time TV and the Internet, “Shaadi Online” has helped arrange dozens of marriages since going on air in Pakistan three years ago, shaking up a conservative Muslim culture in which family networks usually decide who weds whom. Unlike bawdy American and European shows that pair up couples for an embarrassing night out in the glare of the cameras, when the contestants choose a mate on “Shaadi Online” — which means “Marriage Online” in Urdu language — they really mean it. [Source: The Associated Press, June 7, 2006]

“Not only do viewers seem to like watching young Pakistanis choose their partner, but it offers a community service, helping men and women in what can be an agonizing search. “Shaadi Online” has also recorded shows in Dubai and London, catering to Pakistanis who struggle to find a suitable mate because they live overseas.

“Among the success stories are Sadaf Amir, 22, and her husband Amir Shaikh, 29, a pharmaceutical sales representative. He was the stand-out among a staggering 8,000 men who expressed an interest in marrying Amir after she appeared on the show. “It was great fun and much easier then the painful process of readying yourself to be shown to a new family ... and getting rejected,” Amir said in the small home she now shares with Shaikh in the southern city of Karachi. “Shaikh said he’d failed to find a wife through traditional matchmaking, “but this TV show did it for me.”

“Surprisingly, “Shaadi Online” hasn’t attracted strong resistance from the country’s formidable religious lobby, although some conservatives — if asked — object that it’s frivolous and undermines the Islamic nation’s values. “Our marriage and matchmaking has its own norms and traditions, but some television channels are implementing a certain agenda to Westernize society and harm our values,” said Merajul Huda, the leader in Karachi of Pakistan’s biggest religious party, Jamaat-e-Islami. “This program is a glaring example.”

How Shaadi Online Worked

Associated Press reported: ““Each weekly program showcases two men and one woman, introduced in a prerecorded video presentation showing their family, friends and work life. Once on the set, they are gently questioned by the hosts on their preferences for a mate. That information is fed into a computer database of 100,000 singles. They are presented with a list of possible matches to choose from, and, on the show, they phone the ones that most catch their eye, while viewers listen in. Singles who have registered with the database via the Internet can also express an interest by e-mail. [Source: The Associated Press, June 7, 2006]

“A guest married couple is also on the set to offer advice on the suitability of a proposed match — a nod to Pakistani tradition that was certainly never featured in the original dating show: Chuck Barris’ irreverent “Dating Game” on American TV in the 1960s and ‘70s. On a recent “Shaadi Online,” 20-year old Aliya Ansari, who lives the United Arab Emirates, was seen in her video walking on Dubai’s white-sand beach, saying she was looking for an open-minded, professional and tall husband who would like to live in Dubai with her.

“As fate would have it, one of the computer matchups was Muhammad Kashif, a 24-year-old banker in Dubai, who happened to be one of the two men featured on the same show — which also caters to Pakistani expats looking for a partner in their homeland. “He looks nice and impressive,” said Ansari, who was wearing an orange T-shirt and a skintight blue jeans. “She is very beautiful,” responded Kashif, casually dressed in a black shirt and light brown pants.

“Ansari’s main concern was whether her would-be husband would allow her to work as a flight attendant. The reply from Kashif: “I have no objection if she insists.” They chatted about their respective families, and the show ended with the two shaking hands and smiling, apparently ready to become lifelong partners.

“The show’s makers play down comparisons with Western dating shows.“This is not really a dating show,” said host Mustanswer Hussain Tarar, a prominent romance writer and actor. “It offers a helping hand in making a social contract with the consent of the couple and their parents.” So far, it’s matched 35 couples for marriage — although many more may have been paired through the Web site. But not every applicant seeking “Shaadi Online’s” help has been single. “I was little puzzled when a lady came with her husband to get him a second wife as they were childless after several years of marriage,” Tarar said. The couple never made it on air, although according to Islamic tradition, a man can take four wives if he can support them all.

Proposals for Marriage in Pakistan

Once a decision has been made by either the man or woman or both to get married, one or more representatives of the potential groom's family pay a visit to the potential bride's family. In traditional arranged marriages, the first visit is for the parties to become acquainted with one another and does not include a formal proposal. Following the first visit, both the man and woman have their say in whether or not they would like a follow up to this visit. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Once both parties are in agreement, a proposal party is held at the bride's home, where the groom's parents and family elders formally ask the bride's parents for her hand in marriage. In semi-arranged marriages, the first or second visit may include a formal proposal, since both the man and woman have already agreed to marriage prior — the proposal is more or less a formality. In love marriages, the man directly proposes to the woman. Once the wedding proposal is accepted, beverages and refreshments are served. Depending on individual family traditions, the bride-to-be may also be presented with gifts such as jewelry and a variety of gifts. Some religious families may also recite Surah Al-Fatihah. +

Early Stages of a Pakistani Wedding

The wedding process begins with the signing or a marriage contract (the nikah, nikanamah). It is usually signed by the parents a few days before the wedding festivities and celebrated with a mehndi ceremony that signifies the coming together of the families. The nikah formalizes the marriage. Legally no one needs to officiate at the ceremony; the couple can simply consent to be married before witnesses.

Pakistani weddings can take up to six days and often includes lots of feasting and the exchange of presents, which are often displayed for all to see. During part of the event that bride gets together with her female friends in a room and spend nearly an entire afternoon having elaborate henna tattoos drawn all over their hands. Often the designs are made on the bride by female members of the groom’s family and removed before the wedding and new ones, with elaborate floral designs on the hands and feet, are made by professional artists.

The bride’s family is often expected to provide a dowry comprised of clothing, jewelry and household electronics and appliances. Sometimes a guard is present to protect them and a announcer announces them. Among some groups in Pakistan, the groom’s family provides a bride price.

Each ethnic group has certain ceremonies that are an important part of the marriage process. According to “Countries and Their Cultures”: There are other Muslim marriage traditions as well. One includes the mayun or lagan which takes place three or four days before the marriage and starts with the bride retiring to a secluded area of her home. Wedding customs vary somewhat among provinces, but the Muslim marriage is seen as uniting both families as well as the couple. [Source:“Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Wedding in Pakistan

During the wedding ceremony the bride and groom sit like a king and queen on throne, receiving guest after guest. At some points the friends of the bride steal the groom’s shoe and the groom has to pay a ransom to get it back. Music is often played before and after the ceremony. During the ceremony itself the couple exchanges vows while a Quran is held over the bride's head. A mullah issues or shows the nikah, in the presence of the family members and guests. At least two witnesses are supposed to be present. All the guests offer a short prayer for the success of the marriage. After the ceremony, dried dates are distributed to the guests.

The bride usually wears a decorative scarf and dress along with “tikas” (a jewel worn dangling over the forehead), “damani” (jeweled headband), and “jhumat” (a cluster of chains that hang from the sides of the head). These jewels are commonly given as dowry presents from the mother to daughter. The groom usually wears a ring of followers around his neck. At some Pakistani weddings the groom wears an odd-looking hat with yellow cellophane tinsel hanging in front of it called a “naushah” .

The wedding party is hosted by the bride’ family and is often an elaborate affair held in hotel or in a tent set up near the bride or groom’s home. Foods such as “biryani” (saffron flavored rice made with lamb, nuts and a meat sauce), “karma” (vermicelli pudding), spiced rice and mutton are served on trays garnished with flowers. Men and women often eat in separate sections.

Punjabi Marriage and Weddings

Among Punjabis, arranged marriages are common and newlyweds generally live with the groom’s parents. The ceremonies vary greatly according to caste, religion and region. Generally, the family of the bride presents a gift to the family of the groom. The family of the bride pays for the wedding expenses. Gifts in the form of a dowry are given by parents to the bride. Divorce is difficult after children are born but are often inevitable if no children are born.

During grand Punjabi weddings the groom arrives on the back of white horse, wearing a turban, and sit s with his bride by a huge bonfire. A Punjabi wedding was brilliantly brought to life in the film “Monsoon Wedding”.

In Pakistani Punjab, the groom has traditionally been given a ritual bath by a barber at his home and afterward was dressed in a white satin wedding costume and a white turban with gold and floral decorations that hide his face. In the old days he traveled by horse to the bride’s home. Today he usually goes by car. When he arrives he is welcomed with firecrackers and music. While the bride is secluded, the groom signs the “nikah”, the marriage contract, in the presence of a religious scholar. Afterwards the bride’s father and the scholar go to the bride’s quarters to get her consent. After this the groom takes his wedding vows without the bride being present and passages of the Quran are read.

The following day the bride puts on a red dress adorned with jewels. She and the groom face each other with a mirror between them, their eyes cast downward. A clothe is then thrown over their eyes and the groom asks the bride to be his wife. There is then a celebration with music and dancing. At some point the bride and groom leave in a decorated car for the groom’s house where a large feast hosted by the groom’s father is held. Traditionally, the couple have moved in with groom’s family.

Pashtun Marriage

The Pashtuns (Pathans) are an ethnic group that live in western and southern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan and whose homeland is in the valleys of Hindu Kush.

Marriages tend to be arranged and couples generally go along with the wishes of their parents. The union is generally sealed with the payment of a bride price to te bride’s family, who in turn uses the money to create a dowry for the bride so the newlyweds have some financial security. Wives are sometimes bought and sold. exchange marriages are common, and involve the trade of a sister or daughter between families. [Source: Akbar S. Ahmed with Paul Titus “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Hockings, 1996]

Pashtuns have very rigid rules about marriage. Polygamy is allowed in accordance with Muslim law but most unions are monogamous and generally take place within a clan or clan subsection. Pashtuns are strongly discouraged from marrying non-Pashtuns. Although divorce is easy to obtain with Islamic law it is unusual among Pathans because it involves the loss of a bride price and the man’s honor if the wife remarries.

Marriages are often between cousins, partly so any problem can be handled within the family. Parallel cousin marriages with the a man marrying his father’s bother’s daughter is preferred. . Many women get involved in arranged marriages at 15. After marriage the couple generally moves into a separate unit within the compound of the groom’s family.

Baloch Marriage and Wedding

The Baloch, also know the Balochi, Baluch or Baluchi, are an ethnic group that live primarily in the sandy plains, deserts and barren mountains of southeast Iran, southwest Pakistan and southern Afghanistan.

Baloch marriages are generally arranged between the prospective groom and the bride’s father and are often sealed with the payment of a bride-price in livestock and cash. After marriage a woman is no longer regarded as the property of her father but is considered the property of her husband. Marriages to non-Baloch are discouraged. After marriage the couple generally lives with the husband’s family. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Hockings, 1992]

As in many parts of West Asia, Baloch say that they prefer to marry their cousins. Actually, however, marriage choices are dictated by pragmatic considerations. Residence, the complex means of access to agricultural land, and the centrality of water rights, coupled with uncertain water supply, all favor flexibility in the choice of in-laws. The plethora of land tenure arrangements tends to limit the value of marrying one's cousin, a marriage pattern that functions to keep land in the family in other parts of Pakistan. [Source: Peter Blood, Library of Congress, 1994]

Only among the coastal Baloch is marriage between cousins common; there, nearly two-thirds of married couples are first cousins.The coastal Baloch are in greater contact with non- Baloch and manifest a concomitantly greater sense of group solidarity. For them, being "unified amongst ourselves" is a particularly potent cultural ideal. Because they are Zikris, they have a limited pool of eligible mates and do not generally marry outside of the group of Zikri Baloch.

Marriages generally are monogamous and expected to be for life. Girls often get married at a very young age. It is not unusual for two cousins, one 11 and one 12, to marry a pair of brothers. Young girls were sometimes sold to suitors. Adultery has traditionally been punished by death to both parties. Polygamy is sometimes practiced. The man often lives in one house while the wives live in a separate compound together.

At a wedding party for the bride hands are painted with elaborate henna designs and women dance and place banknotes on the bride’s head. According to the Government of Balochistan: Marriages are solemnized in presence of mullah and witnesses. Life partners are commonly selected within the family (constituting all close relatives) or tribe. Except for a negligible fraction of love marriages, all marriages are arranged. A lot of marriage rituals are celebrated in different tribes. In some tribes, the takings of “Valver”, a sum of money paid by the groom to his to be wife’s family, also exist. But this custom is now gradually dying out since it has given rise to many social problems. [Source: Government Of Balochistan, balochistan.gov.pk]

Sindhi and Brahui Marriage and Wedding

Sindhis are the natives of the Sindh province, which includes Karachi, the lower part of the Indus River, the southeast coast of Pakistan and a lot of desert. Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: Marriages among Sindhis are arranged, with partners sought from within one's zat or biradari. The ideal marriage is between first cousins (i.e., a male marries his father's brother's daughter). If a suitable bride is not available, a male can marry outside his clan, even into a zat that is socially inferior to his. However, no father would allow his daughter to "marry down" into a zat of lower social standing. Betrothal of infants was common in the past, although this is no longer practiced. [Source: D. O. Lodrick “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”, Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

The marriage ceremony (nikah) is preceded by several days of festivities. The groom and his party travel to the bride's house in an elaborately decorated transport (car, donkey, or camel). The actual ceremony involves each partner being asked three times if he or she will have the other in marriage. The marriage settlements are agreed to and witnessed, and the ceremony is completed by readings from the Quran by a maulvi. (Hindus in Sindh perform their marriage ceremonies according to the Vedic rites.) Divorce is permitted by Muslim law.

The Brahui are a Dravidian language group of tribes that live mostly in Balochistan and the Sindh. Brahui men prefer to marry their brother’s daughter and polygamy is common but monogamy is the norm. Divorce is uncommon. A bride price (lab) is paid by the groom's family. Women are not necessarily veiled. Men are often armed with rifles, swords and shields.

Marriages have traditionally been arranged, with the couple’s wishes taken into consideration. In the past, child marriages were common. The practice is now banned under Pakistani law but still occurs. The various wedding and marriage ceremonies are important events for bonding families, clans and tribes. Disputes within tribes have traditionally been settled with marriages.

Marriage and Weddings Among Ethnic Groups in Northern Pakistan

The Baltis are the inhabitants of Baltistan in the area of K2 mountain in far northern Pakistan. They are interesting in that are a Muslim people of Tibetan descent. Balti wives will often marry her husband's little brother. This way a woman can stay in her home and her family and in laws remain together. The wife will often have several children by the first husband and several more by the second and everyone lives happily together under the same roof. [Source: Galen Rowell, National Geographic, October 1987 ♦]

The Bursusho, also known as Hunzakuts, are dominant ethnic group of the Hunza valley in far northern Pakistan. Burusho marriages have traditionally been held once a year: on December 21st, the winter solstice, after some snow is on the ground. Child marriage are not encouraged. Cousin marriages occur but are not common. The average marital age in the 1990s for 16 for girls and 18 for boys. Weddings are usually held at the bride’s family’s house. Marriages are technically arranged but parents generally do not insist that a couple gets married if it is against their wishes. Divorces are rare. Men are only allowed to divorce on the grounds of adultery. Women may not divorce. They can petition the Mir to force her husband to divorce her. Some polygamy occurs. There is also very little intermarriage between the Burushos and people in nearby valleys. In the neighboring Nagir valley there are very few old people over 80 and all the people in the Nagir had heard of the "superior health and longevity of the Burushos."

Divorce in Pakistan

In Pakistan, women can have only one husband even though men are allowed to have four wives. According to some interpretations of Islamic law, divorce is supposed to be easy. All a woman is supposed to do is clap her hands and say "I divorce thee" three times. But that is not the reality in Pakistan, where a man can end his marriage by doing that times but a woman must petition the court.

Statistics on divorce rates are hard to come by for Pakistan as a whole. Among urban Pakistanis forced into arranged, divorce is becoming more common. One woman told the Los Angeles Times in 2004 that she went the weddings for seven arranged marriage. Of those five ended in divorce.

In Pakistan, a father or male guardian has the right to declare the marriage of woman null and void. A case in which a father annulled a wedding certificate because his daughter eloped with her boyfriend without the father's consent was upheld in court. In many cases alimony only lasts only three months, long enough to make sure the woman isn’t pregnant.

Aisha Chowdhry of Reuters wrote: “While women divorcing their husbands is widespread in the West, growing markedly in the 20th century in many developed nations, it is a relatively new phenomenon in Pakistan. And while a divorce case in the Muslim family courts must be resolved within six months, civil divorce cases can drag on for years, making it even harder for tens of thousands of women from religious minorities to get a divorce. [Source: Aisha Chowdhry, Reuters, January 9, 2013]

There is still a stigma attached to divorce. “If deciding to ask for a divorce is painful, getting it granted is agonizing. Muslim women in the subcontinent didn’t get the legal right to ask for a divorce until the mid-1930s. Even then, a bride had to opt in by checking a box on their marriage certificate. A law passed in 1961 finally let women seek divorce through civil courts if they could show their spouses were at fault, but cases can take years.

“The public stigma, risk of violence and trauma of shepherding a case through Pakistan’s tangled justice system is so overwhelming most women never try. Sadia Jabbar, a bubbly, dimpled 29-year-old TV executive, struggled with feelings of guilt and failure after she left her cheating husband. “It was a really bad feeling, as if I had failed in the biggest decision of my life,” she said. The stigma of divorce also means women find it hard to remarry, and many feel it’s easier to stay in an unhappy marriage than be alone. The difficulties multiply when children are involved. Court-ordered child support payments to divorced mothers in Pakistan are rare and enforcement even rarer.

Among the Pashtun, the divorce rate is very low. Divorces occurs for reasons such as the inability to have children, but it is considered shameful. A widow returns to her father's home on the death of a husband, and she is allowed to remarry if it is acceptable to her family. [Source: “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, 1999]

More Pakistani Women Turn to Divorce

Reporting from Islamabad, Aisha Chowdhry of Reuters wrote: “Pakistani women are slowly turning to divorce to escape abusive and loveless marriages, once taboo and still a dangerous option in this strict Muslim nation even as more women become empowered by rising employment and awareness of their rights. But the number of women with the courage to seek divorce remains small in the face of Pakistan’s powerful religious right and growing Islamic conservatism, and in a male-dominated nation where few champion women’s rights. [Source: Aisha Chowdhry, Reuters, January 9, 2013]

“In the capital Islamabad, home to 1.7 million people, 557 couples divorced in 2011, up from 208 in 2002, the Islamabad Arbitration Council said. The Pakistani government does not track a national divorce rate. “If you are earning, the only thing you need from the guy is love and affection. If the guy is not even providing that, then you leave him,” said 26-year-old divorcee Rabia, a reporter who left a loveless arranged marriage to a cheating husband. Despite their small numbers, Rabia and other women like her are seen as a rising threat from Pakistan’s conservative forces.

“In the commercial hub Karachi, lawyer Zeeshan Sharif said he receives several divorce enquiries a week but virtually none a decade ago. Women seeking a divorce usually come from the upper and middle classes, he said. Lawyers’ fees are at least US$300, a year’s wage for many of Pakistan’s 180 million citizens. For poor housewives, hiring a lawyer is impossible. Most Pakistanis think the higher divorce rate is linked to women’s growing financial independence, a 2010 poll by The Gilani Foundation/Gallup Pakistan found. The number of women with jobs grew from 5.69 million to 12.11 million over the past decade, the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics said.

Pakistani Women Subjected Violence and Abuse Because of Divorce

There are many stories of violence and murder associated with divorce. Shafugta Bibi, a mother of two, was killed by her father, husband and uncles because she wanted a divorces. Famous Pashtun singer Ghazala Javed was killed in June, 2012. A famous beauty, she married after fleeing Taliban threats. Then she discovered her new husband already had a wife. When she asked for a divorce, she and her father were shot dead. Human rights lawyer Hina Jilani told Reuters one her clients who was seeking a divorce was shot dead in front of her by the young woman’s mother. [Source: Aisha Chowdhry, Reuters, January 9, 2013]

Aisha Chowdhry of Reuters wrote: “Women are often killed while pursuing divorces, with some shot on the way home from court or in front of their lawyers. “The women have been given so-called freedom and liberty, which causes danger to themselves,” Taliban spokesman Ihsanullah Ihsan told Reuters. “Women are also making money now and they think if they have empowerment, they do not need to sacrifice as much,” said Musfira Jamal, a senior member of the religious party Jamaat-e-Islami. “God does not like divorce ... (but) God has not given any right to any man to beat his wife or torture his family.”

“There were at least 1,636 “honor killings” last year, said Pakistani rights group The Aurat Foundation. The mere perception that a woman has behaved in a way that “dishonors” her family is sufficient to trigger an attack. [Source: Aisha Chowdhry, Reuters, January 9, 2013]

“In 2012, clerics and a religious party demanded a review of a bill to outlaw domestic violence, saying it risked undermining “family values”. Western culture, not abuse, is why women seek divorces, said Taliban spokesman Ihsanullah Ihsan.

“Yet domestic violence was one of the most common reasons for divorce, said lawyer Aliya Malik.Around 90 percent of Pakistani women experienced domestic violence at least once, a 2011 Thomson Reuters Foundation poll found. Fatima, a 31-year-old mother of two living in the eastern city of Lahore, endured seven years of severe beatings before divorcing her husband. “He used to slap me, push me, pull my hair. After I had injured my backbone very badly, he slapped me while I was pregnant,” she said. Reuters is withholding her real name for her protection.

“She got her divorce but her ex-husband refused to pay child support. Unable to get a decent job, she remarried him so he would pay their children’s school fees. Now she sleeps behind a locked door. “He will not give maintenance if I am not living in the house,” she said. “I don’t want to leave (my children) alone here. They are at a very tender age. If I could have supported them, I would have left long ago.”

Pakistan Girls Seeking Divorce and Forced to Marry Cousins

Mary Jordan wrote in the Washington Post: “Farazana Zahir, a 20-year-old woman from Lahore, said she was forced to marry her cousin — a common traditional practice — and now wants a divorce. "I strongly believe I should have choices — of whom I marry, how I spend my time," she said in an interview. After seeing a television ad placed by a local female legislator offering help to women, she called the woman's office and was put in touch with legal aid attorneys. [Source: Mary Jordan, Washington Post, August 21, 2008]

“Zahir needed a lawyer because her family told police she was "abducted" for sex by a man she met at a family party. Zahir calls the charge a sham, retribution for her asking for a divorce, something women are traditionally not supposed to demand. "If I were a boy, this wouldn't be happening," Zahir said, an olive-colored head scarf pulled over her young, determined face. "But I am going to divorce."

“As she sat in the busy Lahore law offices of Jilani and her sister, Asma Jahangir, two dozen other women waited in the corridor. Many were seeking divorces; others were fighting criminal cases they said arose from conflicts with husbands or parents. Some were older and wore black veils; most were young and wore head scarves in bright oranges, reds or floral patterns.

“Women interviewed there said men complain they are being influenced by promiscuous Western ideas. But the women say they are hardly looking for the lifestyle depicted in Hollywood movies. One young woman mentioned "Sex and the City" — available on the black market here — with obvious horror. "Why can't I talk to a boy?" asked Rashida Khan, 17, a student interviewed in Islamabad. "Why are my brothers allowed outside in the evenings and I am not? All I want is more freedom."

“Nazir Afzal, a top British legal expert on "honor" crimes in which men have killed daughters and sisters for flirting or dating, said it is not only older people who believe that women must hold to a different standard in sexual conduct. He said a young man had explained his reasoning this way: "A man is like a piece of gold and woman a piece of silk. If you drop gold into the mud you can polish it clean, but if you drop silk into mud, it's stained forever."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation (tourism.gov.pk), Official Gateway to the Government of Pakistan (pakistan.gov.pk), The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Wikipedia and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated February 2022