DANCE AND MASKED DRAMAS IN BHUTAN

There are many forms of dance and dance drama in Bhutan. Tantric practices, such as spells and symbolic mysticism, are often manifested in Bhutanese dances. All dancers are male. The masks, choreography and music are all symbolic and all are believed to have their roots in Buddhist and Bon rites. The most famous Bhutanese dancer is Padmalingpa (1450-1521), an ancestor of the present king. It is said that many of the dances he performed were celestial Buddhist dances that appeared to him in his dreams.

There are many forms of dance and dance drama in Bhutan. Tantric practices, such as spells and symbolic mysticism, are often manifested in Bhutanese dances. All dancers are male. The masks, choreography and music are all symbolic and all are believed to have their roots in Buddhist and Bon rites. The most famous Bhutanese dancer is Padmalingpa (1450-1521), an ancestor of the present king. It is said that many of the dances he performed were celestial Buddhist dances that appeared to him in his dreams.

There are three primary kinds of dances: 1) religious dances are performed by monks; 2) secular dances performed by lay people; and 3) oracle dances performed by oracles. The latter are not performed at festivals. In these, the dancers are taken over by spirits who speak through them.

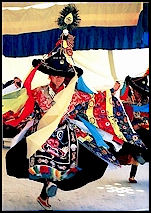

Masked dances and dance dramas are common traditional features at festivals. Energetic dancers wearing colorful wooden or composition face masks employ special costumes and music to depict a panoply of heroes, demons, death heads, animals, gods, and caricatures of common people. The dances enjoy royal patronage and preserve not only ancient folk and religious customs but also perpetuate the art of mask making.

Many dances are held at “tsechus”, sacred dance festivals, many of them honoring Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, the 8th-century saint who is credited with bringing Buddhism to Bhutan. In addition, middle school boys and girls perform dances at the king’s birthday, a national holiday. They organize their practice sessions without adult supervision. High school students practice at the sports stadium in Thimphu and spell GNH, the initials for Gross National Happiness.

Book: “International Encyclopedia of Dance”, editor Jeane Cohen, six volumes, 3,959 pages, US$1,250, Oxford University Press, New York. It took 24 years to prepare.

Religious Dances

Religious dances in Bhutan are preceded and followed by prayers that honor the spirits and deities featured in the dance. The costumes worn by the monks are generally more elaborate than those worn by lay people. They feature long brocaded robes and boots. The dances are graceful and measured and feature high stepping movements often high above the knee. Lay dancers are often barefoot and wear short colorful skirts.

Most dances are performed at festivals. In the early stage of the Tsechu in Thimphu in late September and early October, monks done masks to dispel evil spirits. Later monks, lay people perform masked and unmasked dances.

The offering of sacrifices at Bhutanese festivals is often accompanied by ritual dances and dramatic representations. Special dance sequences known as “cham” feature trained and inspired actors who impersonate gods and goblins, wearing appropriate masks and mimicking mysterious actions. They are provide a farmwork for offering the “torma,” figures made of dough and butter, shaped to symbolize deities and spirits and presented to the deities invoked. These are often called devil dances because their primary aim is drive out evil spirits — and bring good luck. [Source: Brenda Amenson-Hill, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Paul Hockings, 1992]

Character and Elements of Bhutanese Dance

Karen Greenspan wrote in Natural History magazine: “A wonderful quality of the Bhutanese people is that they do not take themselves too seriously. In the midst of the sacred cham there are always atsaras (jesters) in bright-red masks poking fun at the dancers and audience members alike. In addition to their useful function of fixing loose or crooked costumes on the dancers, they romp around performing slapstick routines, hitting up tourists for donations, and bopping people playfully over the head with large wooden phalluses. [Source: Karen Greenspan, Natural History magazine, November 2012]

“The zhey are regional expressions of praise and spiritualism identified with the coming of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, a Tibetan reincarnated lama who came to Bhutan in 1616 and is credited with unifying the country while defeating Tibetan invaders. Long songs that alternate slow and fast rhythms, they are sung and danced by men in regional costumes during their local festivals. A presentation of zhey was featured at the recent royal wedding of the popular young king. Because Bhutan is a culture that reveres and ennobles those who perform the dances, the honored bridegroom also learned a zhey to perform before the public.

“After watching Tshering Dorji demonstrate the four main zhey (each from a different region of the country), I chose to tackle Nob Zhey, which originated in the town of Trongsa. I loved how the dance starts as a slow, stately processional and then gradually transitions into a turning, jumping, twirling, and clapping tour de force. The boedras feature continuously flowing arm and hand gestures with precise finger placement.”

Festivals and Tshechus in Bhutan

There are number of annual holidays, events and festivals linked to different events in the life of Buddha. Many festivals feature symbolic dances and masked dramas, which are believed to be to bring heavenly blessings to participants and viewers. Tourists are allowed to enter the Dzong (fortified monasteries) and witness masked dramas and sword dances. Every village, town and city has its own festival. The most famous are Tshechus.

Tshechus — Bhutanese religious festivals — are held in Bhutan throughout the year. They take place outdoors, often in the courtyards of the great dzongs. People travel many miles, often on foot, to attend the festivals, wearing their most beautiful clothing, creating as festive and joyful atmosphere which mingles with the mystic spirit of the occasion. These festivals not only play an important role in preserving Bhutan’s rich culture and traditions but also provide devout Buddhists with an opportunity for prayer and pilgrimage.

Karen Greenspan wrote in Natural History magazine: “The tsechus of Bhutan are colorful spectacles melding country fair, family picnic, historical reenactments, monks’ ritual and ceremony, and collective meditation. Their main attractions are the cham, or sacred dances, many of which teach compassion for all sentient beings or reenact stories about saints and deities. Originating as much as 1,300 years ago, cham are performed by masked dancers who wear decorated silk costumes and sometimes carry and play drums, cymbals, or bells. The dancers are accompanied by monk musicians chanting and playing long horns, clarinets, cymbals, drums, and conch shells.” [Source: Karen Greenspan, Natural History magazine, November 2012]

As the Tshechu begins, villagers and visitors congregate at their local temples and monasteries were the festivals take place. Tshechus are usually occasions to mark important events in the life of Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava) — the Tantric master regarded as the second Buddha to Bhutanese. Typically, Various mask dances are performed together with songs and music for three days. These religious celebrations are lively, high-spirited affairs during which people share meals of red rice, spicy pork, ema datshi (the national dish, a stew made with chilies and yak cheese), and momos (pork dumplings) whilst downing large amounts of ara (traditional rice wine). [Source: Tourism Council of Bhutan, tourism.gov.bt]

Bhutanese Festival and Tshechu Dances

Bhutanese festivals and Tshechus often feature dancers wear colorful silk costumes and grotesque hand-carved wooden masks. The festivals celebrate the faith, legends, myths and history of the Bhutanese with ancient rituals, dance and music. The dancers — monks or highly trained laymen — take on the aspects of wrathful and compassionate deities, heroes, demons and animals. In addition to bringing blessings, the dances are performed to to instruct viewers, protect them and to abolish evil influences. [Source: John Scofield, National Geographic November 1976]

Many of the dances are centuries old and are performed once or twice a year. utrageously costumed and masked performers dance and act out ancient Himalayan tales about the reincarnation of donkeys and the struggle between good and evil. The performers twirl around in skirts that open like parachutes and dance to music produced by drums and cymbals. A fire dance performed at Bumthang is intended to help childless women attending the festival conceive in the upcoming year.

"I found the performance very difficult to follow," John Scofield wrote in National Geographic, "and curiously disquieting...Half a dozen masked jesters made fun of every motion , every symbolic act I the drama. No one among actors or audience was safe from their openly disrespectful and often obscene parodies...Bhutanese see nothing at all strange in poking fun at organized religion...jester were saying in effect, "After all, even the most serious rituals are the inventions of men, not gods."

Masks and Dancers in Bhutanese Dances

The fantastic masks used in Bhutan dances and dramas are one of the art form’s most interesting features. The masks are made of papier mache or carved pine wood, with designs and dimensions that are in accordance with ancient traditions. The wearers look out of holes in the eyes or mouth or nose. The masks are believed to be possessed by spirits before they are worn. Their color usually matches the costume. Many mask makers are monks.

The Daily Bhutan reported: “For many tourists visiting Bhutan, the flamboyant mask dances performed at a tshechu (festival) has always been a memorable highlight. It is interesting to learn that in the past, dzongkhag (district) officials usually faced numerous challenges in order to get dancers for tshechus and other functions. To address this issue, daily and monthly allowances for these folk and mask dancers were recently revised. This move has not only enticed more people to join the dancing profession, former dancers are even more motivated to stay in this line. [Source: Daily Bhutan, January 8, 2020]

“Before the revision, the monthly allowance was Nu 1,500 (US$21) for a mask or folk dancer, while the dodhams, champoens, chamjubs and tsipoens (leaders) were paid Nu 2,000 (US$28) each. However, after the wage revision, the monthly allowances for a mask or folk dancer is Nu 2,500 (US$35), while the dodhams, champoens, chamjubs and tsipoens are now paid Nu 3,000 (US$42) each. As for the mask and folk dancers, their daily allowances used to be Nu 300 (US$4) while the dodhams, champoens, chamjubs and tsipoens were paid Nu 500 (US$7). The revised daily allowances are now Nu 700 (US$9.80) and Nu 1000 (US$14) for mask or folk dancers and the dodhams, champoens, chamjubs and tsipoens respectively.

“Chukha’s dzongda, Minjur Dorji, said that compared to the past years, with the new daily and monthly allowances now, the number of dancers has increased. Moreover, the existing participants are showing an extra interest in dancing. “Until last year, the mask dancers always come up with a resignation right after a tshechu. However, we have not seen a single person coming to resign this year, and we have more than 20 mask dancers,” he added. In addition, it was difficult to get participants from gewogs (villages) in the past, even though it was mandatory to have four (two folk dancers and two mask dancers) from each gewog. “This is an encouraging initiative to preserve our culture and to keep our people engaged in cultural practices. Otherwise, it is difficult to get representatives from gewogs. Low wages was discouraging for the people,” he explained.

“A culture officer of Trashiyangtse district, Tashi Dawa, said that it was difficult to get dancers in the past, whereby they literally had to go into each gewog and request for their participation. “We circulated the post through the GUP but no one came forward, so we personally had to go and request for dancers,” he said. However, with the increase in wages for the dancers, the participants started showing extra effort and interest. On top of that, it is also getting less challenging to get the dancers from gewogs.”

“Due to the low allowances in the past, dancers usually backed out saying that the pay was too little for them to sustain their daily expenses. “They even had to pay for their own food during their practice time as their DSA was too low,” he added. Haa’s dzongda, Kinzang Dorji felt that the dancers require other motivation to be in the profession, and not just the salary. “What we need to do is, train them, make them a set of professional dancers so that they can make quite a good income apart from what the dzongkhags pay them,” he explained. “In the past, the dancers were on rotation (gewog wise), and that is why there were no dancers who were perfect. Also it was so difficult to get dancers in the dzongkhag that we literally had to hire people from other dzongkhags and drayangs sometimes.”

Different Bhutanese Dances

The Black Hat dance is performed by monks who wear full brocaded robes with wide sleeves, orange pants tucked into their boots, broad-rimmed hats and carved bone aprons depicting gods. During the dance they carry scarves in one hand and a three-sided dagger in the other. The Black hat dance is performed by most Himalayan Buddhist cultures.

The deer dance is symbolic of Padmasambhava, who while riding on a deer stopped a demon. Dancers are bear chested and wear deer masks with large antlers and costumes with a wide scalloped collar, a hat with large ear flaps, and shorts with a leopard print, covered by cloth with tiger stripe, which in turn are covered by a skirt made of four yellow scarves tied together. The dancer can see out of the mouth hole in the mask.

The dance of the Eight Manifestations features dancers in robes and masks acting out the eight manifestations of Padmasambhava, both peaceful and wrathful, and is performed to drive off negative spirits. The Pachean dance is performed barefoot by masked dancers who do high kicking jumps and acrobatic back bends to represent heros and heroines from the celestial realm.

Non sacred dances include the boedra, a court dance in which men and women dance together. Viewing them bestows blessing. The Dramnven Chotse is a dance performed by lay dancers. It celebrates a victory over forces of evil and the subjugation of spirits at a pilgrimage site by the founders of a Buddhist sect. The dancers move to rhythms created by drums, brass gongs and other percussion and melodies produce by a stringed instrument called a “dramnven”. The tshilebey is a kind of chain dance that is often performed at the end of celebrations and events. It features a couple of slow steps performed in unison by everyone who participates.

The Raksha Mangcham (Dance of the Judgement of the Dead) features a part puppet, part costumed Lord of Death and animal-masked jurors. This dramatic work tells the story of a villainous soul whose merit is weighed before rebirth. The dance is regarded as a guide to the underworld that prepares viewers of the dance for what to expect.

Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse

The Mask dance of the drums from Drametse was inscribed on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008. According to UNESCO: The mask dance of the Drametse community is a sacred dance performed during the Drametse festival in honour of Padmasambhava, a Buddhist guru. The festival, which takes place in this eastern Bhutanese village twice a year, is organized by the Ogyen Tegchok Namdroel Choeling Monastery. [Source: UNESCO]

“The dance features sixteen masked male dancers wearing colourful costumes and ten other men making up the orchestra. The dance has a calm and contemplative part that represents the peaceful deities and a rapid and athletic part where the dancers embody wrathful deities. Dancers dressed in monastic robes and wearing wooden masks with features of real and mythical animals perform a prayer dance in the soeldep cham, the main shrine, before appearing one by one in the main courtyard. The orchestra consists of cymbals, trumpets and drums, including the bang nga, a large cylindrical drum, the lag nga, a small hand-held circular flat drum and the nga chen, a drum beaten with a bent drumstick.

“The Drametse Ngacham has been performed in the same monastery for centuries. Its form has both religious and cultural significance, because it is believed to have originally been performed by the heroes and heroines of the celestial world. In the nineteenth century, versions of the Drametse Ngacham were introduced in other parts of Bhutan. For the audience, the dance is a source of spiritual empowerment and is attended by people from Drametse as well as neighbouring villages and districts to obtain blessings. Today, the dance has evolved from a local event centerd on a particular community into an art form, representing the identity of the Bhutanese nation as a whole. Although the dance is highly appreciated among all generations, the number of practitioners is dwindling due to lack of rehearsal time, the absence of a system for training and the gradual waning of interest among young people.”

Festival and Tschechu Dances

Jampa Lhakang Drub in September is annual fertility festival in the town of Jakar. The festival features clowns and dwarfs wearing masks who prance around with a wooden phallus and steal it from one another while the audience claps and children squeal with delight. During a mass fertility blessing one of the clowns drips water from a wooden phallus on the women who want to receive the blessing while each of the woman hold a stone phallus. The highlight of the festival is the fire ritual that is held in the evening where crowds gather to witness the ritualistic naked dance. A fire dance performed at Bumthang is intended to help childless women attending the festival conceive in the upcoming year.

Mask Dances or Cham are believed to confer blessings upon the spectators and teach them the ways of the Buddhist dharma are performed during the festival. Cham are also believed to provide protection from misfortune and exorcise evil influences. The festival is a religious ceremony and it is believed that you gain merit simply by attending it.

Trashigang Tshechu is held in December at Trashigang Dzong during the 7th to 11th days of the tenth month of the Bhutanese calendar. Preparations for the Tshechu begin two days prior to the actual festival. On the 7th day of the month the monks perform ceremonial ablutions or thrue. On the 8th they have rehearsals in preparation for the Tshechu. Then on the 9th of the month the Tshechu begins proper. On the 10th day the Thongdrol of Neten Chudrug (Sixteen Arhats) is unfurled amidst a flurry of mask dances.

Chung Zam Cham (Dance of the Four Garudas), performed at a tsechu in Punakha, reenacts how Guru Rinpoche changed himself into a garuda (mythical bird) to subjugate evil spirits. Guru Tshengye Cham (The Dance of the Eight Manifestaions) concludes with a procession in which an actor playing Guru Rimpoche and his entourage circumambulate the dance area. He then sits down on an elevated platform and receives blessings and sacred prayer chords from devotees. Jesters provide comic relief. A jester in a red mask represents an Indian teacher. [Source: Natural History magazine, November 2012]

The annual Wangduephodrang Tshechu in September is known for the Raksha Mangcham or the Dance of the Ox. Trongsa Tshechu at Trongsa in November is an annual festival which commemorates the life of Guru Rimpoche. The festival confers blessings, good luck and protection against misfortune for the coming year. Dancers in brilliant silk costumes and huge masks, impersonate beneficent deities, demons, spirits and heroes. This festival is regarded as one of the most authentic and least touristy in Bhutan.

Lhuntse Tshechu is usually celebrated in November and draws large numbers of people. Lhuenste is one of the easternmost districts in Bhutan and borders Tibet. Almost every village in Lhuntse has a festivals that is unique and distinct from those in other communities in Bhutan. Two notable festivals are the Cha and the Ha festivals. They are celebrated to honor the deities and avert misfortunes. The most important festival is the annual three day festival. Tshechu participants cleanse their sins by watch masked dances and also receive blessings from sacred relics that are publicly displayed.

Dance at the Thimphu Tshechu

One of the biggest festivals in the country is the Thimphu Tshechu in September. This festival is held in the capital city for three days beginning on 10th day of the 8th month of lunar calendar. This Tshechu is witnessed by thousands of people many of whom travel from neighboring Dzongkhags (districts) to attend the festivities. The actual Tshechu is preceded by days and nights of prayer and rituals to invoke the gods. To farmers, the Tshechu is also seen as a break from farm life. It’s an occasion to celebrate, receive blessings and pray for health and happiness. [Source: Tourism Council of Bhutan, tourism.gov.bt]

When it was initiated by the 4th Desi, Gyalse Tenzin Rabgay in 1867 the Tshechu consisted of only a few dances being performed strictly by monks. These were the Zhana chham and the Zhana Nga chham (Dances of the 21 Black Hats), Durdag (Dance of the Lords of the Cremation Ground), and the Tungam chham (Dance of the Terrifying Deities).

The Thimphu Tshechu underwent a change in the 1950s, when the third King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, introduced numerous Boed chhams (mask dances performed by lay monks). These additions added colour and variation to the festival without compromising its spiritual significance. Mask dances like the Guru Tshengye (Eight Manifestations of Guru), Shaw Shachi (Dance of the Stags) are enjoyed because they are similar to stage-theater. Equally important are the Atsaras, who are more than just mere clowns. The Atsaras are the dupthobs (acharyas), who provide protection. The dances and the jesting of the Atsaras are believed to entrance evil forces and prevent them from causing harm during Tshechus. Modern Atsaras also perform short skits to disseminate health and social awareness messages.

Before the three-day Tshechu, Thimphu celebrates a one day festival known as the Thimphu Dromchoe. The day long festival dates back to the 17th century. It showcases the sacred dances dedicated to the chief protective deity of Bhutan, Palden Lhamo. Legend has it, that this deity appeared before Kuenga Gyeltshen and performed the dances while he was in meditation. Based on these dances, Kuenga Gyaltshen initiated the Dromchoe.

Paro Tshechu

The Paro Tshechu (Festival) in Paro in late March and Early April is is one Bhutan's best known and most-visited dance festival. Held from the 10th to 14th day of the second lunar month on the Bhutanese calendar, it includes masked and costumed dancers who impersonate peaceful and wrathful deities and reenact legends and episodes from history of Buddhism in Bhutan. The Paro Tshechu is held in spring and is one of the most colorful and significant events in Paro Dzongkhag (district). [Source: Tourism Council of Bhutan, tourism.gov.bt]

The Tsehchu is considered a major attraction for tourists and Bhutanese who travel from neighboring districts to participate in the event. Describing a dance at the Paro Festival, Molly Moore wrote in the Washington Post, "The 'black hat' dancers swept into the medieval courtyard...in a kaleidoscope of swirling silks and exotic masks, dancing the sacred steps passed down by generations...Hundred of festively-clad Bhutanese villagers and maroon-robed monks jammed the courtyard and packed the balconies of the massive stone edifice, entranced by the dance troupes, each more exotic than the last."

“The dancers represent terrifying demons and heroic deities who reenact stories from Buddhist legend, including the Dance of the Lords of the Cremation Grounds, in which dancers wearing white skull masks and flashing long black spikes on their fingers romp through the streets as the protectors of sacred burial sites."

Raksha Mangcham (Dance of the Judgment of the Dead)

Karen Greenspan wrote in Natural History magazine: “The morning after our arrival we headed toward the outdoor grounds beside the Paro Dzong (great fortress/monastery) for the tsechu. We mingled with young kids, old folks — their teeth stained red from chewing betel-nut — grasping prayer wheels, young women carrying babies in woven wraps, men dressed in the traditional gho (a knee-length, colorfully woven belted robe) clutching their cell phones, and red-robed monks. [Source: Karen Greenspan, Natural History magazine, November 2012]

“When we arrived at the Paro Tsechu, I was delighted that we would be seeing a famous three-hour dance called Raksha Mangcham (Dance of the Judgment of the Dead). This dramatic work tells of wandering in Bardo, a dreamlike, in-between state that Buddhists believe all beings traverse after death before their next rebirth. There they are judged by the Lord of Death to determine whether they will be liberated to higher realms of existence upon their reincarnation. The Bhutanese believe that by viewing this cham, they will know what to expect upon death and won’t be frightened by the deities they will encounter.

“The dance unfolds as a courtroom drama presided over by the Raksha, an ox-masked dancer who represents the Minister of Justice. The characters include a scary-looking prosecutor, a white-masked defense attorney, a black-robed criminal, a red-robed righteous man (dressed like a Buddhist monk), a full jury of animal-masked dancers holding symbolic props (a set of scales, a mirror of fate), and an oversize costume-puppet of the Lord of Death with his attendants and angels. One of the more comical moments of the performance occurred when the villain made a run for it and escaped into the audience. All the ministers of the court ran after him and hauled him back onstage to stand trial. He was eventually convicted and dragged off on a long black cloth runner to a “lower realm.”

Tantric Cham

Karen Greenspan wrote in Natural History magazine: “Guru Rinpoche was a practitioner of a new school of Buddhism called Vajrayana or Tantra (the diamond path or thunderbolt path). Tantric Buddhism employs skillful means to accelerate progress toward enlightenment, rather than suffering through eons of endless rebirths. It developed a meditation system with complex visual, vocal, physical, and ritual supports for the practitioner. [Source: Karen Greenspan, Natural History magazine, November 2012]

“Tantric cham, passed down for generations, are rituals through which Buddhist saints are believed to have transformed themselves into deities to overcome evil forces. Some are performed, according to tradition, just as Guru Rinpoche first demonstrated them 1,300 years ago. Before performing these rituals, the monks undertake deep meditation transforming themselves into an embodiment of the deity they will represent to the public. By wearing the costume, carrying the prescribed instruments in their hands, performing mudras (sacred hand gestures), reciting mantras (sacred syllables), and by developing focused concentration, the dancers channel the deity and remain undistracted by extraneous thoughts or occurrences.

“Other cham, called Revealed Treasure Dances, are considered to have been discovered from texts that Guru Rinpoche intentionally hid all over the landscape of the Himalayas or in the minds of his disciples, in anticipation of the people’s spiritual needs in later times. Various saints and lamas have long been revered for having discovered these concealed texts, sometimes through visions or dreams. One of the most beloved and influential treasure revealers was Pema Lingpa (1450-1521), who is credited with transmitting chammasterpieces from his visions. He taught these dances to monk dancers, and also innovated the performance of cham by laypeople.

“Still other cham reflect sacred biographies. An example is the Dance of the Stag and Hounds (Shawa Shakhi Cham), a dance-drama about how the master yogi Milarepa (c. 1052-c. 1135) converted a non-Buddhist hunter into a religious man. Although the tantric dances are performed by monks, laypeople traditionally perform Revealed Treasure Dances and biography-based dances. All are deemed equally sacred in terms of generating merit for the performer and viewer. The mere viewing of these dances offers the potential for transcendence.

“One of the tantric visual aids for meditative practice is the mandala, which means “circle.” In Buddhism it is a device for leading the initiate deeper into the realization of the nature of existence through a series of concentric circles or arcs surrounding a deity. In Invoking Happiness, a colorful guide to the tsechus, Khenpo Tashi, director of the National Museum of Bhutan, says that “to be effective, and meaningful, the dance must be seen as a mandala.”

“The structure of tantric cham echoes the formal structure of a painted mandala. The dancers enter the ground of the performing arena and circumambulate clockwise, creating the form of a sacred mandala, sealing the boundaries to keep out hostile forces and empowering the circumscribed space. The positioning of the dancers in the performance space replicates the deities’ positions in a mandala diagram. And just as in the conclusion of a sand mandala ritual, in which the mandala is dismantled and the sand grains are poured into the river as a reminder of the impermanence of all things, the cham mandala dissolves. The dancers position themselves in a final mandalic floor design before exiting with a purposeful movement phrase, one by one or two by two, across the sacred space — until it is again empty.

Punakha Tshechu and Drubchen

Punakha Serdra (Golden Procession in Punakha) is held Late February, Early March during the first lunar month to commemorates the victory of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, the Bhutanese hero and founder, over Tibetan invaders in the 17th century. It features a procession depicting a 17th century war against Tibet, with galloping horsemen, silk-robed monks and swimmers who dive into the river to retrieve oranges. The Je Khenpo, the Chief Abbot of Bhutan, gives a blessing.

Located in the western part of Bhutan, Punakha is is the winter home of the Je Khenpo, the Chief Abbot of Bhutan. Punakha has been of critical importance since the time of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyel in 17th century. Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal is known as the unifier of Bhutan as a nation state and he was the one who gave Bhutan and its people the distinct cultural identity that identified Bhutan from the rest of the world. [Source: Tourism Council of Bhutan, tourism.gov.bt]

During 17th century Bhutan was invaded several times by Tibetan forces seeking to seize a very precious relic, the Ranjung Kharsapani, the self-created image of Avalokiteshvara from the first vertebra of Tsangpa Gyarey, now kept inside crystal glass. Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal led the Bhutanese to victory over the Tibetans and to commemorate the triumph he introduced the Punakha Drubchen. Since then Punakha Drubchen (also known as Puna Druchen) became the annual festival of Punakha Dzong.

The Punakha Drubchen features a dramatic recreation of the scene from the 17th century battle with Tibetan army. The ‘pazaps’ or local militia men, dress in traditional battle gear and reenact the ancient battle scene. This reenactment harkens back to the time when Bhutan didn’t have a standing army. Instead men from the eight Tshogchens — the Great Village Blocks of Thimphu — came forward and managed to expel the invading forces from the country. Their victory ushered in a period of new-found internal peace and stability.

Bhutanese Dance Lessons

Karen Greenspan wrote in Natural History magazine: ““My guide, Younten Jamtsho, took me to the Royal Academy of Performing Arts (RAPA) headquarters in the capital city of Thimphu to meet the assistant principal, Tshering, and begin the private lessons that had been arranged for me. The academy was created in 1954 by King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck (1928-1972) to provide formal training for the lay masked dances. With its mandate to preserve the traditional songs and dances of Bhutan, folk dance was added to the curriculum in 1970. The king was also responsible for the current practice of alternating folk songs with sacred dances within the tsechu programs, creating a more dynamic and entertaining atmosphere. [Source: Karen Greenspan, Natural History magazine, November 2012]

“My dance sessions were with Tshering Dorji, the nation’s folk dance choreographer. He always arrived formally attired in his gho, knee socks, and fine dress shoes. We were joined by two musician accompanists and the assistant principal. Each session was an intense four hours during which Tshering Dorji taught me the dances while singing the folk songs, the musicians played, and the assistant principal translated and made clarifications. I asked to learn a sampling from the three categories of folk songs that can be danced — zhungdra, boedra, and zhey. We danced a lovely zhungdra (classical dance) about the black-necked crane, a rare and endangered bird that features in much Bhutanese folklore. The dance is simple (only three steps repeated many times) and the tune almost hypnotic (as the melody has no rhythm).

“During our travels, while stopped at a highway roadblock, we got out of our van to stretch, and I practiced the boedra I had just learned. All of a sudden our middle-aged driver, Dawa, came running over to adjust my finger placement. His intervention pinpointed the discrepancy and corrected it. Who knew our driver was such an expert? But I eventually realized that everyone in Bhutan is a dancer — from Guru Rinpoche, to Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, the brilliant military leader; from the young king, Jigme Khesar Namgyel, to our driver, Dawa.”

Documentation of Bhutanese Dance

The Honolulu Museum of Art and the Core of Culture, a Chicago-based nonprofit dance preservation foundation, worked together to document cham dance forms for an exhibition on Bhutanese art called Dragon's Gift: The Sacred Arts of Bhutan. According to the Honolulu Museum of Art: “An extensive digital database of more than 300 hours of video documentation, including the performances of numerous rare, nearly extinct cham rituals, was created,” featuring footage of actual dances; and an installation of photographs of cham dancers by Herbert Migdall, photographer in residence for Chicago’s Joffrey Ballet. Cham is often an intimate connection between dance and arts (such as painting and sculpture) in Bhutanese rituals. After the exhibition, the museum gave one copy of the cham database to the Royal Government of Bhutan, and one copy to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, New York, the largest dance archive in the world. [Source:Honolulu Museum of Art, Dragon's Gift: The Sacred Arts of Bhutan Exhibition, February 23, 2008 — May 23, 2008]

Joseph Houseal, a choreographer and dance preservationist, recorded many of the sacred dances for Honolulu Museum of Art exhibition. Susan Emerling wrote in the New York Times: “Mr. Houseal and Gerard Houghton, a cameraman, made two early trips to Bhutan to witness the cham dances without shooting any film. Then they developed some noninvasive production techniques that would allow them “to make a clear historical record of the structure of the dance and the shape of the choreography,” Mr. Houseal said. “We never pushed it — people came to trust us, and they let us see secret things,” he said. “We revived four dances and saved one from extinction that was only known to one person in his 80s.” [Source: Susan Emerling, New York Times, February 24, 2008]

“Over two years, traveling with their gear on horses, mules and yaks, they recorded 330 folk and sacred dances performed at festivals. Typically Mr. Houghton filmed from above the brightly dressed dancers to catch the patterns of movement. On occasion he mounted a lipstick camera inside a performer’s mask to capture the swirling motion from the dancer’s perspective. “Dance is critically important to their conception of the universe,” Mr. Houghton said. “A mandala is a dance — gods dance, they don’t walk around. It is a dramatic representation of what is going on in heaven.” This understanding also informed the art-historical interpretation of the dancing figures in the thangkas and sculptures. After teaching the locals to use cameras, the team would leave behind its gear at the end of each visit, then acquire new equipment for the next round of filming.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Tourism Council of Bhutan (tourism.gov.bt), National Portal of Bhutan, the Bhutan government’s main site (gov.bt), The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Wikipedia and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated February 2022